The Man in the Miramar

In the movie version of this story, we open on a shot of Invictus, a sleek 215-foot yacht with sophisticated, timeless maritime beauty – all six decks of it – replete with a swimming pool, a gym, a theater, nine bedrooms, and an elevator. Of course.

We pull out further to reveal Rick Caruso, the yacht’s owner – a striking, fit, tanned man in his early 60s, dressed to nautical perfection down to his crisp silk pocket square. He is surrounded by his four grown children (ages 21 to 31), his coifed white dog, and Tina, his beautiful and adoring wife of 35 years, and his world looks complete. But there’s more.

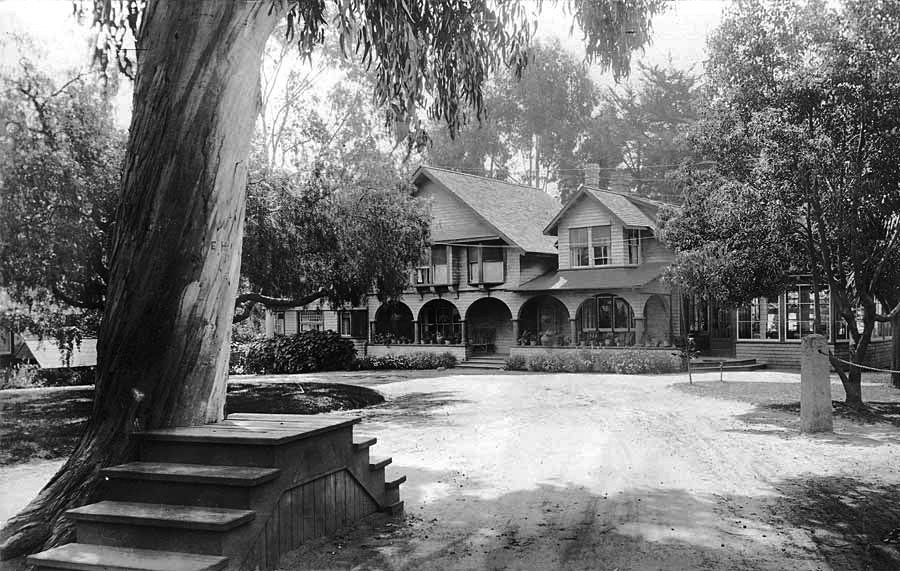

We pull out even further to see that we’re just off the coast of picturesque Montecito, its understated shore lined with centimillionaire surf “shacks” chilling in the shadows of a grand, idyllic beachfront hotel designed – like the yacht in its midst and the man at the helm – to perfection.

However, because this is not a movie, but real life – where this character’s presence has had a profound impact upon Montecito (and Santa Barbara) – we wanted to gain a deeper understanding of the man who infused so much dry powder into our local economy despite our town’s mixed feelings about how the Rosewood Miramar Beach resort’s arrival might have impacted local culture. And if you don’t believe me, ask any retailer or restaurant owner on Coast Village Road.

What we found beneath the surface of Caruso’s polished persona is a surprisingly gritty and strategic civic-minded leader who, against tall odds, has succeeded where other notable hoteliers – such as Ian Schrager and Ty Warner – did not.

But why would that be such a big surprise? Three of Caruso’s shopping centers – The Grove (Los Angeles), The Americana at Brand (Glendale), and Palisades Village (Pacific Palisades) – rank among the top 15 in the country in sales per square foot. So who is this movie star-like, real-life protagonist who could have built anywhere but took on the challenge of a highly problematic rodent-infested site, wedged between a rising ocean, an active railroad track, and a widening 101 freeway? And that was after making it through the labyrinthian gauntlet of the California Coastal Commission, multiple boards of architectural review, and a seemingly interminable permitting process. All the while, turning negatives into positives. A challenging parking situation? Just create an adorable wicker-lined Jolly. There’s a train running through the center of the property? No problem! A Disneyland-esque passageway across the track will do the trick.

It did indeed. And by all accounts, he’s killing it. Just three years after opening its doors (which Caruso claims are never locked), the Miramar is one of the country’s most expensive (and he says most successful) hotels. And from it has flowed a new lifeblood which, by the pandemic’s happenstance, Montecito very much needed.

