A Life in Focus

From photojournalist in Tennessee to two tours as Second Lady to a new start in Montecito, Tipper Gore has had a remarkable journey

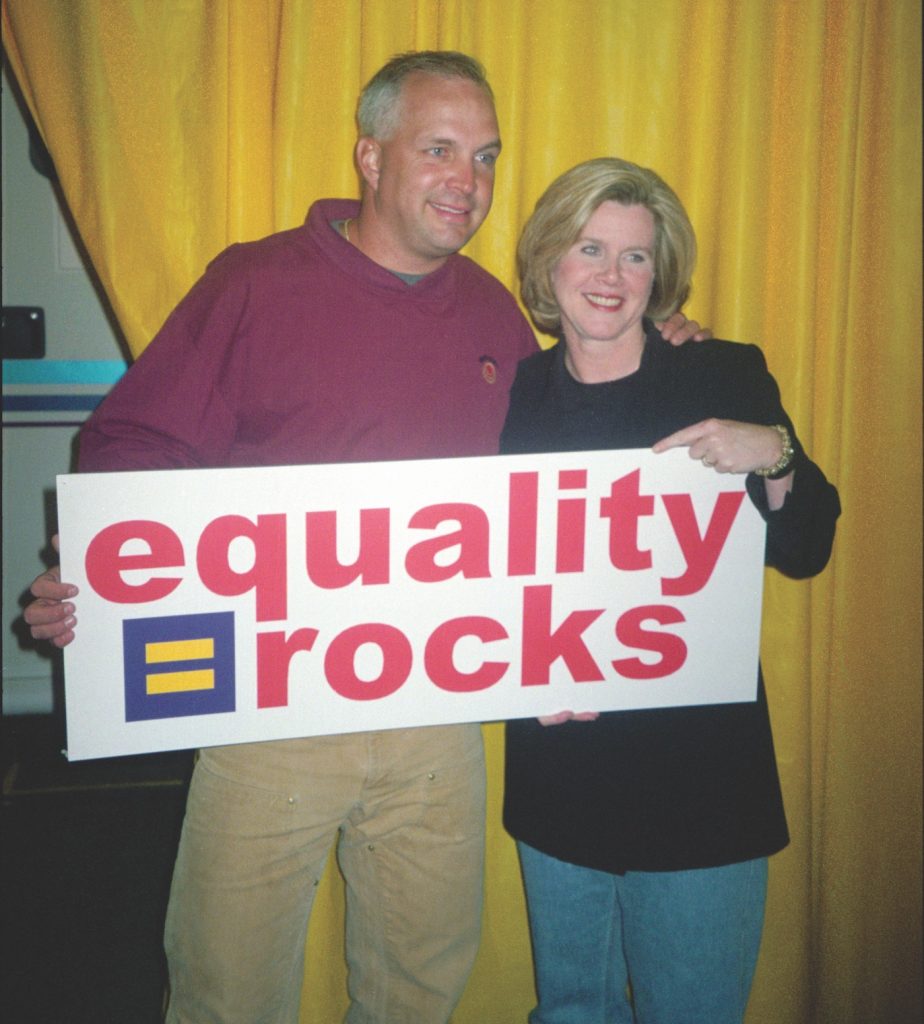

To spend time with Tipper Gore – even by phone, as I did, thanks to COVID-19 safety restrictions – is to marvel at the vivid tapestry of her life. As the nation’s Second Lady from 1993 until 2001, she advocated for numerous social and mental health causes, serving as a mental health policy advisor to then-president Bill Clinton and becoming a passionate supporter for the homeless. A longtime champion of LGBTQIA+ equality, she was one of the highest-ranking representatives in the Clinton administration to participate in the first AIDS Walk in Washington, D.C. As cofounder of the Parents Music Resource Center, she increased consumer awareness of violence and misogyny in popular culture, and in so doing, became a flashpoint for the culture wars around speech and artistic expression.

Yet her deepest passion – apart from her family – may be photography. Tipper Gore has been reaching out to others through her lens for five decades. Her career as a photographer preceded her family’s involvement in politics and lies at the core of her advocacy and art. While she’s focused her lens on political events, travel destinations, personalities, and humanitarian crises, these days she takes her inspiration primarily from the natural world.

Tipper divides her time between her home in Montecito, which she has owned since 2010, and her farm in Virginia, where she is spending the year of COVID-19. The Montecito Journal connected with Tipper Gore to discuss photography, public service, her enduring spiritual practice, and her unexpected friendship with Frank Zappa.

Q: Tell us your photography origin story.

A: My mom, who raised me in Virginia, is the one who introduced me to photography. She had a broad-ranging interest in the arts and often took me to the museums in Washington, D.C., such as the Smithsonian, The Phillips Collection, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, as well as to concerts, plays, and the ballet. Growing up in Washington, D.C., there were lots of opportunities to see art; pieces and exhibits would come on loan from around the world. I remember standing in line with my mother to see the Mona Lisa when it was exhibited for the first time in America at the National Gallery of Art in 1963.

Music has also been another important part of my life, and that goes back to my mother, too. She really appreciated classical music and would take me to concerts at the Kennedy Center. I enjoyed those experiences, but once rock and roll hit, for me that was it! The Beatles, The Ventures, Smokey Robinson, Buffalo Springfield, Dionne Warwick, Fleetwood Mac…. I listened to them all. My mother arranged for me to have guitar lessons and bought me my first drum kit when I was 12. She put it in the basement, bless her heart! Of course, she was a single working mom so she wasn’t in the house during the day while I was practicing. I would come home after school and play music with my friends, and she’d get home a few hours later. In high school, my friends and I formed a band called the Wildcats and we had a lot of fun.

You attended St. Agnes, a private Episcopal school in Alexandria, Virginia, and met your future husband at his high school senior prom in 1965.

That’s right. As it turns out, we both pursued our education in Boston. He attended Harvard University and I got my degree in psychology from Boston University. Al and I married in 1970, and I earned a master’s degree in psychology in 1973 from George Peabody College for Teachers, which is now affiliated with Vanderbilt University. My goal at that time was to be a counselor, working with children and families.

