The Natural

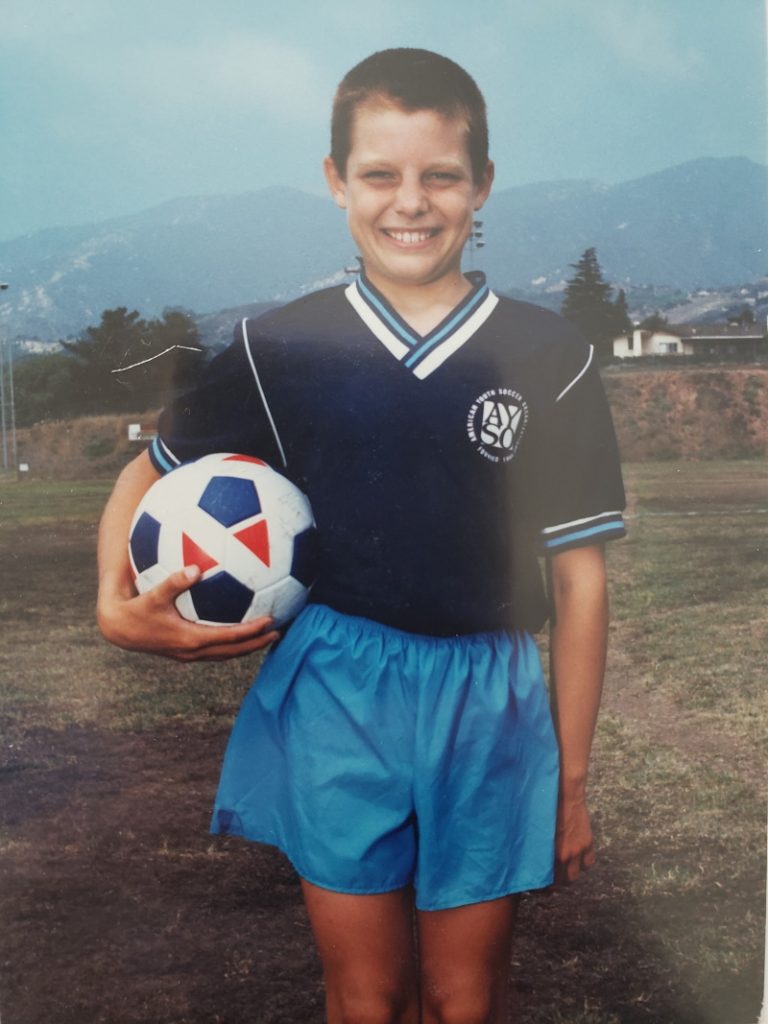

I was once in a race against Chris Tamas. To this day, I doubt that Chris is even aware of this. For him to have known we were in the same race, he would have had to be looking way back to find me, struggling amongst the other laggards who didn’t belong on that track. It was the mile and we were both sixth-graders at Montecito Union competing against other elementary school kids in a citywide track and field meet. And what I recall most vividly about that race, apart from my glaring mediocrity, was how Chris dominated it from start to finish; the way he galloped to greatness with seeming effortlessness and how I labored to the finish line with tiny, mincing strides. Of course in those days, Chris won just about everything that could be played on a field, a track, or a court, and he was probably great on skis and at snooker for all I knew. In the classroom we were all equal sixth-graders, but the minute we stepped outside, it was Chris’s world and we were all just living in it. I was 10, and thanks to Chris Tamas I knew exactly what I wouldn’t grow up to become.

So I was hardly surprised when I learned years later that Chris had been a sensational volleyball player and that he had played on the U.S. national team and that he had become one of America’s best college volleyball coaches. If anything, these facts conspired to lend meaning to my aborted experiment with sports. But thinking again about that race, though, it’s not hard to imagine why Chris wasn’t looking back. He seems to have spent his entire life looking forward.

The Third Set

Two years ago, in the third set of the NCAA women’s volleyball semifinal, the Fighting Illini of Illinois had the defending national champions, the Nebraska Cornhuskers, right where they wanted them – in a 2-0 hole and on the brink of elimination. Ashlyn Fleming, a 6’4” junior from San Jose, was holding the ball behind the service line. Just a few months before, Fleming had transferred to Illinois from Chris’s alma mater, the University of the Pacific, where she had been a standout middle blocker. Now her team was up one point and needed only two more to reach the final.

For Illinois, just being there was a huge achievement. It was only Chris’s second season as the head coach of any team, let alone a major program. In his first year, Illinois had shocked the volleyball world by taking an unranked team into Seattle to knock off No. 8 Washington and advance to the Sweet Sixteen. In 2018, Chris led the school to a record of 32-3 and to just its fourth ever Final Four appearance. The team hadn’t lost a match in more than a month and all of a sudden it had pushed the defending champs to the edge of a cliff.

