Bob Easton: Montecito’s Whole Earth Architect

Over the decades since he became a highly successful architect, Robert Easton has constructed custom design homes for a litany of celebrities – everyone from Barbara Streisand, Jane Fonda, Michael Douglas and Michael J. Fox to Joe Cocker, Barry Manilow, Mike Love and Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys – even Charo of “Cuchi-Cuchi” and Fantasy Island fame.

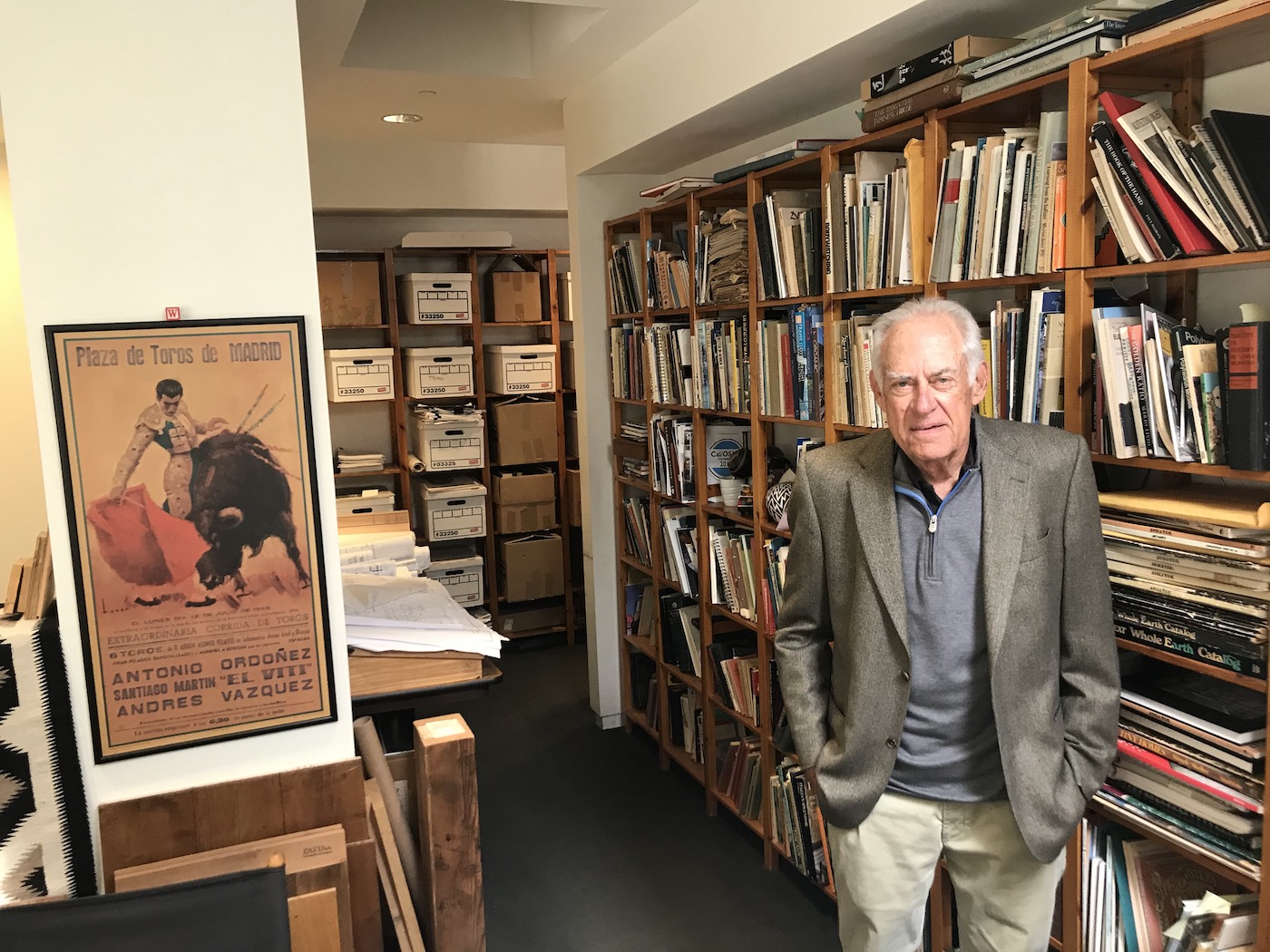

But Easton, 80, whose office is located in Montecito’s Upper Village, is also known for his high visibility historical preservation projects, including the Montecito Country Club, which he completed in 2000, and the 120-year-old Craftsman-style All Saints-by-the-Sea Episcopalian Church. In 2018,after a contractor discovered that the church lacked any substantial bracing or even a foundation below the façade, Easton won a contract to restore the church.

