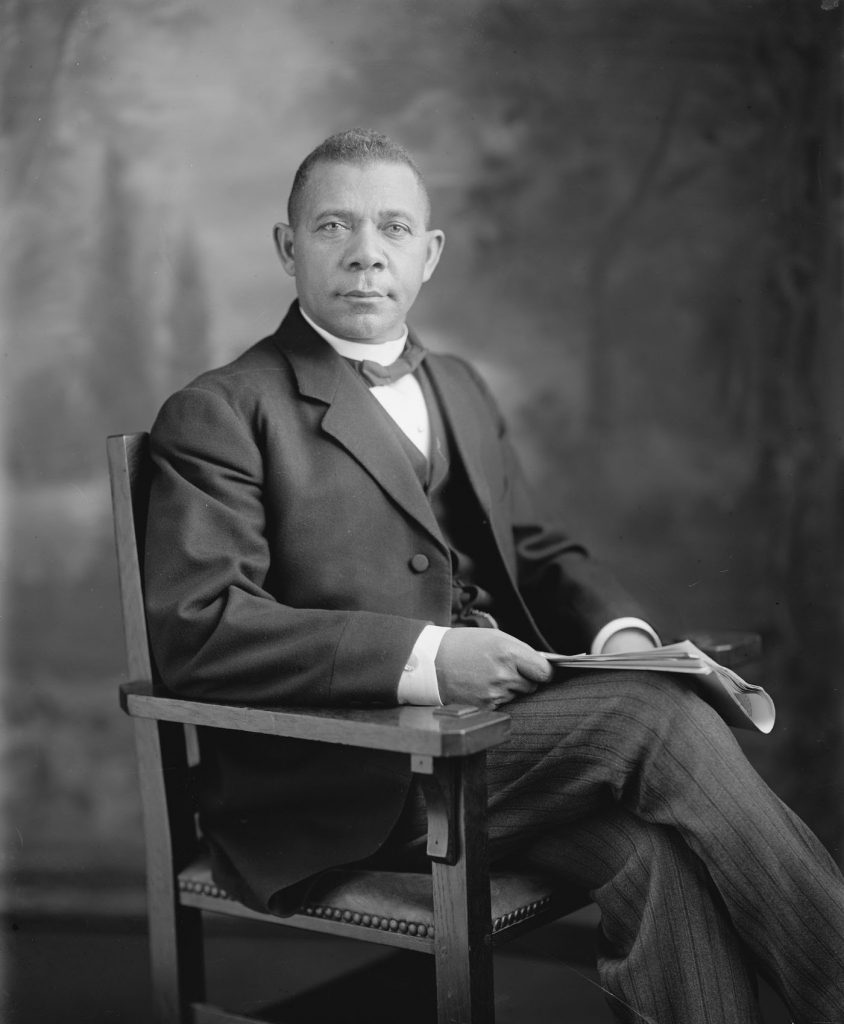

When Booker T. Washington Came to Santa Barbara

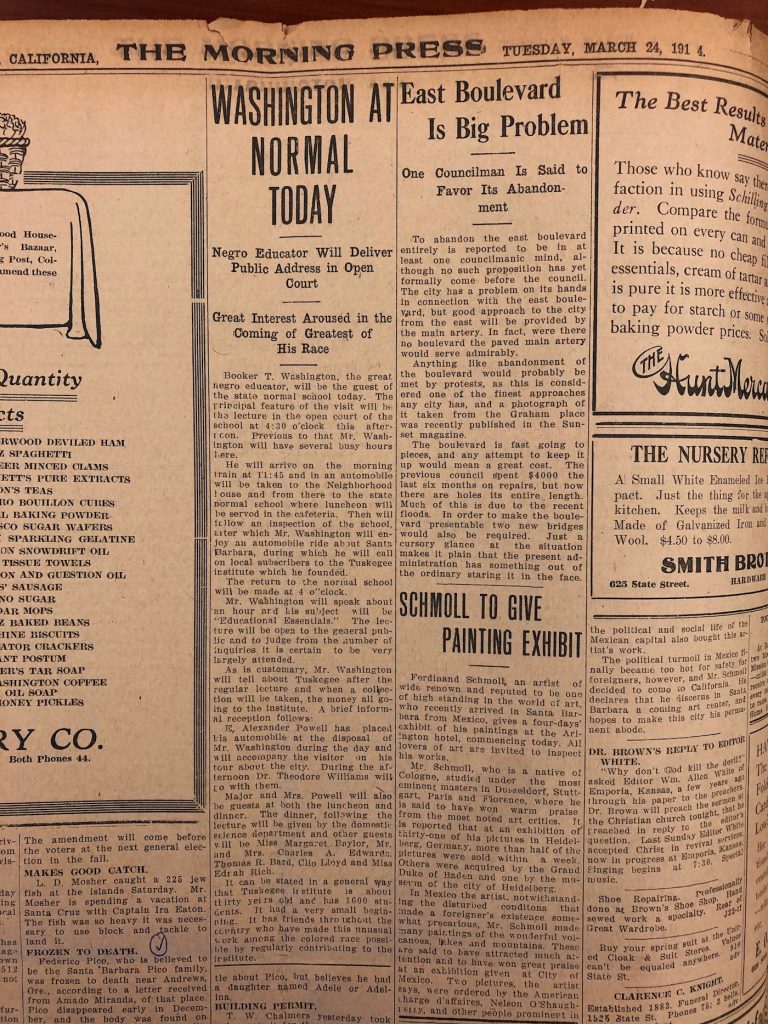

In March 1914, Santa Barbarans were filled with anticipation because the famous leader of Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington, was coming to town to speak at the State Normal School of Manual Arts and Home Economics. Articles in the Morning Press told the story of his rise from the privations of slavery to becoming one of the most important educators in the United States.

After their emancipation, his mother had moved the family from Virginia to West Virginia where he taught himself to read and went to work in the coal mines. Eventually hearing about Hampton School, a school for former slaves, he was determined to enroll and work to pay for his tuition.

Washington excelled, and at age 25 he was recommended for the position of principal at a new school just opening in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1881. The school, which held its first classes in a rundown shanty and church, became enormously successful under his leadership. By 1914 the school had 1,600 students from 36 states and 197 instructors. It could boast 3,000 acres of land and 107 buildings.

On March 24, 1914, Booker T. Washington came to Santa Barbara on a train that arrived one half hour late. Indicating the esteem in which he was held, the Southern Pacific Railroad had held the train when a mix-up caused him to be tardy. Major E. Alexander Powell met Washington at the station and gave him a tour of the town, showing him those great social and educational institutions of Neighborhood House, the newly opened Recreation Center, and the new YMCA building. Washington was impressed.