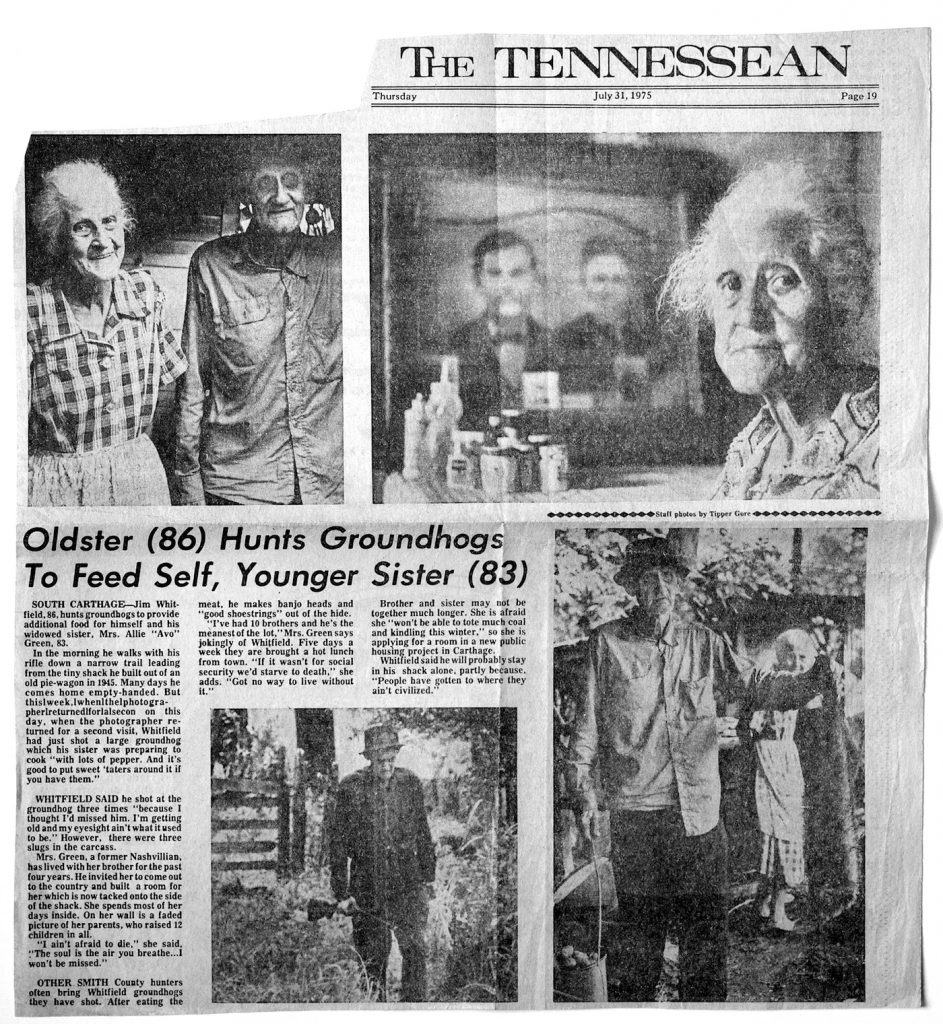

But my life took a different turn. That same year – after I had my first child, Karenna – Al and my dear friend, photographer Nancy Rhoda, encouraged me to take a photography class with Jack Corn, the photo editor at the Nashville-based Tennessean, whose work I had long admired. We were living in Virginia, in the house my grandparents built in 1936. We spent the summers at Al’s family farm in Carthage, Tennessee, and that’s where we were based when I started taking Jack’s class. I commuted 100 miles round trip to get to the Tennessean. But I loved what I was learning.

Jack was an excellent teacher and instilled in me a devotion to using photography as a means of communication. By capturing an unusual image and telling a story, I could challenge or shift viewers’ perceptions. Jack told me to take my camera with me at all times and just shoot, shoot, shoot. He said, “Show me anything you have shot, and if it is good enough, we will see about running it in the paper.” That was back in the day when newspapers were featuring photo essays prominently. I still remember how excited I felt when I published my first story – with four photographs – one of which was picked up by The Associated Press wire service.

Jack ended up offering me a part-time job, and pretty soon I was working on stories, taking photographs, and writing text and captions. I also developed the staff photographers’ film and learned the printing process, and that’s what I was doing when Al had the opportunity to run for Congress in 1976.

I remember being a bit conflicted at the time, because I loved my job and didn’t want to give it up. So I spoke with Jack about it. “Al is going to win, and your life is going to change,” he told me. “But if for whatever reason he doesn’t go to Congress, your job here will be waiting for you.” In the meantime, he advised, “Keep taking pictures. When you see an image that you need to capture, or a face in the crowd, or an idea you want to convey, you’ll know. But don’t get caught seeing it and not have your camera with you. Always carry equipment and you’ll be prepared.” He gave me the idea that I could continue with photography during my political life. So during that first congressional campaign and beyond, I always kept my camera with me; it was a small Canon Z135 film camera that I could whip out quickly. And other people just got used to seeing it, too.

I decided to build a darkroom in the basement of our Virginia home. Jack told me how to do it, step by step. Some friends from The Washington Post came over to help me put it together. I loved working in the darkroom. I would print my own photos of my kids, landscapes, black-and-white images for my two books about the homeless – one in 1988 and another in 1999 – and pictures that I took during campaigns.

Can you name some of the photographers who have influenced you the most?

Jack Corn, Nancy Rhoda, and my fellow photographers were of course very powerful influencers. For a time, I was part of a group of very talented women photographers in Washington, D.C., and we’d have dinner together once a month. The group included the photographer Jodi Cobb, Newsweek photographer Susan McElhinney, and The Washington Post photojournalist Susan Biddle. I learned so much from those women.

Some of the other artists whose work speaks to me include W. Eugene Smith for his masterful photo essays; Edward Weston for his elegant natural landscapes; Mary Ellen Mark, who conveyed the idea of using photography to expose an issue; Robert Frank for his portrayals of small-town America; and Dorothea Lange for her ability to put a face on suffering and convey the reality of that time in a way that spoke to people. That’s what you want. If you make a photograph that speaks to a lot of people, you’ve really achieved something.