It was a good thing that the contractor peeked underneath the building, Easton says. “We got ahold of the original drawings and it didn’t tell us there was much bracing that was done,” he explains, meaning the building was vulnerable to a collapse in the event of a strong earthquake. “The whole front of the church facing the street was not on any foundation, just piled on stones,” he continues. “If there had been a big quake while people were sitting in a service, there would have been some real trouble.”

Work commenced on February 1 of last year. Easton’s first move: restore the church’s bell tower. The more difficult work involved rebuilding the church’s wooden framing. “The precious part of the building is the roof and the framing of the roof structure inside, which was in terrible shape,” Easton says, estimating that construction might be completed by this July. “Keep your fingers crossed,” he added by way of caveat. “There is a very busy construction industry right now, so the scheduling is tough.”

Archery and Architecture

The fact that Easton became an architect to the stars and a prominent historical renovator comes as little surprise the more one knows about his family roots. Easton’s great-grandfather was a cabinet maker and undertaker from Edinburgh Scotland who emigrated to San Francisco with his brother in the 1830s. The family’s dual profession was no coincidence, Easton says. “Undertakers were also the cabinet makers back in those days because they made the coffins.”

In San Francisco, the Easton brothers became very successful in designing and selling roll-top desks, so much so that they were ultimately able to purchase the entire city block where their factory was located downtown, between Third and Fourth Avenues and Mission and Market Streets. “They sold it three years before the [1906] earthquake and fire,” Bob Easton says, smiling. “Otherwise I probably wouldn’t be sitting here now.”

Easton’s father, James D. Easton, brought the family’s fortune to new heights, but it all started with a teenage hunting accident that nearly ended his life. While hunting on the family’s ranch in Northern California, James accidentally dropped his rifle, which discharged, wounding him in both legs. He spent nine months recovering in the hospital, during which time he read, courtesy of his father, a copy of a recently published how-to guide for hunting, Native American-style.

Hunting with the Bow and Arrow‘s author was Dr. Saxton Temple Pope, the doctor assigned to monitor the health of Ishi, the last surviving chief of the Northern Californian Yahi tribe. Before he perished from tuberculosis, Ishi taught Pope everything he knew about bow and arrow hunting, which led Pope to popularize archery as a competitive sport.

“My father was living down near Santa Cruz,” says Easton. “When he got out of the hospital he went up to San Francisco and studied with Dr. Pope.” James competed in the fledgling National Archery Association. Meanwhile, he designed the ultimate performance arrow that would come to dominate the sport. “My father was a real artist,” argues Easton. “He developed the idea of a very high precision aluminum tubing for arrows which is still used today.”

After World War Two, when the U.S. government ended its monopoly on aluminum, James Easting branched out from aluminum arrows to ski poles and other sporting devices. In the 1960s, his son, Robert’s older brother James L. Easting, expanded the family business into baseball bats and hockey sticks; both products have long been household names and remain in mass production today.

Growing up in the racially diverse Arlington Heights neighborhood of post-war central Los Angeles, Easton became fascinated with both architecture and other cultures. After completing a few drafting classes in high school, Easton designed his first building for an architect at age 16. “Then I partied for a couple of years at USC and had some fun,” Easton recalls, laughing.

Without bothering to graduate, Easton flew to Honolulu to work for a designer-builder of custom houses. After a few years, he returned to California. His studies at UC Berkeley ended with the 1965 Free Speech Movement. “It was nuts,” Easton recalls. “Nobody was paying attention to anything in school.”

Heading south in search of work, Easton built a house for a psychiatrist in Big Sur who had the untimely misfortune of driving off a cliff on Highway 1. Easton left California to attend architecture school in London.

