Coffee with a Black Guy, Room for Cream.

James Joyce Answers the Tough Questions

It’s a singular scene.

In a spacious, unfurnished room aglow with natural light, James Joyce III is holding court, pacing before a vibrant orange wall whose only adornment is the framed photo of a swami. Several dozen yoga practitioners in shorts and tees sit before Joyce on a blond, hardwood floor, their numbers radiating outward in a series of semicircles. The vibe is Modern Socratic. The gathered are poised on pastel-colored yoga pads and cushions, bolt upright on their haunches and perpendicular with attentiveness. All eyes are on Mr. Joyce as he offers sage advice on purchasing a car, specifically on how to choose the safest make and model – though not exactly in accord with the Ralph Nader checklist.

“What’s the safest car for me to get?” Joyce asks rhetorically.

Lanky and relaxed in a black t-shirt and jeans, he’s letting stuff sink in. “Not in terms of rollover, or survivability in a crash. What car is safest… for me? What car can I drive that is least likely to get me pulled over?” The yoga crowd rustles and murmurs.

“What car is least likely to draw attention to me so law enforcement doesn’t think ‘…hmm. Let’s go check this out.’”

He lets the question hang before ticking off the points on his fingers. “Well, I’m not going to get anything exotic. I’m not going to drive anything too expensive. I am definitely not going to buy a Tesla.”

Here and there uneasy smiles of comprehension blossom in the gallery and are quickly tamped.

“I drive a white Toyota Avalon,” James says. “It’s my second one.

