Tale of the Hobo Artist: John Dwight Bridge Enters Existential Crisis That Leads Him Around the World

In the early 1920s, the artist John Dwight Bridge was a popular and important force in the cultural renaissance fostered by the Community Arts Association. Having proven himself in earlier productions of the Community Arts Players, he may have reached his apex when he took on the role of Nicola, the Bulgarian manservant in George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man.

It played at the Potter Theatre on March 11, 1922 and received glowing remarks from Morning Press reviewer Sarah Redington. About Dwight she wrote, “Well, if I were a matinee girl, I should say gushingly that he was just too lovely for anything in the world. He really was. That costume! That wig! The way he shambled across the stage! And it wasn’t just farcical, for, he made the audience feel that he was a real Bulgarian peasant grown of the soil, and with all the characteristics of his untamed people.”

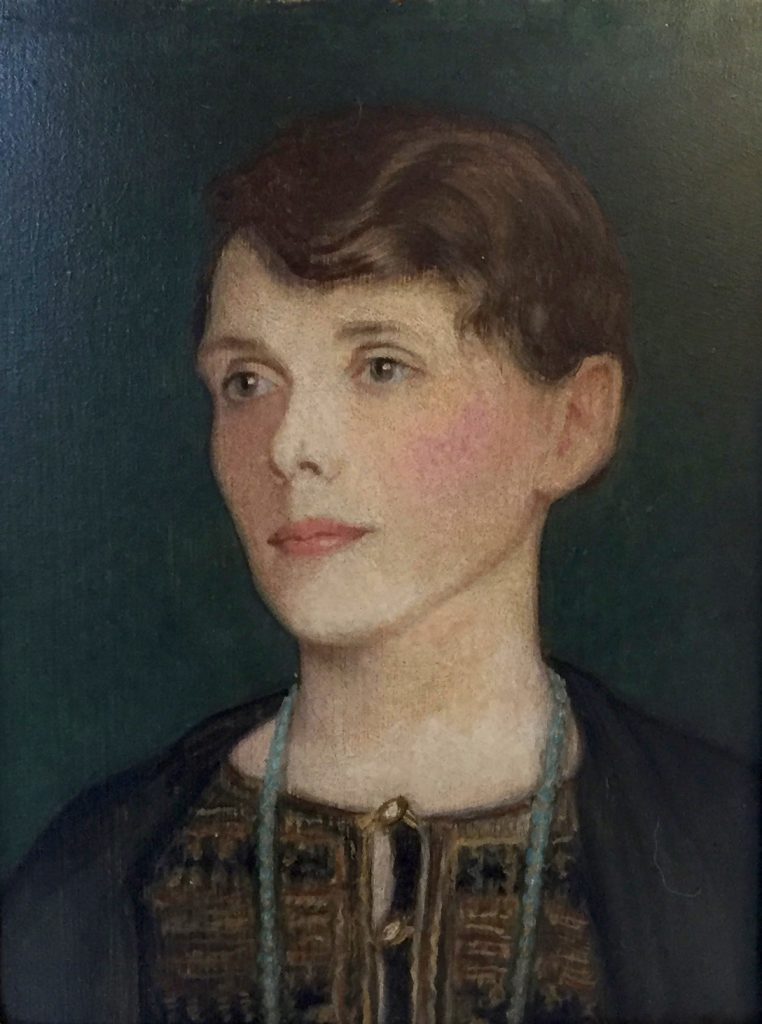

But Dwight was primarily an artist, and 1922 saw his rise in that regard on the Santa Barbara scene. When the School of the Arts opened its gallery, Dwight’s painting, Portrait of the Lady, was considered “Sargentesque” in its perfect portrayal of character.

“Those who know Mrs. Bridge, whose portrait it is, declare it marvelous, while those who do not know her, will be arrested by the charm of its warm human quality,” wrote the reporter for the Morning Press.