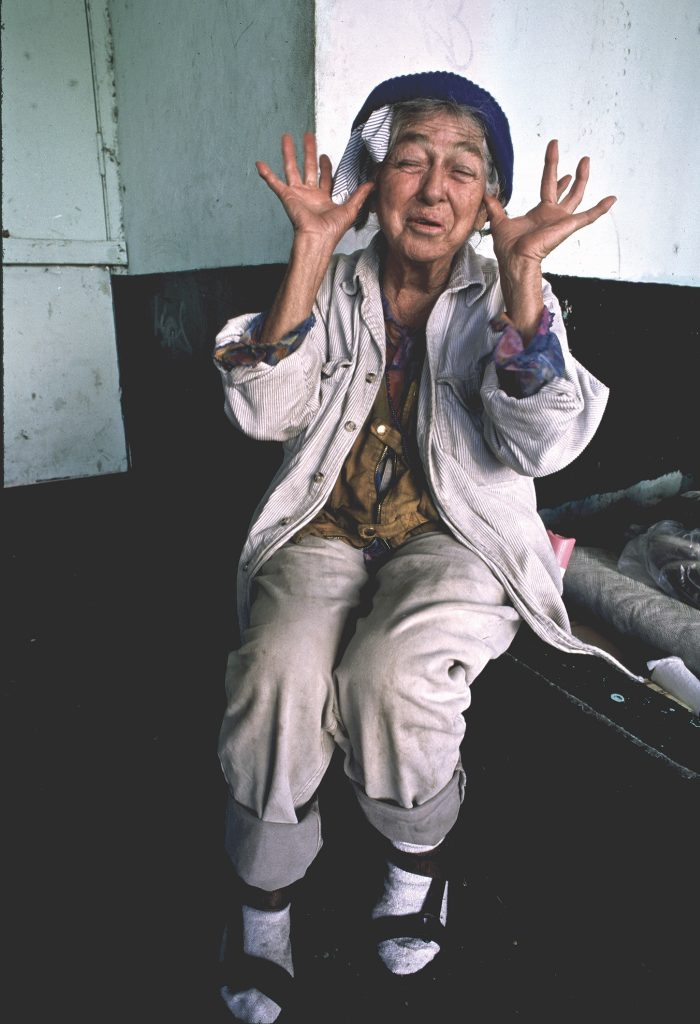

My first child, Karenna, was born in 1973, followed by Kristin in 1977, and Sarah in 1979. By the time our youngest, Albert, was born in 1982, Al’s political career was well underway. But even as our family’s political life intensified, I continued to educate myself by attending workshops and seminars. One weekend, sometime between 1973 and 1975, I drove to Atlanta to attend a presentation by W. Eugene Smith. Years later, in the early 1980s, I went to the The Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts for a weekend photo workshop taught by the award-winning Washington Post photographer Frank Johnston. This was after Al’s successful campaign for Congress and our move to Virginia. I was becoming involved with issues such as homelessness, mental health, violence in the media aimed at children, and elder care. And while I advocated for those causes through various means, I knew I could help illuminate these challenges and shift public opinion through images.

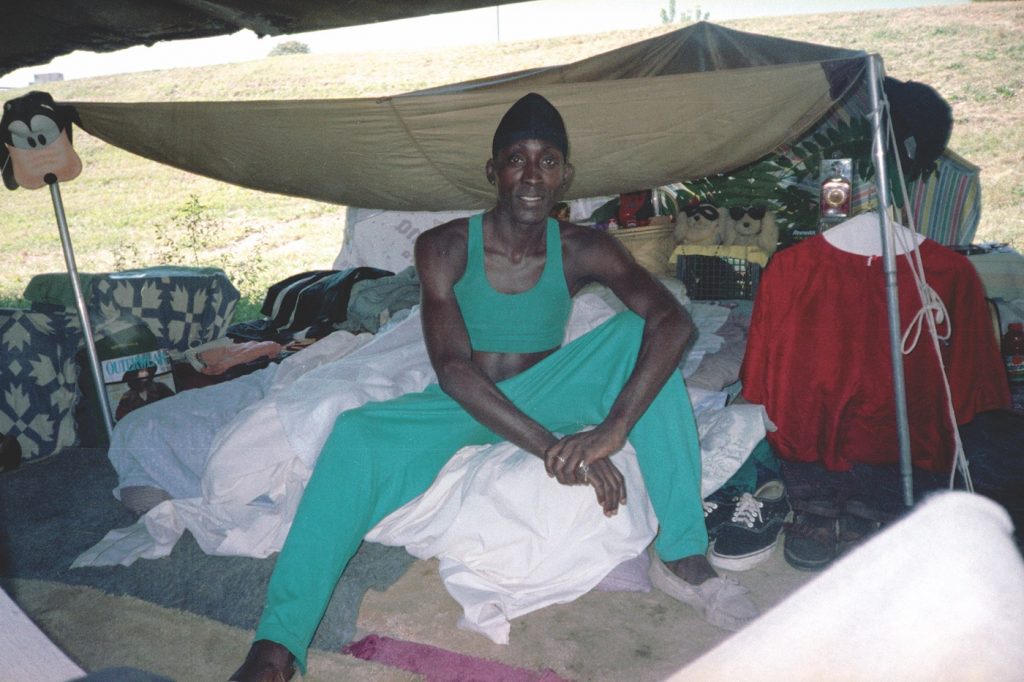

That is what I was thinking when I worked on my books: Homeless in America and The Way Home: Ending Homelessness in America. I wanted to take images not of homeless people, but of people who also happen to be homeless. They too are part of America.

Tell us a little about those early days in politics, campaigning with Bill and Hillary Clinton.