Holding the Position

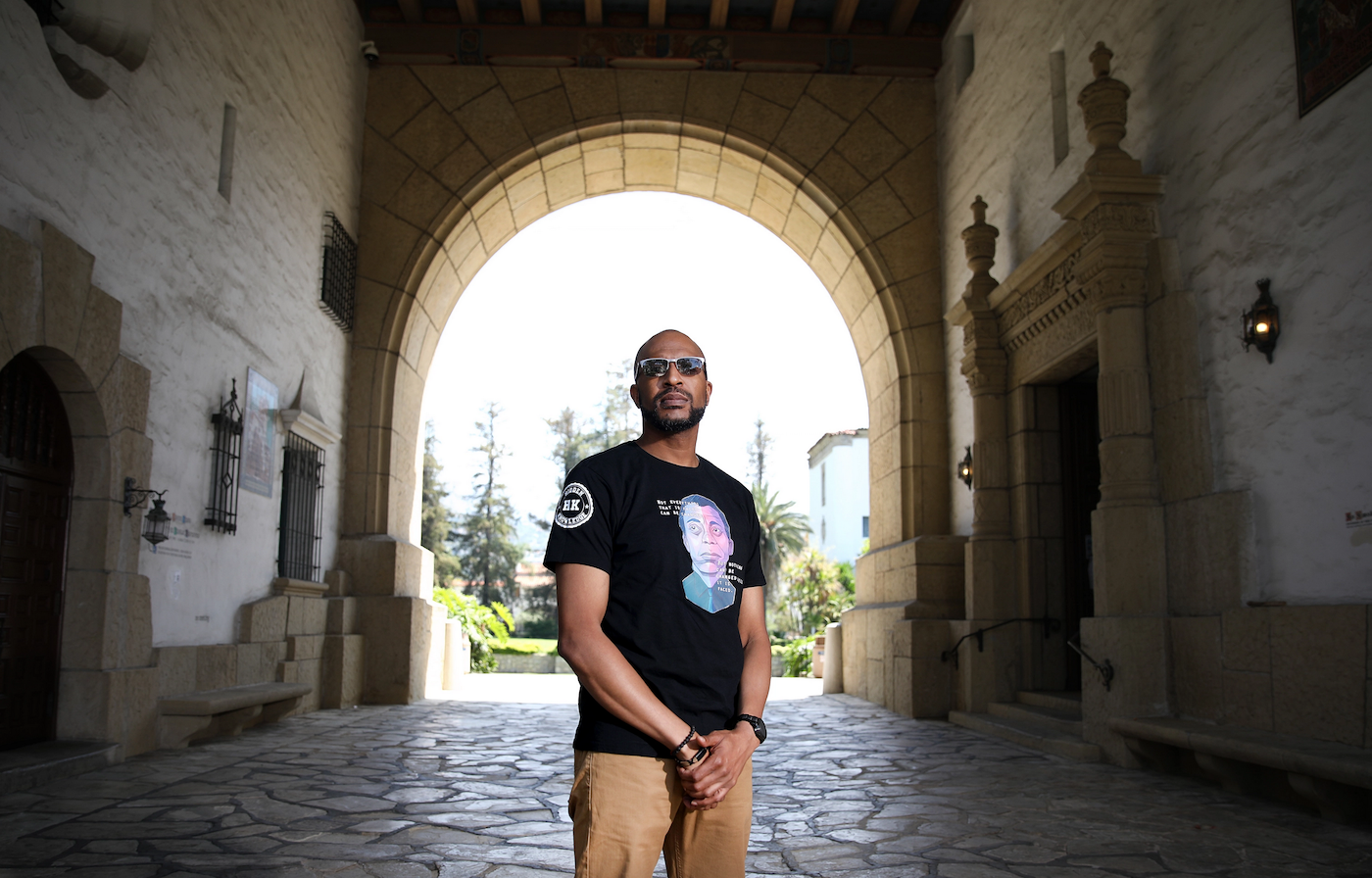

James Joyce III is a Maryland native and former journalist who has served as District Director for State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson for nearly eight years. The latter may explain his Civics 101 tone when summarizing Coffee with a Black Guy (CWABG) – an “authentic and genuine community-building” mission that essentially puts Joyce in a room taking questions from the racially inquisitive. The idea for the social impact gig spiked like a fever in Joyce following the back-to-back killings of Alton Sterling in Louisiana and Philando Castile in Minnesota in early July, 2016. The two police shootings owned the news cycles and turned the heat up on a national conversation that’s currently at full boil. That summer, though, all Joyce sensed on the streets of his adoptive Santa Barbara was a hermetically sealed insularity, Pollyanna in a ziploc.

“Respectability politics stops us from engaging truthfully. Racial conversations just don’t happen,” Joyce says.

The summer of 2016 wore on and the Maryland transplant walked local streets in a morose daze. Hamstrung and frustrated, he realized that making himself available to the interrogations of white Santa Barbarans was the quickest route to the catalytic pot stirring that might shake things loose. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the full-frontal, ‘ask-me-anything’ format of Coffee with a Black Guy was slow to take hold. “There were seven people at that first meeting,” James says without blinking. “It was an intimate conversation.”

Over time, and eventually fueled by such allies and sponsors as Pacifica Graduate Institute Alumni Association, Santa Barbara City College Foundation, Lois & Walter Capps Project sponsorships, Wealth Management Strategies, and LinkedIn Black Inclusion Group, CWABG found its feet and its jittery, willing audience.

James draws an unlikely analogy from the session at Santa Barbara’s Yoga Soup. “I’m a former hurdler, I’m flexible. I’ve done some yoga. Folks trying a new yoga position – it’s very uncomfortable. They can’t hold the position and they start shaking and then they fall out of it.” His brows furrow and he grins slightly. “But you get better the longer you practice, the longer you breathe and focus! Your level of comfort in the position is the measure of your development. That’s the same thing with conversations about race.”

Conversations About Race

The gallery rustles politely in their seats. Sunlight pours in through a wall of glass as A Tribe Called Quest’s “We the People” pours in from stereo speakers. James Joyce III comes on in business casual – grey slacks and a white button-up shirt. A married, gay, white gentleman relates a story of his Black husband being infantilized by a Macy’s clerk.

Joyce is gently adamant. “When you see racism call it out, right there. It doesn’t have to be confrontational. Just ask the clerk, ‘Excuse me… why are you talking to me?! He asked the question!’” – CWABG – February 28, 2019, The Sandbox co-working nexus in Santa Barbara.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but between the years 1525 and 1866, some 12.5 million Africans were kidnapped from their homes and spirited away to a labor-starved New World whose towering fortunes would be built on their lacerated backs. In the U.S. this murderous, liberty-mocking foundation story forms the substrate of a seemingly intractable misery. The inflammatory and cumulative police murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd in 2020 provided a flashpoint of nationwide protest, a rattling paroxysm that may help compel the approach of a ragged national reckoning.

