On the Job

For most of human history, the people who did the hardest physical work were at the bottom of the social scale. These were jobs that went to people called peasants, villeins, or slaves, working in the fields alongside horses and oxen. Women and their traditional roles of housekeeping and child-rearing were always in a class inferior to men. At the top were the landowners, who formed the major part of a hereditary Aristocracy.

Of course, there were exceptions – but this arrangement constituted a very stable social pyramid, which lasted through the centuries, and in some ways, in many parts of the world, is still with us today. However, a great change began to come about, some 300 years ago, together with what we call the Industrial Revolution, when ownership and control of machines, rather than of land, became a new standard of power, and revised the traditional notions of a social hierarchy. As a result, there emerged a new lower class of mostly poor urban workers. These people had virtually no voice in their own government, until the social cataclysm, known as the French Revolution, for a time, at least in France, unseated the ruling Aristocrats in a violent upheaval, as embodied in Paris by the guillotine.

But, as you know, most things in life, and in History, have a tendency to swing back, after hitting an extreme, and this happened in the Century after the French debacle, with the downtrodden masses again feeling downtrodden, and thus giving rise to new voices of protest and rebellion. Of these, the most remarkable was that of a German Jew named Karl Marx, who, together with a collaborator named Friedrich Engels, became the intellectual leader of a new movement based on the idea of empowering the Working Class to overthrow the system which kept them “in chains,” and seize control of the means of production for which they labored.

In 1848, they published a document called the “Communist Manifesto,” calling for the unification of all workers everywhere – a breathtaking concept at the time. The very words “Communist” and “Communism” were startlingly new. In time, as we know, they fostered a broadly international movement which captured the minds of millions and threatened established ruling systems around the world.

The idea took hold, in many societies, that a great cultural change was coming, which was generally referred to as “the Revolution.” “Comes the Revolution” was a stock phrase preceding speculation about what the Future would be like – but nobody was sure exactly when or where this momentous change would begin. There seemed to be wide agreement that it was most likely to happen in some part of the advanced Western world – perhaps in Germany or France, or even in the United States.

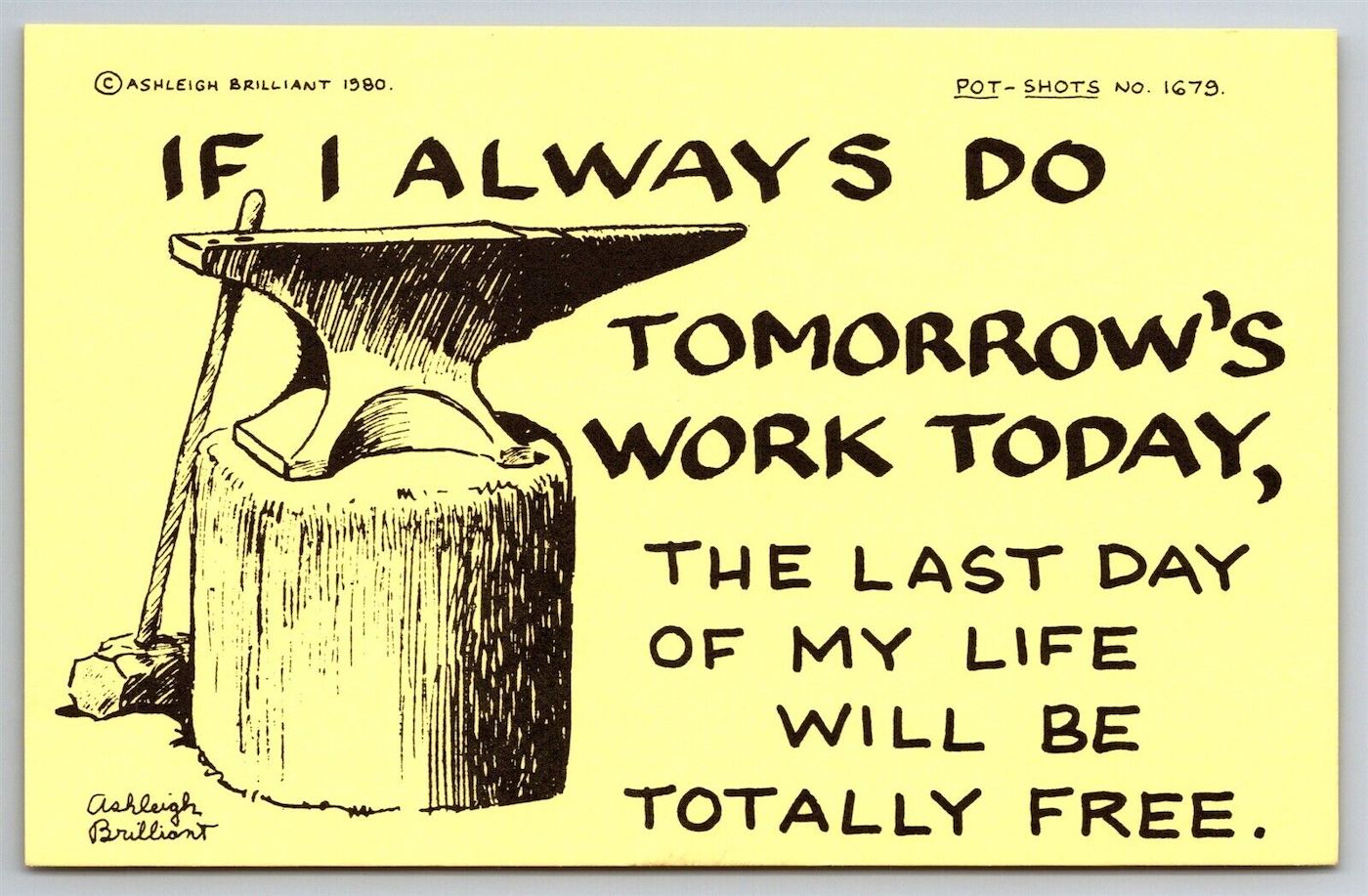

But, contrary to these expectations, when it did come, it was in one of the most politically and socially backward of all the “civilized” countries – the Empire of Russia. It was there, in the first two decades of the 20th Century, that the Communist Revolution, still flying the banner of Karl Marx, and using the symbol of the Hammer and Sickle, to represent workers both in Industry and in Agriculture, took hold, and an extreme left wing of the Movement, called the Bolsheviks, came to power. (Marx himself had been living quietly in England for many years before his death in 1883.)

In the process, the entire Russian ruling family was wiped out, to be replaced eventually by a man named Lenin. All this took place against a background of the First World War, which engendered turmoil and tumultuous change all across Europe. The new Russian nation which emerged used the term “Soviet” which had been applied to a system of workers’ councils, to call itself the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) or more commonly the Soviet Union, a political entity which survived for some 70 years, before being more or less peacefully dissolved in 1991.

Meanwhile in other countries, particularly the U.S., the spread of Communism had been seen as a great threat, and at least twice – in the years after both World Wars – this fear had mounted to a panic, creating each time a “Red Scare,” that dominated national attention for many months, until it subsided in a wave of apathy. But Labor had become so accepted as a political force that in Britain it was now the name of one of the major Parties. The workers of the world had indeed come a long way.