Twilight at Bellosguardo

A late afternoon sun graced another lovely event at Bellosguardo on Thursday, September 21. That day, the Bellosguardo Foundation hosted a reception and book talk by Liz Brown, author of Twilight Man: Love and Ruin in the Shadows of Hollywood and the Clark Empire. As guests mingled and explored the estate, docents were on hand to explain the architecture, furnishings, and decorative elements of the beautiful rooms of the mansion. Outside, attendees were drawn to explore the gardens and take in the bluff views before returning for wine and appetizers and the soft strains of guitar music.

Bellosguardo was an appropriate venue for a talk by Brown, who is related by marriage to William A. Clark, Jr., founder of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra and the Hollywood Bowl. Her grandmother was a favored niece of Clark’s second wife, Alice McManus Medin, and spent a great deal of time with her aunt and uncle, who adored her.

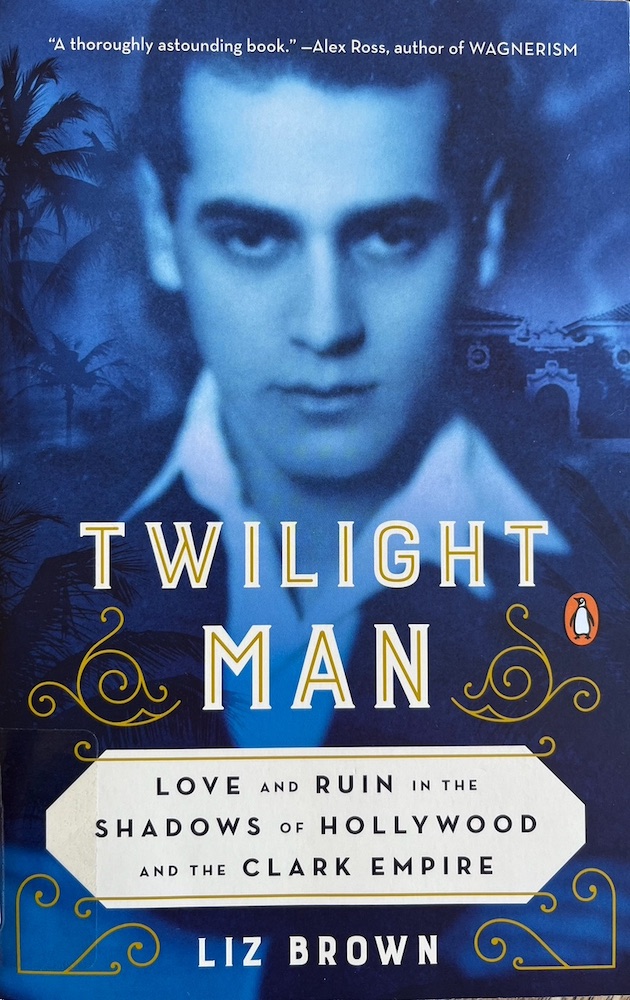

When Brown took to the dais in the fading light of the courtyard, she explained how the book had come about. After her grandmother (also named Alice) passed away, Brown discovered a photograph in a drawer. A Rudolph Valentino-like portrait stared intensely and seductively from its frame. The photo was inscribed, “for Alice McManus, With Sincere Good Wishes, Harrison Post, 1922.” Intrigued by the photo, Brown learned that Post had been a homosexual lover of William A. Clark, Jr. and had actually known her grandmother.

A few years later, the desire to know more about Post drove her to action, and Brown began a journey into the past to discover the story behind a boy named Albert Weis Harrison, who had reinvented himself as Harrison Post. In so doing, she also explored the inner character of William A. Clark, his son, Will, Jr., and the America in which they lived.

Brown’s ability to lyrically weave historical context into the story is one of the great strengths of her writing. She connects, for instance, the Clark fortune in copper mining in Butte, Montana, to the glamorously dissolute Hollywood where Post and Clark lived a gilded and illicit life.

“The copper had been clawed out of the earth and smelted,” she writes, “the arsenic and sulfur gone, never mind the poisons burned into the air and seeping into the water table. Now the purified metal sparked and the current jumped, arching from one carbon electrode to another. The key lights shone down on the kohl-eyed beauty collapsing in the lead’s muscled arms. The copper rushed the electricity through the projector’s motor, beaming the gorgeous people out through the curved lens across the dark room and onto the wide waiting screen.

“Outside the current sped through the lamps, flinging columns of light up to the night sky. The radiant stars stepped out of their gleaming chauffeured cars. They turned to the clamoring crowds, flashbulbs exploding. They smiled and they waved, their names glowing on the marquee above.”

“Will Clark might shrink from the camera,” continued Brown, “but not Harrison Post. In a photographer’s studio, his double-collared shirt open at the throat, he crossed his arms, lowered his head, dark eyes glowering, and nearly smiled when the shutter clicked.”

Brown’s exquisitely researched book traces Post’s life from childhood to an early death and from the East Coast to California, Nazi Prison Camps, and Mexico. It’s a fascinating and well-told tale. Twilight Man will soon be available from the Santa Barbara Historical Museum and is available online.