Carnegie Slept Here

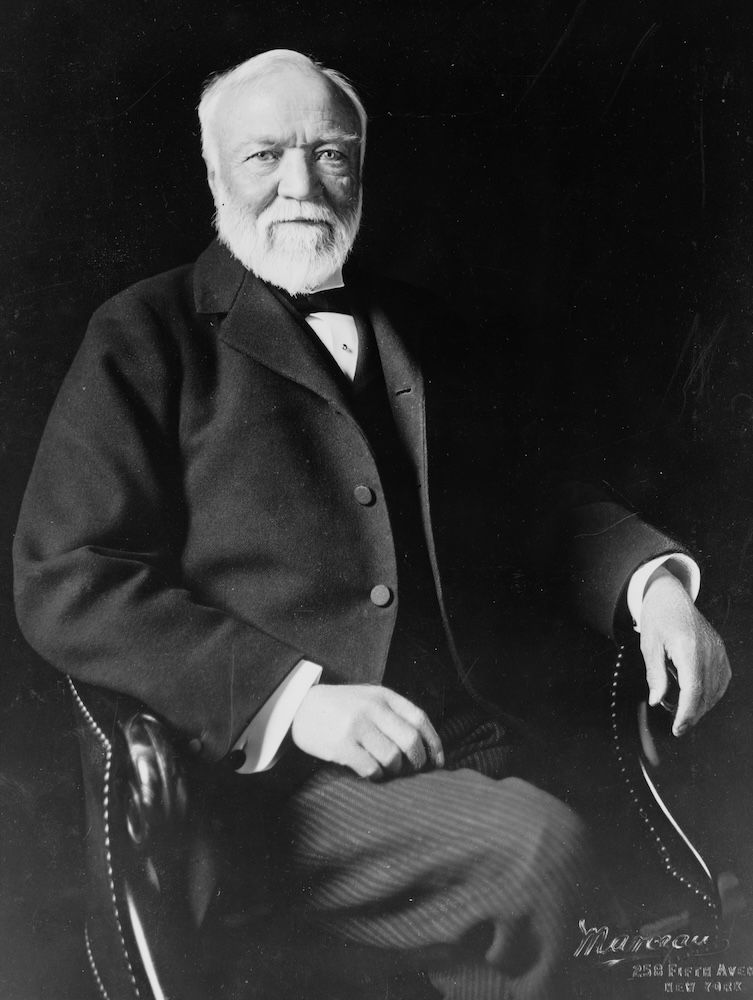

In early 1910, the local newspapers were abuzz and the paparazzi were sharpening their pencils in anticipation of the arrival of the great philanthropist and Steel King, Andrew Carnegie, in Santa Barbara. Carnegie had left Pittsburgh on February 15 in the company of his wife Louise, daughter Margaret, his associate Charles Lewis Taylor, and four servants. Taylor, the president of the Carnegie Hero Fund, had been wintering in Santa Barbara since 1900 and his glowing descriptions of the healthful resort town piqued Carnegie’s curiosity. He determined to visit.

Their journey did not have an auspicious beginning. While Carnegie and entourage were preparing for dinner in the private car “Olivette,” an incoming train struck the car. The passengers were thrown to the floor and several sustained painful cuts and bruises, according to a United Press report that ran nationwide. Nevertheless, the train was able to depart for Chicago where the “Olivette” was transferred to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe line.

As the locomotive sped west over the next few days, journalists were disappointed that Carnegie did not make any appearances at train stops. Rather, he remained aboard the “Olivette” with the shades drawn. Most towns didn’t know they’d been “visited” by the great man until the station masters reported the train’s passing. The people of Henrietta, Missouri, were especially excited that he had streaked by.

