Terrible Bore: The Hellish Adventure of the Tecolote Tunnel

This political season is sufficiently fraught that your fraidy-cat columnist is going to steer well clear of the melee and write about something we can all agree on. I’m talking of course about the inarguable virtues of Communism. Ha Ha Ha. Kidding.

As has been lightly touched upon in endless cocktail party conversations (and more explosively documented in the noir classic Chinatown – a thrillingly serpentine story of murder and malice with tap water at its core), H2O in California is precious stuff. The fact is, there are few things in this world that won’t invite avarice, graft, and generally discouraging behavior when supply and demand are at odds. As Shakespeare pointed out with his ”paragon of animals” remark, humans are indeed a noble species – but we don’t always do well when faced with these little stress tests. When there is not enough of something to go around – toilet paper in one fairly recent and glamorous example – you can put money on our Better Natures taking a

momentary hike.

Once everyone came out for the ’49 gold rush and decided to stay for the movie stars and the weather, the water situation in Alta California was just waiting to go off the rails. It seems The Golden State is about 40% desert. We boast, for example, a tourist trap called “Death Valley,” if you can imagine – a natural wonder named before marketing was a thing. It would only be a matter of time before water and its disbursement in the state would become a source

of sorrow.

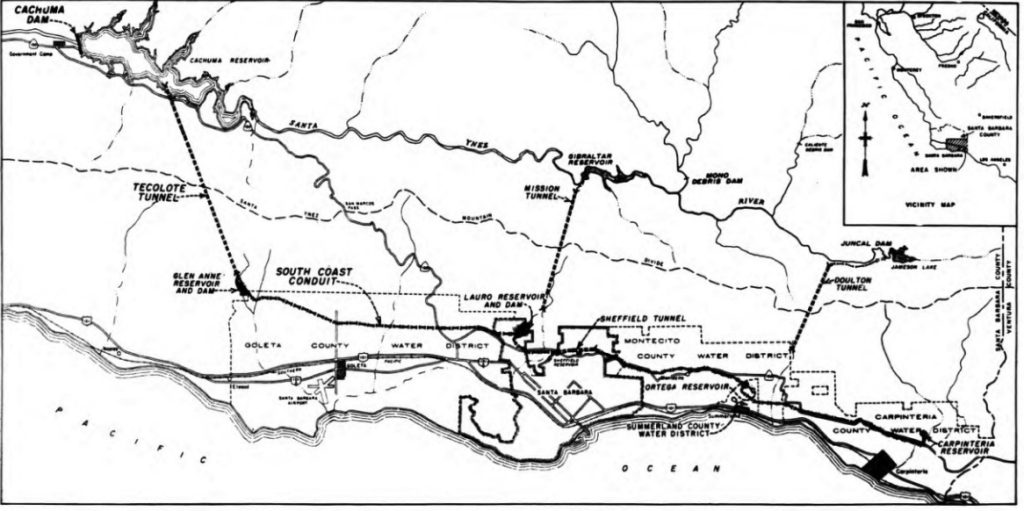

By 1937 the water sitch had deteriorated to the point that the SB County Supervisors hired an engineering firm to see what would happen if we dammed the Santa Ynez River in order to create a water catchment; what non-hydrologists call a lake. Just broaching the idea caused some heck to break loose. By the late ‘40s people on both sides of the issue were up in arms. One post-WWII worry was that a big artificial lake just sitting there in the Santa Ynez Valley would be an irresistible target for an enemy atom bomb, whose demonstrably large explosion would “wash all the people and livestock downstream into the Pacific Ocean.” This homespun concern slightly misapprehends the chief downsides of a nuclear cataclysm. Other hollered objections were that capturing and distributing the water smacked of Socialism (see ill-advised opening lines of this essay), and that Santa Barbarans would be footing a bill that would mostly benefit farmers in Goleta and Carpinteria. Following much discursive to-and-fro, the seven-year drought and severe water rationing that haunted this area in the ‘40s settled the argument. Mostly. Today when you turn on the tap in your humble abode, dwell momentarily on what it took to make wa-wa come out.

Tecolote. Not the Bookshop.

