Then and Now

Judging by the unsolicited emails I receive, there seems to be quite an industry based on putting people in contact with others they knew years ago but have completely lost touch with – particularly people they may have known at school.

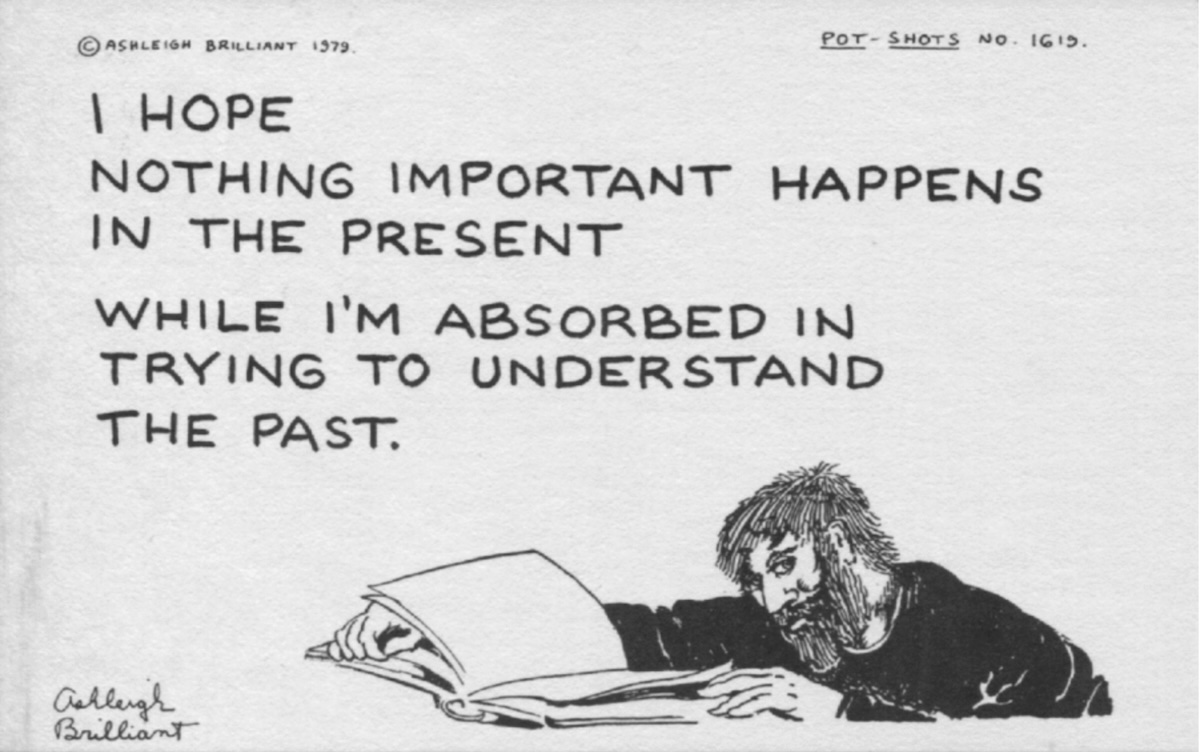

The sentimental interest in one’s own irrecoverable past has a very pretty name: NOSTALGIA. With me, it has two faces. I have kept a diary since I was ten years old. I did all the writing by hand in bound volumes, until home computers became available. Those volumes are all in a file cabinet in my room – but I rarely look at any of them. They are not indexed in any way – so, even if I wanted to check some fact or memory, it would be very difficult to do, especially if I am vague about the date.

But I have to admit that it can be very depressing to see “then and now” sets of photographs, particularly of people I once knew. That would, no doubt, be true of oneself – which explains why, since some years ago, I have avoided looking in mirrors, let alone being photographed.

Of course, up to a certain point, the changes we go through, from birth onwards, are not usually such as to render us less photogenic. Even when (as I suppose, in our culture, is truer of women than men) we become physically less attractive to the opposite sex than we might wish to be, our changes in appearance do not usually make us “ugly” or “repulsive.”

But, with the onset of what is generally termed “old age,” any set of “then and now” pictures is highly unlikely to favor the “now” over the “then.”

All this we owe to an invention – or a series of inventions – which began to appear only about two centuries ago, and which we call Photography.

The first photograph of any kind was taken by a Frenchman named Niépce in 1826. It was an otherwise not very interesting outdoor view, apparently captured from a balcony outside his studio.

After that, improvements came very fast, till it was possible, by 1903, for the Wright Brothers to have their own flying machine photographed in its first flight.

But looking back over all the ages before the advent of photography, how did people cope with the frustrating fact that it was very difficult to preserve an accurate image of anything? What we have in the way of pictures of the past are mostly the works of talented artists and painters. And what people most wanted to preserve were mostly “portraits” of themselves and each other. The costs involved made such pictures available only to the wealthy – which is why most of the images we can still see were of kings and queens and other members of the aristocracy. Fortunately there were in some countries, particularly Holland and Germany, some very fine painters who also took an interest in rendering landscapes, and ordinary people living their daily lives.

There was also something called a “camera obscura,” a dark room in which images of outside objects could be projected, and even traced, on a wall.

After photography came in, there were many artists who found it possible to make a living painting portraits – and there are even some still today.

Even back in so-called prehistoric times, as we know from the images left on the walls of caves, our distant ancestors drew pictures of what was most important to them, which was not usually depictions of themselves or each other, but the animals they hunted and depended upon, not only for food and clothing but for their tools and weapons.

The first sitting U.S. President to be photographed was James K. Polk, in 1845. Different processes were used, the main one having been developed by another Frenchman, named Daguerre. By the time of our Civil War, it was possible for some well-equipped photographers to follow armies into the field. Preeminent was Matthew Brady, who could not picture troops in action, but left us post-battle images of fields littered with corpses. But it was also Brady to whom we owe the fine pictures he took of President Lincoln.

Since then, the world has seen continuing improvements in the recording of color, sound, and motion – advances sufficient to make it theoretically possible to record every second of a person’s life – which will make future “thens” far more accessible to future “nows.”