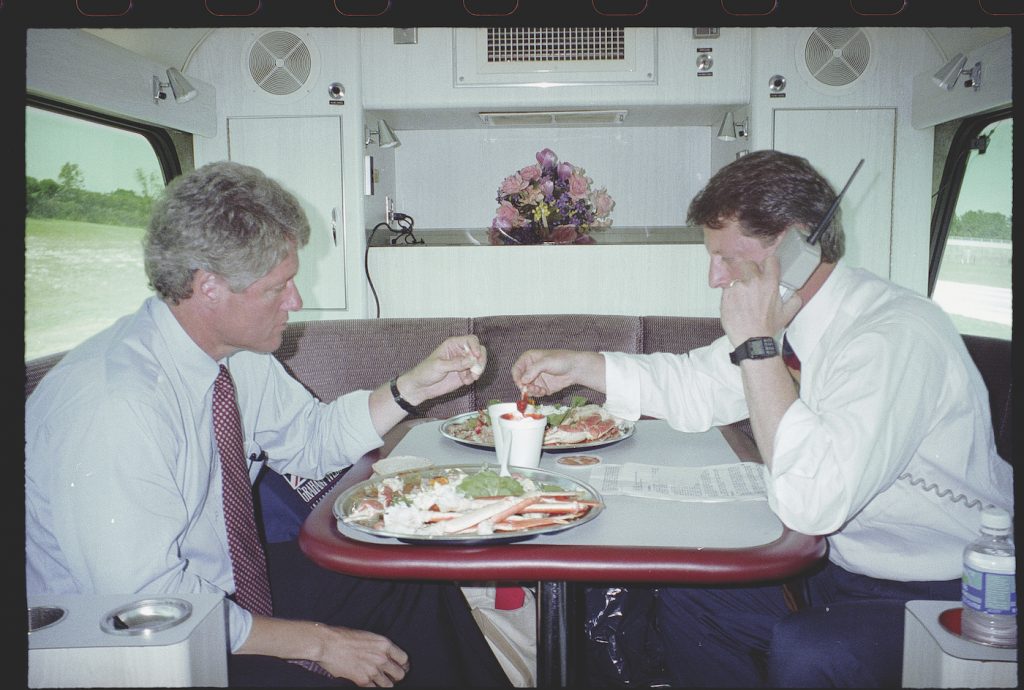

When we were crisscrossing the country on the campaign bus, we’d come to a stop and would switch it up. Sometimes we divided up our talking points. One day I might go out there and make a few remarks and introduce Hillary. And the next day, she’d do the same for me, or we’d both introduce our husbands. We gave thousands of speeches to huge groups over the years – from campaign groups to labor organizations to churches to civic groups of all kinds. I was not shy. I often spoke with no prepared notes. I felt truly honored to be able to meet and engage with Americans from around the country and to learn more about their concerns.

How did photography fit with your life in politics?

When we were in politics, photography gave me another raison d’être. With a camera, I became the narrator of the story, too. During the two presidential campaigns with Bill and Hillary Clinton, I took tons of photographs, which I’ve archived in my personal collection.

Jack Corn was the one who suggested I document the experience of campaigning through photography. And it really changed how I experienced those times. At the start of an event, I would go in front of a crowd and say a few things, often with Hillary or Al. But then I’d step back and, if the time was right, I’d pull out my camera. That image of the then-candidate Clinton speaking, which I’m shooting from behind – I love that image. I’m behind the lens, not in front of it. Images that evoke some of the elements of campaigning include the one of the little boy with the flag draped over his head, or the girl who’s throwing confetti. These images show how I used my camera during the campaigns.

As Second Lady, you had numerous responsibilities. Even so, you produced a body of photographic work that made powerful statements about politics, race, and national identity. Was it difficult at that time to balance your artistic self with service to the nation?

As Second Lady, I vowed to myself to stay as grounded as possible. And because I was able to spend time behind the camera, I think, I felt protected. I knew that that was a really important thing for me to do, at first for four years then eight.

At the same time, I used my camera to communicate, to educate, and to show a different perspective on political life and public service. At the Tennessean, I learned a basic tenet of photojournalism: capture the moment, and don’t alter the reality. I used my camera to try to show what it was like behind the scenes at the highest level of public life.

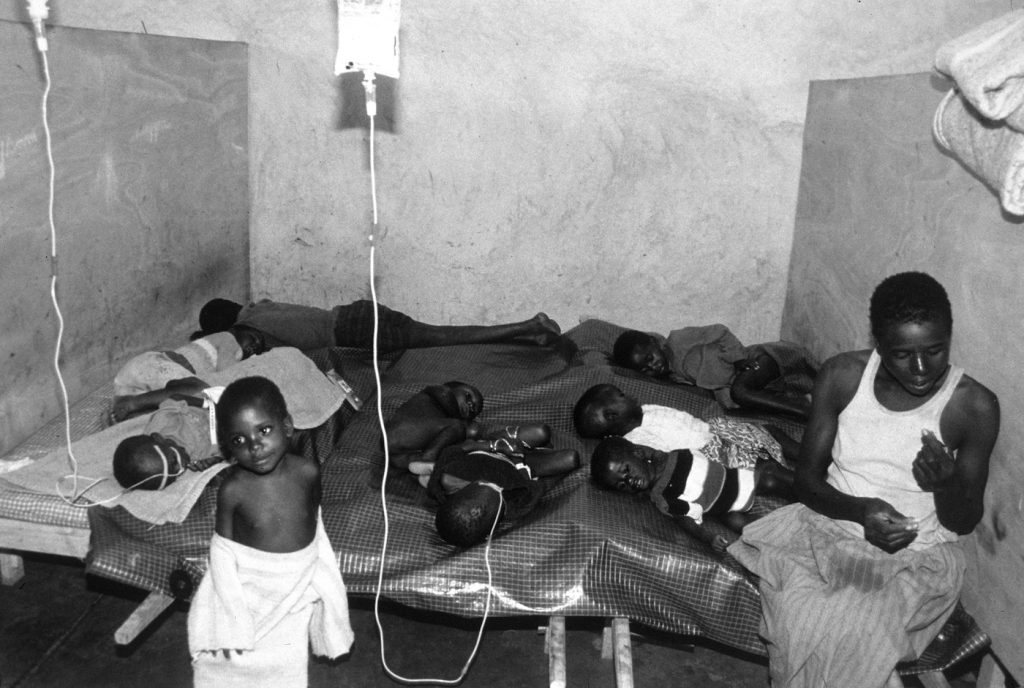

I also used my camera to put a human face on homelessness. I used it judiciously in Rwanda to show the effects of the horrible ethnic war and its devastating consequences on people and children. In these contexts, I understood the power of an image to educate and inform.

At a time when most of the world was averting its eyes from the horror of the Rwandan Civil War, you decided to travel to Rwandan refugee camps. What prompted that decision?

When I learned about the atrocities in Rwanda, I wondered why we weren’t doing more about this terrible humanitarian crisis. I felt as though I had to do something and draw attention to those who were suffering. The secretary of defense tried to dissuade me by advising that it was too dangerous. But I felt like it was a moral imperative. I got a ride with a friend who was taking medical supplies for the International Rescue Committee and I brought along my communications director, Sally Aman.

