Safe as Houses: Nancy McCradie’s 36-Year Homeless Saga

In idle moments we mull unimaginable experiences beyond our own. What’s it like to be launched into space? To be on a sinking ship in mountainous, hurricane-tossed seas? To be homeless?

“I was never embarrassed about being homeless. It was just a fact. I wasn’t psychologically traumatized by it all. Yes, it was very stressful at times because the community hated us and they set the police on us. But I made it through.”

Nancy McCradie is a onetime middle-class American who at a given moment found herself homeless and remained so for 36 years. Read that again. In the fullness of time – and following a contentious epoch during which McCradie and her cohort of homeless activist pals would agitate for change using various thorn in the establishment’s side strategies – the City of Santa Barbara would appoint McCradie to various boards and civic bodies, her eloquence and clarity of vision making her an increasingly useful spokesperson and liaison – and totem.

“I was their pet homeless person,” she says today, and there is no rancor in the remark. There is no rancor whatsoever in Nancy McCradie. Her years on the so-called “margins of society” have given her the 10,000 foot view the rest of us only fleetingly glimpse, and even then have no clue how to capably wield. If you can survive it, daily existence stripped to its urban foundation is a bracing and holistic teacher.

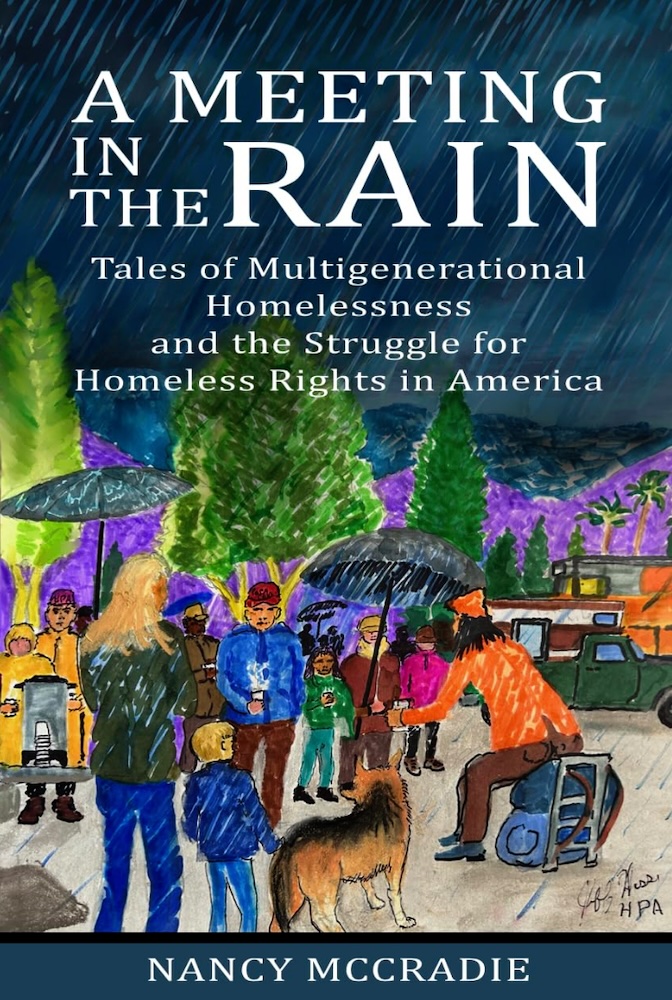

But what’s it like to be homeless? How does one inhabit those days and nights for years on end? McCradie’s new memoir A Meeting in the Rain (written with Bryan Snyder) answers the question with a lavish, blood-freezing, and ultimately stirring transparency.

“One of the reasons I wrote the book is because I actually liked my life – and I decided I wanted to put it on paper. When I got into a real house after 36 years living in my RV I felt cramped. I couldn’t go to look over the ocean for dinner, I couldn’t do this or I couldn’t do that. It took me a while. It took me about a year to adapt to living in a house.”

Hoff Heights

Nancy McCradie was born in Bristol, Connecticut to Herbert and Dorothy Fredlund on August 14, 1945. Mother Dorothy’s descent from William Brewster, chaplain aboard the Mayflower when that storied ship sailed from England in 1620, would affect the family’s fortunes not a whit.

The week prior to Nancy’s birth, the U.S. had dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a little-understood wartime calamity obliquely pinned to the blessings of Liberty that underwrite and infuse the recently-beleaguered U.S. Constitution. Nancy’s father served as chaplain’s assistant on a supply ship in the South Pacific during the war, returning home when Nancy was about ten weeks old. Work in Bristol was hard to find and eventually the young family decided to drive cross country and relocate to future tourist hive and Herbert’s hometown – a little-known beach burg called Santa Barbara.

