To Evacuate or Not to Evacuate?

I’m sure I’m not alone in being relieved that our community did not have to be evacuated during the storm this past weekend. Still, I was on pins and needles wondering whether that scary alarm would suddenly come blaring from my phone, informing me it was time to pile my family, my dogs, and a bag of necessities into my car and search for a safer place to wait out the storm. Luckily, it didn’t happen. But I thought, given how much we all dread being told to evacuate, that it might be helpful to ask Montecito Fire Chief Kevin Taylor, who was the Incident Commander during the 1/9 Debris Flow, to explain exactly what goes into deciding whether or not an evacuation order will be issued.

Needless to say, I found it a relief (though not a surprise) to learn that there was both hard science and social science behind these critical decisions; not just someone’s gut instinct or a divining rod, or tea leaves. I hope you find this as helpful as I did.

Kevin Taylor (KT): After receiving a whole bunch of input from community members, we know that we missed on messaging for the 1/9 Debris Flow. Because of that, we developed some internal processes so that we wouldn’t miss next time. These have been in place for all of the evacuations that we’ve done since 1/9/2018.

One important piece of this is how we determine whether or not a protective action order is given. There are three types of protective action orders: There is a shelter in place, an evacuation warning, and an evacuation order.

Any time there is a storm of significance, there is a group called the Storm Risk Decision Team that gets together. That group consists of the City of Santa Barbara, Montecito Fire, Carpinteria Fire, County Fire, and the Sheriff’s office. That meeting occurs at two o’clock every day because that’s when we have a very high-resolution weather forecast. It’s facilitated by OEM (Office of Emergency Management), and it opens with a forecaster from the National Weather Service, Los Angeles, giving us the forecast.

After that, a protective action recommendation is given, and then the Sheriff’s office either says yes or no. Because you’ll recall, in Santa Barbara County, the Sheriff’s office is the designated agency in county government code for determining if an evacuation or protective action order is issued. If that occurs, then we talk about how it’s going to be messaged and when it’s going to be messaged, if the EOC is going to be activated, if the incident management team’s going to be activated, and if there’s going to be an incident command post.

Gwyn Lurie (GL): What variables guide your decision making?

KT: All of our decision-making is guided by six principles: We will ensure public safety. We will evacuate only when necessary. We’ll evacuate only those areas necessary. It’ll be for the shortest time possible. We’ll return people home as soon as possible. And then probably most importantly, we’ll provide the community with clear, timely information, and rationale for the decision.

GL: Why was there a decision not to evacuate this past weekend?

KT: Because this event rose to the level of a weather advisory, not an evacuation. It was relatively mild compared to what we had last Monday. But we committed to the community that if there’s a storm coming, we will keep you informed. And so we want folks to be prepared because in Santa Barbara, front country, south-facing mountains, things change very rapidly.

GL: So, I assume you go into these meetings with an educated opinion about the outcome?

KT: Correct. I have a very intimate relationship with all the forecasters, and so I do my homework. I call them in advance, get the information that we need. We consider the forecast, the status of the debris basins, the status of the nets, and the status of the flood control channel. Specifically, the VARs, also known as choke points. Our staff inspects those every morning when there’s a storm. We get a report from flood control that shows us all of the flood control work that’s going on in the county right now.

GL: Is it correct that your recommendations consider flood control studies and historical documentation to find the most parallel historical situations by which to make your current decisions?

KT: Correct. And this is the scary part. Debris flow science is a very young science as a whole. The body of work is relatively small. The main event that people are studying right now is right in our backyard, the 1/9 event, 2018. There’s really good information about what happens one year and two years after a fire. There isn’t good information about what happens in year three, four, five, or even up until the next fire. That’s why this is the best, most accurate estimate of where catastrophic debris flow will occur in our community. And remember, catastrophic means that house right there gets picked up and washed to the Pacific. That’s the definition of catastrophic.