But the story doesn’t end here. Now, Caruso is taking his I can get s**t done where others have failed attitude back home to Los Angeles, where, as of press time, he is dead serious about throwing his hat in the ring to become Los Angeles’s next mayor.

Will he succeed? It is of course unclear. But what is clear is: One, Rick Caruso is not daunted by big challenges, and two, he should not be underestimated. For a hard-driving entrepreneurial real estate developer turned hotelier known for his connection with elite brands and a fancy, high-end clientele, Caruso is very clear on his priorities – and they just might surprise you.

GL: What don’t people know about you?

RC: Oh, that’s a really tough question. It’s a great question but it’s a tough one. What don’t people know about me? I think that you fall into a bucket if, when you’ve had success, your priorities are different than mine. What I care about most at the end of the day is my wife and kids. I tell my wife multiple times a day how much I love her – we’ve been together for 35 years. I couldn’t talk to my kids more – I talk to them every day. I could lose everything. I thought about that during the pandemic. We were in the center of the bullseye – retail, restaurants, hotel…. I thought a lot about losing everything. And now we’re having our best year ever, which is incredible. But all I cared about was keeping the family safe. I don’t think credit is given when maybe if you’re successful, your priorities are really aligned with what most people’s priorities are, which is their family.

My grandparents were immigrants from Italy and all four sides came through Ellis Island. So there was always a great Italian culture in our home, and there still is today in terms of how we operate as a family. If you want to know about me, you’ll know how dear my family is to me. That’s what I treasure the most. And that’s what motivates me at every one of my properties, including the Miramar. At the Miramar, there are things that celebrate my children. They’re always very subtle and low key, and unless you know they’re there, you probably wouldn’t notice them. For example, if you look at the weathervane on the beach building, it doesn’t say north, south, east, and west, it has the initials of my kids. And they each picked quotes that are engraved in brass and in the stonework on the veranda overlooking the great lawn.

GL: The Miramar was not an easy project to develop, and there had been other strong-willed, experienced developers with great capacity who couldn’t pull it off, but you wanted to do it. Why?

RC: I always wanted to build a hotel or a resort. I always felt we were in the hospitality business anyway. At The Grove or Palisades Village, there’s a concierge and we’re there to serve customers – it’s all about the guest experience. I felt it was a natural extension of what we already did – and honestly, there’s just something very sexy about building a hotel where you have people come and stay with you and you can create this holistic experience. Our core business is always defined by enriching lives.

And we can do that through our retail, our restaurants, our apartments, and our resort. I remember the morning I read that Ian Schrager bought the Miramar. My heart dropped because I thought, Oh my God, I didn’t even know it was on the market. I missed an opportunity. And from then on, I followed it. And then of all the darn things I read Ty Warner bought it and I missed that opportunity. And then when the opportunity came to buy from Ty, obviously I did.

I don’t think you can find a more beautiful property than the Miramar. And I really don’t think you can find a more beautiful community than Montecito. I love so many places in the world, but the reality is Montecito is one of the most unique and beautiful communities in the world. And so how could I not want to do something with this property?

GL: How do you think the Miramar has impacted Montecito?

RC: I think people who live in Montecito are obviously better judges of that than I am, but what I hope is that we enrich people’s lives on a daily basis. We’re happy it’s a place where people can go, and if nothing else, just sit in a chair, read the paper, and enjoy its beauty to make their day better.

GL: I don’t think I’m the first to notice that the vibe in Montecito has changed over the past few years. It feels a little fancier – more celebrities, royalty, more flash. Is this a result of the Miramar?

RC: I think it has tapped into a culture in the community that maybe we unleashed a bit more. And I always talked about it when we were going through the entitlement process – that the resort is going to be a place where you’re going to be as comfortable walking through the lobby in a bathing suit during the day as you will be wearing a beautiful blazer while going to dinner at night. There’s a chic, casual, comfortable elegance I feel Montecito always had. It never tries too hard because it doesn’t have to – it’s not showy. You don’t need to prove anything. I think we’ve tapped into a culture that hopefully aligns with the values and the priorities of the people who live in Montecito. And I also think it’s aspirational for people who come from different parts of the world to visit the Miramar and Montecito and say, “I wish we lived here.”

