He Landed Safely

My longtime friend and confidante, balloonist, scientist, physicist, thinker, inventor, conversationalist, and bon vivant, Julian Nott, passed away peacefully on March 26 after suffering multiple injuries from an extraordinary and unforeseeable accident following a successful balloon flight and landing in Warner Springs, California.

Every second or third Saturday morning, depending upon his schedule, we would meet for breakfast at Tre Lune on Coast Village, where we’d discuss subjects from the existence of multiple universes to the presidency of Donald Trump and everything in between. I thought of him as my mentor; he knew so much about so much, though I may have had the edge in politics. I looked forward to our conversations and our breakfasts and have trouble believing that I’ll never see him again.

A Little Background

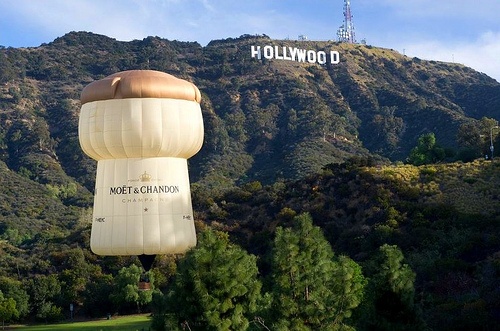

The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum has described Julian as “a central figure in the expansion of ballooning as an organizer, pilot, and most of all as arguably the leading figure to apply modern science to manned balloon design.” The craft he designed and built for his record-breaking early 55,000-ft ascent is on permanent display at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Over the past decade, Julian had tested and designed a type of balloon for NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena that was meant to fly in the frozen nitrogen atmosphere of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. To that end, he and two UCSB students set a world-record low nitrogen temperature during an experimental build-out simulation of Titan’s atmosphere in an unused building just off campus. Julian also headed up the StratEx team that powered Google Senior Vice President Alan Eustace to a world-record 41,422 meters (135,899 feet) above the surface of the Earth in a balloon of Julian’s design and exact specifications, before landing back safely to the ground.

Nott had been working on his patent-pending cryogenic helium experimental balloon with a pressured passenger cabin. The AN balloon used compressed helium in twin storage tanks instead of hot air, which allowed it to stay aloft longer and fly at a much higher altitude.

Katie Griggs, Western Region director for the Balloon Federation of America, said everyone in the industry was also closely watching Nott’s AN cryogenic balloon project. “It will probably be one of the most incredible inventions in ballooning,” she said.

Our Conversation

What follows is my conversation with Anne Luther at the Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf on Coast Village Road, just two days after Julian’s death.

“It was always easier to say ‘my wife,’ rather than ‘my partner,’” Anne explains when I tell her I had no idea they weren’t actually married. “I was a little concerned [if that would cause a problem] at the hospital,” Anne says, but adds that she “had full power of attorney for everything.” She was told that trumped even a marriage certificate. “I’ve been married a number of times,” she says with a laugh, “and this relationship was much better than any marriage I had. He was the love of my life and I of his.”

Julian had been working on this particular project for the past three years and he was nervous about it because every aspect of it was new. The cabin, the parachutes, the helmet, the lighting, the breathing apparatus, communications, everything that went into this aircraft he designed from the ground up.

“It’s experimental,” Anne says. “Nobody’s ever done it like this before. I think he had twenty-six patents on it. His oxygen system was of his own design. He had sixteen serious scientific experiments on board. Everything had to be tested: the construction of the cabin, the way the cabin was shaped, the way the balloon was inflated, the way it was attached to the cabin, the insulation in the cabin, the pillow he was to sleep on…”

On board were scientific experiments for Google, UCSB, Caltech, the University of Florida, and others. “Julian wasn’t just a balloonist,” Anne insists. “He was a scientist, an engineer; yes, his plan was also to go around the world (in the Southern Hemisphere) and break that record for speed too. But, it was never about the records; it was about the science.”

