Pictures Worth a Thousand Words

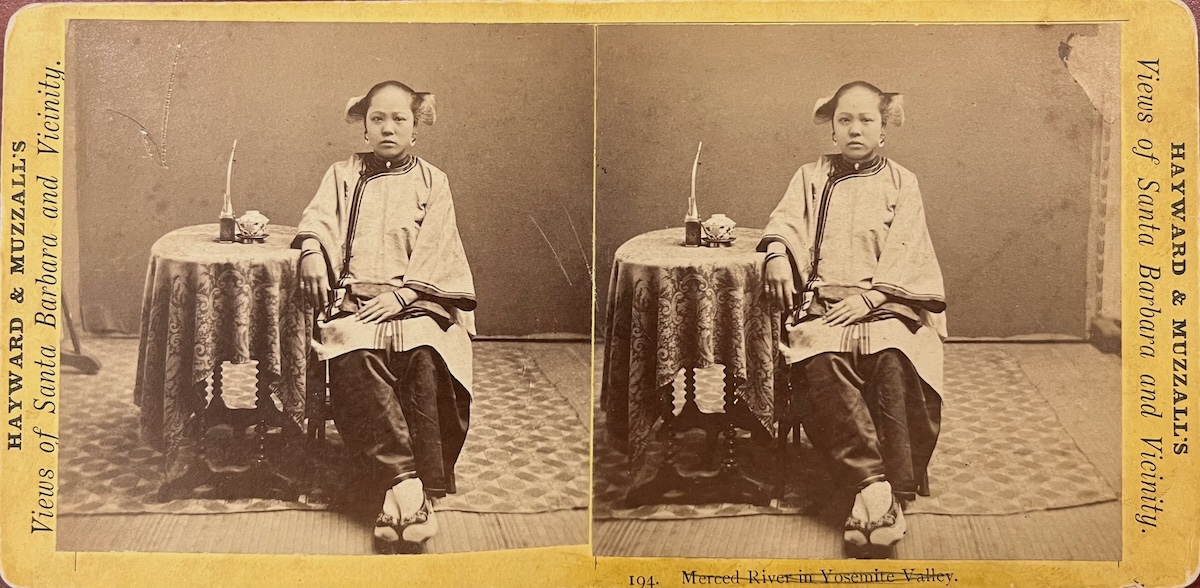

Santa Barbara has drawn photographers to its sunny climate, beautiful landscape, and charming architecture for over 150 years. Starting in the early 1870s with its first resident photographers, E. J. Hayward and Henry Muzzall, at least 11 photographers had set up shop by 1900. They documented the Mission and the adobes and the views from the mountains. They created stereopticons of the Chinese in Chinatown, the Big Grapevine in Montecito, and horseback excursions along West Beach. Today, these images provide a visual historical record of Santa Barbara’s unique past.

By the 1920s, a new group of photographers had replaced the early pioneers, and a new age of photography entered the Santa Barbara scene. While documentation continued to provide “butter and egg” work for photographers, several of them were also proponents of Pictorialism. They believed that photography was an art form, and that pictorial beauty should be the goal of the photographer. James Walter Collinge, whose work is the subject of the latest Santa Barbara Historical Museum exhibit, created atmospheric portraits and images using soft focus techniques and manipulation of development and printing processes and materials to express his unique artistry.

