Montecito’s Hot Springs Canyon Revised from MJ Vol. 17 Issue 19

By 1880, Montecito’s Hot Springs were so ancient that the Morning Press felt compelled to write their history. The hot springs, the article said, had been used by the Chumash since time immemorial. After the coming of the Europeans, the springs, though belonging first to the Pueblo and then to the City of Santa Barbara, “were preserved for the use of the citizens who chose to take benefit of their healing properties, or for thrifty washerwomen.” In fact, whole families used to camp near the springs for several days while the women pounded the dirt out of that season’s laundry and laid the items over accommodating bushes to dry.

When Pvt. Walter Murray arrived in Santa Barbara as a member of Company F of the 1st New York Volunteers in April 1847, he was placed on garrison duty and had plenty of free time to explore the area. In his memoir he wrote, “One of our favorite resorts was the ‘Sulphur’ or hot springs.” After negotiating the overgrown trail, he and his companions found “three or four springs of differing temperatures and different ingredients, if one may judge by the color; one of them being a bright pinkish hue, another green, another indistinguishable from ordinary water.”

In later years, studies revealed some 20-plus springs ranging in temperature from 60 degrees to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. The medicinal properties of these springs were believed to be of great value in treating a multitude of diseases. Medical scientists of the time asserted that rheumatism, gout, Bright’s disease, liver troubles, and bladder irritation were sure to disappear with daily treatments of the spa waters. The antacid quality of the water benefited dyspepsia and conditions of the blood and urine. In addition, syphilitic and scrofulous contaminations and chronic skin diseases greatly benefited from bathing in the salubrious liquids.

Murray reported that each spring flowed into a natural basin in which he and his friends would often immerse themselves. “These springs,” he wrote, “would make the fortune of any town in the United States but here are left alone and deserted, visited alone by the native sick or the American sojourner in Santa Barbara.”