On some level, Chris knew the situation well enough to know that Nebraska would roar back. He knew this in no small part because before coming to Champaign, he had been Nebraska’s assistant coach. He knew his team was facing the same coach, John Cook, and essentially the same group of players with whom Chris had won a national championship and reached another Final Four. “I thought we matched up great against Nebraska,” Chris said.” I know the girls were excited to be there and we played some really good volleyball. But I know Nebraska’s very talented, I coached most of those players for two years. The seniors on that team had been in those scenarios a lot.”

As Fleming prepared to serve, she sucked in a gulp of air and composed herself before launching the ball to the other side. Nebraska libero Kenzie Maloney picked up the serve with poise, setting up an easy finish for middle blocker Callie Schwarzenbach.

“Schwarzenbach able to come through with the kill, tied at 23-23,” roared the announcer.

Nebraska didn’t waste any time taking advantage of the swing in momentum. Seconds later, Mikaela Foecke, team captain and two-time All-American, rose into the air, leaned into a perfectly placed lob and punished the ball into the hardwood floor. 24-23 Nebraska. On the next point, Illinois mishandled the bump and sent an easily defendable ball toward Foecke, who spiked another winner and the set was over.

“Nebraska stays alive by taking the third,” the announcer growled.

The Talent

When Chris was five years old, the Tamas family relocated to Montecito from Irvine and built a Spanish-style home on a one-acre lot on Bolero Drive. By then Chris was already revealing his athletic potential. He had taught himself how to ride a bicycle and he could shoot baskets into a 10-foot hoop when he was three. “When he was two or three, his hand-eye coordination was already evident,” said his father George. “He was able to hit a fastball right from that age.”

Chris’s parents, both avid athletes, nurtured their son’s sporting pursuits by putting a tennis court and a basketball hoop in the backyard. He ran the Montecito Union School track on weekends. “I remember just liking sports very early on and just whatever I could get my hands on, I enjoyed playing,” Chris said. He more or less fell into volleyball in seventh grade, when he and a buddy agreed to join the team at Laguna Blanca to fill two remaining roster positions. He was a lot shorter then, but he immediately took to being a setter, a position that requires constant communication and rapid decision-making. By the time he was 14, he had sworn off individual sports. He had excelled as a tennis player, “but I was hard on myself,” he said, while swimming and track had become “a little boring to me.”

Chris continued to play basketball and soccer, but he threw himself headfirst into volleyball. Between his freshman and sophomore year of high school, he grew another six inches, as if he had willed his body to equal the height of his talent and passion for the sport. By the time Jason Donnelly joined Laguna Blanca as its volleyball coach in 1995, the Chris he met was less a tall and skinny teenager than a towering man of 6’5” with unnatural hands and all those innate aptitudes you look for in a leader. “He was just a natural and he just had to learn how to make that work on the court and how to pull that from his teammates,” said Donnelly, who is now Laguna’s athletic director. “Chris is one of those players who makes people around him better just by being himself.”

As a teenager, Chris was as shrewd as he was talented. Full-ride college scholarships were rare for men’s volleyball players and even though he received multiple offers from prominent programs like UCLA or UCSD, Chris chose a smaller school with a lesser pedigree, the University of the Pacific. “His decision making was very clear, he knew what he was looking for and wanted to go U of P instead of UCLA, which was unheard of for a guy with that kind of talent,” said Donnelly, who also played volleyball at the Pacific. “It was just another example of him being him and staying true to who he was and what he wanted to do.”

Sacred Bonds

There is a convincing argument to be made that of all the team sports, volleyball is the most team oriented. Baseball, for example, is simply an individual sport disguised as a team one, wherein the selfish interests of the player are almost always aligned with those of his teammates. If a pitcher throws a strikeout, he has aided his team’s cause just as much as his own. In basketball, a player is constantly conflicted between what is possibly best for him (taking the shot) and what is best for the team (making the pass). Even in football, a sport whose team dynamics are most compared to volleyball, a quarterback can ignore throwing to available receivers down the field and elect to run it himself. By contrast, volleyball rarely rewards players for their individual exploits. It is a game that insists on its players perpetually working as a group in a clockwork of carefully calibrated sequences. An all-important dig makes that first essential bump (a pass) possible, a bump precipitates a set, and an effective set enables a perfect spike. “You cannot play the game one-on-one,” said Chris’s wife, Jen, a highly accomplished volleyball player in her own right. “You rely on everyone else’s touch to make a play and you’re constantly bettering the ball for your teammates with each perfect touch. There are so many times that require all of us running through fire for each other.”