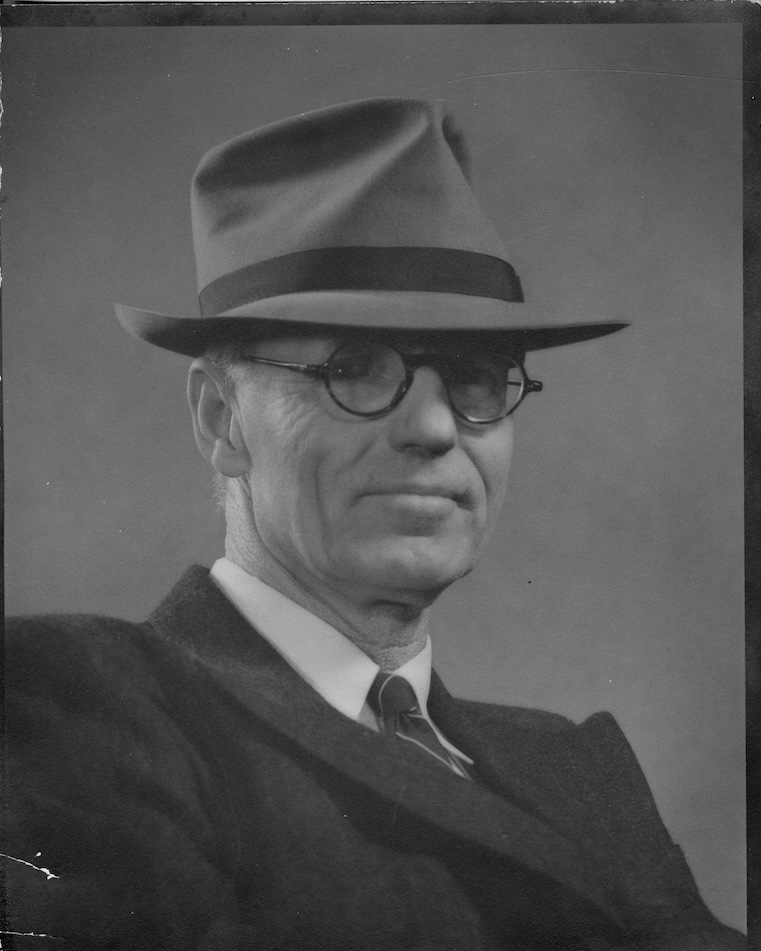

Born in Montana in 1883, Collinge bounced from town to town and state to state due to his father’s work for the railroads. His interest in photography was fostered when he worked for a photographer in Oregon.

By 1906, Collinge was married and lived in Southern California. In 1921, he and his family left Pomona, where he had co-owned a stationery store, and came to Santa Barbara to fulfill his dream of making a living through photography. Almost immediately, the newspapers began using his photographs of yachting events. By 1924, he was giving exhibitions of his work at his studio on State Street. And by 1925, his reputation had begun to spread worldwide as galleries and salons and magazines exhibited his award-winning photos.