GL: Well, aspirational would be one way to describe a $4,000 cotton sweater at Brunello Cucinelli. [I’m only half joking with Mr. Caruso when I raise the issue of the prices of ultra high-end luxury brands sold in the Miramar’s stores, because one of the things about Montecito I have appreciated is that you didn’t see a lot of name brands parading down Coast Village Road.] There has always been an understatedness to the wealth in our community, so this shift feels like a real change. That’s not just the Miramar; there are many new people who have moved into the community since the pandemic. But stores such as Dior, Brunello Cucinelli, and Goop certainly signal – if not endorse – a new vibe, don’t you think?

RC: I personally don’t view that as a bad thing. I think people in Montecito now probably have more options of where to shop and how to dress and how they want to express themselves – I think it’s a healthy thing. But it does go back to my earlier point that I think there is a low-key, subtle elegance to Montecito. I don’t see that changing. It may be expressed a little bit differently from time to time – somebody buying a Gucci bag and walking through town – but I think Montecito is going to continue to evolve because you do have a lot of new people in town.

GL: High-end brands aside, does the Miramar make money?

RC: It does very well – it’s probably the most successful hotel in the United States right now. By far, in fact. It’s funny you ask that question. I remember when I was going through the entitlements, people said, “You’re never going to make any money, you’re going to lose a lot of money.” I wasn’t in this for charity. This was not part of my charity work. It’s a very profitable hotel.

GL: Do you have plans to buy a house in Montecito?

RC: We built a private residence on the grounds at the Miramar. It’s a perfect setup because we get to enjoy the property and experience everything our guests experience yet we still have our privacy.

GL: You’ve been a champion of small businesses for a long time. And you worked on state and national level task forces, including Gavin Newsom’s business and jobs recovery task force during the pandemic. What advice could you give to Santa Barbara regarding its attempt to renew State Street and to rebuild its small business strength?

RC: It’s complicated because there’s a lot of impact on State Street. You have issues with the homeless, you have issues with crime, and you have an incredible street with a really glorious history to it. I think every city, not just Santa Barbara, needs to create – for lack of a better term – “opportunity zones” for small businesses, where fees are waived and local taxes may be reduced in a way to help local businesses grow. And then once they get to a certain size, you can peel that stuff away. But I believe the backbone of any great city is the small businesses – the small restaurants, the entrepreneurs, the local stores. And that applies to Montecito on Coast Village Road, the Upper Village, and to State Street.

Small businesses were so hurt during the pandemic. One of many things I’m proud of with my company and my team is that our goal was to get through the pandemic and bring everybody across the bridge with us – our employees, our families, and our retailers. And to do that, it had to be an enterprise where I was contributing money to support small businesses. Our bigger retailers were paying rent in order to be part of the whole system, and we didn’t lose anybody. To this day, there are small businesses on our properties that still don’t pay rent because we want them to regain a firm footing. I think that’s critically important.

GL: You’ve been widely recognized not just for your business innovations but your philanthropy in the Los Angeles community as well. You’ve endowed the Our Savior Parish & USC Caruso Catholic Center; you chair the board of trustees of USC; you also serve on the board of visitors of the Pepperdine Caruso School of Law, the board of trustees of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation & Institute, and the boards of Para Los Niños, St. John’s Health Center Foundation, and The California Medical Center. And you and your wife, Tina, founded the Caruso Family Foundation, which is dedicated to supporting organizations that improve the lives of children in need of healthcare and education. Clearly giving back is a priority for you. Why?

RC: There are so many things that help shape you. And as a young child with immigrant grandparents who had nothing, it always amazed me by how generous they were. And they always drilled into my head that my job – all our jobs – is to work hard for the next generation, give back, and bring people along with you. There’s always room at the table, and I live my life that way. We’re always here to help people in need. So the philanthropies we care about the most and we fund the most involve families – in particular children who have very little, are typically living below the poverty level, who don’t have access to education or healthcare, and who live in very tough conditions. We’re very proud of the fact that it’s not just about writing a check, but also about getting to know them and getting our hands dirty helping and working with them. All of my kids work on Skid Row in Los Angeles. They work at Operation Progress at the Nickerson Gardens and in the projects where these wonderful families live.