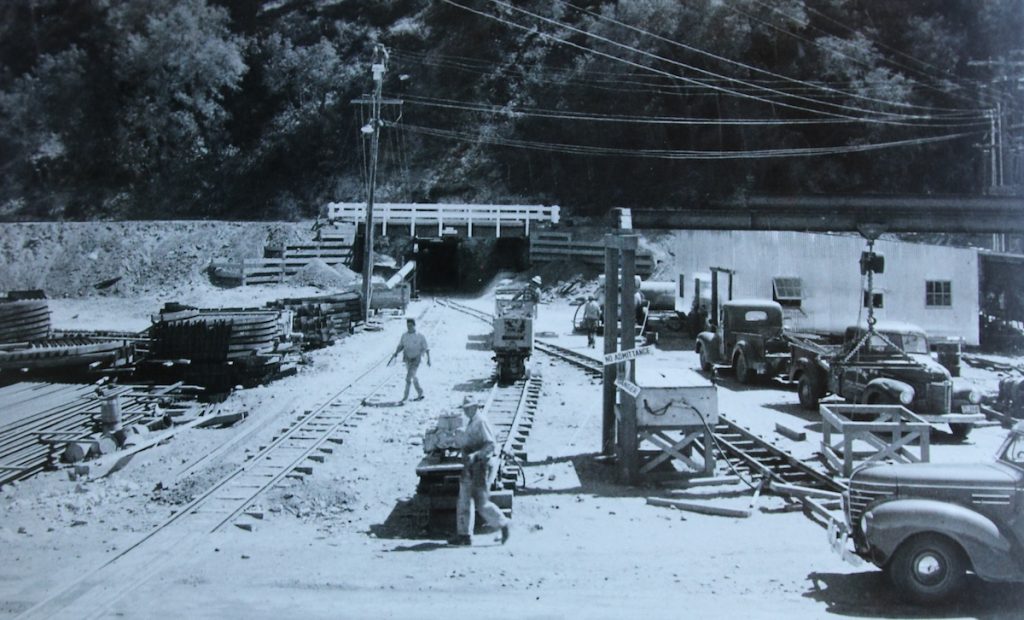

Once Cachuma Lake was created they would need to pipe that captured water down to the American Riviera, The Good Land, and surrounding parched communities with lesser Chamber of Commerce-inspired labels. To everyone’s eventual regret, this would entail boring a 6.4-mile tunnel through the Santa Ynez Mountains. Sounds fairly simple to chew through six miles of solid rock doesn’t it? Spoiler alert! On a good day it is actually very difficult to do this. The vexatious Tecolote Tunnel would become a storied pain in the derrière (to borrow from typical miner’s language), the project so fraught with miserable surprises it would make for a feature in Life magazine. Construction lasted from 1950 – 1956. A consulting engineer on the project and “one of the nation’s foremost tunnel experts” – a Pasadena-based guy named Carl Rankin – had an inkling there would be some trouble with Tecolote, having overseen several other bumpy tunnel projects. Even he was surprised by the hellish obstacles the Tecolote Tunnel presented. Budgeted at around $5M, the tunnel would ultimately cost more than $14M. It is almost as if a mountain range was not meant for boring through.