Pictorial Artistry

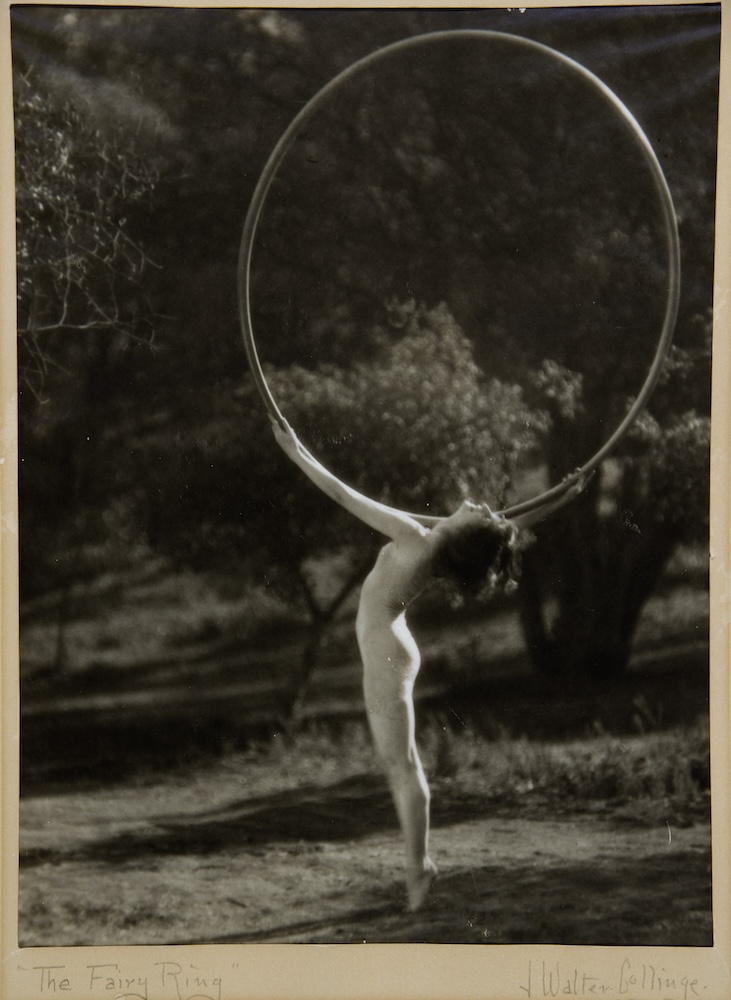

Collinge’s most famous pictorial photograph is titled The Fairy Ring and depicts a young woman posed in an extended arc holding aloft an enormous metal ring against an indistinguishable dark landscape. The model was Doris Humphrey, who was an early student of modern dance and had joined Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in their dance company before starting her own.

When the photo was exhibited in London in 1926, the reviewer said that the lines were delightful and the lighting exceptional and one hardly realized that the charm of the picture was largely due to a nude figure. Another reviewer said that Collinge’s photo displayed “what may be called French Grace,” a concept that goes beyond meticulous craftsmanship and imbues the work with charm and beauty and insight.

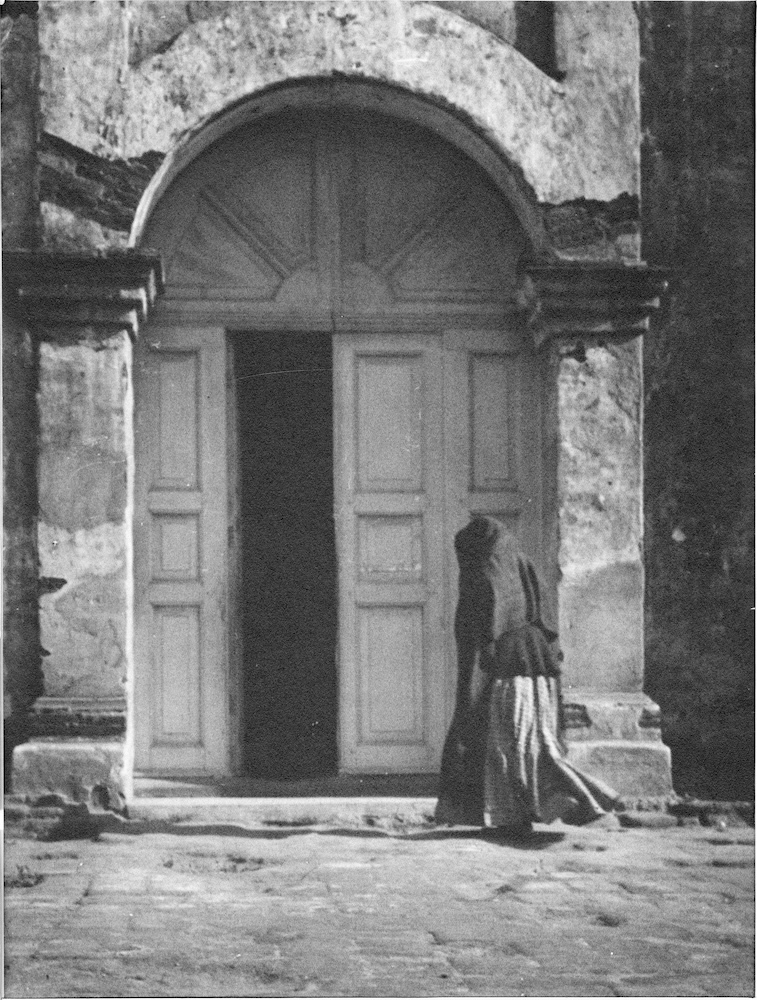

Collinge’s pictorial photo Mission San Luis Rey reveals his use of light and dark and soft focus to create a profound sense of anticipation and mystery. The woman whose head is covered with a dark rebozo seems to be hurrying into the sliver of an opening, kicking her skirt in her haste.