Development

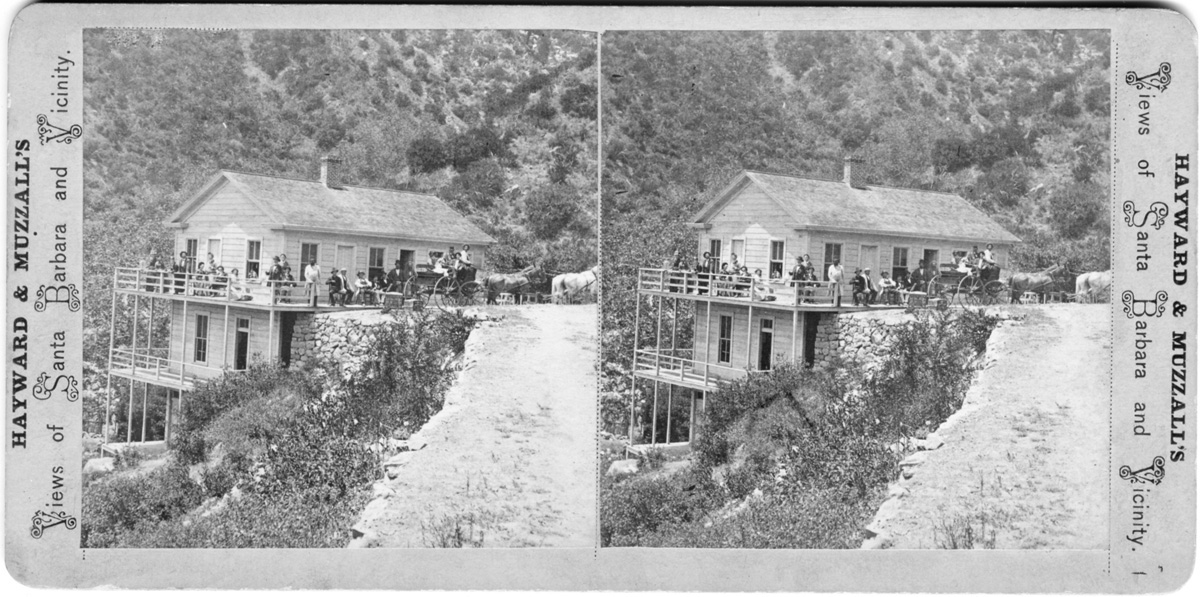

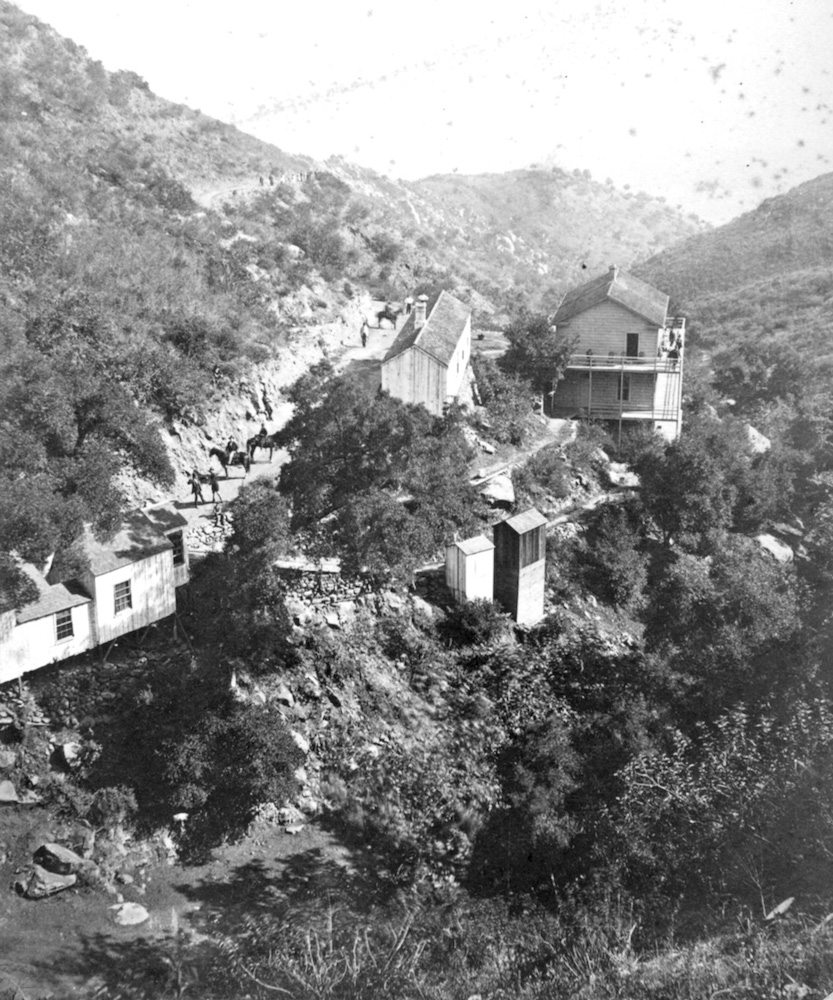

In 1855, Wilbur Curtiss, whose health was broken after years of mining, was shown the springs, which worked a miracle on his ailments. As his health improved, he envisioned a lucrative future for himself as owner and operator of a thriving health resort. Much to the dismay of the 1880s reporter, who bemoaned the loss of public ownership of the springs, Curtiss made a pre-emption claim and set about making improvements. He started with tents, then huts, then cottages and then a hotel. He also built an access road to the resort.

Curtiss’s health may have improved by his association with the springs, but his fortune certainly didn’t. The road was subject to washouts in heavy rains, and in 1861-62 one of the men living in a canvas shanty at the springs was killed by a landslide. Realizing the difficulty and perils of operating a resort in such a remote and precarious site, he decided to interest investors in the construction of a hotel at the mouth of the canyon to which he planned to pipe spring waters. His prospectus promoted a lodge with 46 bedrooms, many with private bathrooms and sitting rooms. Unfortunately, investors failed to materialize.

In 1871, wildfire destroyed all of Curtiss’s buildings in the canyon. It took years to rebuild, and he went into debt. In 1877, his property was sold in a foreclosure sale, after which a succession of owners and managers tried their hands at running the enterprise. In 1886, at the height of the California land boom, Edwin H. Sawyer bought the resort and its attendant 320 acres. When the boom went bust the following year, he tried to interest others to manage or buy the resort, but somehow the property always ended up back in his possession.