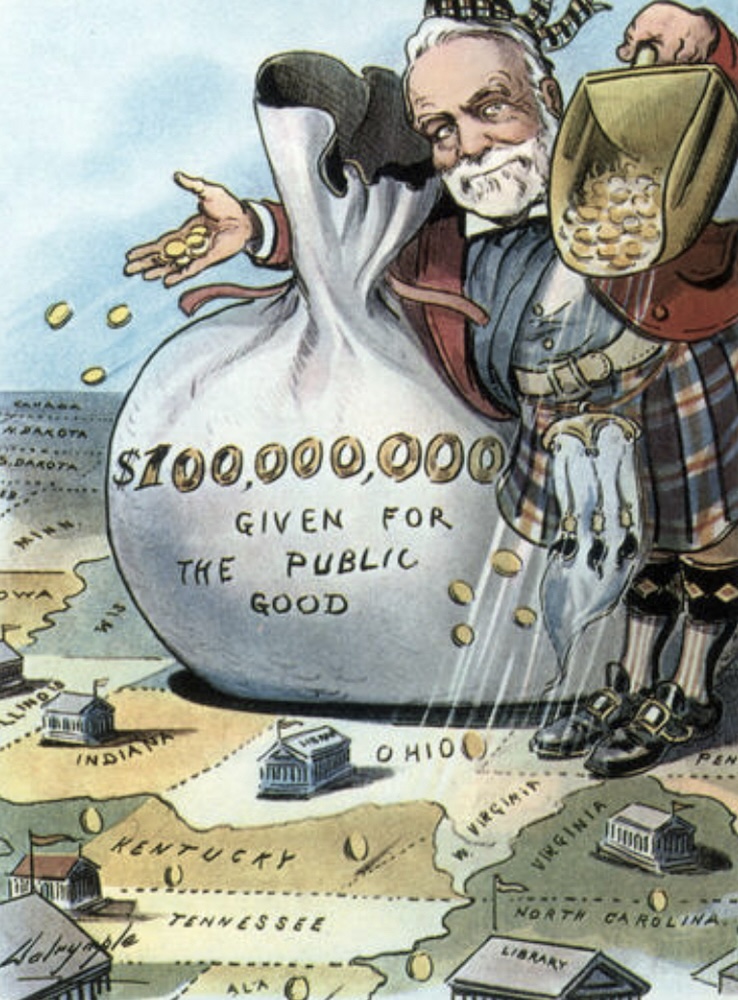

With nothing immediate to report on the four days it took the Carnegie party to travel to Santa Barbara, national journalists resorted to background stories about the rise of Carnegie’s steel empire, his political views, and the beneficence of his philanthropy, especially the community libraries.