Collinge also hand-tinted photos, using a painterly technique to evoke a softness to the image. In Butterfly Beach, he used a few tones punctuated by the solid dark at right which separates the reflection on the sand from the sky. This photo is of a familiar scene, the view from Butterfly Beach looking back toward town.

As Collinge’s reputation continued to grow, his work appeared more and more often in magazines and reviews. His photo “Wine, or a Dance” was published in the July 1926 edition of Boston’s American Photography in which the reviewer from the Pittsburg Salon wrote, “Here we have one of our new workers of last year, Mr. Collinge, who has repeated this year with a greatly improved exhibit. Of course, his ‘Cypress and Stone’ is a unique thing but his ‘Wine, or a Dance?’ is particularly strong and extremely well-named. The two couples at the table are well arranged and tell a definite story.” Taken at Paseo Nuevo during Fiesta, Collinge has captured the staged flirtation between the couples.

The Story Behind a Picture

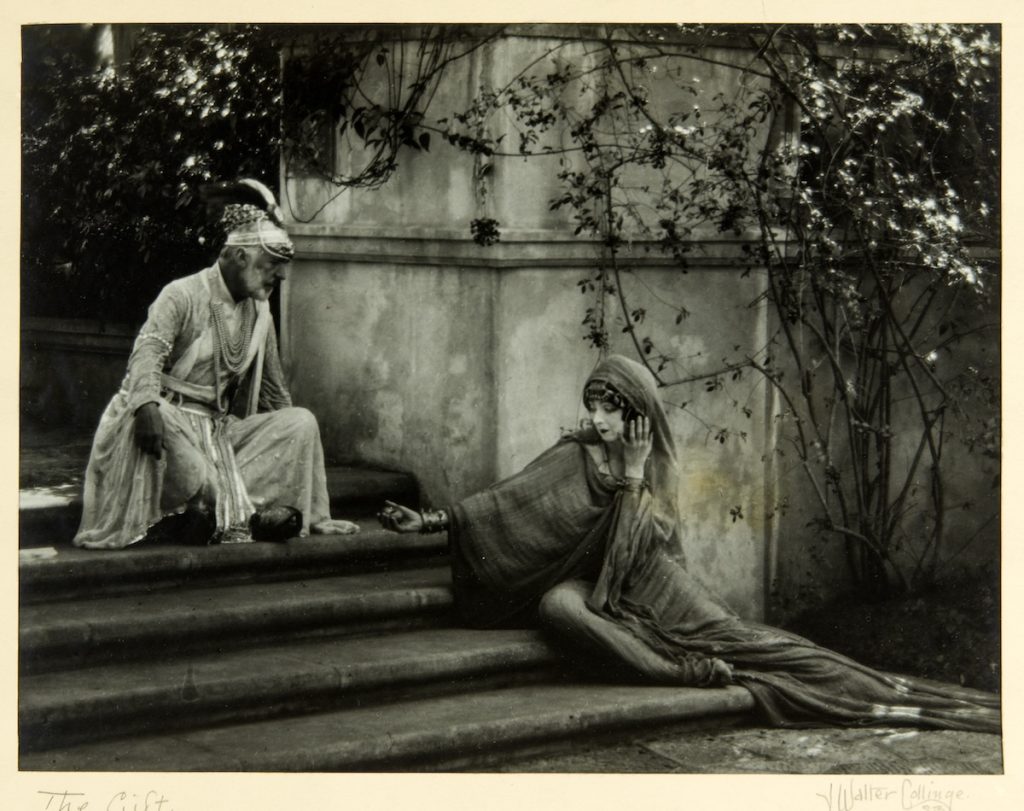

Labeled simply The Gift the photo shows a woman handing “a gift” to an elaborately costumed character. Evocative on its own, the history behind the models and the scene itself reveal an important piece of Santa Barbara’s past. The bejeweled and draped king is the artist Albert Herter, and the courtesan is the dancer Ruth St. Denis.