This was August 1994. Refugee camps were filled with the injured, the starving, the sick and dying. I went in with Rick Hodes, a doctor with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. I remember holding up an IV bag that he used to rehydrate a patient. I recall watching a single French nun struggle to care for a roomful of orphans. There was just so much need and very few resources for those providing medical care and other forms of desperately needed aid.

I knew that the images I was capturing on that visit could have an effect. Increasing the visibility of the situation was a way of making the case for various types of aid and support. I was able to share those photos on TV, and they had consequences on public opinion and policy. I remember appearing on the Katie Couric show to talk about my trip, and a $10,000 check arrived at the International Rescue Committee before the show had even finished. After that, the administration got more involved in the reconciliation movement.

I also took photographs in order to show how programs of caring can work and how aid translates into action. I went to New Orleans just after Hurricane Katrina to document the relief efforts. In 2005, the Tennessean ran that series of photographs.

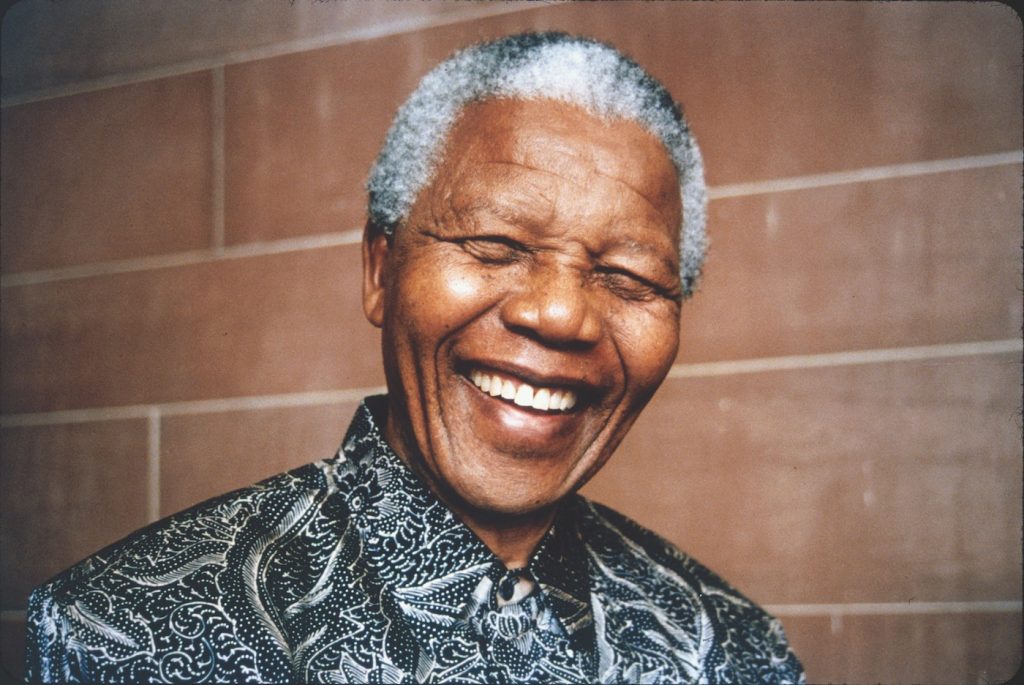

Your photo of Nelson Mandela stands out as a terrific study in character. Can you tell us about that experience?

Al and I visited him at his home in South Africa, which he shared with his wife, Graça Machel. He was just extremely nice, thoughtful, and sweet. After a lovely visit, I asked him, “Would you mind if I took a picture of you?” And he said, “Sure!” It was always an amazing experience to be with him.

Another time, we visited his former jail on Robben Island, where he had been imprisoned for 18 of the 27 years he served behind bars. That was an extremely moving experience. At his inauguration in 1994, which we attended, there was a party after the ceremony in a big tent, and Mandela told the story of his jailer, whom he had befriended during those years in prison. The jailer would bring him extra food, and he’d sometimes send vegetables home with the jailer to take to his wife who had a hard time finding them. Then, after Mandela told us that story, he brought the jailer up to the stage and they embraced. That basically tells you what kind of person Mandela was in his older years.

Fidel Castro attending the inauguration of Nelson Mandela

“I asked to take a photo of Nelson Mandela after we had visited with him at his home”

How did it feel to transition out of politics?

I am so grateful for the opportunity I had to be in public life and to effect change in a number of areas. It was an honor to be part of what I consider to be a public trust. Al felt strongly that a political career is an important form of public service to our nation and, as his partner, I carved out how I could contribute most effectively in my own way. I wouldn’t take it back.

But part of moving on in life is being happy, having new chapters to look forward to, and being satisfied with closing an old chapter. So I don’t miss that earlier part of my life, and am really excited to enjoy the life that I have today.

Part of that, no doubt, has to do with my spiritual upbringing. I was raised in the Episcopalian Church and have always drawn inspiration and sustenance from my faith. It has guided me through every stage of my life. I remain grateful for all of them.

Presidential spouses fulfill important functions in our politics and society. Those roles also carry some gendered assumptions. In what ways do you think those assumptions might (or might not) be challenged now that we have a Second Gentleman, Douglas Emhoff?

I think we are entering a whole new era and it affects the way individuals wish to fulfill the roles of Second Lady or Second Gentleman. Doug Emhoff is planning to teach entertainment law at Georgetown University. Dr. Jill Biden is still teaching students. We are redefining gender roles in our society at large. The younger generations are more accepting of racial, ethnic, and sexual and gender differences and are more committed to practicing equality. Our laws and society need to catch up to the new standards.

In December 2000, you stood graciously by Al Gore’s side as he stated that “partisan rancor must now be put aside” and conceded in an extraordinarily close election that was ultimately decided by the Supreme Court. What are your thoughts today after witnessing our last president trying to undermine an election whose results were not, in fact, in doubt?

Al served in Vietnam, and Bill [Allen, Tipper’s partner] served in Korea. Both have a deep respect for our democracy and our government. My mother’s first husband was an Air Force bomber pilot who was shot down in World War II; his service to our country continues to mean a great deal to our family. When you think of what others have had to sacrifice for our democracy, and when you contrast that with what we saw during the Trump administration, it’s truly shocking.