Housing in the future American Riviera was scarce even then, and following mother Dorothy’s writing of a letter to the Santa Barbara News-Press lamenting the fact, the family was offered housing in a new and hastily-constructed development called Hoff Heights; a bric-a-brac complex of temporary homes built from a decommissioned military hospital and expressly offered to returned veterans. That acreage today is occupied by Santa Barbara’s municipal golf course off Las Positas Rd. Their family home at H67 Apartment #111 was less than ideal, but the Fredlunds were grateful.

Herbert undertook and completed a UCSB degree in Music and Secondary Education, the family obliged to quit town to follow the work. Their Odysseus-like, years-long walkabout in the name of Herbert’s gainful employment would take the Fredlunds to Calistoga, San Bernardino, and Barstow, and finally back to Santa Barbara, where an old chum named Henry Brubeck (Dave “Take Five” Brubeck’s brother) would connect Herbert with a job teaching music at La Cumbre Junior High.

Harbingers

Now a young woman with three academic units between herself and a Santa Barbara City College AA degree, McCradie would succumb to the familiar (and often fork-forging) temptation of a paycheck, comparative independence, and a life less woefully predictable. Opting not to return to class when the new term started, taking instead a job at the hand car wash next to the Jolly Tiger Restaurant on Canon Perdido St.(!), Nancy McCradie would unknowingly begin teasing the outer orbits.

This was 1966, the year the Beatles released their zeitgeist-buffeting Rubber Soul album. Was McCradie’s approaching epoch informed in part by the cage-free historical moment that would shortly uncork 1967’s Summer of Love? Who’s to say?

Transfer to a management role in the car wash’s Goleta location introduced McCradie to first inklings of a newish friend group and lifestyle. Her new tribe’s predilection for light adventurism and edge-tickling mischief would surreptitiously usher in the beginnings of her next long chapter – a comparatively riotous and spiritually nourishing sojourn in the leafy and starlit out-of-doors.

Fear and Love and the Jungle (A ‘Mayflower’ Descendent Sleeping Rough)

McCradie’s transition from housed to unhoused depended on a compounding of non-magical factors connected by two self-sabotaging and neatly braided threads – poor choices of companion, and a figuratively enlarged heart (not the condition cardiomegaly). She still carries a certain wayward gentleman’s name, he of the chapter she tactfully calls “A Marriage of Inconvenience.” McCradie and her son Sean’s final domicile of this period was the Pilot House Motel at Fairview and Hollister in Goleta.

When the Santa Barbara Airport closed the place down, the two moved into a green Ford 250 pickup with an El Dorado camper shell and found a welcoming community of variously strange and deeply supportive neighbors in the beachfront woodland bound by Milpas and Santa Barbara streets along Cabrillo Boulevard.

Fess Parker would soon enough raze these woods for the construction of his sprawling resort complex on the north side of Cabrillo. To Parker’s great credit, as the police were incessantly trying to clear The Jungle of its homeless community, Davy Crockett himself interceded and gave the beleaguered folks permission to stay for as long as it took to prepare for construction. Maybe Crockett’s having died at the Alamo fighting on behalf of the newish U.S. of A. gave the actor perspective on his fellow country persons. Pure speculation, of course.

By the by, Nancy McCradie finally found her anchor. Here is her unblinkered description of first seeing her future partner, flame-keeper, and lifelong emotional safe harbor. “In his arms he held a five-gallon bucket of ice cream that he must have scavenged from the dumpster near the Dreyer’s Ice Cream warehouse. For lack of a spoon, this lunatic was eating his dessert with a stalk of celery. Ice cream dripped down his face and the front of his overalls.” Protest Bob would later become a respected if sometimes bewildering presence at City Council meetings, and the radiant love of Nancy McCradie’s mildly star-crossed life. Yes, reader: spiritual competence and capacity for Love are not always evidenced by formalwear and mannered gestures – as we have seen. Still later would come gorgeous daughter (and present-day real estate magnate) Krystal Freedom, and a literal homeless march of fellowship from coast to coast to give Washington, D.C. what-for. In Santa Barbara, the restrooms by Marshall’s and the Safe Parking Program derive from McCradie’s activated, not-always-predictable, and screenplay-ready band of brothers.

“Protest” Bob Hansen would leave us, and his loving family, on March 12, 2024, passing away in the house he and Nancy finally shared.

It is safe to say we all feel disparate, and to one degree or another fear the homeless we see. The beautifully written and madly absorbing A Meeting in the Rain may not change your life or your biases. But it may well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.