Plaza del Mar and the Bandshell

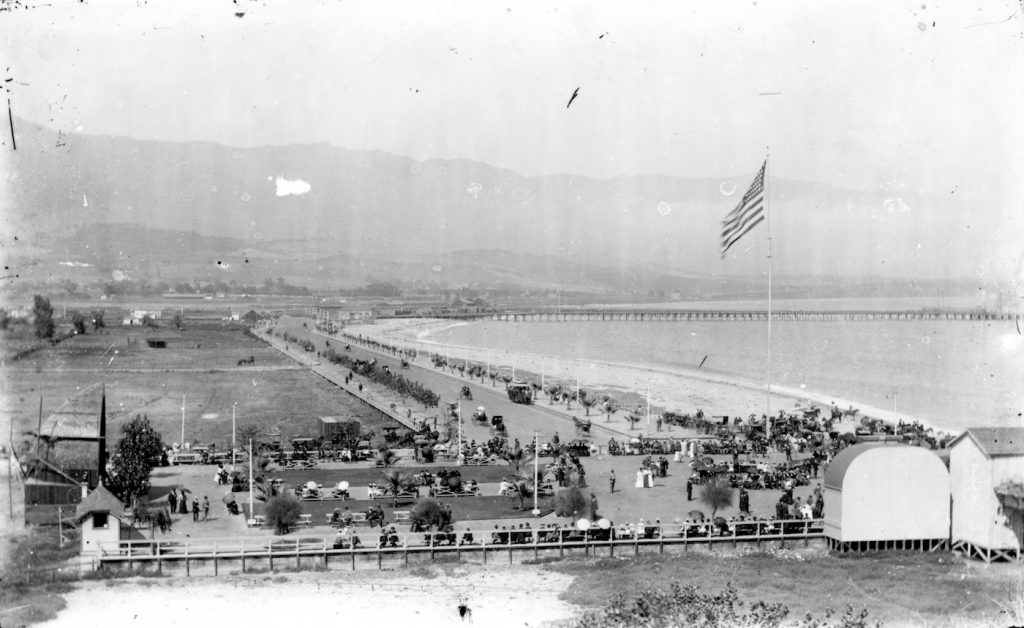

In 1886, the Santa Barbara waterfront was connected to three, often odiferous, esteros and littered with dilapidated shacks and the detritus of the hide and tallow industry. Despite the fact that there were several crude wooden bathhouses, the area was generally a “wild waste of sand, tin cans, and dead animals,” according to historian C.W. Gidney.

In 1890, local promoters began advocating improvements for the beach on the west side of State Street. They wanted a public plaza, a road around Castle Rock, and a grand boulevard. The expenditure would soon pay for itself, they claimed, due to the fame it would bring to the city. Committees were formed.

In 1891, Henry Chapman Ford, a committee member and reputedly Santa Barbara’s first resident artist, created a watercolor rendering of tentative plans for the area of West Beach. After plans were adopted in October, civic promoter Thomas B. Dibblee, who owned the estate on the hill above the beach, donated his lands at the foot of the bluff for the plaza.

When the plaza was completed in April of 1893, there was an immediate call for summer Sunday concerts. Also immediately, City Council passed Ordinance #259, making it illegal to sell liquor or establish saloons within 1,600 feet of Plaza del Mar. Penalties began with a fine of $100 and progressed to jail time for repeated offences.

Plaza del Mar had been laid out in front of Fred Forbush’s wooden bathhouse, and in exchange for the looking after the plaza, he was granted permission to use the water there. Neat white fences surrounded the plaza, which was laid out with sections of lawn lined with wooden benches. A bandshell anchored the north end, and the streetcar line ran along the concrete boardwalk. The plaza was an immediate hit with the populace.

Mirth and Music capped off that first season of the band concerts, given by Professor J.E. Green’s band of local musicians. An enthusiastic reporter described people flocking to the wharf, the beach, and the boulevard armed with picnics and good cheer. The mule-drawn trams were overloaded with passengers and rushed to deliver their cargo. By the time the concert started, the Plaza was choked with well-dressed people. Professor Green’s young musicians received roaring applause and multiple demands for encores.

After the musical program ended with “Auld Lang Syne,” a special surprise awaited the audience. A monster balloon rushed skyward carrying a daring young man with a parachute. As the balloon rose higher and floated seaward, the moment came when the aeronaut released his hold and dropped down like a shot until he engaged a double parachute. Amidst the gasps of the onlookers, he floated gently down to the sea where he was picked up by a waiting boat. Quite the end to a successful first summer season at Plaza del Mar.