In Santa Barbara

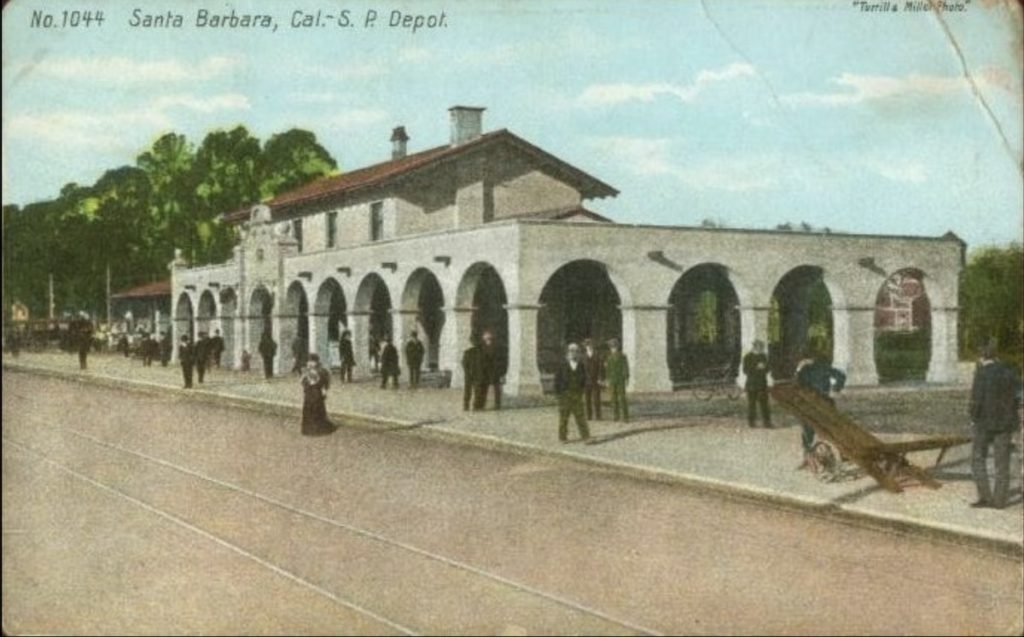

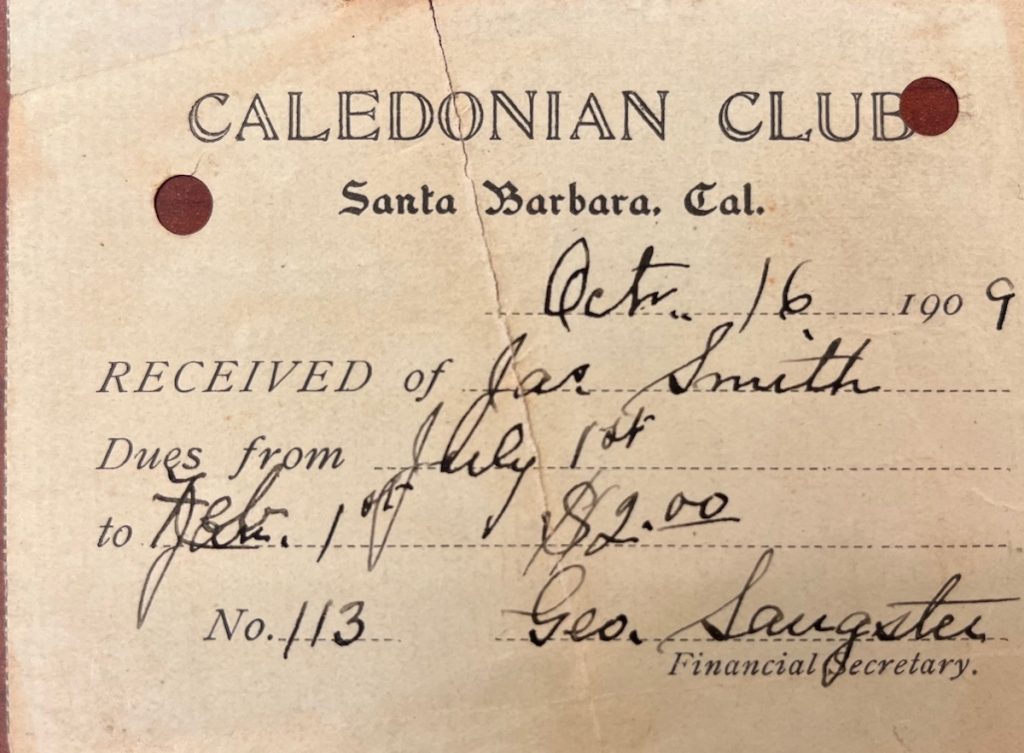

When the Southern Pacific train from Los Angeles pulled into Santa Barbara station on February 18, the kilted members of the year-old Caledonian Club greeted Carnegie with bagpipes and roses. The excited crowd of several hundred pressed close to the debarking party, but Piper Robert Calder cleared a path for the Carnegies and swept the crowd aside while playing “The Campbells Are Coming.” Carnegie accepted roses from a wee lass and expressed his thanks to the Caledonians before departing in a waiting carriage as Cesar La Monaca’s band played “The Blue Bells of Scotland.”