Testimonial

In 1885, Katie Payne was visiting friends in Santa Barbara who introduced her to handsome young lawyer Will Taggart (James William Taggart, one of the first justices appointed to the California Court of Appeals). Will introduced her to the Hot Springs where together with her friend Lillie Calkins, they lunched, bathed, and hiked to the popular Lookout Point. The following June, Katie suffered from headaches and, perhaps, pining for Will. Her doctor prescribed several weeks of treatments at the Sulphur Springs Resort in Montecito. After a morning sulphur bath and hike, Katie was treated to mud packs, arsenic drinks, and arsenic baths in the afternoon. In the evenings, guests gathered in the parlor where Katie joined in the entertainment by playing guitar. On the 4th of July, the guests marched to the halfway house accompanied by Katie’s patriotic tunes played on paper and comb. Later they watched the fireworks and rockets sent skyward from the city below.

During this time, Katie renewed her acquaintance with Will Taggart. The hot springs did their work; Katie’s ailments disappeared and the two married in 1887. Years later, when their daughter was ill, they obtained permission to take her to the then closed Hot Springs Resort. Taking their own supplies for the six-week stay, they found the hotel occupied by a colony of rats. Each night Victor the caretaker sat in the rafters spearing rodents, bagging 40-50 each night. At the end of their stay, however, their young daughter, who had somehow survived drinking a multitude of glasses of sulphur and arsenic water, was proclaimed well.

Canyon Dangers

Fire and rain were constant threats to the resort. In 1889, for instance, heavy rains sent a boulder tumbling that demolished three sides of a bathhouse occupied only moments before by the children of Reverend P.S. Thatcher. Mountain lions and coyotes decimated hotel livestock, and downstream riparian owners objected to people with “scrofulous complaints” bathing in their drinking water.

In 1905, Edwin Sawyer was finally relieved of his “white elephant” when a group of investors bought the property. Once again talk of a hotel at the mouth of the canyon surfaced. Once again, nothing came of it. In 1910, W.H. Bartlett and S.P. Calef bought the Hot Springs lands of now 480 acres, and in 1914 organized the Hot Springs Club, “for the enjoyment of the waters of said springs.” Initially the exclusive club was comprised of only 15 members.

