The Women

A Jew and a Palestinian – women, of course – embrace in an otherwise nondescript conference room in UCSB’s Humanities Building. This is not a gesture, not a ceremonial cue for a Special Effect Peace to flood the room like a digital sunrise, not a performative, choreographed moment ablaze with Symbol. Dorit Cypis and Rula Awwad-Rafferty are simply greeting each other. Yes, they have their differences, as do we all. Does the historic scale and backdrop of the disagreement make it fatally insurmountable? Nope. That’s entirely up to them and they have chosen. The ballyhooed steamroller of history has no agency here. We aren’t subservient to it, as they are about to demonstrate.

This afternoon, Dorit Cypis and Rula Awwad-Rafferty will introduce us to their families and their stories. Their amiable but pointed dialogue will transcend and belittle the loudmouth institutions whose pronouncements are made in grander settings to lesser effect.

Jazz

The organizer of the event is Jeffrey Stewart – UCSB Black Studies Professor, Pulitzer and National Book Award Winner, recent electee into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and (significantly) jazz fiend. An uncommonly approachable giant – of Letters and otherwise – Dr. Stewart makes for the dais with the shambling gait familiar to some.

“I want to get started with this L2OVE event,” he says of the program, an initiative of UCSB’s DEI office. L2OVE is both an acronym and, in its noun form, the initiative’s propellant. “I first want to acknowledge and thank the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center’s director, Susan Derwin, and Associate Director, Christoffer Bovbjerg, for hosting and making the McCune Conference Room available for the event. L2OVE; Listening 2 Others Valuing Everyone,” Stewart explains. “This is something of a gesture on my part to counteract the level of silence on one hand and then yelling and screaming on the other, which seems to be characteristic of a lot of discourse these days on a variety of issues.”

Dr. Stewart elevates the proposition of West Indian poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant: to consent not to be a single being. “It’s very important to avoid the obsessive oneness,” Stewart says. “This event is not coming out of a political mentality, or any kind of arrogance that we can resolve problems. This is not a debate. How do we begin to listen to one another and value everyone?”

Rula

Rula Awwad-Rafferty is a professor of Interior Architecture and Design at the University of Idaho, and Chair of the Department of Design and Environments there. As she speaks, images on a large screen behind her accompany her reflections. Hers is the story of her mother’s family and ancestry and home – the village of Qula.

“I was born in Palestine, and I came here to the United States to study. Of all places in the world, I think California has the climate I was most used to, but I ended up in Idaho. So I am the oldest of seven kids, and I know my words, my thoughts, have meaning. I just speak to you today from my heart and I hope some of those words might translate, or might convey stories from my parents, grandparents, and others.

“My mother was born in Qula, her father’s family place and home – and one of the erased villages of 1947. My father is from Tulkarem, but would visit his aunt in Qula, so his memories of the place as a child guided me to find its ruins when I participated in my Fulbright trip.”

The destruction of Qula (and hundreds of other villages) took place during what the Palestinians call the Nakba – the catastrophe – when in 1948 the UK withdrew from its near-thirty year mandate over Palestine and the forces on the ground fought in the ensuing vacuum. In the event, the armored Alexandroni Brigade depopulated and destroyed Qula, adding to the flood of Palestinian refugees.

“My mother’s family were one of the lucky ones in the mass exodus. When they walked, they walked north and east. If they’d walked in the other direction I don’t know what would have happened.” Rula relates the harrowing story of her infant mother.

“That night in Qula, with literally minutes to spare, my grandfather and grandmother talked and wondered if my one-year-old mother would even survive the arduous flight that they were about to undertake in the darkness of night, and decided they would leave her protected in the courtyard. My grandfather said, ‘No one could hurt a child’. A few hours later, though, my grandfather’s heart would not let him leave my mother. He ran back the several miles to Qula, picked her up, and rejoined the rest of the family in their flight.”

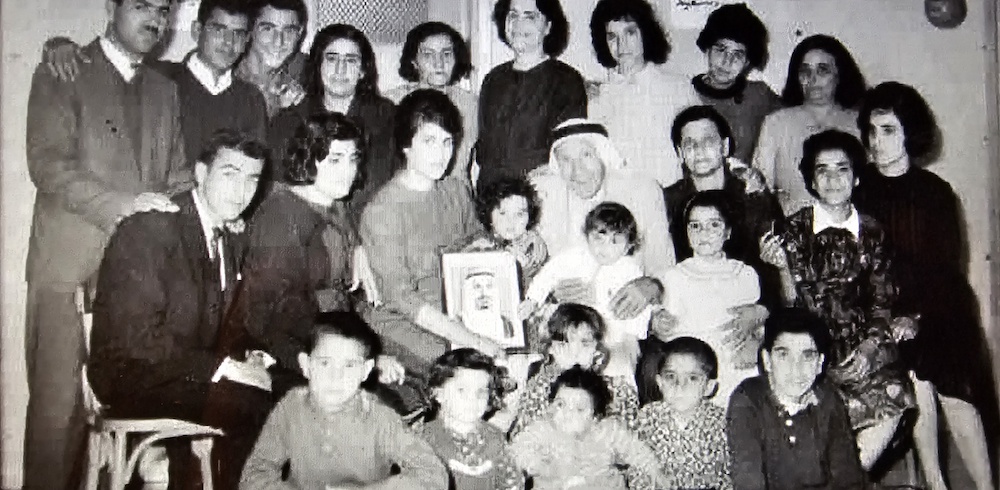

A black and white photo of a large, happy family appears on the screen. “That’s her father. He always wore his kind smile and the traditional Palestinian dimayh. And that’s her little sister, and that’s my mother. These are my memories.” She describes her family’s life outside Palestine. ”When the British divided the area, their 1917 Balfour Declaration gave the 1947 borders to establish a Jewish homeland, and the rest was the Palestinian area.