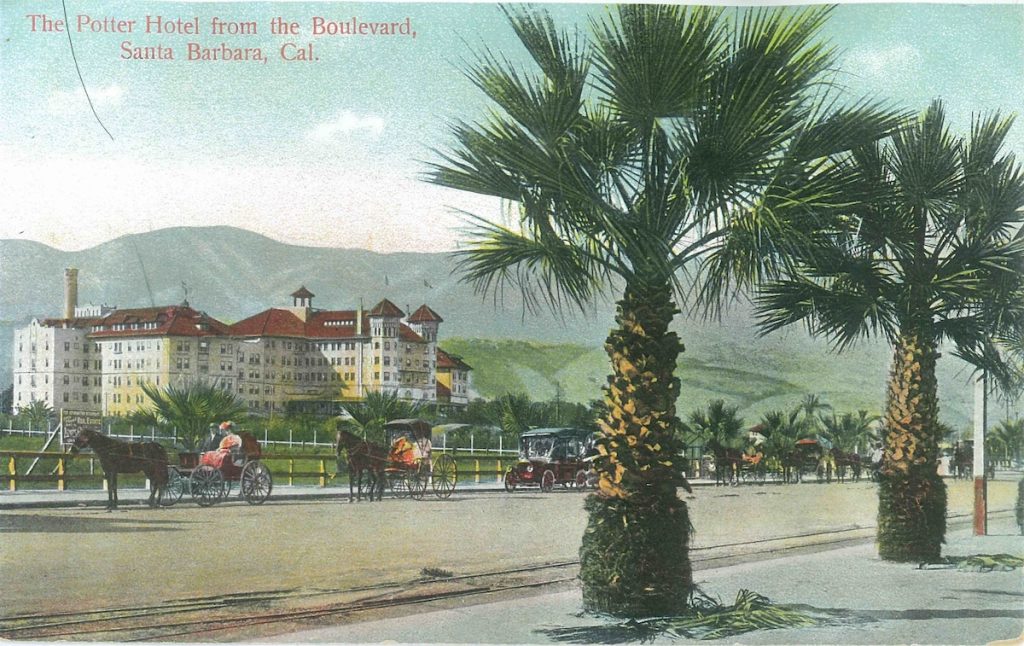

At the Potter Hotel, the Carnegie party went straight to their suite of rooms on the fourth floor and were served dinner in the sitting room of the tower. Carnegie made it known that he was to be left strictly alone. He quickly settled into a routine of a morning stroll around the Potter grounds and along the beach. Afternoons were reserved for excursions in a Pierce Arrow, which had been reserved for him, or just relaxing at the hotel. Evenings were spent in the lobby or smaller rooms off the hall where he chatted with friends or enjoyed a quiet game of cards. One evening, however, he came down to the lobby to listen to La Monaca’s band, which again played “Blue Bells of Scotland” in his honor. Eventually small entertainments were added to the pattern of his days.