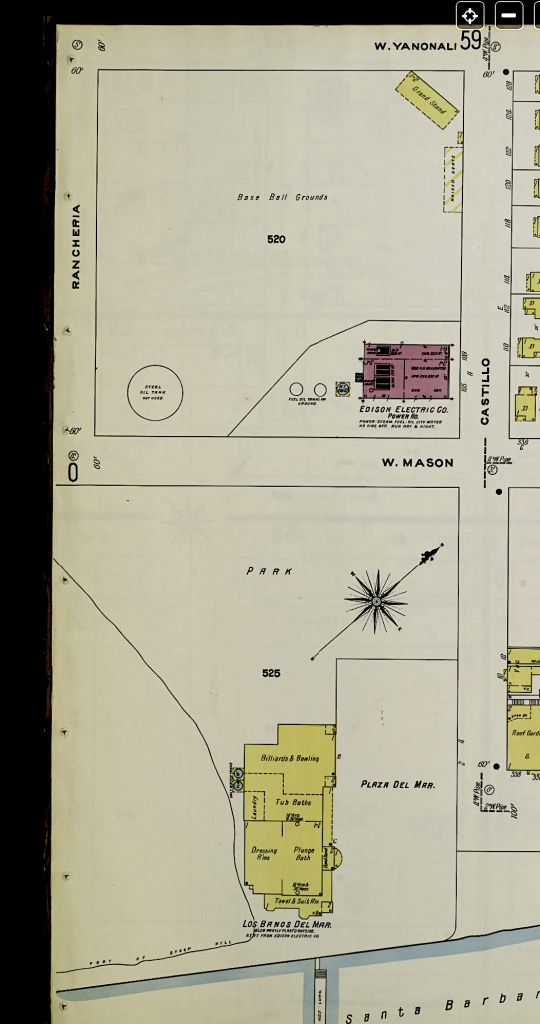

Los Baños del Mar

In 1899, the lands bordered by the extension of Mason Street, Castillo Street, the Dibblee bluff, and Plaza del Mar were added to the city park system. As a consequence, there was a renewed push for a better bathhouse. A campaign of letters to the editor peppered the newspapers. When the Chamber of Commerce took up the project, they negotiated with United Electric Gas and Power Company to build a powerhouse for the city and a bathhouse on property recently acquired west of Plaza del Mar, thanks to funds donated by a group of civic-minded citizens.

Completed in 1902, the Mission Style bathhouse was touted as the “pride of Santa Barbara.” It featured two plunges, 150 rooms with baths, including a number for hot salt water baths. The water was heated and changed several times a day. There was also a bowling alley with four lanes, a pleasure pier, and a second story bandshell. At night it was brilliant with electric lights shining from arches, domes, and windows.

Band concerts became even more popular. When the Italian heartthrob Caesar LaMonaca and his band were brought to town by a group headed by Mary Miles Herter (the widow of Gilded Age furniture maker Christian Herter and mother of artist Albert Herter and the future Secretary of State Christian Herter), the musical community seemed to have reached its zenith.

In March of 1913, the bathhouse burned to the ground in a fire of unknown origin, but suspected, ironically, to have been caused by faulty or worn electric wiring. Now called Southern California Edison, the electric company planned to rebuild. In the meantime with the death of Mary Miles Herter in 1913, LaMonaca’s band played a final farewell concert in December.

World War I burst on the scene in 1914, nevertheless, a new bathhouse was constructed. Designed by H. Alban Reeves of Los Angeles and Russell Ray of Santa Barbara, it opened in April 1915. It lacked a bandshell, however, so a freestanding one was placed nearby. Attempts were made and subscribers recruited but no municipal band was found for the summer season. An amateur Italian band formed in town, however, and offered free Sunday concerts late in the season.

There was, however, a problem with the bandstand at the plaza, and soon concert patrons were demanding a new bandshell that would make the music audible. One letter writer to the Morning Press said the bandshell was “a receptacle for the full strength of the ocean breezes that blow straight into it and raise havoc with the sweet strains of music.” Another wrote that more people would attend the concerts if the bandstand weren’t “as poor an excuse for a thing of its kind as could be provided and is an exasperation for both players and listeners.”