My daughter started a program called the Angel Riders where she brings young kids living in the inner city who have never been around a horse and gets them on horseback. Obviously, faith is a big part of it because she was raised Catholic. I think every faith is about being generous and working for others. And that philosophy also informs what we build, why we build, and our connection to the community. Every one of our properties is always open – there are no guards or gates – none have hours for a reason, and they are available to every walk of life. I think this is a wonderful way to celebrate life.

GL: Your family gives back quite a bit in Los Angeles. Do you plan to get more involved with philanthropy in Santa Barbara?

RC:Absolutely. When we had the terrible mudslides, we gave heavily to Santa Barbara through the American Red Cross. They needed everything; they were not prepared. And then at the Miramar, at the onset of the pandemic, we quickly branded a food truck, and every single day, we provided breakfast for the firefighters, police officers, and the rescuers. We’ve done a lot in Santa Barbara and Montecito and we’re prepared to do more. It’s an important community for us.

GL: So let’s discuss the elephant in the room. Are you running for mayor of Los Angeles?

RC: I’m certainly thinking about it – very seriously. For the past year, we’ve had a team that’s been doing a lot of research and work. It’s clearly the direction I’m heading. A dear friend asked me: “Why the hell would you do this? It’s a tough job.” Although it sounds corny, the truth is: I love Los Angeles. I raised my family here, I have my business here, my employees live here, yet there are problems that need to be fixed. The question was, “Why are you choosing to do this?” And I really don’t think I have a choice; I feel I have a duty to give back.

GL: You’re obviously not doing it for the money…

RC: I’m definitely not doing it for the money, nor am I doing it for a career change. I don’t want to run for governor. I don’t want to go anywhere else. I want to come in. If I do serve as mayor, I’ll redirect some things, solve a bunch of problems, and then come back to private life and hang out at the Miramar.

GL: As former president of the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners, what are your thoughts about this complicated moment in our country?

RC: You’re right – it is a complicated moment. Crime is out of control, homelessness is out of control. And I look at it this way: We have a very wealthy city in a very wealthy state in a very wealthy country. And nobody should be living on our streets or under a freeway overpass in a tent. It’s not right. It’s inhumane. And that then affects communities and people trying to raise their kids and run a business. There’s nothing good about it, and it can be solved. It’s complicated, but I think it’s going to take somebody who’s not worried about getting reelected, somebody who is liberated from that and can say, “This is the right thing to do. We’re just going to do it.”

GL: What does that look like? Homelessness is like a giant octopus with each of its arms representing a different aspect of the issue. There’s mental health, the lack of affordable housing, addiction, income inequality…. These issues are not unique to L.A. yet no one’s cracked them. How do you plan to bring people together to solve this problem?

RC: This isn’t a bold decision I’m making in the midst of a crisis; many cities like L.A. are in the midst of a crisis. No one can solve it alone – it takes strong leadership, getting people to follow you, then putting a stake in the ground and saying, “We are going to do this.” I don’t think the formula of big committees solving problems works. We’ve been doing that for too long and the problem has only gotten worse. You have to build shelters quickly to get people off the streets. You have to have services for mental health and services to retrain people. This kills me, but do you know the largest growing population of homeless are the elderly? So we now have seniors becoming homeless at a faster rate than anyone else. What kind of society puts their seniors on the street? And you can’t tell me they want to be there. So yes. This problem can be fixed. I’m not on a bunch of committees, I don’t spend my time doing that. I surround myself with really smart people and give them a lot of tools to do their job.

GL: At one point you were the youngest commissioner in the history of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. So in terms of water and sustainability, based on the LA100 study, Mayor Garcetti announced the department of water and power will pursue an 80 percent renewable and 97 percent carbon-free grid by 2030 as well as 100 percent carbon-free energy by 2035. That was, I guess, 10 years ahead of schedule. Would you make a similar commitment?

RC: When I was a commissioner at DWP, I was the one who took all of these coal plants in the L.A. basin and converted them to gas to reduce emissions. And I was the one who oversaw the building of Palo Verde Generating Station (a nuclear plant in Arizona) to bring in clean power. And I was the one who settled the water war in L.A. County. So I understand water and power.

