Wear and Tear

Over time, it seems that everything wears out, even – or especially – our own bodies and minds. But many things that once seemed irreparable or irreplaceable – can now indeed be repaired or replaced.

With regard to ourselves, the whole concept is relatively recent – not counting the story that Eve was made from a rib of Adam. Of course, our bodies have always had what in some ways seem miraculous means of repairing themselves, through a process called “healing.” And even today, doctors understand that the practice of medicine is mainly a matter of helping the body to heal itself.

But, by being able to control infections, and use lenses to see what they are doing (plus the blessings of anesthesia), surgeons can now tinker with our parts with more access and more success than ever before. It may have been blood transfusions that started the ball rolling, but the terms “graft” and “transplant” which once were used only in dealing with the vegetable kingdom, now have wide application to the manipulation of our organs and our skeletal structure. And we have now crossed a once-inviolable line between the bodies of humans and those of other creatures, mainly other mammals. And although there is no competition between the different species to be chosen as “donors,” certain creatures, of whom, perhaps surprisingly, pigs are currently a favorite, have been found to be a particularly good source of certain body parts, such as heart valves.

Happily, most of us are less familiar with that kind of repair and replacement than we are with the wear and tear to which our automobiles are subject. The most common trouble, ever since pneumatic, or air-filled, tires began to be used, about 1895, right up to the present day, has been the “flat tire,” usually resulting from penetration by some object, allowing air to escape – a mishap so familiar that, in some countries – as I noticed in Israel – any unexpected interruption in plans is commonly referred to as a “puncture.”

But, as with our bodies, almost every part of a car, from brake-pads to windshield wipers, is subject to wearing out and breaking down – or (in the case of cars) to being so ruined, as in a serious accident or other vehicular trauma, that repairs would cost more than complete replacement. In such cases, the car is considered to be a total loss, which has led to a new verb in our language (though it is still considered slang): “to total,” meaning “to wreck,” or “utterly destroy.”

But it is not only automobiles that are subject to wear and tear, but also the roads they drive on. California was the first region of the world to become heavily motorized, and therefore the first to be aware of widespread road failure caused by motor vehicles. A road-building program had begun in 1912, when such vehicles were still relatively rare. But, ambitious as it was for its time, this plan was soon proven so inadequate that an engineering study only nine years later found that in the rebuilding of one old road, the builders destroyed, with their own trucks, more roads than they repaired.

There can also be unfortunate instances in which some vital part of a long-trusted man-made structure can, without advance notice, suddenly yield to the forces of gravity, or, to what engineers and architects categorize as “stresses and strains,” leading to sudden failure. Some dramatic examples of this kind of disaster are those of large important bridges, perhaps crowded with vehicles and people, suddenly giving way, plunging some of its occupants into whatever lies far below. Movie makers have long been fond of this kind of disaster, because it is so exciting and photogenic. Two very popular films on the theme of intentional bridge destruction have been For Whom the Bell Tolls, and The Bridge on the River Kwai.

But large buildings have also been known to collapse, though usually in countries where those under construction are not subject to as rigorous inspection by experts, as in more advanced parts of the developed world.

Of course, when it comes to this kind of deterioration, nothing can compete with Nature. Any geologist will tell you that every natural object on Earth is subject to the two countervailing forces of erosion and deposition. Like Love and Marriage, as the song says, you can’t have one without the other.

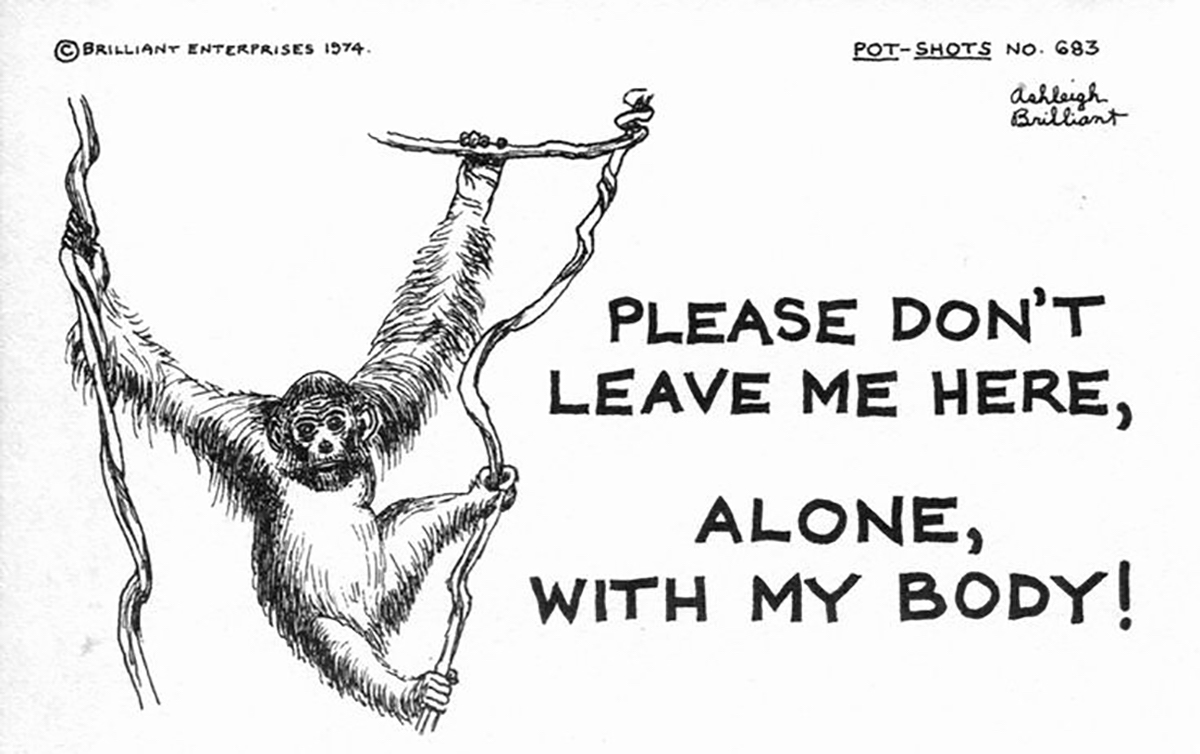

And, as I myself, have written,

“Nothing can wear you down more completely than life.”