In the midst of the current fury, Joyce still sees unfiltered conversation as key to getting whites and Blacks to see and hear each other – and to stand down. “There’s just that interpersonal divide,” Joyce says. “You sit down and it’s very difficult to hate somebody when you’re face-to-face with them. When you’re right there with somebody, and you do hate them – you know, it’s an invite to look them in the eye and explain what it is that you hate.”

Joyce’s hope – and increasingly the focus of his efforts – is that CWABG gains an exportable momentum that takes it to other communities. “Ultimately the vision is for Black people across the country to do this in their communities, to sit down and say ‘look, I know this place. I know my home. I see what’s needed here and I can use this already established platform to get it started.’”

Tale of Two Cities

Westminster, Maryland is 30 minutes northwest of Baltimore. No connective tissue should be inferred. “When you think of Baltimore, you think of The Wire. You think of a Black city, and that’s true. But a 20-minute drive and you’re in another county and there is Klan activity.” Joyce describes a KKK gaggle gathering on a street corner about a block away from his 1998 high school graduation party in a neighboring town called Manchester. “I wanted to go engage them but got talked out of it, fortunately,” Joyce says.

Joyce’s ascent through boyhood in Westminster came with the usual chaos – hormonal bewilderment, maddening search for self; fitful discovery of life’s complex stew of joy, heartbreak and wonder. These barely navigable “rites of youth” are a warmish central feature of white culture and literature. For Black kids in the U.S., self-discovery comes bundled with the dawning, grotesque realization that Blackness is an irremovable scarlet letter that soon invites a mysterious and spirit-breaking calumny.

“In elementary school I’d be the only Black kid in the class. They start bringing up slavery and everybody would turn around to look at me,” says James. He remembers the time in second grade when he had finished a quiz early, unlaced his shoes, and in quietude was toying with the laces on his desk. The teacher asked him to put them away and when he didn’t immediately comply, she remonstrated by wrapping them around his neck.

In junior high, Joyce and some friends swung into the local boot store, wanting to look at the latest Timberland boots. “Timberlands were big at the time in Maryland,” Joyce explains. Instead of retrieving shoes from the stockroom, the proprietor produced a gun and slammed it on the counter. “I don’t have any goddamned Timberlands,” he informed his young customers, who sprinted out in a mad scramble of gangly teen limbs.

Joyce’s mom – an ironclad social worker – got wind of the episode a couple weeks later and the incident made the local paper. The town’s mayor called the kids back to the store to receive their apology from the owner, who whined, “Aww, it was only a toy gun!”

QWERTY: The Passport

In middle school, a paper Joyce had written was singled out for praise by his teacher, “…one of maybe three male teachers that I’d had in my educational experience to that point,” says Joyce, who produces the actual essay with teacher comments, an item he’s preserved like a talisman. “It was a research paper.”

The teacher would later pull Joyce aside. Had he ever considered journalism? “I didn’t even know what the word was at that time. But he explained to me how it paralleled what I had already done, and that I just seemed to have this natural knack.”

In the summer of ‘96, Joyce took a Dow Jones journalism internship in Washington, D.C., spending time in historically rich academic environs surrounded by recognizable mentors. “We spent two weeks on the Howard University campus being taught by professional journalists,” Joyce says. “We went to USA Today and did a workshop newspaper there. This was when they had great programs to try to get minorities into journalism.”

As happens when young people are thrown into a controlled preview of the wider world, the lid was lifted. “Being a sixteen-year-old kid in D.C., feeling the freedom of just living, being on a college campus, and navigating this potential professional world…” Joyce’s voice trails.

Ohio University at Athens and the storied Scripps School of Journalism landed Joyce a newsroom internship at the Ventura County Star. Thereafter, he followed newspaper work to Indiana, Washington State, and Ohio, his last two beats as an education reporter – a role whose “just the facts” nature began to frustrate.