“And then in the 1967 war, much of that Palestinian land was lost and Israel occupied the rest of it. And so Palestinian people escaped once again with their house keys thinking ‘we will come back tomorrow’. I remember in 1967 my father was teaching in Saudi, we were with him, and we were coming back home. But all of a sudden the airports were closed. We couldn’t get back home. And I remember we ended up in Amman, Jordan, and my cousins were spread all over the world after this. In Arabic this is called al-shatat – it is the Palestinian diaspora.

“When we lived in Saudi, our accents, our dialects are very different. And I remember pretending to say words in the Saudi dialect and not getting it right, but trying just to fit in. Fitting in was always difficult – the trauma that actually lived with us to go to a place and not find our home. I think of that today as I see what is happening.

Culture resides in us; in the foods that we eat, in the traditions we carry, and all of these rituals. Those are the things that we carry with us. And this is my childhood story. Of course my friend Dorit is going to share her childhood story.”

Dorit

Dorit Cypis is an educator, a Pepperdine-trained mediator, and an artist whose work has appeared at the Whitney, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal, Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, LACMA, and many other places. The historical facts underwriting Dorit’s story are verifiable.

She places a hand over her heart and says, “I’m so moved by your pictures of ancestry, Rula!” She addresses the room’s small audience. “My family was extinguished in 1942 and 1943. My father was the only survivor of his family, and he ran for three years with the underground. He arrived in Palestine in ’41.” She indicates the screen behind her.

“This is my grandfather on my mother’s side, from Warsaw. He took the family out of Warsaw because Nazism was already a normal condition in 1933. It didn’t just start in 1939.” On the screen is a black and white photo of a man in trousers, cap, and work shirt. He’s on a hilltop and pointing into the distance. “Here he is standing on one of the Judean hills between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem,” Dorit says. “This is in the late thirties or early forties. He built one of the first cement factories in Israel.” She slows her speaking for emphasis. “He’s someone who sees open landscape as possibility, as a way to expand and to build, right? But what he’s also pointing to, if you look – it’s a very foggy little picture, very hard to see. There are settlements everywhere in the landscape he’s pointing to. They’re Palestinian settlements, right? It’s not an empty landscape.

“I was born in Tel Aviv Israel in 1951. I’m a first-generation Israeli, born three years after the creation of the nation. A hundred percent of the Jewish people that were refugees were in absolute trauma. They were the ones that survived the Holocaust. You don’t just move to another country and let go of your immediate emotional experience and create community.

So every Jew came from a culture escaping, of necessity, to Israel. This meant that all of a sudden we had to live together. That’s not an easy proposition. Just because you’re all Jewish doesn’t mean that you’re going to get along.

In the 1950s, my education as a first-generation Israeli was that we were told to let go of our cultural background, let go of our ethnicities and merge into one big category called Jewish Israeli. It negated centuries of rich cultural difference. It had to. Look at it politically, sociologically – the country needed to create a hegemony, to develop a voice, an identity, a unified language, a unified position in the world. So there were reasons for it, but there were many things lost in having done that.”

So what I’m feeling now in this moment – where everything is exploding and Jewish identity, all of a sudden, is challenged…” Dorit pauses. “Theodor Herzl is the visionary and the framer of Zionism in the late 1800s, he was calling Jews to leave eastern Europe because the pogroms” – organized massacres of European Jews – “were happening in Ukraine, in Hungary, in a lot of the eastern European countries. We had to leave.

“Herzl took a verse from the Old Testament,” Dorit says. “The voice of God said to them, do not worry. I’ll show you a land for a people without a land. But Herzl took that verse and he added three words to it. I’ll show you a land without people, for people without a land.” Dorit pauses again. “It was marketed from the beginning, from the late 1800s, as don’t worry, there’s nobody here. Jews and Palestinians were often manipulated by political forces,” she says. Her nuanced perspective has come at a cost.

“One thing I recognize between us,” she says to Rula, “is I don’t think you and I are typical. Most of my family won’t speak to me, and it’s very painful. Not that there shouldn’t be a Jewish nation, but how is it designed? Who has it taken from?” Dorit turns again to Rula. “We need to respect that. I acknowledge that you look like my family. I see your family, and I see my family.”

Willful Millions

Dorit and Rula of course bookended their conversation in another simple embrace. Our individual lives aren’t molded by “fate”, neither by our besuited, useless consuls. History has no agency. Its seeming inertia can be robbed of its phony inevitability by the willful millions of thinking, feeling individuals and families who do have agency. Yet history’s inanimate shadow guides and cows our inept and shameless “leaders” on all sides as they numbly abet catastrophe. Without fanfare, Rula and Dorit have eclipsed history. It’s a very big deal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.