Indeed, every team sport has a way of forging a sacred bond between even the least devoted of its participants. What makes volleyball peculiar, though, based on my statistically insignificant sample of players, is how frequently those attachments become matrimonial. John Cook’s wife, Wendy, for example, was a two-time All-American setter at San Diego State. Russ Rose, the longtime head coach of the women’s volleyball team at Penn State, married Lori Barberich, who was a former three-time All-American, also at Penn State. Meanwhile, Hugh McCutcheon, the coach at the University of Minnesota, is married to the former Elisabeth Bachman, a standout at UCLA who played on the U.S. national team at the 2004 Olympics in Athens. And that’s just coaches in the Big Ten conference. My superficial research on the subject has revealed that marriages abound in the cloistered, close-knit universe that is competitive volleyball.

Then there’s Chris and Jen. They met while he was a freshman at the Pacific, where he was already a starter and team captain. It was the fall of 1999 and Jen was visiting schools as a high school senior attending an all-girls Catholic school in San Jose. She first noticed Chris in a practice at the Pacific, describing the encounter as “one of those moments where it was as if nobody else existed in the gym except for him. I was watching him from the bleachers and I thought, ‘Holy smokes, who is this guy?’” Chris and Jen dated briefly her freshman year but Chris broke it off. “Long story short, she wanted to get serious, and I didn’t,” Chris recalled, with a laugh.

Friendship and volleyball kept them close throughout their time at the Pacific, where they were both first-team All-Americans in 2003. “I set him up with my girlfriends and he had me proofread his girlfriends’ love letters to him,” said Jen. “He would say things to me like, ‘Jen, I think this is a red flag, do you concur?’ We were really close friends.”

When they were both playing for the U.S. national volleyball team, they trained together in Colorado Springs. And a few years later, while she was playing for the national team in Japan and he was playing professionally in Cyprus, it was volleyball again that reconnected them. They began dating again months before the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and Jen was selected to be on the team just weeks before the start of the games. “That summer I was on the phone with her every day until the early hours of the morning trying to help her with her nerves and calm her down,” said Chris. “She obviously did all the work.” Shortly after Jen came home with a silver medal from Beijing, she and Chris got engaged and they married a year later in Paso Robles.

When I pointed out to Jen the number of married couples in the volleyball world, she wasn’t surprised. For starters, she told me she and Bachman had been roommates for five years while Bachman was dating McCutcheon, whereupon I concluded that volleyball wasn’t merely a close community but rather some benevolent cult. Jen lent further proof to my working theory by bringing up other volleyball marriages, including that of Texas volleyball coach Jerritt Elliott and Sarah Silvernail, who is regarded as the greatest player in the history of Washington State University. As to why so many volleyball players tie the knot with fellow volleyball players, Jen helped me make sense of this idiosyncrasy. She offered that it had something to do, in part, with volleyball’s way of drawing out essential virtues from its players, like devotion and self-sacrifice. “I think we gravitate towards people that are like that, just selfless people,” she said. “If you get a volleyball couple together with those values, we stay together for life.”

The Fourth Set

Illinois had jumped out to an immediate lead by essentially throwing Nebraska off guard. It cruised through the first two sets with four aces and no errors on its serves, an impressive stat given the team’s trademark aggressive serving. “We had a really good system, we used a really fast attack out of the back row, which you only really see in the men’s game,” said Chris. “It was difficult to stop if you’d never seen it.” By the fourth set, though, the team began committing miscues that kept the score neck and neck. But over time Nebraska’s experience and its defensive adjustments began wearing down its opponent. The defending champs built a commanding lead and took the fourth set with relative ease.

In any given year, the Big 10 conference is arguably America’s toughest. In 2018, it was unquestionably the most dominant, sending seven teams into the NCAA tournament, five of them ranked in the top 10. Illinois has historically been a top 30 program but has struggled to reach elite status. That rarefied air is reserved for perennial top fives like Stanford and Nebraska. And far as coaches go, John Cook of Nebraska is the gold standard. With four national championships, he is the volleyball equivalent of Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski.

Chris swears it was all an accident, and I believe him, but his whole life has been a perfect blueprint for a head coaching job. For starters, as a professional player he was willing to cross to the farthest reaches of the planet for experience, whether it was Portugal or Spain or Finland or Cyprus or Turkey. In addition to Donnelly as a coach at Laguna, he also had Todd Rogers, the same one who won five Association of Volleyball Players championships. He played under the great Joe Wortmann at Pacific and served as an assistant at UC Riverside under Ron Larsen, a coach of the U.S. women’s national team, at Minnesota under McCutcheon, also a coach of the U.S. women’s national team, and then a two-year stint at Cal Poly under his former assistant at Pacific, Sam Crosson. In every coaching job Chris has held, Jen has sat a few seats away from him on the bench, where she serves as a volunteer coach and the team’s surrogate mother.