Click here to view the interactive Santa Barbara Disaster Map

KT: Last Monday, on 1/9/2023, we evacuated the entire community because there were so many unknowns … We messaged the community over and over again for three years, that if your property is identified as at risk in a storm on the “Interactive Map of Affected Properties” (found here: www.countyofsb.org/196/Maps), please be prepared to leave. And this map is so easy to use. It’s interactive. You just put in your address and it tells you if your house is at risk. That means your parcel is outlined in red. You don’t change that when the disaster strikes, you go back to it. It’s important to be consistent.

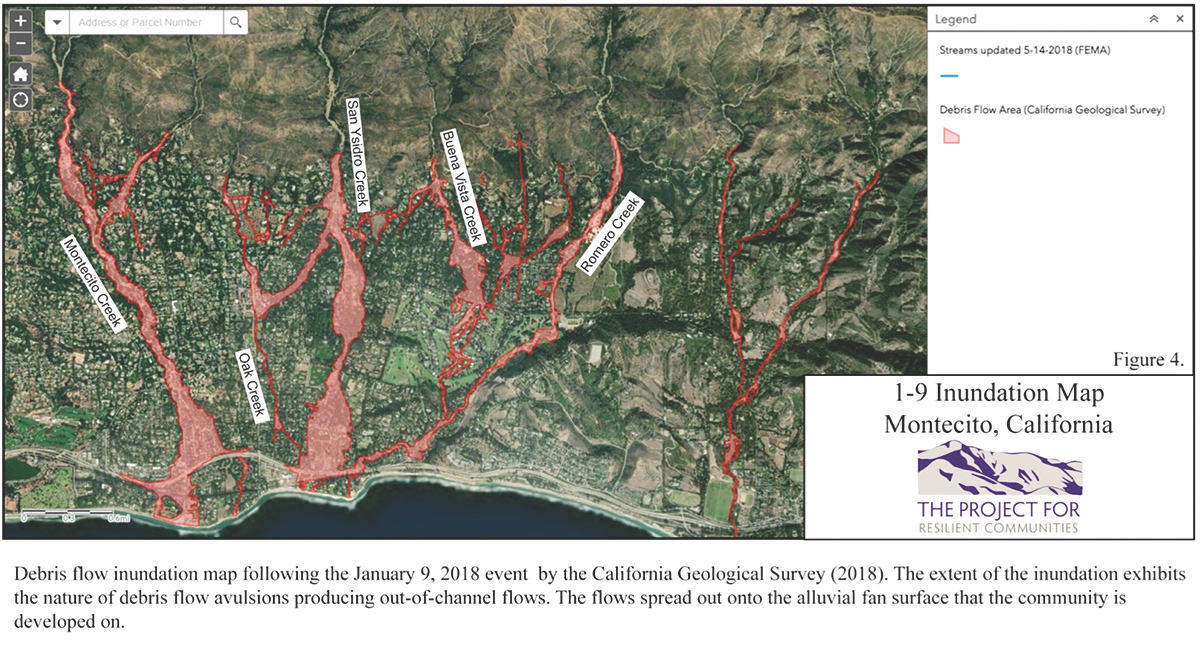

Chief Taylor points to a place on the map projected on the screen that shows Montecito Creek. He explains to me how these maps outline the watershed boundary for each creek’s watershed. What this means, according to Chief Taylor, is that the area of the watershed he points to on the map feeds Montecito Creek. These are landslide dams and previous debris flows, what’s called the alluvial fan. The Chief explains that the map reflects the actual flow paths of previous events in recorded history and the way that the creeks have changed as a result of those debris flows.

KT: We’re able to determine, from the LIDAR (laser imaging, detection, and ranging) studies in Montecito Creek, how much material will come off this mountain in a worst-case event.

GL: Can you talk a little about the ring nets and what if any impact they’re having? Particularly the upper net on San Ysidro that is filled with debris.

KT: I can tell you what I was told by Kane Engineering. They described the necessity of a series of nets that catch debris and slow velocity, so that when the debris gets to the base, there’s less material traveling at a slower velocity.