In your point of view, how have politics evolved since the Clinton administration?

If you want to know the answer, just read the book How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. We have new governance yet our democracy remains under grave threat. You can’t have unity and be bipartisan when one party is committed to total obstruction.

Mitch McConnell, the former Senate majority leader, wouldn’t even put forth a judicial nominee, the moderate Merrick Garland, for a Senate vote. Since then, of course, it’s become even worse. I have nightmares about the January 6 riot attack on our Capitol. I worry about the efforts to destroy the most fundamental institution of our democracy – our electoral system – that set the stage for the attack. But this crisis has been a long time coming and I continue to worry about where it will lead.

In 2020, a lot of Republicans at the boards of elections who were pressured by the then-president to subvert the results did the right thing. But what about next time? Republicans, and not the kind of Republicans I have known, have had this plan for years. They are playing a long game.

How do you think we might resolve some of these challenges?

President Biden is already showing that he is making good decisions in dealing with our collective challenges – such as grappling with the pandemic and seeking to strengthen our democratic institutions and international alliances. He’s working to bring economic relief to Americans who are struggling with food and housing insecurity. He’s bringing in good people at the cabinet and senior-advisor level. He’s made smart executive orders to help all citizens of our nation. He’s doing things at warp speed, and I think we should feel good about the possibilities.

Of course, the direction of our country ought to be unity. We need to repeatedly communicate a message of unity over division. Attacking state officials, undermining confidence in the vote, seeking to disenfranchise voters – this is not who we are. This is not America, and we need to forcefully and immediately return to our democratic principles.

Certainly, we must acknowledge the damage that has been done. There can be no unity without accountability. In any situation where abuse has taken place, whether it’s personal or societal, you need to acknowledge the problem and hold people accountable. But then we have to ask: Where do we want to go? We don’t want to be like this. We want to respect one another, and we need to come together as a country – now more than ever. It’s time to turn the page and move forward.

Of course, it may not be easy. Not only are we dealing with a pandemic, but foreign countries took full advantage of the Trump administration’s lack of leadership. The hacking of government agencies and facilities – all this was made possible by the fact that during the Trump years, so many professionals working in the government were fired or moved around and, in some cases, their jobs were filled by new people who couldn’t do their jobs well. Foreign countries that are hostile to our interests are making inroads in a new kind of war, a cyberwar. They tried to steal our COVID-19 vaccine, for goodness’ sake! Today, the battleground is shifting from conventional warfare to data theft and information warfare.

It’s hard for people to grasp the severity of the dangers and threats that we face, in part because it’s hard to get visuals that you can use to represent these threats. Nevertheless, we need to recognize them and work hard to come together as a nation. Everybody has a role to play in battling misinformation and fear.

Looking back on some of those battles, what have we gained? What have we lost? And where do we stand in those culture wars today?

In the mid-1980s, the United States was a completely different place. Music videos were new. Vinyl records and cassette tapes were the order of the day. My children were young but loved music and watched videos on MTV. Many parents saw the misogyny and violence, especially the violent sexual images that were in the marketplace and visible to young children. I worked on this issue with the National Parent Teacher Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics – organizations that had long been concerned about the effects of violent imagery on children. They were grateful for the support of someone who could serve as the public face of this effort.

Eventually the music industry decided to work with us and to place voluntary labels on their products. A product was only labeled when both the company and the artist were in agreement. But obtaining this labeling system was a struggle. All we wanted was consumer information on the product so that parents of young children could have guidance. We wanted more information, not less, to help the consumer determine what was appropriate to purchase for their family.

And yet we were accused of censorship and worse. It became quite the battle. As the face of this effort, I was cast as a prudish housewife who didn’t like sex. My loudest critics were angry young men who accused me of trying to censor them, which was something I never wanted to do. I came to realize that we had poked a multibillion dollar industry and they didn’t like it at all.

The person who advised me through this process was the late Jack Valenti, who was president of the Motion Picture Association of America and had worked on the ratings system for the movie industry. He was a good friend and, like me, had a deep interest in mental health issues, having founded Woodley House in Washington, D.C. Jack told me, “You don’t start where you want to end up.” It was clever. Through this process we got what we really wanted, which was voluntary labeling.

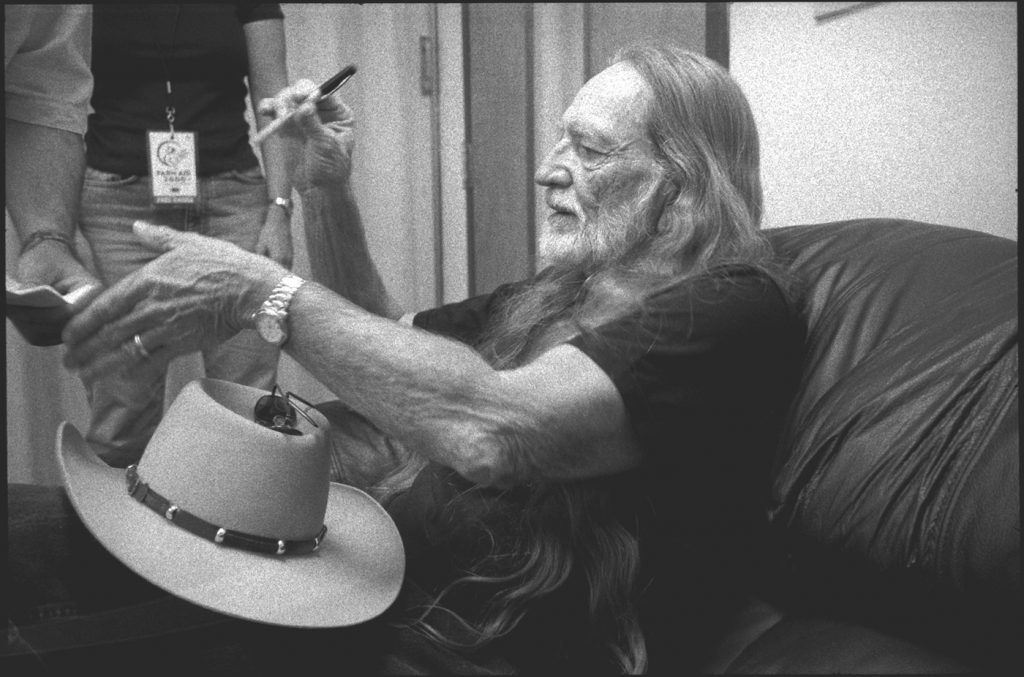

Even today, people who remember that battle sometimes accuse me of hating music. The irony is that I love music! And I know it can be powerful. I used to have an incredible vinyl collection, though over the years my kids have depleted it. I’ve also played drums since high school, when I was a member of the Wildcats, and have continued to play all my life, sitting in with Willie Nelson, Herbie Hancock, and the Grateful Dead. And when Diva Zappa [one of Frank Zappa’s children] made a record, I played the drums.

