The Hippie Trail and the Arlington: A Rick Steves Intersection

The world knows and loves Rick Steves – our shared Global Citizen whose dispatches from the Olde World edify and ennoble. Let’s imagine Rick. His blue button-down shirt is neatly tucked into dark blue jeans, his brown leather shoes are well-worn, pliant, and have thick clod-hopper soles, his inimitably cheery baby blues smile from behind frameless glasses. The guy’s soft-serve vocal timbre and exacting locution are familiar, calming, and beloved.

But remember when Rick had a concave chest, cargo shorts, a neck beard, and a curtain of Prince Valiant hair? You do if you were hanging out with the guy in 1978. That’s the year he and pal Gene Openshaw made their dust-caked, beleaguered way from Istanbul to Kathmandu, along what was then known as The Hippie Trail.

“It was all about a 23-year-old kid,” Steves says with mild amusement. “I wasn’t a travel writer, I was a piano teacher. The Beatles had long since gone to see the Maharishi, India was the destination. The hippie trail was the thing people did in the ‘60s and ‘70s.”

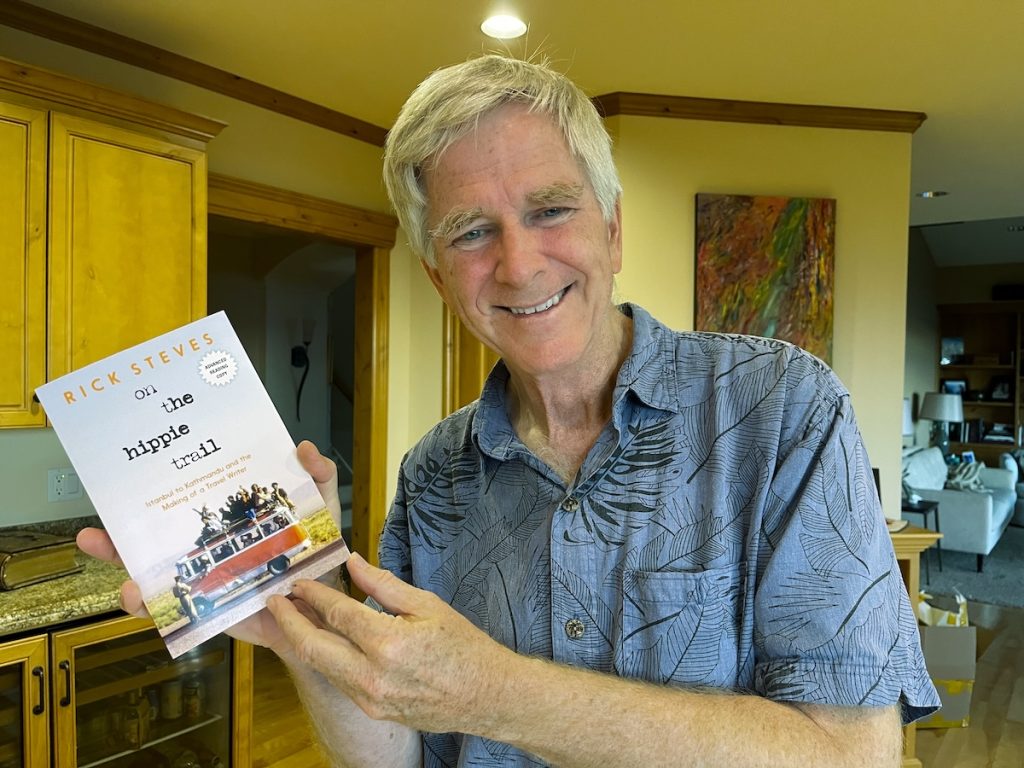

So easily summarized! The actual event was not quite as tidy. The freewheeling, heartfelt, and occasionally comic pilgrimage is forensically described in Steves’ new book, Rick Steves and the Hippie Trail: Istanbul to Kathmandu and the Making of a Travel Writer. During the COVID lockdown, Steves had rediscovered his youthful journals of the trip, now nearly 50 years past. It all (as they say) came rushing back.

“I didn’t know a single soul between Istanbul and Seattle, and nobody knew me,” Rick says avidly. “And there was a real scarcity of good information – this was raw travel, travel with abandon. I wanted to get my fingers dirty in these cultures. I wanted to get out of my comfort zone. I wanted culture shock as a constructive thing – the growing pains of a broadening perspective.” The old ‘be careful what you wish for’ bromide seems fitting here.

The charmingly named Hippie Trail was short on tie-dye and long on antiquated, wildly overstuffed trains and buses, weirdly dawdling customs stops in the whistling middle of nowhere, intense heat, the vertiginous Khyber Pass, and clustering insects from one of the circles of hell. The Hippie Trail would test both boys’ mettle; and mark the beginning of Steves’ evolution from curious traveler to politicized global empath.

