Viva Community Chorus and La Primavera

In 1919, Santa Barbarans had learned to work together for the war effort, and the time was ripe for a new era to begin, one that would start with the formation of a community chorus and blossom into a cultural renaissance.

The community chorus idea had been borne of the idealism of the Progressive Era and strove to bring about a democratic music that would bind people of all classes together with unified purpose and spirit. Probably the greatest visionary advocating a new era in which cultivated American music would be produced and available to all, was composer, conductor, and ethnomusicologist Arthur Farwell.

In 1913, Farwell had teamed up with Harry Barnhart, a choral director known for charismatic song leading, and the principles of the Community Chorus movement were born. They believed that the primary goal of such a chorus was for the emotional, intellectual, and spiritual unification of a community, so the artistic quality of the chorus was of lesser importance. All people, not just those schooled in music, could sing and experience the transcending power of communal spirit.

Arthur Farwell Comes to Santa Barbara

Between 1910 and 1920, the population of Santa Barbara had nearly doubled to 20,000 residents. Among that increase was a large cadre of talented, cultured people of means who had succumbed to the beauty of Santa Barbara’s natural environment and salubrious climate and had been charmed by its historic Spanish past. With the end of World War I, it was time to rebuild cherished institutions, and increasingly, it was the influence of these newcomers who were to usher in a new Golden Age of Culture in Santa Barbara.

In late September 1919, The Morning Press announced that Arthur Farwell, a composer, poet, conductor of community choruses, pageant organizer and director, was coming to speak at the Recreation Center. He had been invited by a group of civic-minded citizens, led by nationally known poet, playwright, and suffragist Marion Craig Wentworth, to create a community chorus for Santa Barbara.

Upon hearing of his impending arrival, society editor Jessie Mary Bryant recalled a conversation she had once had with David Mannes, the violin virtuoso. Mannes had said that only a common love of beauty would bring about universal peace; laws and agreements between men and diplomatic activity would not help us attain it.

“He meant,” said Bryant, “all thing lovely: music, drama, pageantry, painting, sculpture, the beauties of nature, the fineness of mankind, the love of loveliness itself.”

Farwell promised to get the ball rolling on this premise.

At the Recreation Center meeting, Farwell said that song was the origin and foundation of all other music.

“Through the community chorus, many pageants, entertainments and patriotic gatherings can be arranged to furnish Santa Barbara with the best of musical numbers and instill in the people a love of art, such as no other method can do,” said Farwell.

The University of California at Berkeley had hired Farwell to direct their music programs, but he planned to come to Santa Barbara once a week to establish the community chorus. Week after week the number of participants in the Community Chorus grew. At the second meeting, Farwell showed those who didn’t consider themselves singers that with a little instruction they could make real music. By November, the press reported that the musical people in Santa Barbara were all agog over Farwell’s successful leadership of the community chorus. By the end of November, the Community Chorus was ready to give a public program at Plaza del Mar.