By the time Illinois came calling, at just 36 he was as close as it gets to a sure thing. Chris’s volleyball trajectory is comparable to a genius who spent 30 years as a computer programmer and worked with Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Larry Page before taking over his own tech company.

“In the coaching world, we are all products of our environments to a certain degree,” said Crosson, who is now head coach of the women’s team at UC Berkeley. “The thing that often gets overlooked is how much time Chris has put into his craft. The things that he’s doing at Illinois are absolutely not a surprise. He’s very good at understanding the environment and he just has this relentless pursuit for maximizing the people around him in a very united way.”

(And while we’re keeping score, Crosson is married to, yes, a former volleyball player, the former Courtney Miller, who played at the Pacific.)

The Fifth Set

Following the 2006 season and after 34 international appearances, Chris was released from the U.S. national team. He was 25 and it was the first time in his entire life he’d been cut from any team in any sport. When I pointed this out, the observation didn’t seem to sting him. The people who know Chris – his wife, his parents, his coaches – all vouched for his ability to stay focused on what’s next and that he conveys this mindset to everyone around him. He treats defeat like any other mundane letdown that life will one day throw at you. Sometimes it rains, sometimes you lose, one day a girl will break your heart and eventually you may not make the team. “Sure it’s tough when it’s something that you know and it’s something that you spent your whole life on,” Chris said. “But I also have perspective of it too and even at the time, that everyone’s really good and I just didn’t shine when I needed to. That’s just the way it goes.”

Perspective is something Chris talks about a lot these days. His team would be playing a new season now but with matches postponed until the spring of 2021, his players must grapple with a hard reality: that this year will be the first in their young lives without competitive play. It’s a relatively young team that replaced the loss of five starters. Chris has utilized the off time with team-building activities, including frequent discussions over Zoom.

“We kind of made the decision to not focus so much on the volleyball side of it because they couldn’t play,” Chris said. “You could take a ball and pass off a wall but it’s not the same as playing six on six with a ball that’s being hit at 70 miles per hour towards you. I didn’t see it as the time to say, OK we’re going to get better as players during this pandemic other than we’re going to get better as a team and improving the players as people.”

It was then I realized that Chris approaches volleyball in the same way he and Jen have helped me to see the sport – something which is as much a family bonding experiment to be nurtured as a game which can be mastered through repetition. To keep the disruptions caused by COVID-19 in perspective, Chris says he thinks about what his father and grandparents had to endure when they escaped Lithuania at the height of World War II. Pinched between Nazi forces and the advancing Russian army, the Tamasevicius family fled its home in Kaunas and spent years in a displaced persons camp. They landed at Ellis Island in 1949, abbreviated the name to Tamas and wound up in Amarillo, Texas.

A year ago, the bonding experiment that is the Tamas family was further nurtured: Chris’s parents, George and Mardee, left California and moved to Champaign to help Chris and Jen raise their three kids – Jimmy, Josephine, and Carly. True teamwork, on a court or otherwise, requires proximity.

As the fifth set got underway, the riskiness of Illinois’ aggressive serving was rearing its ugly head. It missed three consecutive serves and committed more unforced errors, preventing the team from closing out the match. But incredible play at the net gave Illinois, improbably, an early edge. Leading the way were Jordyn Poulter and Jacqueline Quade, two outstanding players who among so many other things came to incarnate the excitement that Chris brought to Illinois volleyball. Quade was a dominant force in that semifinal, leading all players in kills. And she punctuated that fact with her 28th kill late in the set to tie the match at 11.

Nebraska took the next point and on the following exchange, Foecke spiked a ball that was initially called out of bounds. The ruling tied the score, but a video review overturned the call. 13-11 Nebraska. And suddenly the atmosphere in the arena in Minneapolis became something entirely different. Pro-Nebraska chants of “Go Big Red” filled the air and what had one minute ago been an even contest on a neutral court felt like an away game. Illinois botched a return (14-11) and moments later Foecke spiked the game winner and the comeback was complete.

What happened next was something both touching and yet utterly confounding. Illinois had been two measly points away from reaching the final and it had just given away a nearly insurmountable lead to the defending national champions. It’s the kind of devastating, season-ending defeat that reduces even seasoned pros to fits of consternation. Grown men have flung their weary bodies onto grass fields and hardwood floors and wept tears of agony in contests of lesser significance. But the women of the Fighting Illini entertained no such nonsense. They simply gathered in a huddle and pumped each other up, as if to get ready for the next point, which in this instance would have to wait until the following year.