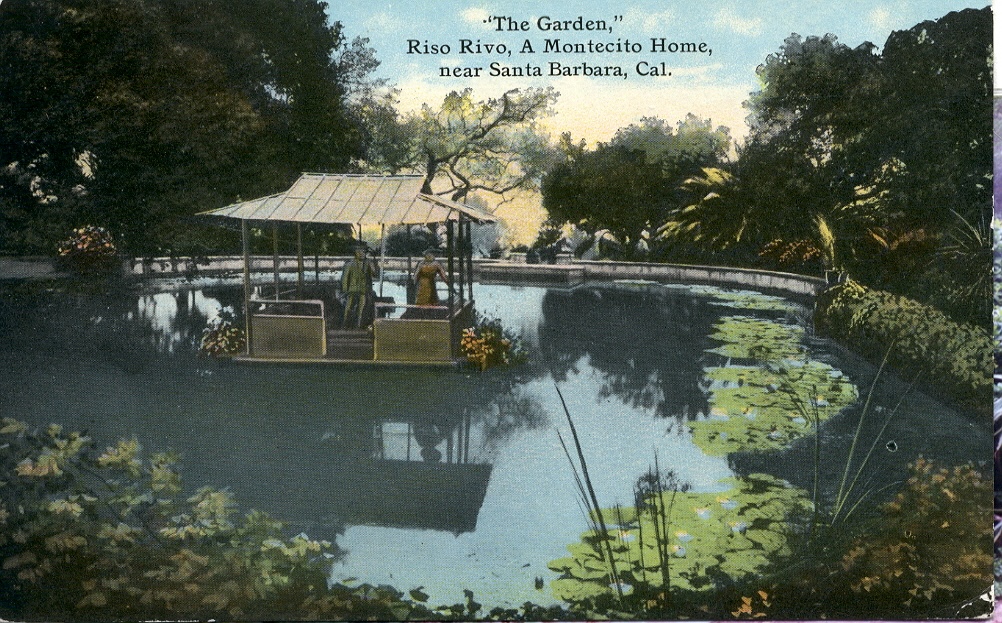

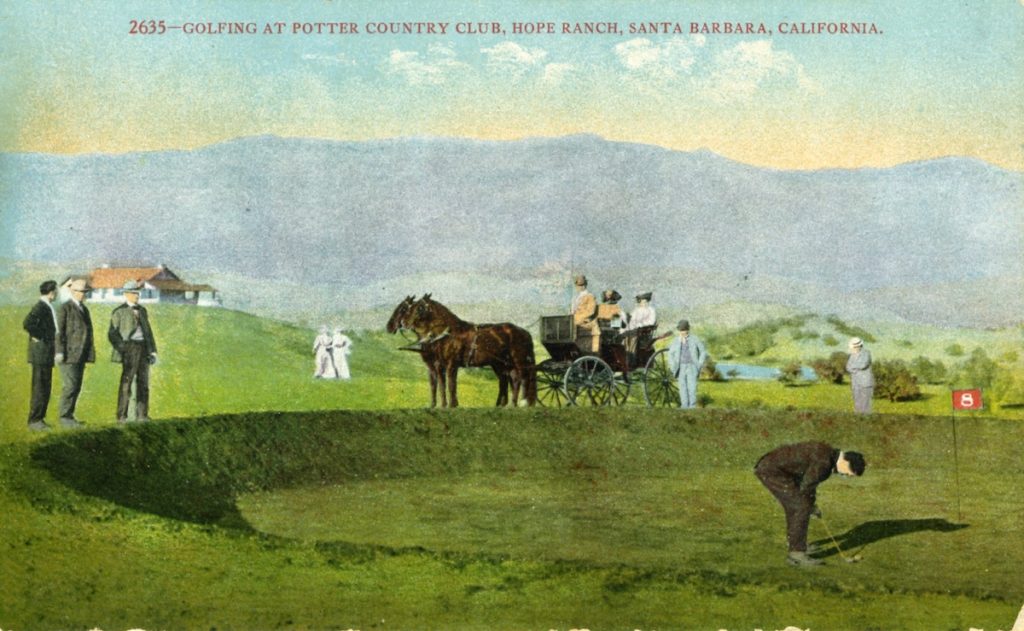

Automobile excursions through Montecito found him especially impressed with Charles Frederick Eaton’s estate, Riso Rivo. Other excursions and activities included a motor trip to Casitas Pass, lunch at the Potter Country Club (today’s La Cumbre Country Club), and a party at the Vegamar estate (today’s zoo) owned by Lillian Beal (later Child). At a Santa Barbara Country Club luncheon given by Charles Taylor, Carnegie, whose stay was nearing its end, was fêted with several speeches including one by Edward Payson Ripley, president of the Santa Fe Railroad who had arranged for the private car “Olivette.”

On the evening of his departure, Carnegie expressed his surprise and pleasure with Santa Barbara. “If they try to make heaven much better than this, they’re likely to make a mistake,” he said. He also expressed his delight with friends “whose thoughts were of his wishes and comfort, who protected him from the cares of business which he came to escape, from the appeals of charitable institutions and mercenary or mendicant individuals, and from the approach of insistent journalists.”

Uncle Charley

Philadelphia-born Charles Lewis Taylor had a longstanding connection to Santa Barbara. His brother Levi had come to California in 1873 to engage in the sheep business near Ventura. He married Maria De la Guerra, a granddaughter of pioneer Capitan José De la Guerra, at the De la Guerra casa in 1881. They lived on the Simi Ranch and in the town of Ventura. Levi died in 1894, and Maria eventually returned with their daughter Sally to live with her family in Casa de la Guerra.

Charles Taylor, whose father had been the treasurer of the Pennsylvania Central Railroad, graduated from Lehigh University as a mining engineer. He worked at various iron and steel companies, eventually becoming superintendent of several. In 1893 he became assistant to the president of Carnegie Steel Company. In 1900, he made his first visit to his sister-in-law in Santa Barbara. From that point on, he began to spend many winters in Santa Barbara, and Sally visited him and her cousin Lillian in Pittsburgh.

At some point, Uncle Charley purchased a two-story Queen Anne home for Maria and Sally at 1528 Chapala Street. By 1907, he was chairman of the Carnegie Relief Fund and president of the Carnegie Hero Fund. He had also built a bungalow designed by local architect Francis Wilson on the lot next door to Maria’s home. His yearly visits continued, and he often brought his wife and daughter to Santa Barbara.

The Hero Fund was set up to reward deeds of heroism. Those rewards were more complicated than just cash prizes, and they truly expressed Carnegie’s vision of giving. The awards were intended to relieve distress caused by those heroic acts, to reimburse losses met through injury and to provide pensions for the dependents of those who lost their lives seeking to save others. In one case a captain – who had rescued passengers and crew from another ship – was given a gold medal and $6,500; $1,500 to liquidate his mortgage and a fund of $5,000 from which he could draw to educate his son.

Taylor was an intimate of Andrew Carnegie. At the 1908 dedication ceremony for Taylor Hall at Lehigh University, Carnegie said, “[Taylor] has an opportunity afforded few men … he is one of the Carnegie veterans, and they all seem to be sons. They never have to make appointments and ask when they can see me.”

