Miki Dora Was Here

Troubled Surf legend Miki Dora – the Dark Prince of Malibu – remains a cipher. His lifelong desire to live in the moment has made him a mythic figure in the surf pantheon; a stature that in his lifetime royally pissed him off. Pop culture shorthand has reduced Dora to a James Dean for the surf set, the London Times once even calling him “Kerouac in board shorts.” Dora’s elaborate efforts to dodge the norms and traps he saw at every turn only magnified his reputation as a mercurial outlier, a smoldering surf pioneer of few words. All he wanted – all Miki Dora ever wanted – was to be left alone. The desperate lengths he went to in pursuit of that grail would put him into the cage he’d spent his youth fleeing.

A surf god and unwilling totem, Dora lived simply to surf. What sounds plainly childlike would occasion a lifetime of petty thievery, scamming, and double-dealings, all in the name of unfettered days and nights. His ‘70s-era disappearance would make him a globe-hopping enigma one step ahead of the law, his legend (to his own profound annoyance) only amplified once he left the surf scene. By the time the little boy lost finally came to ground, he would be a 67-year-old man falling into the arms of his father, living out his final days in Montecito.

Beach Blanket Budapest

This most American of icons, Miklos Dora III was born in Budapest in 1934. His mother, a Los Angeleno named Ramona Stancliff, had met his father in Hungary while traveling the world with her eccentric mother and sister. Miklos Sr., a Royal Calvary officer, was smitten. He and Ramona married in Hungary, but the young family moved in short order to LA, where the former cavalryman opened a restaurant called Little Hungary.

Miki was six when Ramona and Miklos Sr. split and she married charismatic legend-in-the-making Gard Chapin. Tall, blond, muscular, and angry, Chapin was a striking early longboarder whose mastery of the unwieldy 90 lb., ten-foot redwood plank made him a kingpin, and he raised Miki to similarly walk on water. Miklos Sr. had already introduced young Miki to surfing at San Onofre, and with his stepfather Gard’s guidance, Dora would become a preternatural longboard surfer. Dora’s profoundly relaxed style – walking gracefully around the longboard as it slipped down the front of the wave – would earn him a nickname; “Da Cat.”

At home, Chapin was a ruthless disciplinarian, and a sometime terror for his stepson, Miki. Neither was Chapin much liked on the beach, his surly sense of claiming or owning a wave new to the scene that often saw several pals sharing a ride into shore, laughing, and goofing. It’s been said that the indefinable Miki Dora absorbed old world gentility from his Hungarian father, and both his revulsion for norms and his angry loner persona from Chapin. In any case, Dora’s two fathers effectively informed the surfer’s fractured personality throughout this life.