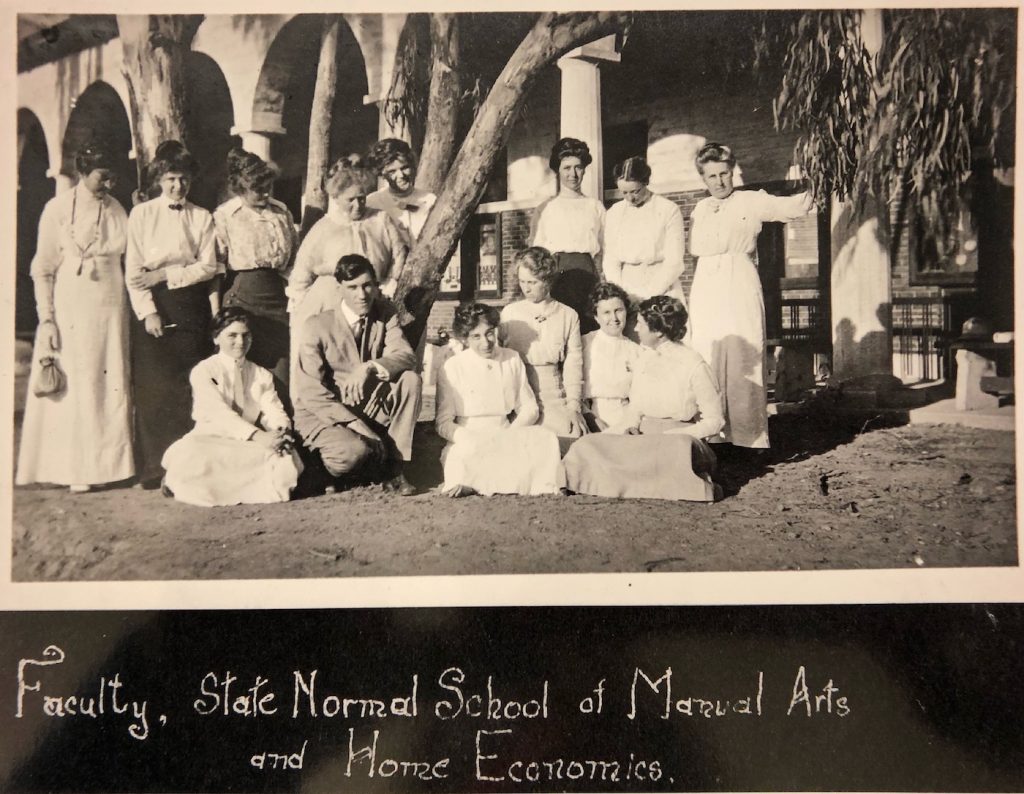

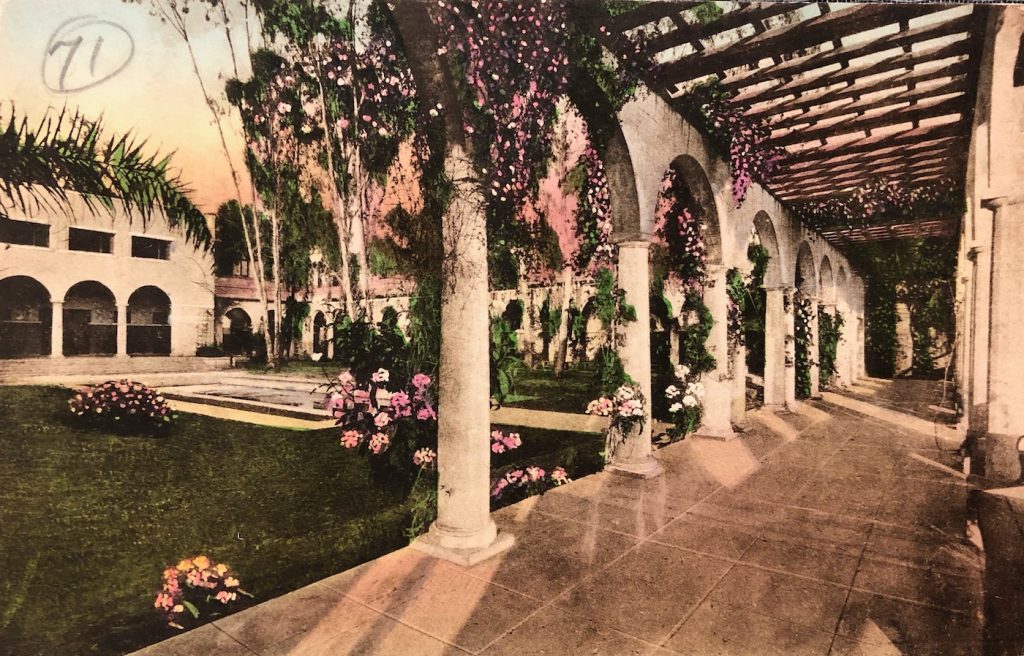

When he arrived at the State Normal School’s new campus on the Riviera, he was met by principal Ednah Rich, who had invited him to come to Santa Barbara when she attended a conference the previous year at Tuskegee. (Ednah Rich had been involved with education in Santa Barbara since the 1890s when she joined the staff of the Sloyd School founded by Anna Blake in 1891.)