This leads to a little-known fact, which is that during that battle, you and Frank Zappa became friends.

Frank and I often appeared on TV shows together, each of us explaining our positions. We were on opposing sides. Frank even testified against the Parents Music Resource Center before Congress. One night after we were both on Nightline, we were walking out together and he stopped and said, “Hey, would you like to get a drink?” And I said, “Okay!” We talked and joked and hit it off, and that’s how it started.

We continued to do TV news shows together, each of us representing a different point of view, but everything had changed. Privately, we were friends. Politically, I was living in a bipartisan world at the time, so I was accustomed to getting along with people with whom you have differences of opinion. Frank introduced me to his kids and his wife, Gail, and she and I became dear friends and remained friends after he died.

In fact, in 1999, when the presidential campaign started and I frequently traveled to Los Angeles for events, Gail would invite me to stay with her. And I would. It was so much more pleasant than staying in a hotel. She had this gorgeous guest bedroom, so beautifully decorated, it felt like sinking into a white rose petal. I’d wake up and we’d have a great time chatting. I’d go off and do a campaign thing then come back to her place and chat some more.

At this point during our interview, Tipper is distracted by a fox outside her window that frequently hunts on her property. She gives a low whistle: “Hello, Daisy Mae!” She pauses, then tells me, with a laugh: “She says hello back.” Tipper is clearly at home in the countryside. She shares her affinity for the natural world with her partner, photographer Bill Allen.

You and Bill share a love of photography. Is that part of what drew you together?

Yes. Bill was editor-in-chief of National Geographic Magazine and had spent his career there. Our love of photography brought us together, along with mutual respect, friendship, and an interest in the same things.

We often collaborate on photography projects. A friend invited us to Wyoming to photograph the eclipse in August of 2017. We stayed for four days and brought lots of camera equipment. We set up a table in a meadow in her yard. Bill captured the phases and I shot the full eclipse. We put them together, framed them, and gave the finished series to a few friends who wanted them.

Are there specific cameras you use now?

For the last few years, I’ve used several cameras, including a Nikon D800. I used the D700 for years and got this new one about three or four years ago. In addition to its quality, I like that it’s so easy to use. With my thumb I can work the buttons on the back that change the ISOs, the aperture, the camera speed. It’s so easy to manipulate.

I also work with a Canon and have about three or four lenses. For portraits, my favorite is an 85-mm lens. For photographing an eclipse or an animal far away, I would use a 400-mm lens with an extender that would make it the equivalent of a 560-mm lens. But it’s really heavy. Now I use a tripod with it.

When did you fall in love with Montecito?

In 2010, three of my children were living in Los Angeles, and I wanted to find a place relatively close by. One of them had a friend in Montecito. So one day, we came here for lunch and spent the rest of the day exploring. We visited the pier, the beach, and walked the San Ysidro Trail into the mountains. By the end of the day, I knew that I had fallen hard for Montecito.

I love the two mighty voices in nature: the mountains and the ocean. You have both in Montecito. I also love the privacy and the fact that everyone respects that aspect of living here. I have to admit that I am one of the many part-timers. Two of my children are in California now and two are on the East Coast, but I spend as much of the year as I can in Montecito. I feel a sense of belonging with the community and have made many good friends.

We especially enjoy our Santa Barbara family get-togethers. Everybody in my family loves to hike, so that’s one of the activities we share. We also enjoy our dinners at home. The kids will go to the grocery store and since some of them love to cook, they’ll spend the day preparing all sorts of dishes. When the weather is beautiful, we eat outdoors and linger into the evening.

Some of my favorite spots in Santa Barbara are Santa Claus Beach and Cold Spring Trail. I own a half wetsuit, and some days we’ll head to the beach and swim far enough from the shore that we’re among the dolphins. They’re not afraid and will play around us in the water, which is magical. Currently, I am getting trained in scuba diving with a friend, and while we’ve been somewhat interrupted by the pandemic, our goal is to complete the training then explore the underwater forests just off the Channel Islands. There is so much natural beauty to explore out here. It’s one of the reasons I try to spend as much time as possible in Montecito.

Bison jumping a fence in Jackson, Wyoming;

Autumn in Jackson Hole, Wyoming A dusting of snow on trees in Yellowstone National Park

A dusting of snow on trees in Yellowstone National Park

Tipper and Bill Allen collaborated on photographing the August 2017 eclipse in Wyoming

Do you take a lot of pictures in Santa Barbara?

Yes. Bill and I have taken pictures in the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, on the beaches, up on the hiking trails, and at Lotusland, which we support. We love all the different aspects of the garden, especially the cactus garden in the late afternoon light. Or we just wander around, checking out the ponds when the lotuses are in bloom.

I’ve also taken photographs for Hidden Wings, a Solvang-based group that supports autistic kids and their families. They host a lot of their events at Refugio Beach, such as drumming circles, which the kids really appreciate. My friend Mickey Hart [former drummer of the Grateful Dead] put me in touch with the director, Reverend James Billington, and I’ve been working with the group for a number of years. They use my photographs for their brochures and grant proposals.

One friend who helps Hidden Wings in the most wonderful way is a FedEx driver Rob Kennedy. He’s been one of the group’s mainstays for years. Sometimes Rob will come to the house in Montecito and say to me, “Hey, Jim’s doing some kayaking with the kids at Refugio next Saturday, and he wants to know if you’ll stop by and take some pictures.” It’s nice to have it be so community centered.

In addition to Lotusland and Hidden Wings, are you involved with any other local philanthropic groups or artistic activities?