What Happened

He was going for two or three weeks to do the test flight. He left and he and Anne stayed in touch but the weather hadn’t been right. He took off from Tustin, California, in one of the few remaining vintage airship hangars, in which they inflated the balloon. While there, Julian had agreed to become the spokesperson for a campaign to preserve the enormous hangar, one of only four that still exist in the U.S. “He said we’re launching tomorrow; the weather looks good,” Anne recalls.

That was Saturday night, March 23. His chief of staff said they’d email her when they landed, which they did.

“About five hours into the flight, it didn’t feel right,” Anne recounts, “but he called to tell me he had just landed. I asked if he was sure he was okay. ‘I don’t have a scratch on me; I’m fine,’ he said, but admitted he didn’t get everything he’d hoped for. Then he said he had to gather up the balloon, as they always do, and said, ‘I’ll call you later.'”

About two hours later, Anne says she gets a call from a mutual friend at the site who gave her the bad news. The cabin had come loose. Julian and his co-pilot had gone into the cabin to get stuff. The chase team was already there. They’d hiked up the mountain in the rugged terrain and the plan was that Julian would hike down (he was a hiker); they were preparing the cabin to be airlifted out by helicopter.

Everything seemed normal, but as they both went into the cabin it started to rock. One of the team members shouted, “Look out; the cabin is moving,” but as soon as he said that, it tumbled. The Plexiglas dome that allowed Julian to stand underneath and look around was open and when it tumbled, Julian was thrown out; the co-pilot remained inside the padded interior and survived, though with broken bones.

“I don’t know how far it fell,” Anne says, “but it was significant. He was thrown out with no helmet, no flight suit, no boots.”

Julian hit his head on the way down and suffered a broken back and neck and had other injuries. First responders got there within thirty minutes and he was airlifted to the Palomar Trauma and Medical Center in Escondido. Michael and Mary Dan Eades, friends of theirs in Montecito, are both doctors and they stayed in contact with the trauma center and kept Anne informed. He was in surgery for about ten hours after which the doctors told Anne that Julian’s body would pull through but they weren’t sure about his brain.

“For all the time we spent together,” Anne states, “we’d always talk about what to do if he had a brain injury. We never spoke about cancer, heart attack, or anything else, but boy we talked about brain injury. He was adamant about his brain and keeping it protected.”

So, she understood that it was probably the end when she was told about the brain traumas.

“He lasted about thirty-eight hours; then his heart stopped. It was peaceful and I was so glad I was there, holding his hand at five o’clock in the afternoon as if he was having a nap.”

