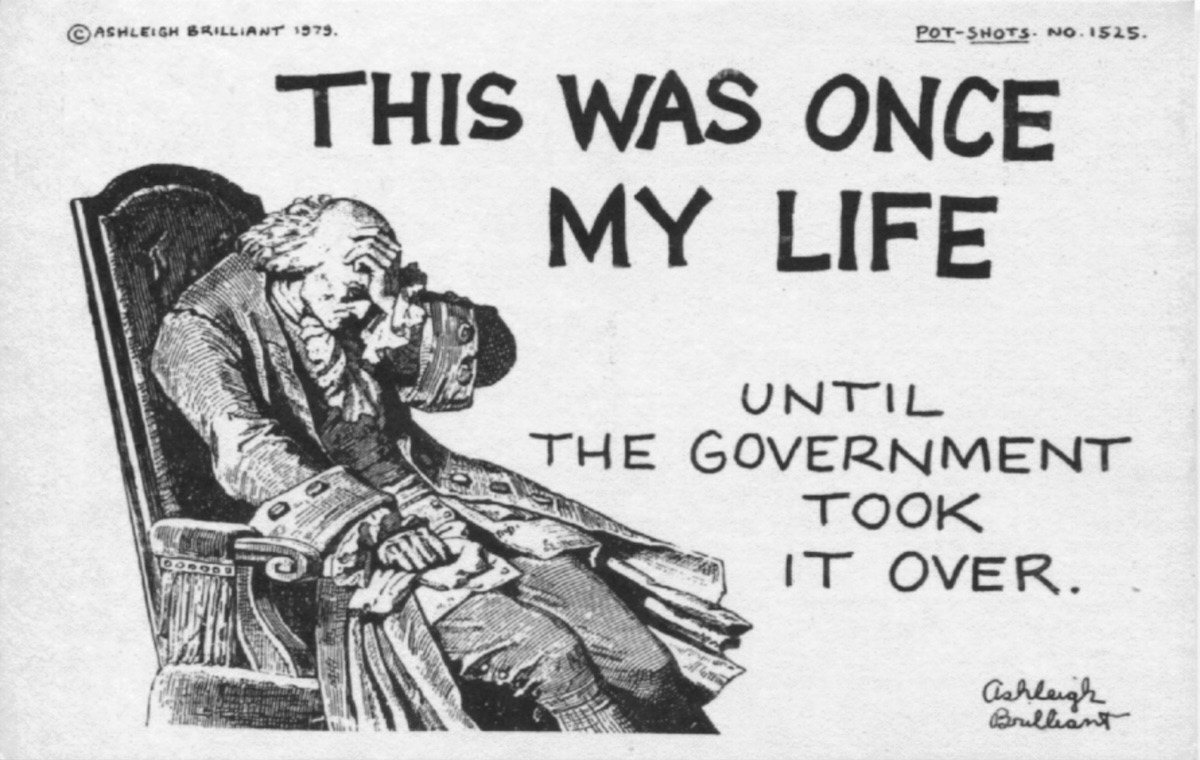

Government Work

In the evolution of our language, “good enough for government work,” is an expression which has come to mean almost exactly the opposite of what it once did. It began as a way of describing work of high quality, but somehow came to refer to what was just barely adequate. It was probably American in origin, and, to some extent, demonstrating a disrespect for authority.

You may say that I have some personal involvement in this issue, because my father, Victor Brilliant, and one of his brothers, Mortimer Brilliant (my “Uncle Mort”) were lifelong employees of the British Government, working in that branch known as the “Civil Service.”

Historically, the Government had its main offices in that part of Central London called Whitehall, and that name was used by people in general to refer to the entire bureaucracy. When I was growing up, my family lived in a far suburb of NW London, and my father, like millions of others, commuted to his “downtown” office, mostly by subway (which in England was known as “The Tube,” or, more officially, as “The Underground”).

The Civil Service was recognized as a distinct professional class, but it was also the butt of many jokes, often centering around the idea that civil servants did nothing all day in their offices but sit around drinking tea. Conversation between my parents had little to do with any actual office work but seemed to relate mostly to my father’s colleagues. I knew that he had started out shortly after World War I (in which he had served, and even been sent to France, but never saw any action. I think he was released early because he was a chronic sufferer from asthma).

At first, he was in the branch known as the Colonial Office. This would have been far more important then, when the British Empire was at its widest extent. But he was never sent anywhere, and at some point in time was transferred to another desk – the Board of Trade, which regulated commerce. By virtue of his job, however, he and my mother were once invited to attend a “Garden Party” on the grounds of Buckingham Palace, the Royal Residence. The King and Queen probably made an appearance, moving along a line of the visitors, shaking hands with the men, and being curtsied to by the women.

Somewhat ironically, my father’s government position turned out to be of crucial importance to our whole family when war came again. My mother was Canadian, and after their marriage she and my father settled in England. But in 1939, when I was just five and my sister three, she took us on what was supposed to be a vacation, to visit her family in Toronto. My father’s work kept him in England. But the War, which broke out in September of that year, caused a two-year separation.

In 1941 however, when the U.S. was not yet at war, my father was able to use his position to get transferred to the British Delegation in Washington, D.C. On his way across the Atlantic, his ship was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine, and he had a harrowing time getting off the ship and picked up by a lifeboat. In Washington, finally, our whole family was re-united, and we lived there for five years.

I still never learned much about my father’s government work – but he did once take me downtown in Washington to visit his office – and I have a nice photograph of him sitting there at his desk and looking very official.

Unfortunately for us, when the war was finally over, my father’s job required him to go back to England, this time taking his whole family with him. And the England we had left seven years before was now a country partly in ruins from all the bombing. And unlike America, it was also – due to many Government regulations and restrictions – a land in the throes of what was called “Austerity,” which included rationing of food and many other items. Some other countries, including those which had been conquered and occupied, recovered relatively quickly (thanks partly to American aid). But miserable conditions in England persisted for years.

(And aid from the U.S. was skimpy, now that Britain had a Socialist

government.)

The only benefit I can remember our family receiving from my father’s job was the stationery he brought home (perhaps illicitly). But that was probably considered good enough for Government work.