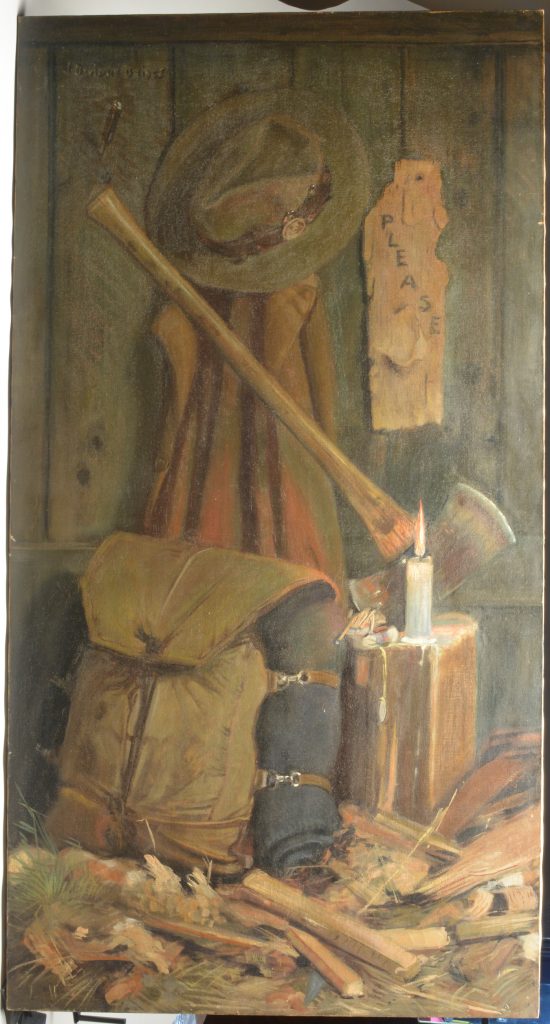

A later article on Dwight said, “(He) is a young artist of extraordinary genius and ability. His work is mostly in the portrait line, but there are in his studio a number of still life pictures that show rare merit.

“The portrait of Everit Herter, the three-year-old son of Mrs. Bridge, is a veritable delight. The blue eyes and golden hair, in connection with the radiant child face, combine to make a picture of rare beauty… One of Mr. Bridge’s best pieces of work, so his friends declare, is his portrait of Miss Lolita Armour, painted prior to her marriage, last June, to John J. Mitchell, Jr.

“This artist has already done a large amount of work and has made an excellent start on his road to fame. Dearly in love with his art, and with the happy combination of youth allied with energy and boundless ambition, it seems only reasonable to prophesy for him a career of brilliant achievement.”

By 1922, Dwight had moved to the Meridian Studios on De la Guerra Street, and in October their second son, David, was born. The Bridges soon began to travel extensively to summer abodes elsewhere and visit family in St. Louis and East Hampton. In 1924, they spent a month or more in Europe.

