Oil Platforms’ Removal?: Reefing the Superior Environmental Option

Reaching the end of their economic oil producing lifetimes, many of California’s and specifically Santa Barbara’s offshore platforms are in the process of being decommissioned. They can either be fully removed and taken to scrap yards on land, or they can be turned into state-managed artificial reefs through California’s Marine Resources Legacy Act. Why wouldn’t one take advantage of the marine habitat inadvertently created by our dormant oil platforms?

On December 7, 2023, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) issued a Record of Decision (ROD) recommending the full removal of California’s 23 offshore oil platforms in federal waters, following a Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS) conducted to assess decommissioning options for platforms, pipelines, and other related infrastructure. However, upon close review, the PEIS and ROD appear to have reached misguided and detrimental conclusions due to critical oversights in their analyses.

Most glaringly, the ROD bizarrely recommends full removal while also finding that partial removal and conversion of platforms into artificial reefs is actually the “environmentally preferable alternative.” The ROD justification for still pushing full removal cites “long-term risks” like entanglement and hazardous material leaching. But evidence suggests these risks can be safely managed, and regardless, they pale in comparison to the enormous environmental benefits of partial removal and reefing. Not to mention the monumental carbon footprint of unnecessarily dismantling the oil platforms all the way down to the ocean floor.

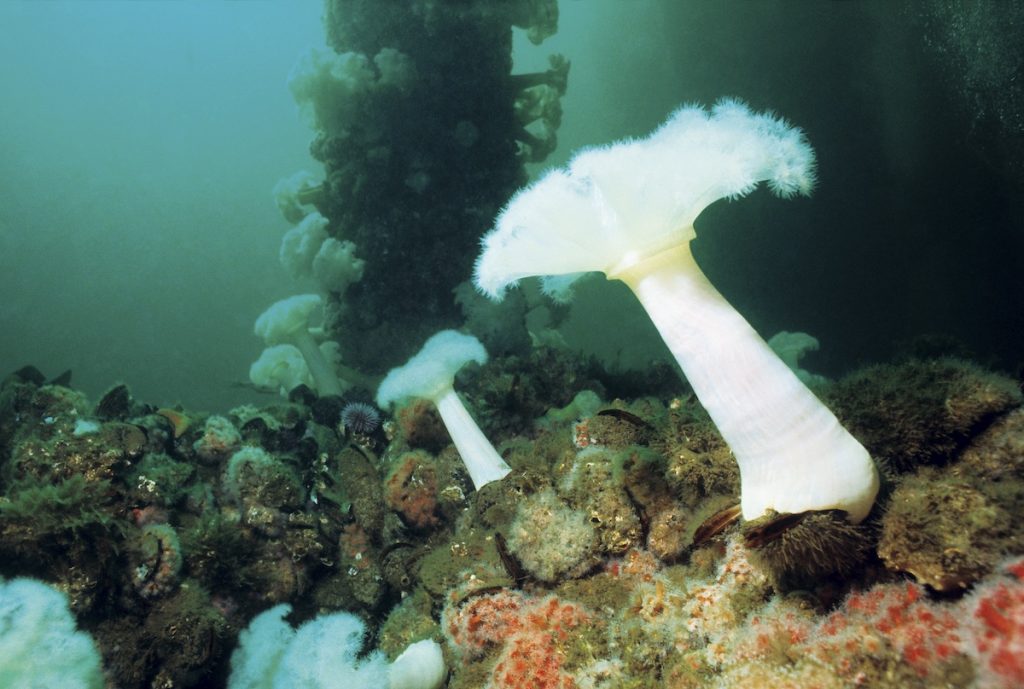

In the decades since their installations, the steel support structures of California’s offshore oil platforms, 19 of which sit in federal waters off Santa Barbara, have inadvertently become some of the most productive marine habitats on Earth. The support structures, referred to as “jackets,” which stand in anywhere between 100 feet and over 1,000 feet of water, are crusted in life from top to bottom. Mussels near the surface give way to anemones, nudibranchs, copepods, and associated communities of rockfish in deeper water.

The scale of the situation in California, however, is minor compared to the Gulf of Mexico where over 5,000 platforms have been both installed and removed. To date, over 570 have already been turned into artificial reefs managed by the states of Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi.

In California, only a few small platforms have been removed from state waters and none have yet been reefed. California’s platforms are the consideration of a federal Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS) for Oil & Gas Decommissioning Activities on the Pacific Outer Continental Shelf (POCS). The study is meant to be an overall, non-site-specific, analysis of environmental impact.

The PEIS looks at four alternative pathways for decommissioning – including full removal, two versions of partial removal, and the pursuit of no action at all. Under both full and partial removal, an oil platform’s oil-related infrastructure would be decommissioned and its topside structure removed. There’d be nothing left to see above water.