If you look at our creeks after this last event, there’s been substantial scouring. That means lowering of the drainage. The basins are full. It’s safe to say that the same way it’s scoured down here, it’s scoured higher on the mountain. As that high velocity water goes by, it’s picking up material. Small material this time, no Volkswagen-sized boulders (like five years ago). But it’s still picking up what they described as cobble and small material, that’s what’s sitting in the basins right now. Those nets slow the velocity of that material. Intuitively, I would think that means it would pick up less material until it got to the next one. I don’t remember the exact number, but I think 54 were required to actually be effective.

GL: In a massive event?

KT: Correct. In a 1/9 (2018) type event. Yeah.

GL: But is it safe to say that in a 1/9 type event, no matter how many nets you have on the mountain, the best solution is to get out of the way?

KT: Always. Here’s the challenge with debris flows. In the historical record for Montecito Creek, it shows all of the debris flows and debris-laden floods that have occurred.

GL: Can you describe the difference between debris flow and debris-laden flood?

KT: Debris flow is a wall of mud moving at a velocity that will move property from the pad that it’s built on to the Pacific Ocean, and everyone and everything that’s in it. It’s not a survivable event. A debris-laden flood is water with cobble and other dirt-like material mixed in traveling at very high velocity.

GL: Did that occur last Monday when we had to evacuate?

KT: Yes. The only way to fill a debris basin is to have a debris-laden flood. Here’s what occurred on Monday.

At this point, Chief Taylor shows me a map that is for internal use only, which he describes as a damage assessment dashboard. He explains to me that each of the colored marks on the map that he points to represents where a person entered a data point.

KT: And so as our folks are out there, they enter data points and they take pictures. So if we click on one of these, it’ll actually show a picture of what occurred in that exact area.

The Chief points to a picture on the projected map of a street in Montecito where a bridge was damaged from last Monday’s storm.

You can see here there is a bridge damaged; no follow-up needed. The guardrail’s down, but the bridge is still standing. So that’s a fairly low repair priority.

The reason why I’m showing you that example is, there were many good things that came out of this 1/9 storm. We know that there were 20 inches of rain in the previous 30 days, and we know that in some areas we received 12 inches of rain on the watershed. And we experienced debris-laden flooding, but we did not experience loss of life or significant property damage. That’s a result of the nets, the flood control system, and the basins.

GL: And the regrowth. Would you put that in there?

KT: As compared to 1/9/2018? Yes. But we’re still five years post-event, so we know that material’s going to move. We also know that if the basins hadn’t been there, or the San Ysidro net hadn’t been there, that material would’ve continued through the community. And eventually, because it’s traveling at such high velocity, it probably would’ve come out of the channel and gone somewhere else. History tells us that.

In 1964, and then in 1969, five years post-fire, there was a substantial debris flow, with the exact same total rainfall in 25 days, 6.6 inches (in one 24-hour period in 1969 compared to 12 inches in one 24-hour period on 1/9/2023) and it killed five people, and damaged 100 properties. This is what we suspected could happen. Remember, on the map, red means if you don’t leave, you could die.

Here’s what actually happened. What we know from looking at the damage reports, is that our map is accurate. In other words, no damage occurred in our community in an area that we did not expect it to occur.

GL: That’s great news.

KT: From an emergency manager standpoint, it’s the ultimate validation. So moving forward, we know with absolute certainty that if we think there’s going to be a debris flow, we don’t have to evacuate the whole community. We only have to evacuate those people.

GL: Can you explain though why you still might evacuate the entire community?

KT: Because we also know that if that occurs, the people that are between it, in those three areas, can’t get out. Because we know it takes us 21 days to clear it. Because we did it once. In 2018, it took us 21 days.

So in a case like this, when we’re issuing a protective action order, evacuation warning order, or an evacuation order, we fully staff the fire districts. Sheriff’s office fully staffs. Search and rescue fully staffs. And the City fully staffs. Then we have this thing called a rescue task force, which has 30 members; Santa Maria and Lompoc fire departments contribute to that as well. So we have a little over 250 people that are engaged before the storm has arrived. They’re managed by that incident management team. We have them at Earl Warren Showgrounds. They do briefings or whatever else in each community.