“To this day, I think of India as my favorite country because it rearranges my cultural furniture in a beautiful way. And it humbles you. Americans tend to be very, very ethnocentric. We think we’re exceptional. The only thing exceptional about us in God’s eyes,” Steves says with a flinty smile, “is our ability to think that we’re exceptional.”

Ears, Teeth, Eyeballs, and All

Arriving on the Continent, Steves and Openshaw stayed a few nights with a sweet Bulgarian family Rick knew from earlier European travels. India and South Asia were new to the 23-year-old, but Europe was, even in that youthful epoch, a long-familiar stomping ground to the peripatetic and gregarious Steves, whose Continental network was already rife with friends. On leaving Bulgaria, Rick and his buddy Gene were fêted with a local delicacy – lamb’s head. The name is not a fanciful culinary conceit.

“They taught us how to eat it,” Steves scribbled in his journal with youthful brio. “The tongue and eyeballs were supposed to be best. [Our host] Datko left only the bones and eyelashes on his plate. I pocketed some teeth for souvenirs.” Later in the trip, Steves would fleetingly pine for the more familiar fare of Europe, where animal face is only very occasionally served up, typically with a buoying garnish.

From Bulgaria to Istanbul to Iran to Afghanistan, Steves’ journaling is a frank record of two young Americans abroad, two strangers in a strange land (all thanks to Heinlein). Steves’ journal entries are real-time, practical with detail, and concerned more with fidelity to the moment than performative charm. “When I wrote that journal, it was for me, I didn’t write it for anybody else,” Rick says. “This was a glimpse of me before I was a travel writer.”

The result is an unexpectedly moving document. The book is given unadorned power through its plainspoken recording of those moments that define the united human race. Steves’ journal entries – laudably uncorrected for grammatical missteps, changes in verb tense, etc – are sublime. His writing at intervals swerves into a heartening gee-whizness, and at other times into stirringly youthful poesy. The effect is a pitch-perfect setting for those quietly explosive moments on the Hippie Trail that capture us in what should be our natural element. The Human Family is not a kumbaya refrigerator magnet purchased at checkout, but human animals falling into what comes naturally. Steves records these episodes of freeform friendship with such a striking lack of embellishment you’ve no choice but to smile at the power of the reportage – and the bracing innocence of strangers energetically taking your hand in welcome.

Turkish Hammam, Iranian Pizza, Afghani Warmth. The World as it Truly Is.

Two guys in their twenties in far-flung Whereverstan – however tight-fisted their travel budget – are going to boldly taste the unfamiliar (see roasted lamb face above). Naturally while in Istanbul the guys submit themselves to an authentic Turkish massage. Steves describes he and Gene looking disconsolately at each other with one working eye each – their previously intrepid American faces half-mashed (therapeutically) against a wet marble floor as two hirsute Turkish giants do everything but break the boys in half. “I’d call the massage an all-out attack,” Steves will happily scrawl in his journal, and one can almost visualize his steamed and twisted ‘70s-era wire-frame specs perched askance on his beaming face.

In Tehran a newfound friend named Abbas (“…Abe to you Americans…”) invites them in for coffee then excitedly dashes out to get them an Iranian pizza. On a packed bus to Kabul, Afghanistan, a beautiful little girl of about ten is sitting with her mother and stares fixedly at Rick Steves – for five unbroken hours. The look of wonder on her face is inexplicably moving, as are all the photos of the locals reacting to these two American argonauts. Smiling, laughing faces crowd Rick and Gene wherever they go – jostling for a look and giddily stunned at the guys’ presence, the townsfolk’s delight filling frame after frame. In a town called Pokhara the guys try a few bites of water buffalo. “Rather than actually swallow it,” young Steves exactingly records, “we would chew all the nutritional value out of it until a tight little wad of gristle remained – which we’d place daintily on the side of our dinner plate.” If you can find a more telling description of young Americans sampling Nepalese water buffalo, lemme know.

Throughout, Steves cheerily records the wild conviviality that greets them, from city to town to remote village – the globally common human experience that unfurls when folks aren’t being harangued by leadership into fear and prejudice and all the other wholly invented crap we’ve yet to rise above.

“I believe that if more people could have such a transformative experience – especially in their youth – our world would be a more just and stable place,” Steves tells me today. “If you’ve traveled, if everybody could travel before they voted, we’d have a different world right now.” Can communing with the wider world really move that mountain?

Decades ago on the Hippie Trail a young Rick Steves stumbled onto a moment of inadvertent exaltation – one of many – on a dusky terrace in Afghanistan.

“I went out on the hotel balcony to speak with the old cleaning man. ‘Look,’ the man said dreamily. ‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ We both stood motionless, watching as the sun sank behind the distant mountain.’” Young Steves took pen to paper that evening – now nearly 50 years past – to record the moment. “I guess,” he wrote, “people all over the world enjoy the same things.”

Rick Steves will be speaking on this and other globe-hopping topics at Santa Barbara’s Arlington Theatre on Feb. 21.

You must be logged in to post a comment.