With full removal (“Alternative 1”), the remaining submerged platform jacket would be severed from the ocean floor using mechanical and abrasive cutting tools or, more likely, explosives and taken to shore for disposal and recycling.

The two versions of partial removal would see the jacket cut 85 feet below the ocean surface and the lower portion either left in place or towed to an approved reefing site where it would become a state-managed artificial reef. The upper jacket, the first 85 feet severed, would then either be taken to shore for disposal (“Alternative 2”) or placed alongside the rest of the structure in the water where it too would live on as an artificial reef (“Alternative 3”).

Finally, platforms could be left in place on the Santa Barbara horizon (“Alternative 4”).

The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) says they reviewed these alternatives but ultimately decided on recommending Alternative 1, full removal, as it is the alternative that best “ensures safe and environmentally sound decommissioning activities.” Yet, by their own calculations, they recognize that partial removal, specifically Alternative 2, is the “environmentally preferable alternative.” Something seems strange right out the gate.

However, upon reviewing the PEIS, it’s not surprising that the ROD yielded this result. The PEIS contains a few seemingly simple caveats and appears to be sorely lacking in its analysis. Let’s look through it.

The Numbers Not Being Considered

First, the PEIS’ carbon emissions estimates are extremely low. For some reason, the PEIS makes the decision to only consider “air emissions … that occur within the jurisdictions of the SBCAPCD, the VCAPCD, or the SCAQMD.” That’s to say Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles, and Orange County.

When looking into partial removal, this might yield an accurate number because removal of platform topsides could be accomplished in a much shorter period using smaller derrick barges with relatively low emissions.

Yet, to fully remove platform jackets of the larger structures, seven of which stand in depths greater than 600 feet, the employment of massive marine construction vessels not found on the West Coast would be necessary. Heavy-lift vessels and semi-submersible crane vessels, the largest marine vessels in the world, are the standard for full platform removal in water depths exceeding 400 feet. According to studies from platform decommissioning specialists John Smith and Bob Byrd, full removal would require these vessels be mobilized from either the Gulf of Mexico, Southeast Asia, or the North Sea. Many of these heavy lift vessels and semi-submersible lift vessels are too large to pass through the Panama Canal requiring them to travel around the tip of South America. Furthermore, there are zero sites on the West Coast capable of processing the large volume of steel removed during a large platform decommissioning project, so it would have to be taken back to the Gulf or elsewhere for disposal and recycling. This would require the mobilization of a fleet of tugs and barges to transport the materials to the Gulf of Mexico through the Panama Canal. The emissions generated during this 5,300 nautical mile trip were also not considered in the PEIS.

The PEIS therefore is missing the single largest chunk of emissions. Which seems like a rather large omission.

The PEIS determines that the removal of Platform Harmony, the largest platform standing in 1,198 feet of water, would release the equivalent of 34,819 tons of CO2. Smith and Byrd’s 2021 study found that the removal of Platform Harvest from a comparably mere 675 feet of water would release the equivalent of 56,187 tons of CO2. That’s equivalent to consuming “nearly 120,000 barrels of oil … or providing electrical power to 8,600 homes annually.” Yikes.

As for partially removing Harmony, the PEIS says emissions would be the equivalent of 13,901 tons of CO2.

Furthermore, the PEIS’ choice of language in this section is discouraging. It concludes that full removal would result in “temporary and minor impacts on regional air quality” but says nothing about the negative consequences of releasing massive quantities of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Second, the PEIS concludes that full removal would cause “no more than moderate impacts” against marine fish and essential fish habitat. Their explanation states that “while potentially important locally, the loss of platform- and pipeline-related hard bottom habitat is unlikely to result in observable, long-term changes in marine invertebrate communities of the POCS.” This is true in one lens and false in another.

If we take total habitat area as our only metric of value, then no, California’s OCS platforms are not important. Viewed alongside California’s natural reefs, the area contributed by platforms does not factor significantly.

Yet, the ecological value and productivity of the habitats must not be overlooked. Bocaccio and cow cod rockfish are economically important in California and, while not technically endangered, are considered overfished. The verticality of California’s deepwater structures provides a unique habitat vital to raising juvenile rockfish. Each year, 20 percent of the juvenile bocaccio that survive across the species’ entire geographic range from Alaska to Baja, live in the depths beneath the platforms.

The platforms are so productive and contributory to robust marine life that a 2014 study from Jeremy T. Claisse of Cal Poly Pomona found them to be “the most productive marine habitats in the world per square meter.” Productive here as opposed to attractive, which would mean the platforms are becoming habitats for fish born elsewhere. California’s platforms are fantastic incubators and creators of life, not simple attractors. This is in part due to the fact that the platforms are not heavily fished. For the most part, they operate essentially as marine protected areas, working to repopulate California’s fish-depleted coastline.

Near Anacapa Island, Platform Gail stands in 739 feet of water. Removal of its 1.3-acre ecosystem would be equivalent to the destruction of 30.6 acres of average-producing Southern California cow cod habitat or 72.3 acres of Southern California bocaccio habitat.

