Real or Fake Van Gogh?

Gloria, who wishes she were as lucky as the picker who found a so-called Van Gogh, sent me a Wall Street Journal article about a small 18×16” painting at the center of a $15 million dollar battle. Is it a real Van Gogh? The world of scientific art analysis says it is a Van Gogh (the opinion of the LMI Group from NYC), yet the many connoisseurs at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum say it is NOT. The conflict – art and/or science in fine art authentication – has raged since the dawn of the technical revolution.

The former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas Hoving, world famous for his books on the primacy of the eye of the connoisseur, opines that an expert’s vision and gut sense are much more reliable than any science. In the Van Gogh case we are talking about some big money for a little work of art – if it is authentic, the owners might sell for $15M or more. And on the heels of this controversy, the art world sees the launch of startup scientific art authentication companies, such as the aforementioned LMI Group.

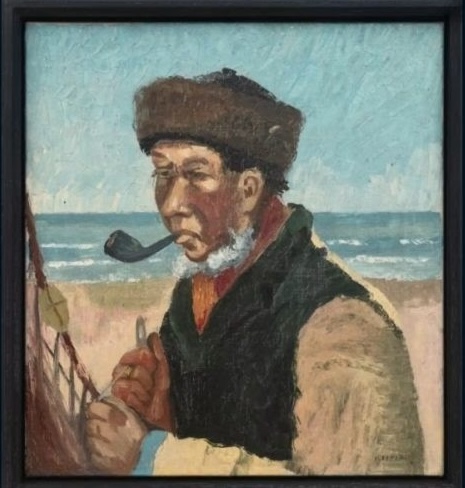

The painting was found in 2016 at a Minnesota garage sale for $50, and shortly thereafter photos were sent to the Van Gogh Museum which said “NOT” Van Gogh. The picker/owner who found it approached the LMI Group, who bought it for an undisclosed amount. Thus began the costly (to the tune of $30K) research into authentication of the little image of a strange country fisherman shown in ¾ pose, smoking a short pipe and mending nets. For the many arguments that the Van Gogh Museum has against this attribution, LMI has counter arguments. For example, the colors are muted and somber, and although the world knows him as a colorist, he also painted (rarely) in browns.

These arguments read like the future of art authentication in the AI world. The LMI Group, in an almost 500-page scientific exposé, claim that their science proves the painting was painted in 1889, towards the end of Van Gogh’s life when he was suffering at the Saint-Paul de Mausole asylum in the South of France. This report was sent to the Van Gogh Museum after the Museum had summarily dismissed the original (picker/dealer) owner’s request for an opinion of authenticity. The LMI Group issued a press release on January 31, 2025 – after the Museum had received and reviewed their report – reporting that the Museum once again deemed the work “NOT” a Van Gogh. Disappointing!

Museum directors like Thomas Hoving would have insisted that the connoisseur has the last word, thus the Museum wins. Remembering $15M plus is at stake, LMI’s report is a mixture of old-fashioned connoisseurship, cutting edge science, and scholarship – not surprising, as one of LMI’s directors is the former head of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The press release from LMI Group states that new startup art authentication companies – like theirs – aim to “expand and tailor the resources available for art authentication, integrating science and technology with traditional tools of connoisseurship, formal analysis, and provenance research.” If provenance is important, why can’t the LMI Group explain why the painting was found in a cold garage in Minnesota?

Since a Jackson Pollock was found in a dumpster in 2006 during a picker’s dumpster dive, that work was subjected to scientific analysis – 2006 style – of the paint, the board, and the technique – and was finally inconclusive. But there are over 350 un-attributed so-called Pollocks out there today. One fake sold for $17M. Since then, new scientific approaches to art authentication have gained popularity and have become pricey and highly technical – but these approaches are not yet mainstream. The science tools used? AI-generated visual analysis, chemical pigment tests, fiber tests, and a test of the glaze used; in this case egg white, a typical practice of Van Gogh. The LMI Group claims to have found a strand of male red hair in the paint. A mathematical analysis of the handwriting style was undertaken (the work’s title – ‘ELIMAR’ – matches another Van Gogh handwritten title to 94% accuracy). The stroke, the length of the letters, and the angle and width were analyzed forensically.

If you are interested in hearing the expert connoisseur’s side of the expert vs the science argument, read the classic book by Thomas Hoving on detecting works that are NOT authentic – False Impressions: The Hunt for Big Time Art Fakes – in which Hoving embarrasses some big collectors and major museum collections.

You must be logged in to post a comment.