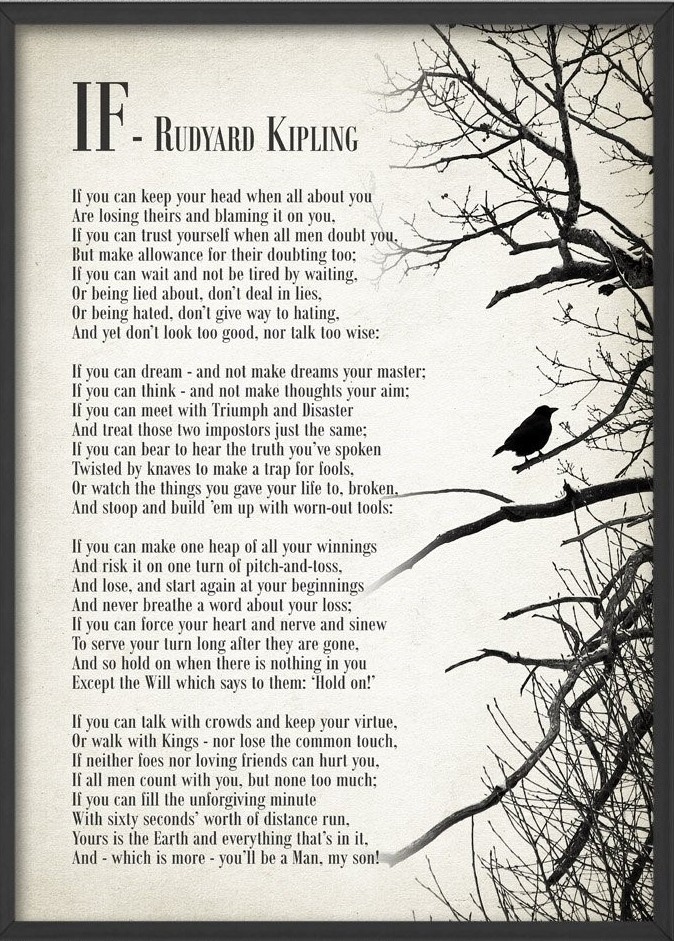

Julian was a fan of Hunter S. Thompson’s, and Anne reads me a favorite quote: “Life’s journey is not to arrive at the grave safely, but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke and loudly proclaim, ‘What a ride!'”

“And, that’s how he died,” Anne says softly. “Rather than in a crash on 101, or something else, he was in a nature preserve, where he loved to be. If there’s any comfort that I can have from this is that he just finished a very successful flight and a very successful landing for a project that he’d been working on for three years and that he loved. It didn’t take his life. It was something else.

“He landed safely.”

She has been comforted by hearing from so many people he’d inspired, many prominent in the world of aviation. “He was a good soul,” she says, “and he’s in a safe place and a happy place. I know that.”

Julian wanted to be buried with his father in Surrey, England, where Anne and he had gone to visit his father’s grave many times, near a historic chapel and historic cemetery with a view.

“If there’s a heaven on Earth, this is it,” she says.

Julian will be on his way in a week or so. He’ll be interred in the Watts Chapel with his immediate family. He’ll be dressed in his favorite clothes: his 501 jeans, no socks, blue shirt, and his new flight jacket for this project, and an American flag, because he was so proud to be an American. There are aviator wings on the casket.

“He and I had a symbol of our closeness,” Anne relates, “we always held hands before we went to sleep. About twenty-five years ago, he was going through a rough period and I gave him a large silver charm in the shape of a hand. I said ‘Why don’t you just put this in your pocket and pretend this is me when you’re on this trip (he was going to Asia).’ It meant so much to him and he kept it with him always. Often when he was in a faraway place and he was lonely, he’d send me a picture of him and the hand. I was together enough to remember to take it out of his pocket, so that will also be in his casket.”

Anne promises she will do something here in Santa Barbara to celebrate Julian’s life, probably in June, in association with what would have been his seventy-fifth birthday (the 22nd). But, it’ll depend upon when the airport can accommodate them. The Society of Experimental Test Pilots will do something around the same time, as will the Aviation Trade Association in Oxford, the Smithsonian has plans to remember him too.

Anne jokes that circulation of the Montecito Journal will go down by one, because Julian would never agree to read her copy.

“I would pick up the paper and would have to pick up two copies,” she recounts, “one for me and one for him and his always had to be pristine. When he traveled, I always had to run around and have a copy for him when he came home. I’d put it on his desk.”

Last year, he trained with the U.S. Navy Seals in San Diego, where they parachuted into a very rough and cold ocean, so he’d know if he was capable of jumping out of a balloon that may have been on fire into the ocean. They had survival rafts, custom made and covered with a hood and he practiced getting in and out of it. “It looked to me like a shark burrito.” He could have landed and had been devoured by some creature, or he could have landed in hostile territory and taken hostage or shot.

“But he landed safely.”

•••

Julian Nott’s beloved Anne Luther, his brother Robert Nott, and nieces Elizabeth Salmon and Katherine Nott survive him. Interment will be in the Nott Family Plot in England. In lieu of flowers, Julian’s wishes were for donations to his favorite charity, SEE International, www.seeintl.org.