Herter was a world-renowned artist from a distinguished East Coast family who made Santa Barbara his home in 1913 and established an exclusive hotel he called “El Mirasol.” Herter was known for his mural work, two of which hang in the downtown library. Many others reside in state houses and other institutions throughout the world.

Ruth St. Denis was a modern dance pioneer and was considered the first lady of modern dance. She and her partner, Ted Shawn, formed a dance company, Denishawn, and trained two local girls, Martha Graham and her sister Georgia. Ruth had been performing in Santa Barbara for years and was famous for her performances by the lotus pond of artist Charles Frederick Eaton’s estate in Montecito. (Later Lolita Armour’s El Mirador.)

In Santa Barbara, the Herters were involved in community affairs. Adele was a founder of the Community Arts music branch. Together they created the Community Christmas Tree (today’s Tree of Light) along with the pageantry and tableau vivant for the community celebration. Albert taught at the School of the Arts, and he created extravaganza benefit productions to raise monies to support the work of the Community Arts Association.

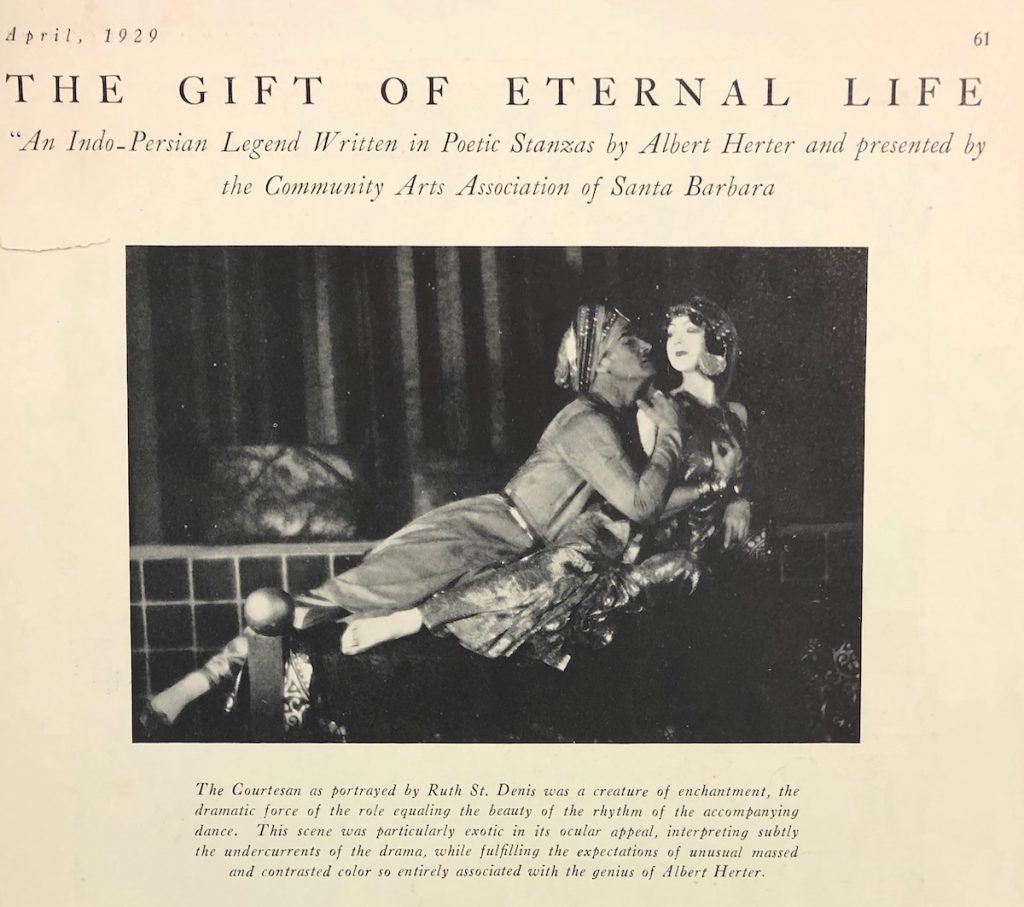

Herter’s last extravaganza in 1929 was one he’d written himself and called “The Gift of Eternal Life.” Advertised as “An Indo-Persian Legend Written in Poetic Stanzas,” it featured silent film star and former Community Arts Drama director David Imboden as the prince, Ruth St. Denis as the courtesan, and Albert Herter as the King. The hundreds of locals in minor roles included the architect Lutah Maria Riggs; Herter’s daughter-in-law Carolyn Keck Herter Bridge; the director of the School of the Arts, Frank Morley Fletcher; and nationally known violinist and local resident, Roderick White. The production at the Lobero Theatre was so popular that they extended the run.

The Depression

At the time Collinge photographed The Gift,the prosperity and enthusiasm of the 1920s would last 7 more months. And then, on October 29, an unregulated and teetering stock market crashed, sending the nation into a disastrous, lengthy Depression.

Collinge had always had his “bread and butter” work, and in the 1930s he continued taking photos of homes and gardens, as well as aerial photographs for land developers and real estate agents. His advertising, however, took on a more pedestrian form. Having dipped for a short period into making motion pictures, he began selling “Cine-Kodak Motion Picture Outfits” and offered a showing of his own film reels of dancers dancing. He called his studio the “Movie Makers Headquarters of Santa Barbara.”