GL: You founded the incident management team, correct?

KT: Yes, the Fire Chiefs Association created the incident management team in 2015.

GL: And you were the incident commander of the 1/9 event (in 2018)?

KT: Yes. I was the incident commander of the 1/9 event. The incident management team was staffed on January 7th. Each community becomes a branch; that’s an organizational method that we utilize to ensure that we have clear lines of communication and authority. So we became the Montecito branch.

The Chief shows me another internal map that can’t be published.

KT: This map shows that if there is a problem, these are the properties that need to be searched first. You’ll notice that the red lines up with the red. The yellow is where there’s going to be nuisance flooding. That’s like a foot of mud, low velocity, just spread out. All of the properties are identified by a number that represents their site address. The map is broken up by grids. These are all national search grids in urban search and rescue. So if we had another 1/9 event, and let’s say a USAR (Urban Search and Rescue) unit from L.A. City was coming. On the way in, they might be assigned to a certain location on the grid and they would have this map on their phone.

GL: How many people did you rescue in this latest event?

KT: 50 people.

GL: Compared to how many in 2018?

KT: 900 people. Remember, a rescue is defined as somebody that can’t get themselves out of where they’re at.

In addition to those 250 firefighters, we provide all that equipment including helicopters and Army National Guard high water vehicles. All those things are in place at Earl Warren before the storm comes. When the storm hits, we have people that are responsible for certain areas of the districts.

We have four divisions: We have Cold Spring. Then we have one called North, we have one called South, and we have one called Olive. We divide the district geographically, again for span of control, so there’s somebody by name that’s in charge of each area. We call this our senior leadership; they are responsible for everything that occurs within that geographical boundary.

GL: Who was the incident commander this time?

KT: David Neels (Division Chief, Operations) and Anthony Stornetta (Santa Barbara County Deputy Fire Chief, Operations). That incident management team is hired formally on paper by those jurisdictions that were on the storm impact consideration decision team. And there’s always a Sheriff’s representative.

The incident management team is responsible for all 3,789 square miles of Santa Barbara County. They had issues everywhere this time. Whereas on 1/9/2018 only Montecito had issues. This time, Santa Barbara County had issues everywhere. All the way down to Carpinteria.

GL: I wanted to have this conversation because I want the community to understand all the thinking that goes into making these decisions. And that you also are mindful of the hassle and stress that’s caused by evacuation. That you don’t want to put people through that unnecessarily.

KT: Absolutely. Those six principles that you saw, that’s why each one of those decisions are so intentional. The daily meeting at two o’clock is intentional. That’s when we have the very best forecast from the highest resolution weather model available. There’s an incredible amount of work that goes in before that meeting to evaluate how much rain we’ve had, what the saturation level is, status of the debris basins, status of the creek channels. We collect that data, flood control collects that data. We exchange the data so that everybody’s on the same page.

GL: And then you study the whole thing again in retrospect, correct?

KT: Yes. After the storm, we send out teams from our organization to evaluate the watershed, debris basins, debris nets, and creek channels. They have a two-page inspection report that they complete by 10 am the next day. We then compare that data with the flood control department report. We also evaluate how much rain has fallen in the last 24 hours, 48 hours, seven days, and 30 days. We average the five automated rain gauges above the community. We also do aerial recon either by helicopter or drone to determine if any major movement has occurred high up on the mountain.

We have been doing this since the 1/9/2018 Debris Flow and have a pretty accurate record of how the watershed reacts to both volume and intensity of rainfall. All of this data is considered in advance of the 2 pm Storm Impact Consideration Team meeting.

Finally, if a protective action is ordered (shelter in place, evacuation warning, evacuation order) we determine if it was necessary after the event. This analysis includes everything above plus the actual storm damage reports.

GL: The 50 people who were rescued, do you know why they did not get out?