Henry Pritchett

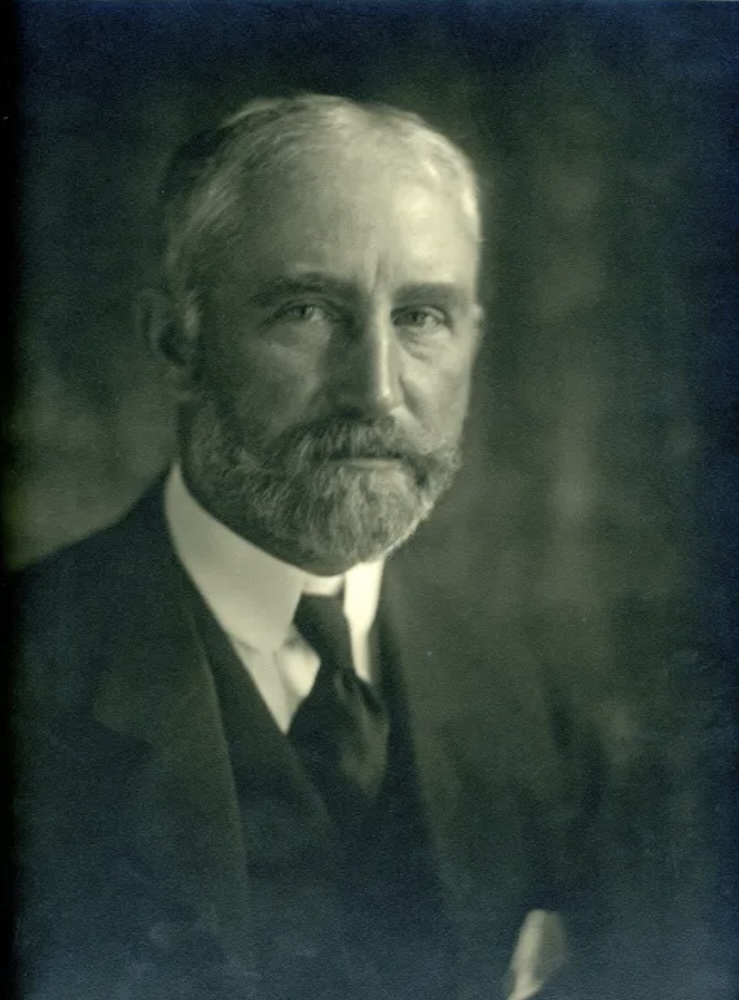

It was Taylor’s glowing descriptions of Santa Barbara that had inspired Carnegie’s visit, and it was Carnegie’s visit that inspired the visit of Henry Smith Pritchett, another Carnegie veteran and president of the Carnegie Foundation’s Education Fund. Pritchett was an American astronomer and mathematician who had become head of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey and later president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before joining the Carnegie Corporation. At the end of March 1910, he passed through Santa Barbara on his way to San Francisco and stayed at the Potter Hotel.

By 1912, the local paper asserted that Pritchett was now considered to be an official Santa Barbaran, having lived there for nearly a year and having taken an active interest in local affairs. He had suffered a physical breakdown and regained his health in the Channel City’s salubrious environment. Soon he and his wife became annual summer visitors, and after renting for several years, they built a home on at 230 Junipero Plaza which was completed in 1916.