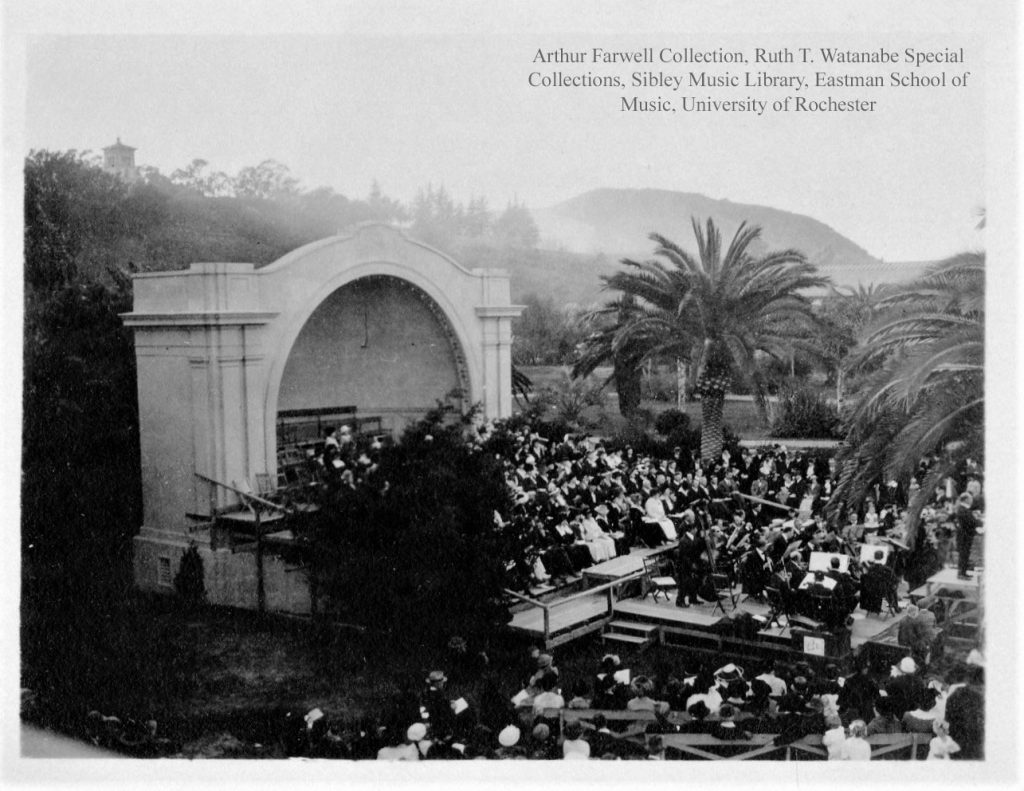

Some 2,000 people gathered at Plaza del Mar that Sunday. Song sheets were circulated, and everyone was urged to take part. “Those who had come merely to listen,” reported the newspaper, “found themselves drawn-in irresistibly to the current of the music.”