I think goals are great. What I would say to Eric [Garcetti] is, “Give us your plan on how to get there.” It’s really easy – set a goal. And yes, sustainability is very important to me, it always has been. We want to have a clean basin and we want to have sustainable policies in place. But you have to have a real plan. And then you have to say, “What is the cost of that plan for the average resident?” Because a big chunk of people’s paychecks go toward their utility bills. So there is a balance, but yes, I am committed to sustainability.

GL: Does the Miramar live up to this standard of environmental stewardship?

RC: Absolutely. The Miramar is one of the most sustainable properties we have – down to how we do laundry. There are no plastic water bottles, everything is in a metal bottle. Reusability is really a model of sustainability.

GL: You’re a guy who builds luxurious experiences. And while anyone could go sit and have a drink in the gorgeous bar at the Miramar and not pay $2,500 (or in some cases $13,000) per night to be a guest in one of the oceanfront rooms, your brand is – in all ways – elite. Are you prepared for the blowback against you as something of a poster child for “the good life” asking to lead a community effort to solve problems such as extreme poverty, wealth inequality, racial inequity, and inclusion? How are you prepared to counter charges of elitism that will come your way?

RC: I think it’s a great question, and I’ll answer it a couple of ways. What was more exclusionary was when the property sat vacant for 15 years with a chain-link fence around it. The beach was dirty and you couldn’t get down to it because there was a gate with a lock on it – and only a few people had the key. Now anybody can safely walk through the property and enjoy the beach.

The other thing I would tell you is because of our charities, I live a big part of my life in the poorest parts of Los Angeles – and so do my children. I didn’t grow up rich in the beginning. I know what it’s like to see these kids at St. Lawrence of Brindisi School in Watts and what they go through – the gunshot drills and they’re running back to their classrooms. I know what it takes for a young man who goes to the high school down in Watts, walking from Nickerson Gardens and being teased by the gangs for going to Verbum Dei because you have to wear a black tie and a white shirt. I’ve sat in the classroom with those kids and I know their parents. I understand it really well. What I don’t understand is being a pompous legislator who thinks they have all the answers yet actually has never experienced it. And has actually never signed the front of a check – only the back. And you know there isn’t an elected official in the United States who had a pay cut during the pandemic whereas most every other worker did.

GL: You say you didn’t grow up rich, but your parents owned Dollar Car Rental, didn’t they?

RC: My dad did, but not until well after I was born. My dad became a very successful businessman, but we weren’t raised that way in the beginning.

GL: You serve as chair of the board of trustees for USC, which has gone through some turmoil in the last few years. (One of the most corrupt university administrations of higher education saw an overdosed prostitute in a hotel room, an FBI sting of a basketball coach, disturbing sexual abuse allegations and cover-ups, a shockingly blatant influence-peddling scheme including a central role in the massive college admissions scandal, and, most recently, the announcement of federal corruption charges against L.A. City Council member Mark Ridley-Thomas and a former dean at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.) Are there lessons learned here you would apply to your leadership in Los Angeles?

RC: Oh yeah. Many. Listen, accountability matters, integrity matters, leadership matters, making decisions quickly, not letting things brew. But the biggest problems at USC were the priorities were wrong, there was no accountability, and things got swept under the rug. We changed that culture with a lot of help from many good people on the board of trustees along with new leadership. It’s a different place today, and I’m very proud of the progress that’s been made there.

Intentionality can be found in all corners of Caruso’s life. So I wondered why he named his yacht – perhaps the most conspicuous symbol of his vaunted life – Invictus.

GL: Why is the name of your yacht Invictus?

RC: It’s named after the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley. It’s the story of the struggles of life and eventually getting to heaven to get through the gates. And when you read the poem, it’s about how you get battered and bloodied and bruised, but you become the master of your faith and the captain of your soul. If you stay true to what you believe in and try to do the right thing, you get through the gates, even though you’re going to be a little bit beat up. That’s the philosophy I and my family live by.

GL: As Caruso leaves me with those poignant words, I reflect upon the words that originally inspired him:

Invictus

By William Ernest Henley

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

GL: For fun, I look up the word invictus, which,

as it turns out, is Latin for unconquered

or undefeated. Suddenly, it all makes sense.

You must be logged in to post a comment.