A Proper Bandshell

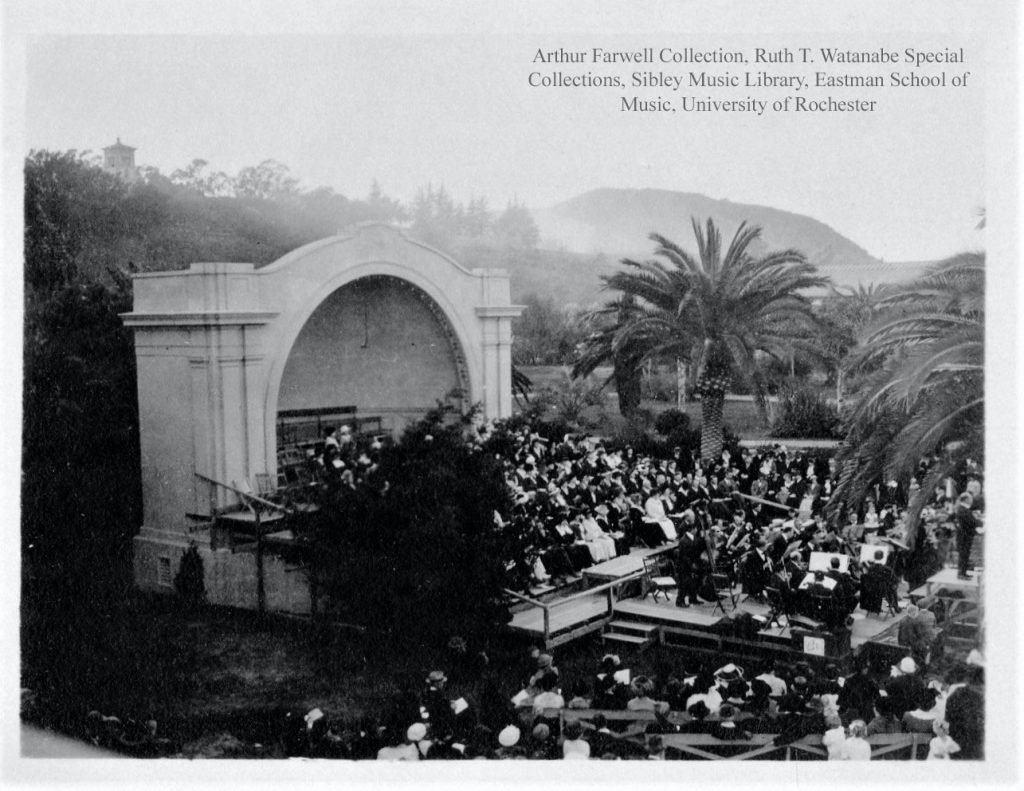

After World War I, a reinvigorated Chamber of Commerce stepped to the forefront and formed a municipal band committee. They raised subscription monies to hire Rocco Plantamura to assemble a 22-piece band to furnish music for a concert program at Plaza del Mar and elsewhere. Plantamura was no stranger to Santa Barbara; he had been part of LaMonaca’s band for several years past. And best of all, his first concert was to be played on Sunday, May 4 in a new bandshell designed by architect Winsor Soule.

Though the shell wasn’t quite finished, the concert was a rousing success. Nearly 5,000 people crowded into the park and came away pleased and impressed with the ease and grace of the new conductor who brought out the beauty of each selection. Encore after encore ensued, and Plantamura varied his classical score with more popular tunes and even threw in a little jazz.

The area around the bandshell continued to be improved under the supervision of Superintendent Ralph Tallant Stevens of the park commission. Turf was replaced by a graveled semi-circle to accommodate the benches, and trees obstructing the view of the stage were replanted behind it.

Having provided for the band, the Chamber of Commerce asked that the city buy the bandshell because they did not have money to complete payment for its construction. The estimated cost of $2,000 had grown to nearly $4,000. Many meetings passed before the contractors received the remainder of their fees.

In 1919, conductor, ethnomusicologist, and co-founder of the national Community Chorus movement Arthur Farwell was enticed to come to Santa Barbara to establish a community chorus. Practicing for several months at the Recreation Center, on November 13, the Chorus gave its first concert at the new bandshell of Plaza del Mar to an audience of 2,000 people. Everyone was urged to take part. “Those who had come merely to listen,” reported the newspaper, “found themselves drawn-in irresistibly to the current of the music.”

“It was in every sense a Pan-American gathering,” continued the reporter wryly, “the voices of the chorus rising in lusty and good-humored competition with the enthusiastic rooters for the baseball game then in progress down the block… It is apparent that the chorus is going to become a powerful rival of the Great American Game.”

On December 28, Farwell led the chorus in a program that was accompanied by 30 musicians from Los Angeles. Comprised of Spanish songs, Christmas carols, and the works of Handel, Haydn, Wagner, and Gounod, the concert played to a packed park as seating stretched all the way to Castillo Street.

The band concerts continued, but in July 1920 something new was afoot. A fledgling Community Arts Association brought Samuel Hume and Irving Pichel of the theatre department at Berkeley back to Santa Barbara after their earlier staging of La Primavera in April. Hume and Pichel organized the populace to take roles in The Quest, a masque written by Berkeley graduate Sidney Coe Howard and first performed at the Cranbrook estate in Michigan by Hume and Pichel.