KT: We don’t ask. The sheriff is very clear that he respects the Fourth Amendment rights of individuals and that he will not forcefully evacuate somebody from their home.

GL: So, if everyone had left when the order was given, there would have been no rescues.

KT: Correct. Here’s how that works. We asked community members, after 1/9/2018, why did you evacuate? Why didn’t you evacuate? And there’s a lot of scientific data on this from Hurricane Katrina and other disasters. The evacuation peer-reviewed literature is rich. When an evacuation order is issued, if a community member doesn’t understand or doesn’t believe, they validate the information with someone that they trust. The gap in time between when the evacuation order is issued and when they leave, the scientific term for that is milling. Emergency managers try to develop strategies to reduce the amount of milling time. The very best strategy is credibility. If a trusted and credible member of the community says evacuate, there will be no milling. They’ll trust the order.

That’s super easy in a fire, because you can get an evacuation order and look and go, yep, there’s smoke. Here it comes. It’s not so easy in flooding.

GL: So it’s not just that your home might get swept away, it’s get out because you might get stuck in your home for 21 days.

KT: Yes. There are two reasons why we didn’t only evacuate the red areas, we evacuated the entire community last Monday. First, the senior leadership is monitoring the rainfall. All of our units have computers in them, and they’re actually monitoring in real time what’s occurring. And they’re seeing rainfall amounts that are both high intensity, short duration, and saturation. They had seen eight inches of rain since 3 am. Remember, the evacuation order went out around noon. And so they started to see things; the watershed was reacting in ways they had never seen before. And remember, we use the term senior leadership intentionally. They’re very experienced in emergency decision-making. And they said, “Chief, we recommend evacuating the entire fire districts.”

GL: So the watershed reacting in ways that you hadn’t seen before, what does that mean?

KT: It means that they were seeing runoff in areas there’s not normally runoff. They were seeing material in areas where they expected clear water. So they’re going to err on the side of safety because that’s our number one evacuation principle.

When you’re the fire chief, if you have the right people in place and you trust them, you would be a fool… Matter of fact, you would be negligent if you didn’t follow their advice. That’s why you have them there. They’re chosen intentionally. And so of course we evacuated the entire community. But, as I showed you on this map, we really learned a lot. Because we know that if we get 20 inches in 30 days, and then 12 inches in 24 hours, this is how the watershed’s going to respond. That’s where we’re going to have our damage from a debris-laden flood… This event is recorded. We keep a matrix. And all of the events are recorded to help inform our decision-making.

GL: In light of the recent passage of state legislation SB9 and SB10, which allows for more housing and greater population density in areas like Montecito, do you believe this will have an impact on your ability to evacuate our community in times of disaster?

KT: Yes. We have an evacuation study done by a professional traffic engineering firm. And it says that our existing infrastructure, specifically roadways, do not support a very fast evacuation. That’s not such a big deal in this type of an event. But in a wind-driven wildfire, it is a very big deal. If the Tea Fire occurs, we know that we’re going to be challenged to get everybody out from in front of that.

GL: Today?

KT: Yes, as is today. So operationally, we’re reexamining our entire evacuation plan, given the current population, to make it more refined and precise. What we’re shooting for, and Montecito Fire shoots for this in everything, is exceptional, always. Good is not good enough. We always have the hard conversations. Everything that we do, when it’s done, we evaluate whether it was the right thing to do. Including this full community evacuation. We asked, why did we do it? What was the intended outcome? What was the actual outcome? Were there unintended consequences that we didn’t foresee? And then that’s all recorded, so that next time we can move the organization from good to exceptional. And we want to be exceptional, because we serve an exceptional community.

GL: Is there anything else you’d like the community to know?

KT: Yes. If I could ask you to have any slant, while I get the credit for a lot of this, the credit should go to every member of every fire department on the south coast of Santa Barbara. We have this incredibly close relationship that allows us to work together seamlessly, and what comes out the other end of that is all our communities get this really great service.

GL: Thank you for everything you all do.