All of this is not to mention the plethora of smaller lifeforms that would be killed if the platforms are removed. To some, they aren’t worth accounting for. “It depends on your philosophy,” said UCSB’s Dr. Milton Love in one of our conversations. “There are millions and millions of animals living on [these structures].”

The PEIS is not far off in its analysis here, but to say the platforms are only important locally minimizes their upside.

Third, the PEIS downplays the environmental impact of removing a platform’s shell mounds. As mussels and scallops die or are scraped off the upper legs of California’s oil platforms, their shells drop to the sea floor. There they have formed shell mounds, fused together by waste muds and cuttings from the oil drilling process. While providing complex, productive habitat, the shell mounds also trap dangerous hydrocarbon pollutants. They have been found not to be toxic to surrounding wildlife, but if disturbed, would release their drill-waste into the water column.

Under a scenario of full removal, shell mounds would be removed by dredging equipment. Partial removal would see them stay. The PEIS ascertains that the shell mounds are “non-hazardous waste”. Yet, according to Smith, this is misleading given the fact little is known about the composition of shell mounds as most of them have not been sampled or subjected to laboratory analysis. The PEIS is also misleading because the release of oil-based drilling muds and cuttings was not restricted until the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began issuing the National Pollution Discharge Elimination permits for the discharges in the late 1970s. The possibility therefore exists that deleterious hydrocarbon contaminants and other hazardous materials may be present in the shell mounds of older platforms, five of which were installed and began drilling oil and gas in the late 1960s.

According to Smith, in 1996, when Chevron removed four platforms (Chevron 4-H project) from California’s coastline, the shell mounds were left in place. Laboratory testing of shell mound cores detected elevated concentrations of metals associated with drilling muds (e.g., barium, chromium, lead, and zinc) as well as monocyclic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). In addition, PCBs were detected at concentrations up to 1.6 parts per million in the mounds. The EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers determined the shell mounds were not suitable for ocean disposal at approved offshore hazardous waste disposal sites based on the contaminants in the materials. It was too risky.

The best option seems to be to let the shell mounds remain in place, allowing them to denature over decades versus trying to completely remove them and risk dispersing contaminants in the marine environment.

If you’re beginning to notice a trend here, you’re on to something. The biggest problem with the PEIS lies at its foundation: the study judges the OCS’ platforms as a collective. Clearly, they each have vastly different circumstances. Some would be easy to fully remove while others would result in unnecessary and serious carbon emissions. Some provide extremely productive marine fish habitats, others less so. The removal of some risks releasing pollutants into the environment at a dangerous rate, while pursuing the same process at others wouldn’t be risky at all.

Luckily, the PEIS and ROD don’t directly decide anything. While some OCS platforms are still actively producing oil, many are shut-in. The ROD merely serves as a recommendation that will come into play in the next step of decommissioning: the preparation of environmental impact statements (EIS) for each individual platform upon their specific decommissioning. Those EISs will be far better at analyzing the environmental impacts of removing platforms than this PEIS could ever be. Hopefully they can remain objective following this premature and misinformed ROD recommendation.

The most befuddling point of all is the ultimate recommendation of BSEE’s ROD itself. The ROD recognizes partial removal, albeit not the version of it I would have expected, as the most environmentally friendly approach towards handling the OCS platforms’ decommissioning. The only reasoning BSEE gives for its choice not to recommend that direction is this:

“Alternative 2 leaves some infrastructure in place that may pose long-term risks to other uses on the OCS, including entanglement and loss of gear to commercial and recreational fishing and contaminant leaching from potential hazardous materials present in shell mounds remaining around the base of platforms.”

The first concerns should be a non-factor considering the safety precautions required and the long successful history of reefing in the Gulf of Mexico. The second is based on a misunderstanding and is more a risk in the full removal scenario than the partial. Even if we accept these reasons, are they enough to sacrifice the upside of leaving the platforms in place? We haven’t even considered the tens of millions of dollars per platform the State of California would receive as compensation in the event an Oil & Gas operator did decide to pursue reefing as an option. These funds would of course go towards developing a state artificial reef program and managing any reefed platforms.

I’m not saying all of California’s platforms should be reefed. Some of them probably shouldn’t. I’m just saying we should not close ourselves off to the possibility. BSEE declined to comment.

A final consideration: what about Alternative 4? For some OCS platforms, it might make the most sense to just leave them in place. May it not be best to leave a few platforms on the Santa Barbara horizon as reminders of the local history with oil? Ideas have been floated around with the goal of redeveloping platforms into sites of aquaculture, research, or wave energy production. What about putting a wind-turbine on a platform? Or even some use we aren’t yet aware of. Perhaps the OCS platforms can be adapted from bastions of extraction and environmental destruction to symbols of California’s commitment to the future and determination to learn from the past.