“For a while,” he clarifies. “I never finished school. I have four years of college, but I don’t have a degree in anything. I was a smart ass.”

Dharma at Big Sur

If Big Sur is where Easton’s architecture career had seemingly stalled, it was also the location of its reincarnation. In 1967, Easton, who was living in the area, accompanied his friends Lloyd Kahn and Stewart Brand to the seaside Esalen Institute to hear a talk by the visionary architect and designer of the geodesic dome house, Buckminster Fuller. A camera crew set up their lighting equipment and recording devices before a crowd of 20 people. But two or three minutes into the talk, a passing storm took out the power. “So they took out some candles and he turned into a very grandfatherly, charming person from this technology nut which we all thought he was,” Easton recalls. “He turned into a human being. That meeting was really the genesis for the Whole Earth Catalogue.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, not Fuller, was the primary inspiration for architects of Easton’s generation. “He talked about organic architecture, how architecture should look natural and grow out of the ground,” Easton explains. “And then Bucky Fuller came along with the technological concept of the dome. I was interested in Bucky Fuller because he asked, ‘Why can’t we make the world work?’”

After following Fuller around for a while and listening to his lectures, Easton and his friends sought to implement Fuller’s ideas, each according to their abilities. “I really appreciated what Stewart Brand was doing; he was really ahead of the whole tech movement. It was fun, on the one hand, to have the skills and be trained as a classic architect, but also to be in the whole counterculture with regard to building and being part of the times.”

Easton’s friend Brand had come up with the idea for the Whole Earth Catalogue after hearing about a rumored photograph taken from outer space which for the first time in human history showed the tiny, vulnerable, blue and white home planet in its entirety. In 1968, the year after Fuller’s appearance at Esalen, Brand published his masterpiece manual – the first do-it-yourself-style guide to global citizenship ever published.

The Whole Earth Catalogue inspired an entire generation of Americans and others abroad to eschew the concept of a corporate-dominated society; it has been republished dozens of times in many languages all around the world. In 1969, along with his friend Kahn, and with help from Brand, who lent him his design facility, Easton published Domebook 1 and Domebook 2.

The two volumes documented the DIY teepee and dome-building experience, much of which was taking place off the grid or in hippie communes, featuring a wealth of black and white photography as well as lettering and logos designed by Easton. Priced at $4, Domebook 2 sold hundreds of thousands of copies. “Time magazine made a big deal out of it,” Easton recalls, “which helped us a lot.”

In 1973, Easton and Kahn published Shelter; the title a nod to the Rolling Stones song “Gimme Shelter.” This volume, translated into Spanish, French, and Japanese, has sold some 300,000 copies. “It was a combination of history and documenting the hippie building experience,” says Easton. “I designed the whole book in six months, did the logo and some of the drawings, and came up with the phrase ‘Shelter is More than a Roof Overhead.'”

While not building custom homes, Easton spent almost all of his free time between 1975 and 1990 working on Native American Architecture with his anthropologist friend Peter Nabokov, a professor at UCLA and a nephew of a Vladimir Nabokov, the famed Lolita and Pale Fire author. So far, Native American Architecture has sold 35,000 copies and it remains in print today. “It was a great experience working with Oxford Press and we won an American Institute of Architects award for the book, which I am very proud of,” says Easton. “We covered everything north of the Mexican border.”

Building and Rebuilding

Easton moved to Montecito at an inopportune time for an aspiring architect: the late 1960s. After getting a loan from his father, he purchased land in Montecito and began building a spec house with the intention of flipping the property and launching his business. But then the big storm of 1969 caused both flooding and a debris flow that wiped out the San Ysidro bridge. “It was like a mini version of the debris flow from a couple of years ago,” Easton recalls. “The flow took out houses in the Glen Oaks area. That was fifty years ago; people forget.”

For six weeks, Easton had no choice but to watch his unfinished house laying vacant up the hill until the bridge could be repaired. “As I was finishing the house and was putting it on the market, there was the oil spill, it was terrible publicity for Santa Barbara,” he says. “People quit moving to Santa Barbara. So I moved into the spec house and started designing houses and that was the takeoff for my architectural career.”