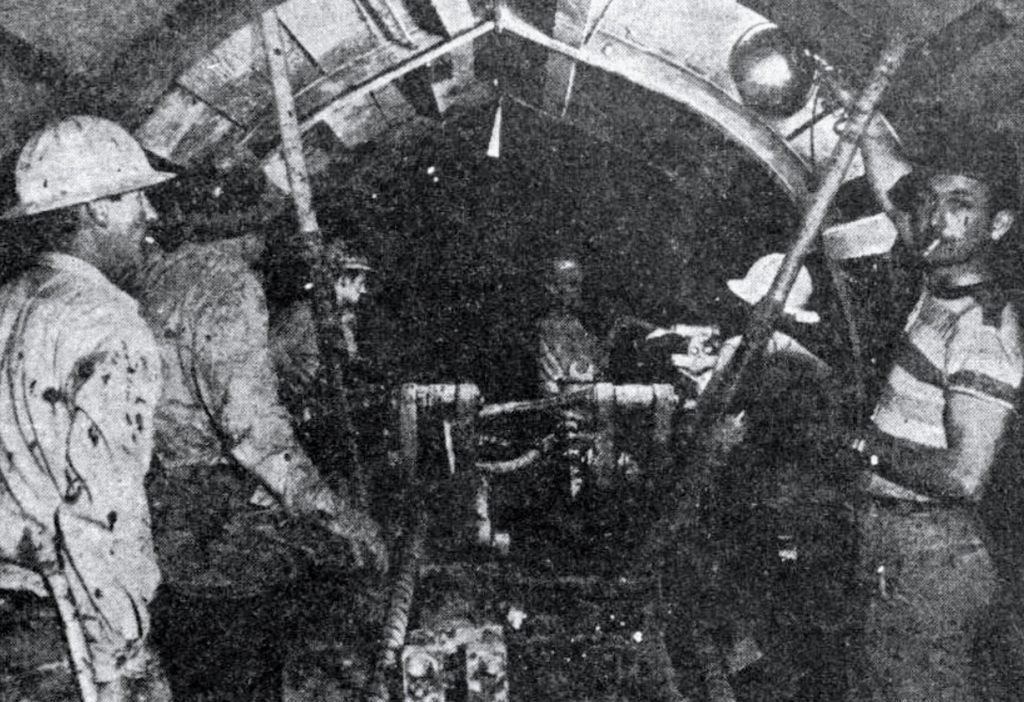

Once they got deep into the bore, the interior of the tunnel was so hot the fully clothed workers would transit in to the daily gig via narrow gauge mining cart filled to the brim with cool water; you know, like a bathtub? Surprisingly, there was No Mr. Bubble or wood-handled back brushes to make these tubs more inviting as they plunged their dungaree’d occupants into heat and darkness. What is described in accounts as a “rusty 12-inch sheet iron pipe” carried 3,000 cubic feet of air per minute into the tunnel, not that it seemed to help. Taking in a heaping lungful of wet, hot oxygen is no picnic. A commonly reported sense of mild suffocation made a shift in Tecolote a pure delight.

Explosometer

Work on the tunnel would be periodically stopped by ongoing, almost supernaturally awful eruptions of geologic bad luck. Superheated water would gush out of the solid rock at a pressure of 9,400 gallons a minute, ambient air temp for the workers averaged 107 degrees and 100% humidity, and clouds of toxic gas would fill the confined space. The air stank of sulfur. It was the sort of work environment attractive to folk who carry pitchforks and sport barbed tails.

Every so often, Bureau of Reclamation Chief Tunnel Inspector Max Hedges would produce a gizmo from his overalls and check the air for explosive gases. This little device was actually called an Explosometer, a name that may or may not have inspired confidence in the beleaguered workers. Of course photos from the period show men deep in the bowels of the Santa Ynez range working with the day’s omnipresent cigarette dangling from lips slack with misery. Explosive gas my… eye!

As for the mechanics of boring through a mountain range, the Tecolote project was begun hot on the heels of the first modern TBM (Tunnel Boring Machine), and was not able to avail itself of that helpful technology. Today these enormous and terrifying drill bits can gnaw through rock solid what-have-you at a rate of about a ½ mile a week. Tecolote’s old school method of pushing through 6 miles of mountain could, by contrast, reasonably be called a Cal/OSHA safety inspector’s pornography. The guys would drill 28 holes into the tunnel head, stick the explosives in and get out of the way – as best they could in a room two miles long and a scant 7 feet wide. How this actually worked in practice I have no idea, which is why I’m a typist.

St. Kapow

The tunnel was completed in 1956, probably to a chorus of exhausted cheers, the men’s mirthless lips pinched around filterless Marlboros. This is what it took to get water to the central coast from the SYV. It is worth noting here that Santa Barbara is named after the patron saint of Munitions – a patronage based on the explosive death by lightning of her wildly abusive father. It is unknown how many times St. Barbara was desperately invoked in the course of blasting through the Santa Ynez range, but this is just the sort of factoid a fatuously self-pleased columnist is obliged to include. You understand.

You must be logged in to post a comment.