Hiroshi Yoshida Japanese Woodcuts

RF has two exquisite Japanese woodcuts, and while she couldn’t quite make out the signature, I can. It is that of Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950), a leading artist of the Shin-hanga (“new print”) movement of the early 20th century in Japan, which focused on the techniques of traditional woodcut or watercolor, but borrowing from the Western style of landscape painting. The traditional Japanese woodblock process and images are called Ukiyo-e. First developed in the 15th century, these pieces portray landscapes and images of the theaters and brothels of the great cities. The name means images of “the floating world.” Yoshida’s art fused Eastern and Western traditions and became internationally successful.

Yoshida ‘lived’ what he sketched, travelling around the world four times on extended trips, producing remarkable woodblock prints of the Grand Canyon, the Swiss Alps, the Taj Mahal, the Alps, and famous U.S. National Parks. These were six-month tours, the rest of the year spent refining his sketches, Yoshida carving images into woodblocks for printing later. He became famous for his portrayal of mountains and images at night, described as luminous because he included a light source within the image that seemed to glow.

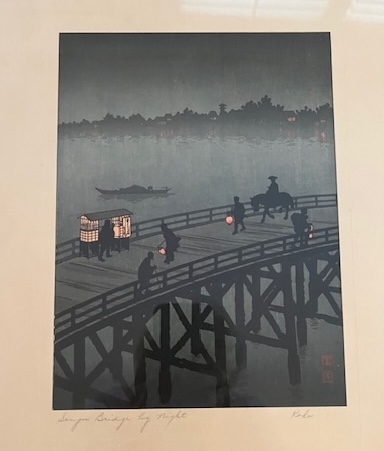

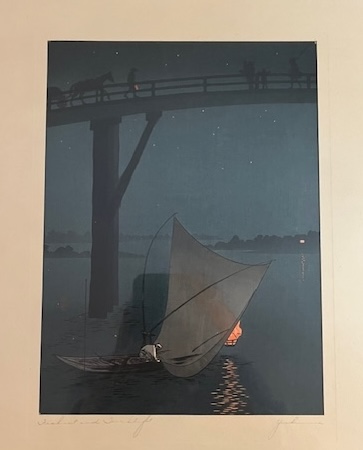

RF’s two woodcuts are nocturns, and both have lanterns aglow as part of the narrative tale of the image. The first is a fishing skiff under a high bridge with the water illuminated by an orange lantern behind the sail as the fisherman gazes. The other shows foot and horse traffic on the high bridge at night, the pedestrians carrying lanterns. There’s a technical reason that these woodblocks glow: Hiroshi “struck” each paper print between 30 and 100 times with the same woodblock but using different colors with each “strike.” The layering of colors meant that the same image created by the same block could print out in different color combinations. The most advanced technique of this color layering – called betsuzuri – was used to portray different times of day or different seasons of the SAME image. For example, in the series Seto Inland Sea, Hiroshi portrayed two sailing ships at dawn, morning, midday, afternoon, evening, at night, and in mist. The scene is of the same boats, portrayed over time.

The woodblocks were carved by Hiroshi’s staff of traditional carvers, based on Hiroshi’s sketches and supervised throughout the carving and printing process by Hiroshi himself. RF’s images contain Japanese calligraphy, which is the juzuri stamp – signifying “I the artist did this myself.”

At the age of 15 Hiroshi was “discovered” by his art teacher, a member of a multigenerational artistic family, the Yoshidas. Hiroshi was adopted into this family. His adoptive parents – the artist Kasaburo and his artist wife Rui – encouraged Hiroshi to learn from artists who painted in the Western (European) tradition. As a student, Hiroshi formed the Meiji Art Society, which merged Japanese tradition with Western traditions – combining the brushstrokes of oil painting, the color expressiveness of watercolor, and the technical woodblock traditions of Ukiyo-e.

He lived that same international style in his career, bringing his watercolor paintings to the Detroit Museum of Art in 1899, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston 1900, The Paris Exposition in 1900, and the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. He struck his first woodblock print in 1920 and established a studio in Boston in 1923 where he exhibited and sold. Soon his woodblocks were exhibited nationally in the U.S. and Europe. 1926 was his most prolific year (41 woodblock creations were made). With his artist son Toshi, he travelled to India and Southeast Asia to sketch in 1930-31; a notable image was created of the Taj Mahal in the daylight – and in the moonlight.

The Yoshida family, over four generations, and continuing to this day, spawned four male and four female notable artists, all with the name of Yoshida. This lineal progression is a tradition in Japanese woodcut art, and thus makes it difficult to date a work of art.

Speaking of Hiroshi’s son, Toshi (an artist who was born in 1911), he and his brother Hadaka, also an artist, capitalized on the previously printed woodblocks their father passed to them in 1950, and reprinted posthumously. These were not printed for the early 20th century Japanese market, and the titles are written in pencil in English, and the signature is also Western style. This is the era of woodblock prints by Yoshida owned by RF. The size is the same as the original vintage print, I’ll wager – the Oban Tate-e (a term denoting the most prevalent print format for Japanese woodblock prints) of 10 x 15” image size. Comparable sales of such images sold at auction at $900- $1,150 each.

You must be logged in to post a comment.