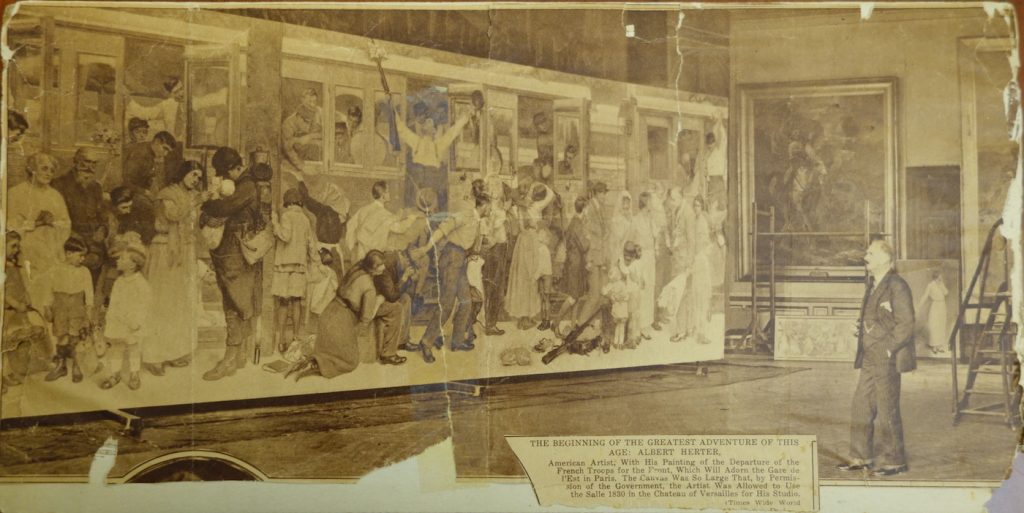

The Departure of Troops from Gare de l’Est

In January 1925, the French government asked Albert Herter to create a monumental mural to commemorate the French sacrifice during WWI. It would also be a memorial to his son, Everit, who had died at Château-Thierry in 1918. Albert was given Salle 1830 in the Palace of Versailles to paint the enormous 15-by-40-foot canvas, which was to hang at Gare de l’Est in Paris, the train station from which so many troops had departed for the front.

In May 1925, the entire Bridge family moved to Paris so Dwight could work as Albert’s principal assistant. It was exacting work made especially difficult when winter approached.

In En Souvenir, his chapter for Portraits of Remembrance: Painting, Memory, and the First World War, historian Mark Levitch writes, “The light was poor and the room so cold and drafty that Herter, Bridge, and another assistant had to wear layers of clothes under heavy jackets and drink rum to keep warm.”

Rum notwithstanding, Albert created a deeply moving and illuminating scene entitled Le Départ des Poilus, Août 1914 (The Departure of Troops from Gare de l’Est). It was full of pathos and human emotion, and in one corner included images of the Herter family among the people on the platform saying goodbye to loved ones.

Vagabond on the Road

By the late 1920s, Dwight and Caroline’s marriage was unraveling, but they both worked behind the scenes for Albert Herter’s last theatrical gift to the people of Santa Barbara, The Gift of Eternal Life. The extravagant production, starring Herter, Ruth St. Denis and David Imboden, opened March 21, 1929, at the Lobero Theatre. Caroline played one of the winged Devas, which are divine celestial beings.

By 1930, however, Dwight was back in St. Louis hosting an exhibit of his work at the Coronado Hotel. He also spent several weeks in Dayton, Ohio, to paint portraits. The review of his painting of Joseph Dart, Jr., manager of West Virginia coal mines, was glowing.

“Mr. Bridge has caught the youthfulness of the eyes… A palatable looking drink half fills a glass in the right hand while a half-burned cigarette is in the other hand, and the naturalness of the pose is remarkable.”

Caroline, meanwhile, had become a partner in a gift store called Cosas del Hogar in Santa Barbara’s El Paseo complex. For all intents and purposes, the marriage was over.

In 1933, professing that he wanted no part of money he hadn’t earned, Dwight divorced Caroline and gave her the entirety of his inheritance. In that year, Caroline moved to Ojai.

Dwight had also begun to question the true value of his art. He believed the enormous prices he was getting were based more on the élan of his inherited wealth, his elegant New York apartment, and the expensive parties that he gave rather than on the merit of his art. He felt that inheriting great wealth was a great obstruction and stifled self-actualization.

“I’m going to give my fortune away and prove that an ‘impractical artist,’ without one cent of money, can work his way around the world and live well besides,” he declared.

He wanted to see what prices his art would fetch if he were an unknown artist, so on March 10, 1933, he ended up on the rail platform in Salina where he disposed of the little money he had left and began his endeavor to test his mettle and work his way around the world.

After the first day spent walking and drawing portraits in exchange for food and lodging, he hitched a ride to Denver. Unable to get work there, he borrowed $10 from a friend to get to Colorado Springs where he found work painting doors and window sashes for $6. News of his unique adventure got out, and the local newshounds descended.

Publicity brought him a commission to paint a $200 portrait (the going rate in New York had been $2,000). He used the money to buy a plane ticket to California where he visited his sons and managed to get enough portrait work to pay his first-class passage to Honolulu. There he stayed with fellow WWI camouflager William Twigg-Smith and his wife. The Hawaiians were less impressed with his story, however, and business was slim, so he only had enough money for a third-class ticket to Yokohama, Japan.