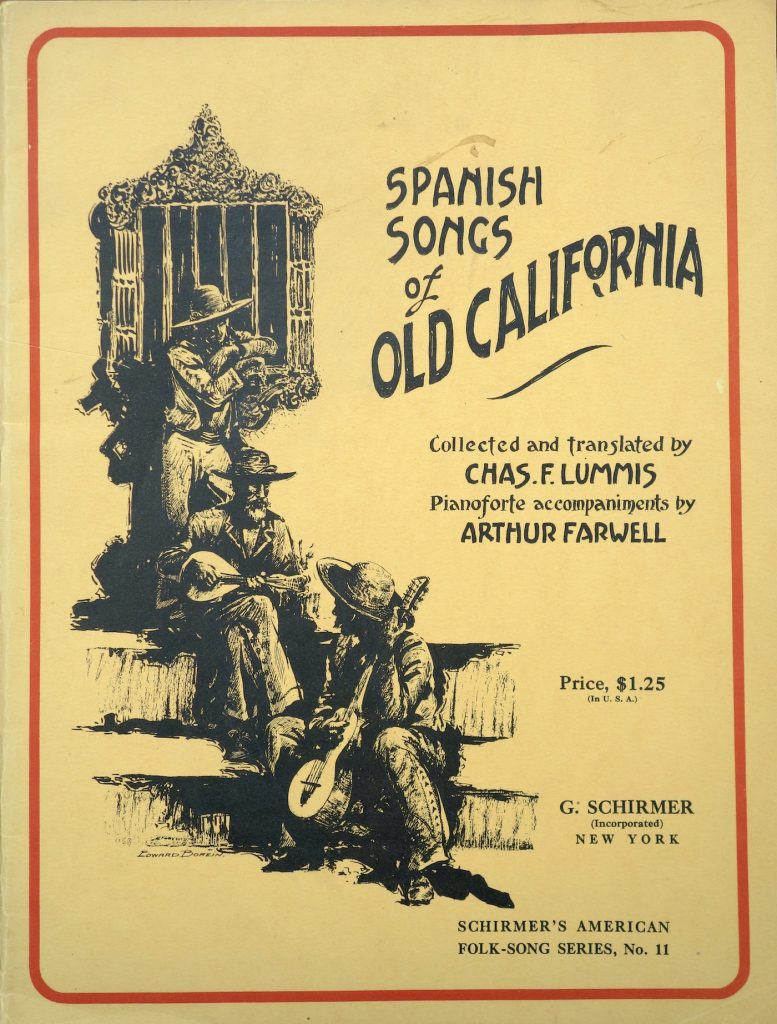

As Christmas approached, the chorus continued to swell in size. For their Christmas program on December 28 at Plaza del Mar, an orchestra of 30 musicians from Los Angeles was to play. The program included a section devoted to Spanish-Californian songs, for which Farwell had created special orchestration. The press claimed this would be the first time such songs were to be included in such a concert anywhere in America. As the Community Chorus moved forward, the preservation of Spanish music became an important element.

The December concert broke all records for attendance, and the chorus had grown to 500 strong voices. The Morning Press reported, “To think that several hundred people, many of them without musical knowledge, could be brought together and welded into a chorus that would reach such magnitude seems almost incomprehensible.”

Three-thousand people joined in and were entertained by Spanish songs, Christmas carols and the heavier works of Handel, Haydn, Wagner, and Gounod. With the Community Chorus well on its way, Farwell’s prediction that people singing together would lead to orchestration to support and accompany them, which would then lead to the presentation of beautiful community forms of spectacle and drama, came to pass.

Preparations for La Primavera

Also in September 1919, business and civic leaders in Santa Barbara decided to create an annual festival based on Santa Barbara’s historic Spanish past. They hoped such a festival would bring thousands of people to town on an annual basis. They called it La Primavera. Wallace Rice, author and playwright, was hired to write the masque (pageant), Samuel J. Hume, director of the Greek Theater at U.C. Berkeley, served as director, and Farwell was director of music. It was to be a community event and hundreds of locals were recruited to take on roles for the telling of Santa Barbara’s history. Irving Pichel, actor and assistant to Hume at Berkeley, was hired to play the narrator.

Music for the masque was collected by Laurence Adler, music director and choirmaster of the Deane School in Montecito. Like Farwell and Charles F. Lummis in Los Angeles, Adler had been collecting early Californian, Indian, and Spanish music, much of which was composed in Santa Barbara. A newcomer from Lake Forest, Illinois, Hobart Chatfield-Taylor, novelist and biographer, said that the quaint old Spanish music learned from old time Spanish residents and recorded for use in the play would be a means of preserving some of the sweetest of Spanish ballads. Chatfield-Taylor was a great cultural promoter and had brought Wallace Rice to Santa Barbara.

As plans progressed, there was an excitement in the air, and several community members were urging a movement to create a community theatre and art center to bring together all aspects of the arts.