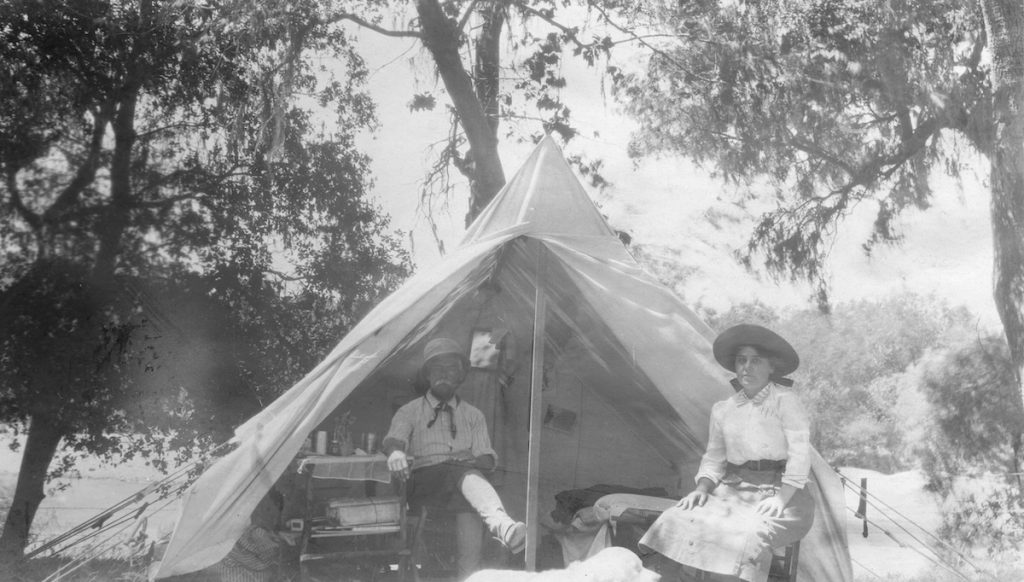

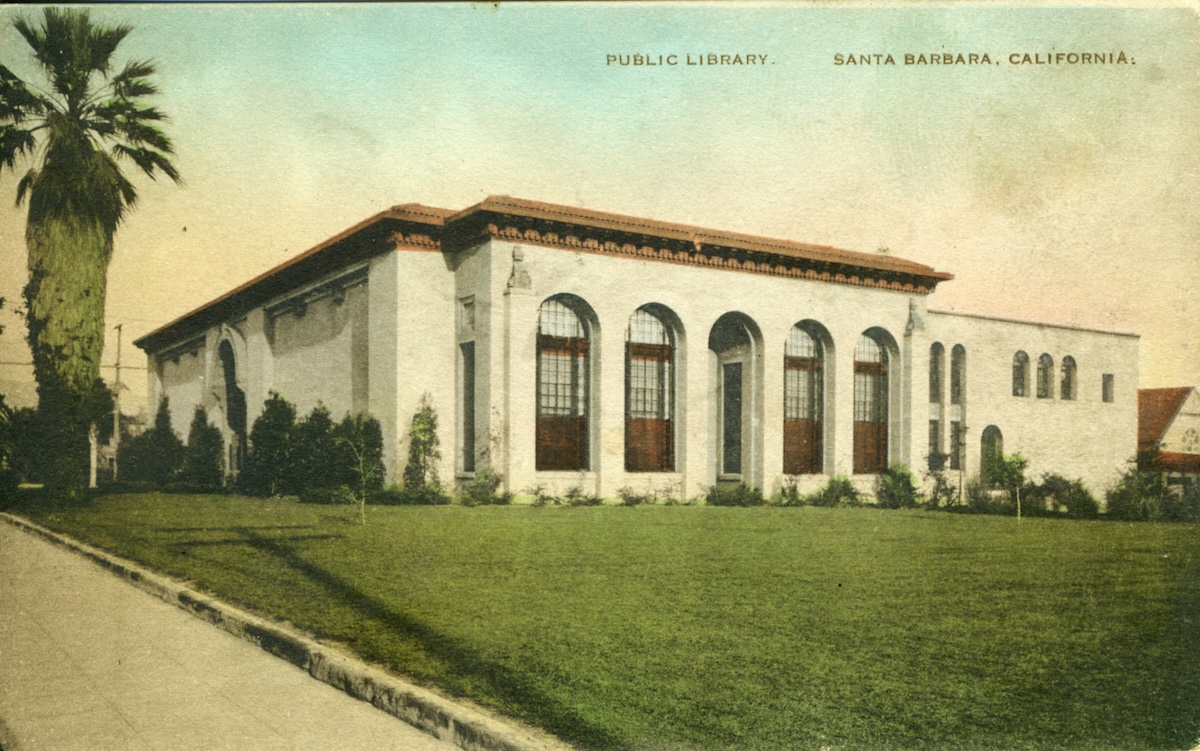

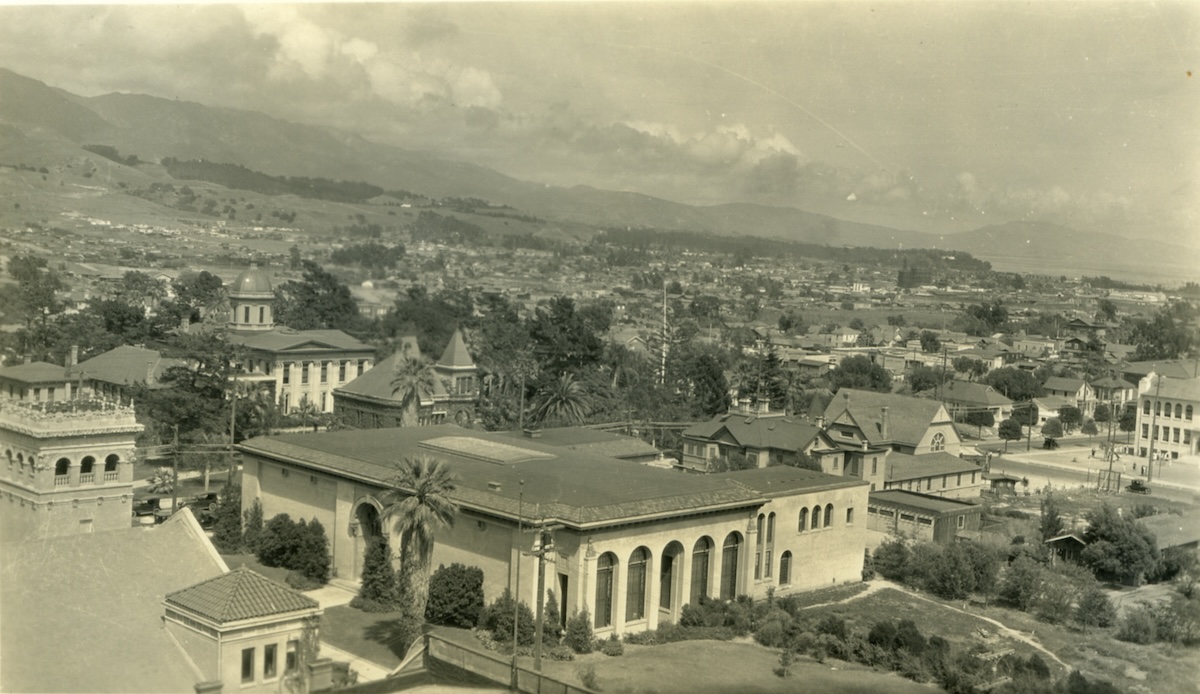

In 1914, Charles Taylor initiated requests for Carnegie funds for a new library building for Santa Barbara, and Henry Pritchett added his voice to the project. In August of that year, fifty representatives from Santa Barbara County, City, and Chamber of Commerce gathered for a moonlight picnic at the oak studded glen of C.D. Hubbard’s ranch in Carpinteria. The gathering was in honor of the news that the Carnegie Foundation was donating $50,000 toward the construction of a new library for Santa Barbara.

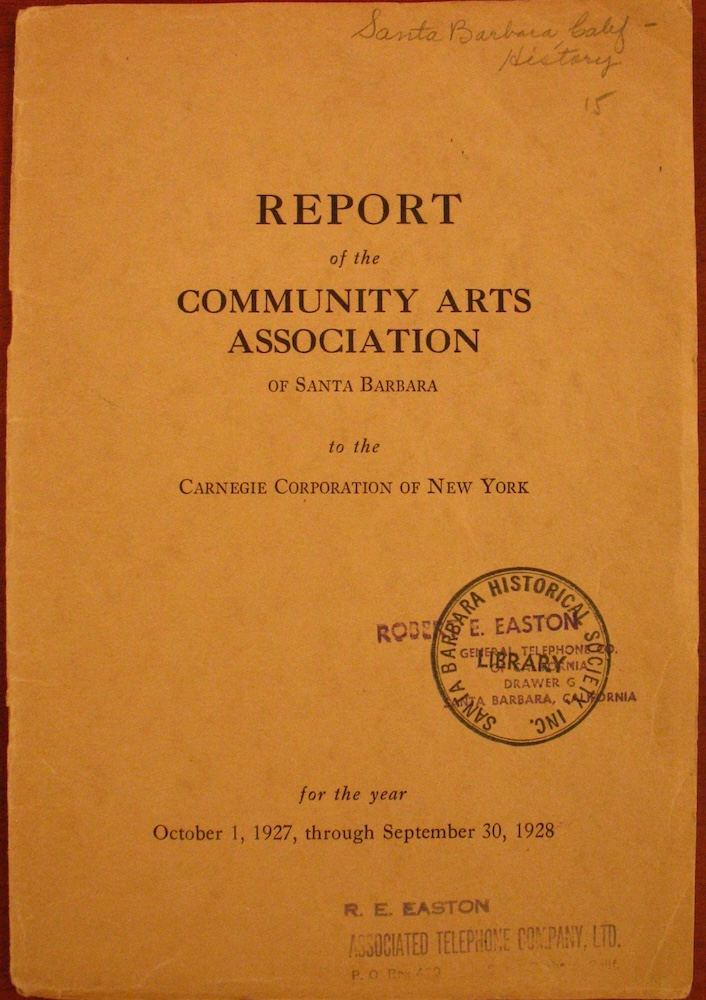

Andrew Carnegie died in 1919, but his charitable foundations lived on. In 1921, Taylor and Pritchett teamed up again, this time to ensure that the fledgling Community Arts Association would receive a five-year grant for its programs which came to include the Community Arts’ Drama, Music, and Plans and Planting branches, as well as the Santa Barbara School of the Arts. The grant came through in November 1922 and was extended for three years after the 1925 earthquake to help the programs redevelop.

Taylor died in February 1922 after suffering a stroke. His obit credited him with devoting the last 20 years of his life to the alleviation of suffering and advancement of learning and peace. His many personal contributions to Santa Barbara institutions such as Cottage Hospital were much appreciated.

Henry Pritchett continued to summer in Santa Barbara where he involved himself in all aspects of the community. He was often sought out as a speaker on various subjects, and he was a prolific writer on lofty topics. He died in 1939. Andrew Carnegie may have remained exclusive and reclusive during his one visit to Santa Barbara, but the community benefited tremendously from the two Carnegie men who adopted the Channel City as their own.

Sources: The Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie; contemporary news articles; City Directories, U.S. Censuses, Wikipedia, obits

You must be logged in to post a comment.