When he arrived, the Japanese authorities arrested him for having no money and deported him to Shanghai, which they considered “the port of all good tramps.” There he met a friend from St. Louis who arranged for Dwight to paint a portrait of Judge Purdy of the American Court in China. The painting was exhibited at the American Club there, and soon commissions for portraits flowed in.

With the exception of one portrait, however, that of Mrs. Luther Chang, sister-in-law of the Chinese minister in Shanghai, they were all of Americans living in China. He was able to raise his prices to $500 per painting and moved into a luxurious suite at the Metropole Hotel in Shanghai and hired a servant. He was also allowed back into Japan.

Hitchhiking Hobo

In December 1933, Dwight was able to buy a first-class ticket back to the United States. In an interview with a St. Louis newspaper, he expounded on his theories about money.

“To have more than $300 at a time just complicates life, and I detest complications,” he explained. “I’m what might be called a hobo artist, an itinerant painter, who paints where he goes.”

For the next several years, Dwight traveled by hitchhiking from town to town and sought work painting portraits. Before leaving a place, he would either spend all the money he made on commissions or give it away. His baggage consisted of only a toothbrush, razor, passport, diary, and corn-cob pipe. He shaved every three days because a rough looking beard decreased his chance of getting a lift. He slept in haystacks, trucks, Salvation Army quarters, jails, barns, and, when he was flush, luxurious hotels.

For meals, Dwight went to the nearest hamburger stand or restaurant and offered to clean up or wash dishes for a meal, always asking for less than he needed and doing more work than was actually expected of him. Family stories say that if he ever had to run out on a bill, he’d send the money later with the earnings from the next commission.

Dwight continued the vagabond life until WWII, when he rejoined the armed forces as a camouflager for the AAF. He was wounded and spent a great deal of time in hospitals in Palm Beach, Florida. While there, he drew more than 130 portraits of doctors, nurses, staff, and other patients.

His vagabond days seemed to be behind him, though he continued to take on commissions to paint portraits. In 1954, for instance, Carroll S. Alden, retired professor of the U.S. Naval Academy, wrote Dwight a laudatory letter for the portrait he had painted of him. Alden said that the whole family, “seem to find real life in the painting.”

“Of course, as the subject,” Alden wrote, “I am not a competent judge; if, however, you are interested in my own opinion, the portrait is unmistakably similar to what I have often seen in the mirror, though somewhat idealized… I am grateful to you for your careful work and I thank you for making the sittings, never prolonged or tedious, really delightful occasions.”

John Dwight Bridge, the hobo artist, died in Palm Beach in 1974.

Editor’s note: The following sources were used in this report: Ancestry.com resources; newspaper articles at Santa Barbara Historical Museum and newspapers.com; Community Arts Association drama programs; Massachusetts Historical Society – Herter Collection; Blog by Lynn Bridge; “Camoupedia” by Roy R. Behrens, blog; “Santa Barbara School of the Arts,” Noticias, Vol XL. Nos. 3,4, 1994; “En Souvenir” by Mark Levitch, 2020, Portraits of Remembrance: Painting, Memory, and the First World War; and M.A. DeWolfe’s Memoirs of the Harvard Dead in the War Against Germany; vol. 3, pp. 229-247. Many thanks to Caroline Bridge Armstrong; Mike Stevenson of Guyette & Deeter, Inc.; Alan Fausel, executive director of the American Kennel Club’s Museum of the Dog; and Chris Ervin of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum.

Ms Beresford is a local historian who has written two Noticias for the Santa Barbara Historical Museum as well as authored two books. One, The Way It Was: Santa Barbara Comes of Age, is a collection of articles written for the Montecito Journal. The other, Celebrating CAMA’s Centennial, is the fascinating story of Santa Barbara’s Community Arts Music Association.

You must be logged in to post a comment.