“As education reporter, I’m sitting there reporting on some dispute with the teachers’ union. I’m reporting the story – what the facts are – but I’m thinking ‘I could solve this! This person just needs to sit down and talk to that person!’ I mean, it can be that simple,” Joyce says with some exasperation. “But of course my job was to report, not to make recommendations. So I was sometimes conflicted in journalism. But nearly every city I parachuted into, one of my first stops would be the local NAACP chapter. That ultimately added to my reporting – an extra perspective I could utilize.”

The career arc brought Joyce back to the Golden State. “I ended up back in California and living in Oxnard, and that’s how I started working for Das Williams (as Field Representative/Communications Coordinator). When Hannah-Beth got elected to the state senate, her relationship with Das had her reaching out to me and asking if I’d be interested in working for her. I moved up to Santa Barbara.”

His career aside, what keeps Joyce rooted here in SB with its statistically tiny Black community and comparative insularity? “Economics alone should actually be pushing me out. I’ve had about a 66-percent increase in rent over nearly eight years living in town in the same place,” says Joyce, acknowledging the soaring housing costs that make livability difficult for many in this region. Even so, “After moving every couple of years for most of my life, I guess the cost-benefit of moving again hasn’t quite tipped me towards action.”

Besides, he says, “Santa Barbara is a great petri dish for CWABG.”

Coffee with a Black Guy

A young lady in the audience self-identifies as being of mixed race, and is speaking off camera. “When I talk about anti-racism with white people, it causes them to contract. They’re all ‘No, no – we don’t need anything anti. We want love and peace.’” The speaker pauses. “The heart of anti-racism is love and peace!”

James thanks her for her comment, and quickly drills down to the bedrock. “The fact is,” he says, “if you are not being anti-racist in America, you are being racist.”– CWABG September 7, 2019, Impact Hub, State Street in Santa Barbara

Across the country, protests and countervailing law enforcement measures seem to be bearing out, in sharp relief, the very grievances that are driving them. Is it possible a swords-into-plowshares moment can rise from this stark divide, one which forums such as CWABG help summon?

Henry O. Ventura, Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Employment Opportunity Manager for the County of Santa Barbara, thinks CWABG can at least be a bridge. “Coffee with a Black Guy is a very embracing and collaborative approach that creates a safe environment for people to ask what they have never dared to ask. The simple idea,” Ventura says, “is that we don’t know what it’s like to be somebody else. It’s a labyrinth. We just have to find our way through it together.”

Reverend Charles A. Reed, Sr. (“most people call me Pastor Chuk, or Brother Chuk”) sees the necessity and the boldness of Joyce’s mission. “What James is doing is sixty, seventy, eighty years past due,” he says. “Look, I know what it’s like to be profiled and beaten and thrown in jail, and I’ve also worked with law enforcement. There are questions people want to ask, but feel they can’t. I wish we had more young men like James. Men bold enough to step out on that platform.” Pastor Reed pauses and grins. “James is the kind of man you want to be your son, or marry your daughter.”

The challenge in Santa Barbara, where the Black population as of 2020 has declined to 1.3%, could be seen as Everest-like to a guy bent on talking race with the locals. But Ahmaud Arbery had simply gone out for a jog. In the wee hours in Louisville a commotion outside Breonna’s apartment door prompted her – as it would anybody – to querulously cry out “…who is it?” before a battering ram answered and the shooting began. George Floyd bought some cigarettes and ended the afternoon with another guy’s knee on his neck, a living dictionary illustration of the word subjugation – the killer’s hand draped in his pants pocket like a guy waiting for a bus.

Disenfranchisement by birth is glaringly anti-American; a toxic breach of the E pluribus unum compact we learn about in grade school. Institutionalized racism is as ruinously anti-American as any of the other threats that have convulsed and focused the country over the past century. It needs to be met as forcefully, one conversation at a time.

“I always remember walking home from school through town, maybe a mile. Walking past people and they’re locking their car doors as you get closer.” Joyce pauses and looks slightly away. “Being a kid, learning your identity, then taking your pencil eraser and trying to rub off your Blackness. That’s some shit that we did. It’s painful.”

James Joyce III, a Black guy from Westminster, Maryland – a journalist and communicator – is parlaying his life experience and skill sets into difficult conversation whose significance can’t be overstated at this moment. He wants to make an appointment with you, with your group. Go ahead and drop him a line. Cwabg.com.