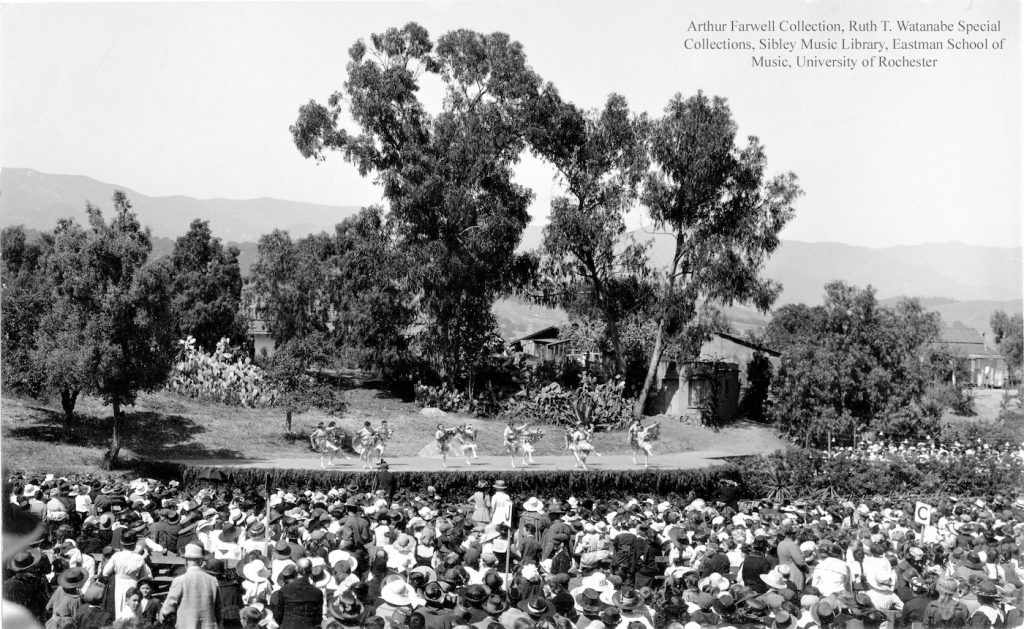

The site selected for the spectacle was in a draw between Canon Perdido and De la Guerra streets, just beyond Neighborhood House (the old Arellanes Adobe) and north of Garden Street. Four-thousand seats were installed in the swale in front of the 80-foot stage built against the rising hillside.

Viva La Primavera

When April 28, 1920, finally arrived, weeks of promotion had done their work. The following day’s headline blared, “PAGEANT MASQUE LA PRIMAVERA SHATTERS ALL PRECEDENTS IN SANTA BARBARA CELEBRATIONS.” Record-breaking crowds attended the two performances, which opened with a prologue by El Barbareño (Irving Pichel), who intoned, “Sweet ladies, genial gentlemen; this day glittereth like a jewel brightly placed. So come we hither to call back the Past when smiling nature at her kindliest ruled this newer Eden. Such ancient things ye’ll see; but chiefly amidst our birds and flowers and butterflies, bright Primavera, spirit of this place, forever young, with blossomy dancing months (of May).”

The parade of history begins when Primavera says, “I hear the footfalls on my foam-laced strand of newer fates.” These fates come in the form of the explorers Cabrillo and Vizcaino and then the missionaries who brought Christianity to the Chumash people. When an ancient pagan idol is thrown out, it returns as a duende, a corrupting trickster who causes strife throughout the years.

In Act II, Spain yields to Mexico, and in Act III Mexico yields to the United States. Throughout both acts, singing, music and dancing predominate. The well-known Santa Barbara story of the lost canon (Canon Perdido Street) is portrayed. And wouldn’t you know it, it was the duende who made those boys steal that American canon.

The play, such as it was, ended with the commandante’s daughter marrying the American officer who had collected the 500 (Quinentos Street) pesos penalty for the theft.

At this point the play is essentially over and the Spanish dances of El Son, La Jota and La Contradanza lead to a grand finale danced by the entire cast to the singing of the choristers and the music of the orchestra. As the actors and dancers leave the stage, the American flag is raised, and everyone stands to sing the “Star Spangled Banner.”

An elated Santa Barbara heaped praise on the spectacle performance, which was a rousing success. Unfortunately, it was a financial failure. In June, the organization sent out letters to its guarantors saying they had a deficiency of $10,000 and that each investor needed to pay his share. Though La Primavera organization stayed around for a few more years, they were never able to launch such a spectacle again.

At the beginning of December 1920, there was another disappointment for Santa Barbara; Arthur Farwell announced his resignation from the direction of the Community Chorus due to lack of support and the lure of work elsewhere. Nevertheless, La Primavera and the Community Chorus had lasting impacts on Santa Barbara by leading directly to the establishment of the Community Arts Association and ushering in a golden age of culture. (A complete history of the development of the Community Arts Association will be found in a future Noticias, the publication of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum.) •MJ

Sources: Contemporary newspapers; Stoner, Thomas. “‘The New Gospel of Music’: Arthur Farwell’s Vision of Democratic Music in America.” American Music, vol. 9, no. 2, 1991, pp. 183–208. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3051816. Accessed 3 June 2021; La Primavera by Wallace Rice; Special thanks to Gail E. Lowther, Special Collections Assistant, Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester, for photos.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.