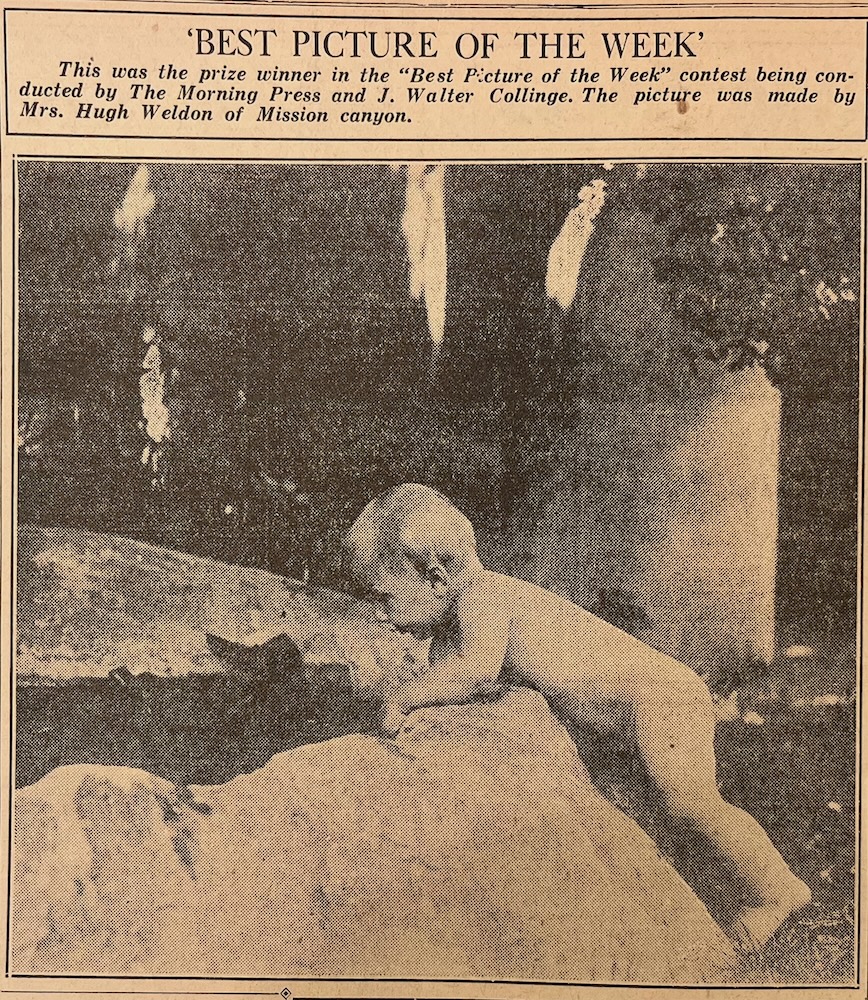

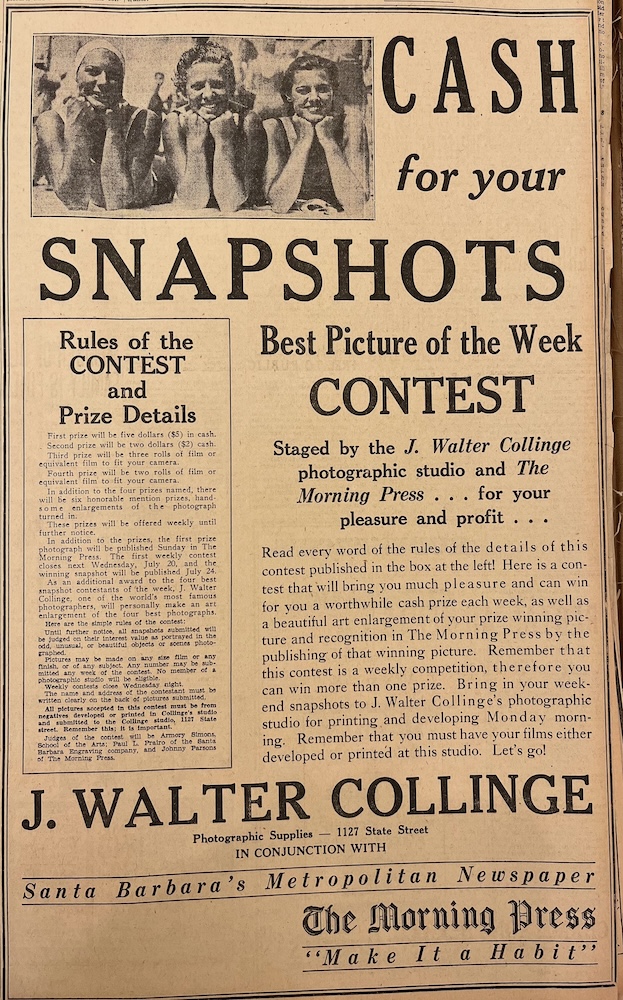

By 1932, to drum up business, he partnered with the Morning Press to create “Best Picture of the Week” contests. Winners’ entries had to be from negatives developed or printed in Collinge’s studio. Each week presented a different theme; one time it was babies, another aerial photographs, and yet another week featured photos of the extraordinary high tides that had been washing over East Beach. First prize garnered the winner $5.

Being an avid sailor and yachtsman, Collinge was appalled by the pollution caused by ships dumping bilge water in the Santa Barbara Channel. He was not alone in his outrage. The City had answered all complaints with a sigh, saying it would be too difficult to catch these ships. Collinge then sent the City Council photos he had taken of the Union Oil Company tanker Los Angeles spewing bilge water near the city. It wouldn’t have been too hard to catch the polluters, he asserted, because all they needed was a small boat and a camera.

Collinge continued to take commissions for photographic documentation through the mid-1940s, but after the war his work seemed to taper off and he spent more and more time on his yacht, Scout, specializing in marine photography. James Walter Collinge shuffled off this mortal coil near the advent of the Age of Aquarius in 1964.

Sources

Contemporary news articles; Camera Craft, March 1927; jwaltercolinge.com; “The Cultural Legacy of the Herter Family,” The Way It Was: Santa Barbara Comes of Age, 2017; Santa Barbara Historical Museum exhibition notes; “Isadora and St. Ruth: Birth Mothers of American Modern Dance” by Kenneth Topping at educationupdate.com, accessed Jan 20,2025; American Photography, July 1926.

You must be logged in to post a comment.