Easton’s fist remodel job: Montecito’s Old Firehouse on East Valley Road, a handsome, deteriorating structure from the 1930s that had been purchased by one of his clients. “It was a masonry building and had to be earthquaked,” he says. “We turned it into offices.” After finishing the work, Easton moved his office into the building, where he stayed for a dozen years before moving down the street to his current suite.

Because the remodel was on a high-visibility property, Easton landed his next major remodel gig: the Montecito Country Club, which had been built in 1922 but had fallen into disrepair after being sold to a Japanese firm in 1972. The club had gone through five different remodels over its history, benefiting from the work of such influential Santa Barbara architects as George Washington Smith.

But when Easton was hired to restore the building, much of its charm had faded. Among other things, the Spanish-style ornamental porticos framing the four windows on the building’s tower had been removed, either to make the building seem more modern, or because the heavy concrete materials posed a safety problem.

“So they made us put it back,” Easton recalls. After researching his options for recreating the club’s most visible exterior decorative feature, he found a company in Orlando, Florida that manufactured decorative pieces for Disney World and Universal City. “I resurrected the look based on the original drawings,” he continues. “They made these foam models and then glued them on the tower with resin and painted it to look like stone.”

Renovating the Montecito Country Club took five years and aside from a couple of pricey but necessary extras, came in on budget at $5.5 million. According to Easton, the structural condition of the club was in surprisingly good shape. Although the initial plan was for it to be constructed in the masonry style of the time, the builder refused, arranging instead for the purchase of a trainload of Douglas Fir and Redwood lumber from Northern California.

Because both woods are almost impervious to termites, and thanks to Santa Barbara’s mild climate, almost all the wood was still structurally sound. Just about everything else, though, was in dire need of help.

“A lot of it was just in disgusting shape,” Easton, himself a club member, says, laughing. “When we renovated the kitchen, I couldn’t imagine how they’d escaped the health department, but it was in desperate shape.”

In 2004, billionaire Ty Warner, creator of the Beanie Baby, purchased the club, and has since remodeled the interior with a mostly Moroccan theme; he also added a home theater, relocated and expanded the gym, put in a new pro shop and ocean-view bar, along with new men’s and ladies’ locker rooms.

Easton is grateful that Warner mostly left the club’s exterior alone. “All my changes to the building were on the exterior,” Easton says. “The new entrance, the south side, the pool house, the tennis house, the pergola – that’s all intact.”

On the Art of Drawing a Straight Line

Despite being well past retirement age, Easton still works full-time as a custom homebuilder and – with the aforementioned All Saints-by-the-Sea project the most recent example – a successful historic renovator.

“I have to say it is very rewarding and interesting to work in renovation because you are dealing with history and a lot of people’s feelings and attachment to certain buildings and spaces, he says. “You are dealing with a different set of parameters than when you design a new building.”

During a recent visit to his office, Easton took a break from examining the floor plans and elevations sketched out in the house plans that were rolled out on his desk. The plans pertained to his current homebuilding project: rebuilding a house in Calabasas that burned down in the Woolsey Fire.

“Typically how I work on these projects, no matter how complex they are, is I’ll develop the floor plan, the elevations, the structure, and weave that in with the electrical, the mechanical, and the plumbing – all the systems that are involved,” Easton tells me. “It’s like a complex chess game. When you do the structure, you’ve got to anticipate the lighting, where the heating goes, so it is intellectually stimulating and challenging. It’s fun to do.”

Although he is an accomplished draftsman who uses all the hard-edged tools of the trade and is well-versed in the complex mathematical principles of design and construction, Easton keeps an open mind for process. In fact, he credits a Tibetan monk for finally teaching him the correct way to draw a straight line. “To draw or paint a straight line, you always pull towards yourself, you never push way,” Easton says the monk told him.

Once in position and ready to draw, an artist must envision a vertical, open-space triangle between his or her pencil point or brush trip, “from there up to the eye and then down to the heart, then back to the starting point,” he adds. “Then you do your stroke and invariably it will be a pure stroke. All of architectural drawing and sketching is really the quality of that line and the consciousness you bring to it.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.