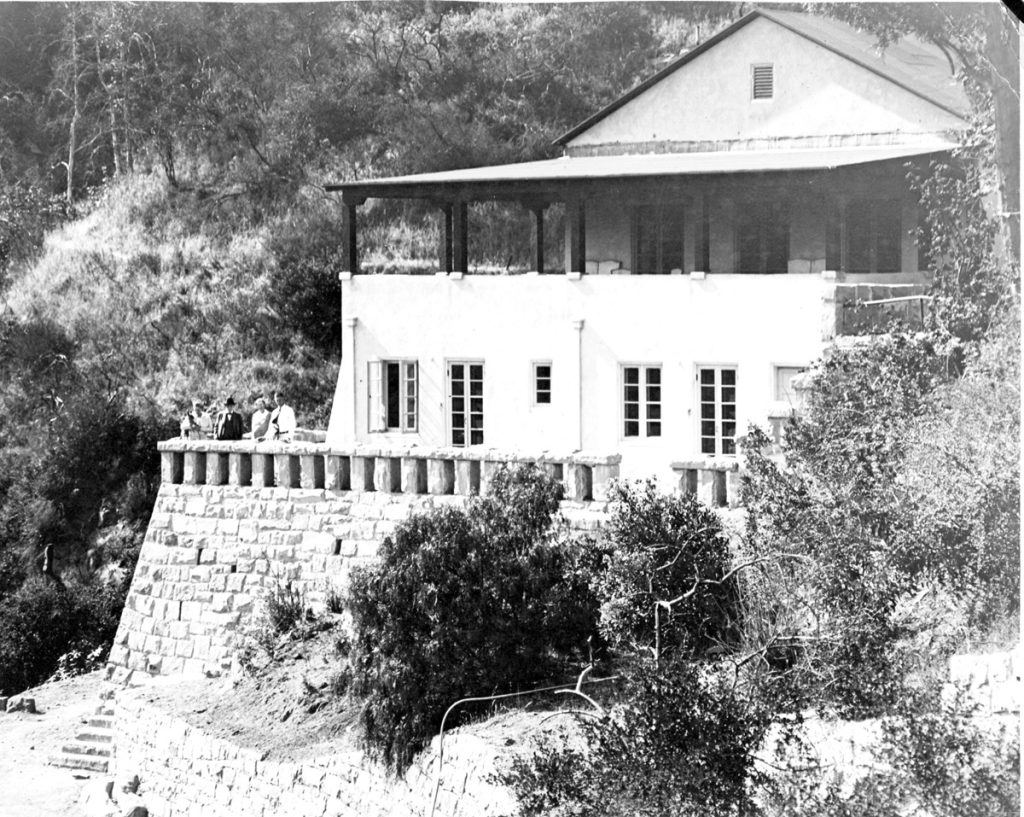

In 1921, fire destroyed the old hotel, and a new clubhouse was built on its stone foundations. Eventually falling into disuse, the property was acquired by Kenneth Hunter, Sr. between 1958 and 1962 when he completed purchasing the shares of all the Club owners. Hunter repaired the building and made improvements only to have the devastating Coyote Fire of 1964 turn his enterprise to ashes. In 1986, Hunter sold his shares of the land to McCaslin Properties who planned to develop the acreage.

Hiking the Trail

Hikers have been using the Hot Springs trail for centuries. In his memoir of 1847, Murray describes the overgrown trail that led to the enchantingly sequestered springs in the canyon. Rides to the hot springs were a favorite excursion for residents and visitors alike in the 1880s. The 1904 “Guide to Rides and Drives in Santa Barbara and Vicinity” promoted the springs and the view from Lookout Point. The Hikers, a club founded in 1913, held its inaugural outing on January 11, 1914, with a hike up Cold Spring Trail and down Hot Springs Trail. Nevertheless, despite its popularity, ever since Curtiss filed his homestead claim, hikers and bathers had been trespassing on private property.

Owners of the hotel, restaurant and spa in the 1880s had complained about picknickers who used the land and spent no money. A hundred years later, the tolerance of the property owners dried up when trespassers broke the pipelines of the Montecito Creek Water Company to fill makeshift tarp-lined spas and built campfires in the fire-prone canyon. One man went so far as to dam the creek, build a cement-and-tile spa, and hand out business cards with a toll-free number!

When the owners of the now 462-acre canyon property wanted to sell, the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County launched a successful capital campaign and purchased it in 2012. The Trust then spent another 19 months working with government agencies, utility companies, and neighboring owners before being able to transfer the deed to the U.S. Forest Service, thereby returning Montecito’s Hot Springs Trail to public ownership.

Now, twelve years later, the hot springs are in the news again as the increasing popularity of the trail and the springs has brought both locals and out-of-towners to the site. The conflicts are many and range from parking spaces to the use of the pools themselves to the fear of fire. In 1860, the population of Santa Barbara was 2,351 people. The impact on Santa Barbara trails and the hot springs was miniscule. Today, the local population of Montecito, Santa Barbara and Goleta tops 127,000. Add an out-of-town element lured by social media and advertising, the pressure on the trail and surrounding area is tremendous. There are also concerns about the status and condition of the access easement. Tempers have flared.

It would be well to remember who has the say on the use, if any, of the hot springs and the trail. As part of the Los Padres National Forest, one could assume that the governing body of what happens with the springs is the Forestry Service. As far as the rights to the water, that is a question, I believe, for the Montecito Water District, the Montecito Creek Water Company, and the Forestry Service, as well.

(Sources not mentioned in text: articles by Stella Haverland Rouse; Mineral Spring and Health Resort of California, 1892; vertical file of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum; historic maps; “The Montecito Hot Springs Experience” by Klara Spinks Fleming, Noticias, Spring 1980; News-Press 26 December 1989; Southworth’s “Santa Barbara and Montecito,” 1920; Myrick’s “Montecito and Santa Barbara”; city directories, U.S. Census, contemporary news sources.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.