It Had to Happen (Or Did It?)

One of my favorite poems is by a woman named Susan Marr Spalding. It’s called “Fate,” and is in two parts, each of nine lines. It contrasts the different ways life could have turned out for two presumably imaginary couples.

In the first part, the man and woman lead lives which make it extremely unlikely that they would ever meet – and yet, somehow they do meet,

“And read life’s meaning in each other’s eyes.”

In the second part, the situation is just the opposite. Although these two people, who seem to us to be made for each other, live so close together in so many ways, each somehow never actually becomes aware of the other’s existence. And so they both die unfulfilled.

The poem’s last words are: “And this is Fate!”

Of course, there are whole religions and philosophies based on either accepting or rejecting this idea, in its extreme forms. If you accept it, you are a fatalist, and have no ultimate power to determine your destiny. Followers of Allah call it “Kismet.” If you don’t go along with this line of reasoning, then, at least to some extent, you believe in “Free Will.” Unfortunately, there seems to be no scientific method of determining the truth about all this by experiment.

Free Will, I suppose, is more popular among people who are generally attracted by the idea of Freedom. That would include the U.S.A. and its citizens, many of whom will tell you that the best thing about this country is that people are more free here than in other parts of the world. Our national anthem, which was written more than 200 years ago, calls this “the land of the free.” That tends to get more favorable publicity than our other musical designation as “the home of the brave.” You can be free without anyone, or anything, else being involved. But to demonstrate bravery, you need some danger to face fearlessly, or at least without showing fear.

Traditionally, people have come to this country because, in their place of origin, their freedom was limited in various ways – sometimes, as in the pogroms of Czarist Russia, their very lives endangered. This idea is even inscribed on the huge welcoming statue which itself is called “Liberty”: “Give me … your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Ironically, the writer of those lines, Emma Lazarus, a Jewish woman from New York who died while still in her thirties, did not live to see that statue erected, let alone to know that her words would be officially associated with it.

But even the children born here are educated to believe in freedom. One collection of poems for children that I was given when I was seven years old contains Henry van Dyke’s “America for Me.” Looking westward from Europe, he described this as:

“The land of youth and freedom, beyond the ocean bars,

Where the air is full of sunlight and the flag is full of stars.”

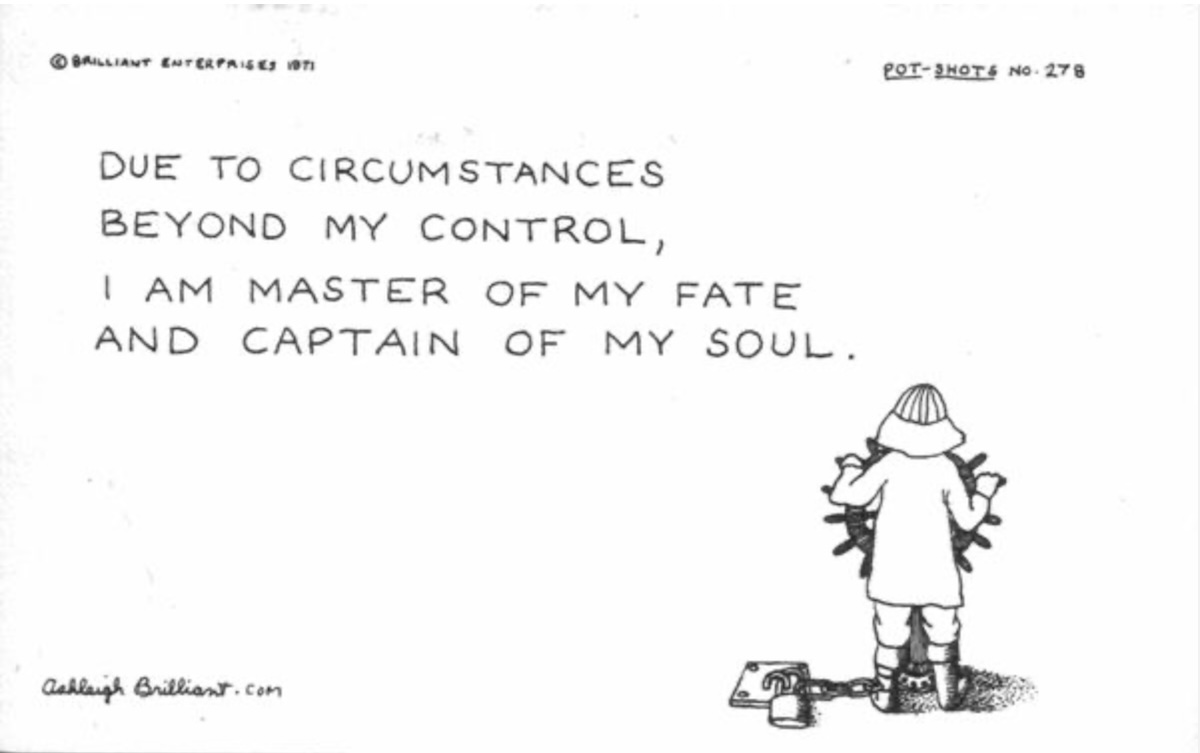

I myself, as a writer of epigrams, have inevitably touched on this subject. But my favorite position has generally been sitting on the fence – as in this profundity:

In all likelihood,

Whatever will be will be.

But it seems significant that another of my writings on this same subject, had a distinction which may surprise you. It’s the one that says,

One possible reason why I don’t believe in Fate

Is that I wasn’t fated to.

When a careful survey was made of the relative popularity of my first 1,000 epigrams, that particular one (#693) came out at the very bottom of the list. Yes, it was the least popular of all.

For that reason, I suppose, it has always had a very special place in my heart.

After all, having no children of my own, the nearest I can come to a sense of paternity is the feeling I have, as a writer, towards my own creations. Of course, I realize that they can’t all find equal favor with the Public. But to be at the absolute bottom is sort of heartbreaking to its creator – and I have to ask Why? My theory would be that in our culture, Fate is a foreign concept. You don’t find football coaches telling their team that Somebody Up There has already decided the outcome of the game. Any vocal believer in Kismet would probably be kicked off the team. So, once again, I can only take a non-committal position:

I could try resigning myself to fate – but what if fate refuses to accept my resignation?