Curtain Fall and Dora’s Escape

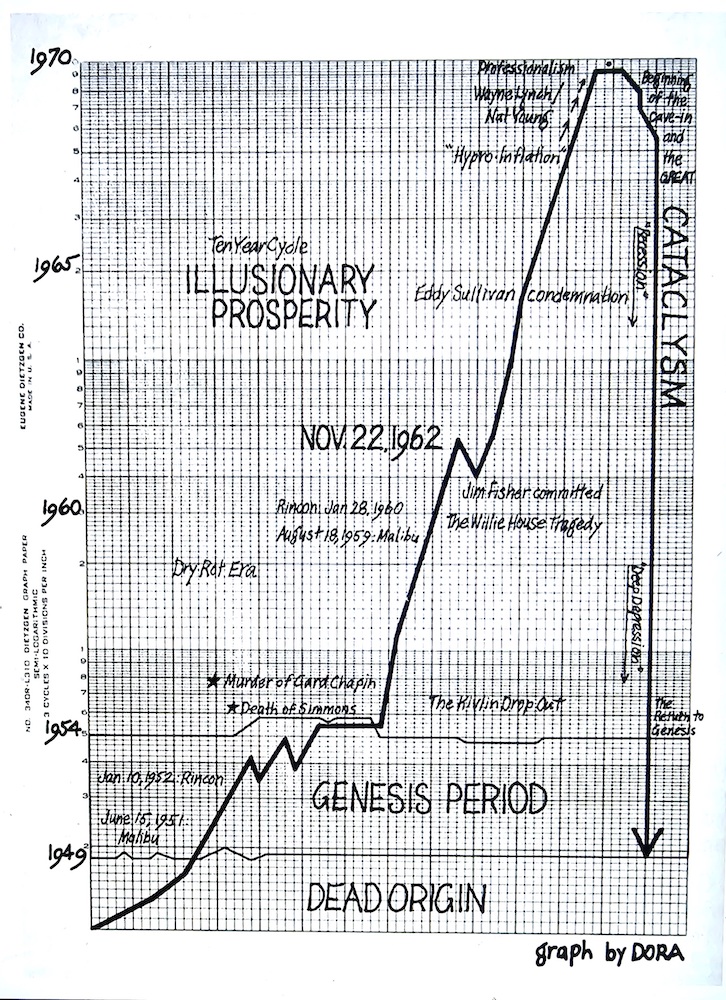

By the mid-fifties, Dora, Dewey Weber, Mike Doyle, and Mickey Muñoz were tanned royalty on the mellow sands of Malibu, and were inadvertently helping to manufacture, in their language and lives and habits, what would become a branded American totem – the California surfer. When surfing drifted onto the commodifying pop culture radar, the machine reached in with its Midas mitts and began selling it wholesale. So began the cataclysm. Dora, already a churlish and difficult figure in Malibu, railed in earnest as the beaches began filling up with arrivistes. He craved only alone time on the water. In the wake of surfing’s discovery by the untanned suburbs, the crowds would steal from Miki the only thing that actually mattered to him.

When fledgling songwriter Brian Wilson wondered aloud what he should write about, little brother Dennis (the only Beach Boy who actually surfed) suggested writing a song about the newish youth craze then beginning to redefine the beach. Sandra Dee’s breakout film Gidget of ’59 (based on real-life surf waif Kathy Kohner as memorialized by her novelist father) was likewise an early accelerant of surf-life’s OG endgame. In an extraordinary turn, Dora acceded to working on the Gidget set as a stand-in for James Darren’s character “Moondoggie,” Miki reportedly taking the opportunity to taunt and hector the film crew and otherwise all but sabotage the project with mild subterfuge.

Having charmed and scammed his way to a life enviably lacking a 9 to 5, Dora briefly saw the movies as a possible new means to finance his broader search for solitude and the perfect undiscovered shoreline. His “surf-flick extra” credits include Bikini Beach (1964), Beach Blanket Bingo (1965), and the classic How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1965). Ultimately, Dora’s utter inability to play the game would close that door and nail it shut. He reportedly met with studio heads on exactly one occasion to discuss a career in the burgeoning popcorn-surf canon, but within a couple minutes his scorn got the better of him and the meeting came to a quick conclusion.

As the curtain continued to fall, Dora signed up to compete in the 1967 Malibu Invitational surf contest, just the thing he abhorred. People in the know wondered at the change in him. In the event, he slid masterfully down the front of a wave, dropped his trunks and mooned the judges. It was an early farewell.

On the Lam

Dora’s endless search for non-trad, lifestyle-funding income would lead him to extremes – initially manifesting at the various ‘60s parties to which he would invite himself. Reportedly keeping several species of party garb and an ice bucket in his car, Dora would pull up in front of a place, scope out the dress code, brazenly don party-appropriate duds right there on the street, drop some cubes into a highball glass and walk in with his empty hoisted in greeting. Powerfully charming when he wanted to be (and a passable Cary Grant-type when cleaned up and suitably attired), he would dance and drink and gab, slipping away at the go-go height of the melee to rummage through the coats, wallets, and purses typically piled in a shadowy back bedroom. Years later, in the throes of misbegotten legend, Dora would tell an interviewer he had no real talent but living the way he wanted. In practice this bumpy inertia would have consequences Miki Dora would not ultimately outrun.

In 1973 Dora was busted for buying ski equipment with a bad check. Over the following year and a half, the wheels of justice would turn without Dora’s explicit participation. As the court’s officers pored over the charges, Dora skipped bail, his probation officer, the case, and the country.

From New Zealand, to Australia, to Biarritz, France, Dora kept moving – extracting funds from passersby, altering credit cards, and gaming the system as needed. In ’81 the French caught up with him and threw him in jail. At the end of the line, Dora agreed to return to the States to face the music, and once home his serial indiscretions would aggregate into jail time in L.A. County, Mono County, and in Lompoc’s federal prison.

The reckoning stripped from Malibu’s once and future king the last vestiges of his magnetic energy. When he was finally free of his obligation to remain in California, a spent Miki Dora headed back to Guethary, France where, despite an abrupt diagnosis of inoperable cancer, the great Miki Dora continued to hit the waves, but with increasing difficulty. In time, he was offered a first-class ticket home and fell into the arms of his father.

In 1949, the 15-year-old longboard wonder with the mischievous gap-toothed smile had everyone talking at San Onofre. Miki later made a fiefdom of Malibu before scrambling abroad to desperately seek his place in the world. When Miki Dora finally found his place, it was at his dad’s home in Montecito, where Dora passed in 2002. A photo in the house of a four-year-old Miki and his young émigré dad, taken some 63 years before, reportedly showed the two standing on a beach together, squinting in sunlight, the future yet to be written.

You must be logged in to post a comment.