I’ve worked with a terrific group of people on The Concert Across America to End Gun Violence at the Arlington Theatre. Kenny Loggins, Michael McDonald, the band Ozomatli, and many others have volunteered their musical talents for this cause. I’m also involved with Human Rights Watch, sit on the Santa Barbara committee and am on the board of the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network. These are just a few of the philanthropic activities I’ve been involved with since my move to Santa Barbara.

Would you like to say anything about your advocacy work for mental health, the LGBTQIA+ community, and the homeless?

I was the mental health policy advisor to President Clinton, and I chaired the first White House Conference on Mental Health. One of our goals was to obtain insurance coverage for mental health, equal to that available for physical health. We worked hard for such parity, which our administration started and President Obama completed.

In 1990, I founded Tennessee Voices for Children, which provides mental health services to families. The organization now serves more than 50,000 families each year, and since last year it’s provided more than 1,000 therapy sessions, thanks to many donors.

I also support the National Alliance on Mental Illness, specifically the Ending the Silence programs for high school students, which teach students across the country about mental illness.

What informed your commitment to mental health?

My motherwas a single working mom in an era when that carried a lot of stigma. Perhaps as a consequence, she suffered from periods of depression. Mental health issues were little understood at the time. I wanted to know more and help educate others. That’s why I majored in psychology and got my master’s degree in the same field. My aim at the time was to work with families and children.

Of course, my life took a different turn, but I’ve remained involved in mental health and other issues related to health care. As Second Lady, I attended the first AIDS Walk in Washington, D.C., as well as many others over the years across the country. I continue to advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights and publicly opposed California’s Proposition 8 to ban same-sex marriage. We are all equal, and no one should suffer discrimination.

Homelessness has also been a big focus of your advocacy. What draws you to this issue?

Part of that, I think, is rooted in my spiritual practice. When I see a homeless person I think, There but for the grace of God go I. I take the message about loving thy neighbor to heart.

In addition to working on my books on the homeless, I volunteered for many years on the Health Care for the Homeless van. I loved that work. I was paired with Sister Pat Letke, who worked on the van full-time. We’d drive out and make connections with homeless men and women with the intention of getting them into care. Sometimes we would go out at night to reach the people living on the street. We had some failures, but also many successes.

I think that the key to reaching homeless people with mental health issues is personal connection and consistency. We’d go to the same people week after week until they agreed to come with us back to Christ House, where they’d receive food, shelter, clothing, and medical and mental health treatment. They’d be evaluated to see if some could move on to transitional housing with the goal of helping them move to permanent housing. The program enabled some individuals to find jobs and begin to live independently.

There is so much work to be done today. And there is no shortage of issues that create deep divisions in our society and that threaten to undermine the very nature of our democracy – from widening income disparities to challenges in our education and health care systems to the threats to our environment. But there are so many avenues for positive involvement and meaningful action.

What draws you to focus today on images of nature?

I am drawn to capturing life cycles in nature – my soul is moved by the natural world. I’m drawn to capture the beauty I see in landscapes, flowers, and animals. We’ve created an artificial separation that disconnects us from the natural world unless we actively attempt to overcome it.

There is one picture I made back in 1972. It’s a black-and-white image of a lake in Tennessee that we visited often. My point here is that my current focus on the beauty of nature and the landscape is not new to me. I’ve been returning to these themes for years. But now that I am “retired” I can spend more of my time exploring these themes.

Center Hill Lake in Putnam County, Tennessee. “My kids learned to water ski on this lake as well as camp out.” (below left) “A bit of flooding of the banks of the lake at another time.”

“A bit of flooding of the banks of the lake at another time.”

“Ménage à frog – ah, spring! Huntley Meadows Park in Alexandria, Virginia.”

“Bison on the move in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. This was a bit of a dangerous shot – don’t do this at home.”

What is the role of a photographer in society at a time when some things we take for granted, such as nature and climate, are under threat?

I see the role of the photographer, particularly a photojournalist, as one of communication with the viewer about a reality or an issue that presents a new perspective. I grew up in a period when the nightly images from the Vietnam War galvanized the youth protest movement. The moral question was no longer abstract; it had the power of a visual. Some of the still photos published in newspapers at the time had the same impact. Just as Dorothea Lange’s images communicated the suffering of the Great Depression, there are many examples of images so powerful that they’ve changed people’s minds. Think of how images of police dogs attacking Black people gave purchase to the Civil Rights Movement. Or of Associated Press photographer Nick Ut’s iconic photo of the little girl running down the road after a napalm attack in Vietnam. Images have power, and persuasion through images can change the world.

This applies to nature photography, too. We should seek to capture the natural world and get it out to people so we know what it is that we have to save. For people who grew up in the city, photographs of, say, the Amazon rainforest or the Arctic Circle are key. So when we say, “This is now under threat of development, and this is what’s going to happen if all the trees are cut or if oil is drilled,” people can grasp what is at stake. They can understand that certain actions are going to take away what this world is intended to be.

Do you travel with the aim of capturing images, and if so, what have been some of the most memorable locales?

Images that stay with me include those from the Old Arbat Street in Moscow and the ballet in St. Petersburg, Petra in Jordan and Cairo, Egypt, as well as La Boca, a colorful neighborhood in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

A few years before the pandemic, Bill and I went to Iceland and were entranced by the fabulous landscape. It’s so vastly different from anything in this country, it blew us away. But trying to convey the beauty of Iceland can be frustrating; it’s almost impossible to capture what you’re seeing in a single frame. Bill wants to capture it with a drone, and we are hoping to return to the northwest part of the country. But number one on our post-pandemic list of places to go is New Zealand.

Local young people demonstrating the tango dance in La Boca, Argentina;

Snake charmer in Marrakesh, Morocco

Where do you find your fortitude? And what words of hope do you offer to your children, grandchildren, and future generations to come?

I have three older grandchildren, and six under the age of six. Those six are still filled with the hope of youth and will need the assurance of a bright future. On a personal level, I remain hopeful.

For personal strength, I remember the 23rd Psalm, which starts: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” During tough times I say it over and over and it gives me some peace. Another prayer that is important to me is the Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi. Someone gave me a copy on a piece of parchment, and I had it framed. One way I can help my children and grandchildren now, and in the future, is to remind them of the words:

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

Where there is sadness, joy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.