Washington spent the day touring the school and its various departments, had lunch in the cafeteria, and a special dinner given by the domestic science department. Among the guests was Miss Margaret Baylor of Neighborhood House and Recreation Center, the revered social worker whose heart, vision, and work so benefited Santa Barbarans. A link to her story may be found at www.thegivinglist.com.

Theodore Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to a dinner meeting at the White House. Many in the nation were shocked, and the repercussions severe. In a National Public Radio interview with Neal Conan in 2012, Deborah Davis, author of Guest of Honor: Booker T. Washington, Theodore Roosevelt, and the White House, talks about those repercussions.

“There was hell to pay,” she said. “First weeks, then months, then years, then decades. This story did not go away. And, you know, an assassin was hired to go to Tuskegee to kill Booker T. Washington. He was pursued wherever he went. Theodore Roosevelt was criticized in ways that presidents were not criticized. There were vulgar cartoons of Mrs. Roosevelt that had never been done before. This was all new territory.”

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt went on the campaign trail in California and visited Santa Barbara. Security for the event was prodigious. After he alit from the special train in Montecito, a cortege of carriages carried him first to Plaza del Mar for speeches and then along State Street as it headed toward the Mission. At some point along the route, a young African American girl named Ruth Cordero was allowed to approach the carriage and present the President with a bouquet of flowers. Roosevelt would remain an advocate for the betterment of African Americans and a supporter of Tuskegee throughout his presidency.

The 1914 Speech

The day of the speech, the streetcar was kept busy, ferrying people to the station on the hill near the Mission. As 1,500 Santa Barbarans (a group that included 150 school children and their teachers) settled into the chairs set up in the open court of the Normal School on the Riviera, Ednah Rich introduced Dr. Washington, who was greeted with warm applause. “The audience clearly appreciated,” reported the Morning Press, “the opportunity to see face to face one of the world’s great men.”

“I do not know when I have experienced such a delightful surprise as this unique institution,” said Washington in opening his speech. “I value this work here most highly because of its rich and beautiful simplicity.”

In talking about developing the educational program at Tuskegee, Washington said, “We are striving to adapt our education to the exact needs of our people. Before a single lesson was taught, I lived, in all its details, the life of black farmers around Tuskegee. I soon discovered an ambition among my people to secure book education and a feeling that it was a disgrace to work with one’s hands when one could read and write and cipher. So we began to teach books, but meanwhile school-buildings were built by our own students and we taught farming – not this thing you call agriculture – and cooking – not this thing you call household art.

“My people came by the score and said they had been worked in slavery long enough, that they sought to be freed from work by education. I replied that there is a vast difference between being worked and working; that we are trying to teach the future leaders of our people how to work. In a state of freedom, every man must learn to work.”

As far as the method of instruction, Washington said, “I could never see any sense in studying about a thing, when you can study the thing itself. Now we study at Tuskegee problems taken from the farm, the harness shop, the dairy, the shop – vital problems.”

Once this idea took hold, the commencement ceremonies changed from esoteric lofty speeches and sentiments to more practical topics. As an example of the “reformed” commencement, Washington stated, “… a girl prepared a model farmer’s dinner, illustrating and carrying out every process and telling at every step she was using some course in mathematics or dietetics… I wish you could have heard a recent graduation oration on turnips; not on the history or psychology of turnips, but on how he grew turnips, and how he used chemistry in enriching the soil, …”

On the subject of race, Washington told a wonderful tale. “Sometime ago,” he said, “an old colored man was travelling with me and he nearly missed his train. He found a hackman and asked him to drive him to the station. The hackman had never had the experience of a colored passenger and urged him to find a black driver. ‘I ain’t got no time to hunt another diver, Boss. You jus’ climb in here and let me sit up tha’ and drive yah.’ So the colored man caught his train and the white man got his fare.”

“Let us forget the tantalizing and perplexing details of race-adjustment,” concluded Washington, “and, with hearts fixed on the service of both, press forward to the greater progress of both races.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.