Hoping to lay the foundations for an outdoor community theater in the parkland of Plaza del Mar, the organization had the trees shielding the slough and hillside from the park cut down. The slough was drained and filled with seawater to form a lagoon. Kem Weber, later a famous architect and noted designer of modern-style furniture, built the stage in a curve of the hillside. The road winding down the hillside from the Leadbetter (former Dibblee) estate was utilized to bring parades of costumed actors to the stage while other actors approached by boats in the lagoon.

The Quest ran for three nights starting July 15, 1920. Though lauded by those who saw it, it was not largely attended and the idea for an outdoor community theater was abandoned, though the Community Arts Association became established as an organizing and driving force for the arts in Santa Barbara. (See the upcoming Noticias of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum.)

Raising sufficient monies for band concerts were a yearly concern, but in 1921, a writer to the Morning Press was able to say, “Cheers for the city council! Three cheers — and many more — and tigers and hip-hoorays! Councilmen announce that beginning soon, beach Sunday concerts will be resumed!”

A small fund was able to pay for one concert a week, played on alternating Sundays by the American Legion and Father Villa’s Boys’ bands.

“For these many months,” lamented the writer, “Sunday at the beach has been everything that blue-spectacled, Puritanical joy-killers could wish. With nothing but the soughing of the sad sea waves to break the funereal stillness, those who had gone to the beach because it was the only place to go have sat like mourners, sleepily nodding, listlessly waiting and wishing the close of the day and time to go home to supper…. A note of musical cheer will make the beach another place. So cheers for the councilmen!”

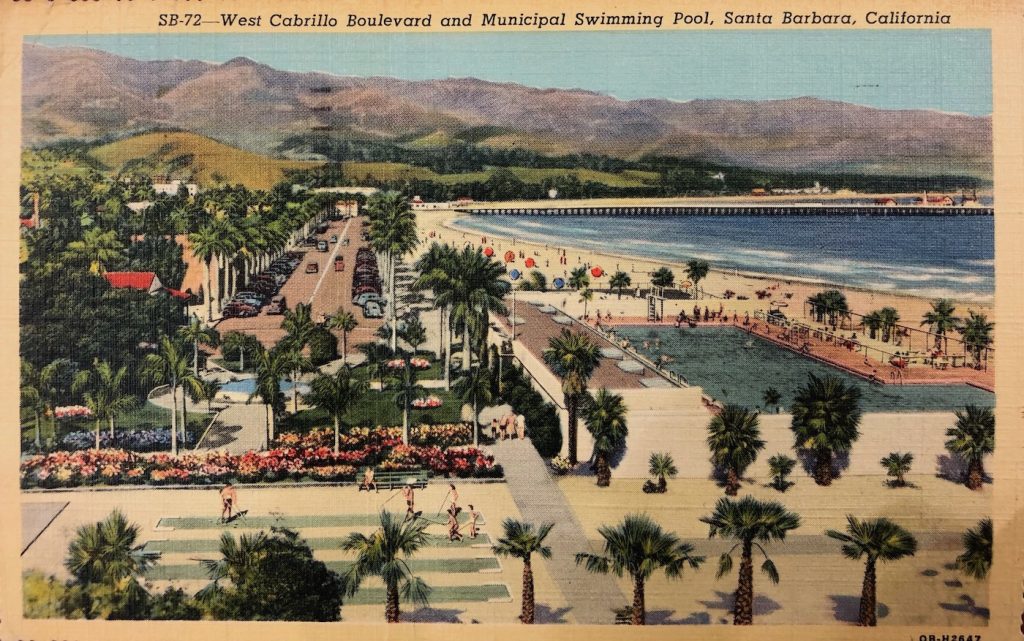

The second Los Baños del Mar was destroyed by the 1925 earthquake and not rebuilt. Instead, a simple plunge was constructed on the beachside of Cabrillo Boulevard, which was later extended up the bluff as Shoreline Drive. The 103-year-old historic bandshell has lain dark for many years now and awaits restoration and new performers to provide us with that note of musical cheer.

(Sources: Contemporary news articles, University of Rochester, “The Quest” by Mary Morris.)

Hattie has been writing a local history column for the Montecito Journal for more than a decade. She has written two Noticias and coedited My Santa Barbara Scrap Book, the memoir of local artist Elizabeth Eaton Burton, for the Santa Barbara Historical Museum. Her book, The Way It Was ~ Santa Barbara Comes of Age, is a collection of a few of her nearly 400 articles written for the Journal. She is the researcher and author of Celebrating CAMA’s Centennial, a chronicle of the Community Arts Music Association’s 100-year history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.