Welcoming 1925

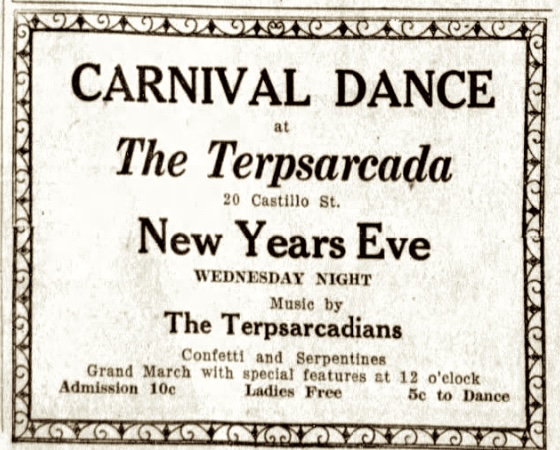

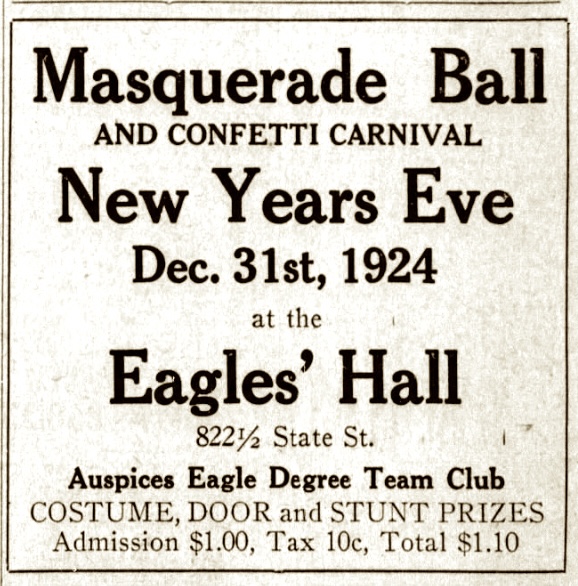

No popping champagne corks announced the arrival of the new year in 1925. Prohibition still ruled the land. Nevertheless, Santa Barbarans could look back with pride to 1924 along with enthusiasm and hope toward 1925. The Morning Press headline blared, “Santa Barbara Greets the New Year with Noise and Church Services.” The dance floors were bustling as local lodges and hotels hosted celebrations which took on a carnival spirit. The Recreation Center was hopping early on, and dancers at Terpsarcada, the former Beach Pavillion at 10 Castillo Street, shimmied and fox trotted the year away. To add to the general cacophony, hundreds of motorists cruised State Street, said the Morning Press, “with exhaust pipes open and the horn button taped down.”

There was reflection and jubilation at Watch Night services, which commemorated the end of slavery as the Emancipation Proclamation had gone into effect on January 1, 1863. Participating were All Saints-By-the-Sea Episcopal Church in Montecito, the First Presbyterian Church, the First Baptist Church and the First Methodist churches.

Disturbingly, however, one of the New Year editorials discussed the “National Disgrace” of lynchings. Citing statistics published by the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, there were 16 lynchings accounted for in 1924, with 45 more prevented by officers of the law. But for the vigilance of the police, the report asserted, the total would have been 52, only a few less than the high record established two years ago. The Morning Press editor remarked, “So the low record established in 1924 is not to be taken as indicative of any decided diminution of the lynching spirit. The devil of hate and intolerance and brutality has not yet been exorcised.”

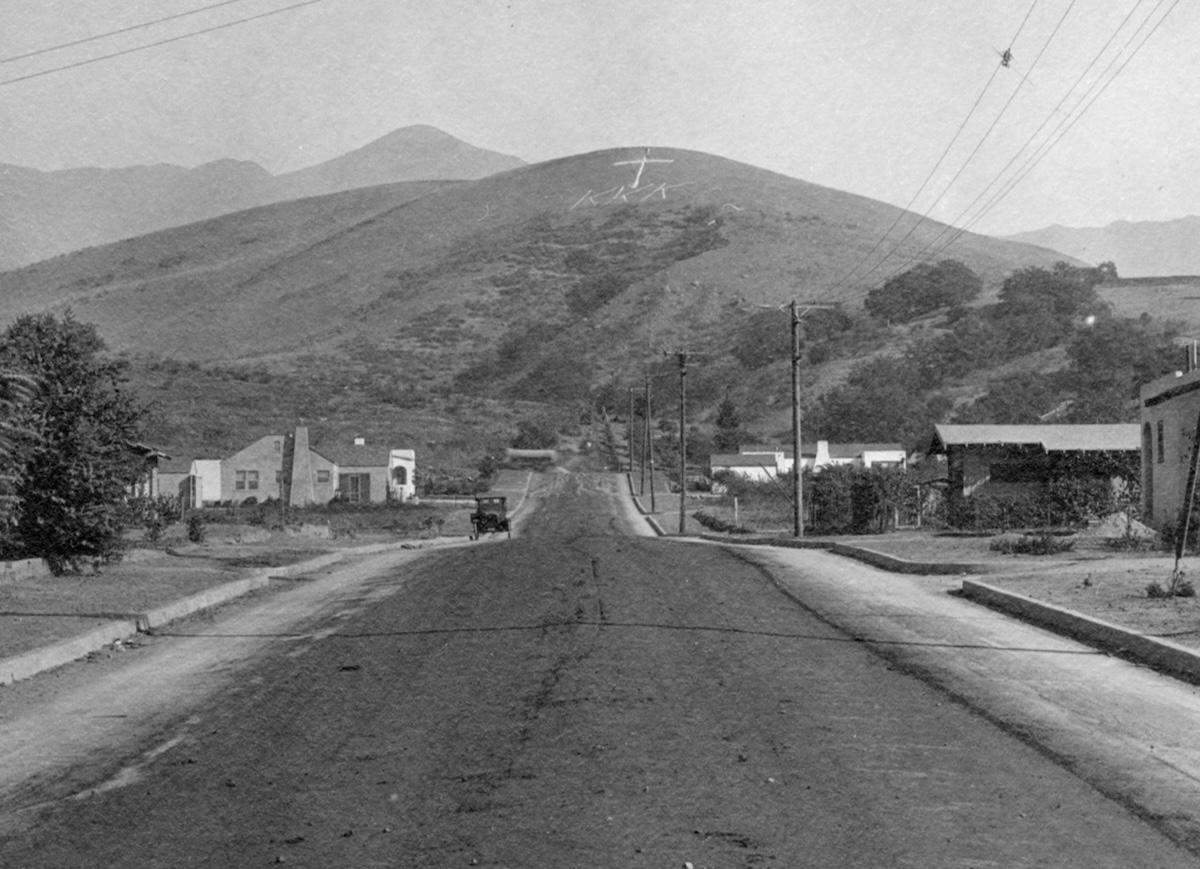

The Morning Press editor failed to mention that in 1923, the Ku Klux Klan had recruited over 2,000 members from Santa Barbara County with the promise of preserving American traditions and protecting American women. A burning cross on a hillside of Sycamore Canyon signaled meetings. That membership would quickly dwindle to near-nothing when in March 1925 the Grandest Dragon of the Empire, D.C. Stephenson, kidnapped and raped Madge Oberholtzer, thereby exposing the Klan’s true violent and corrupt nature.

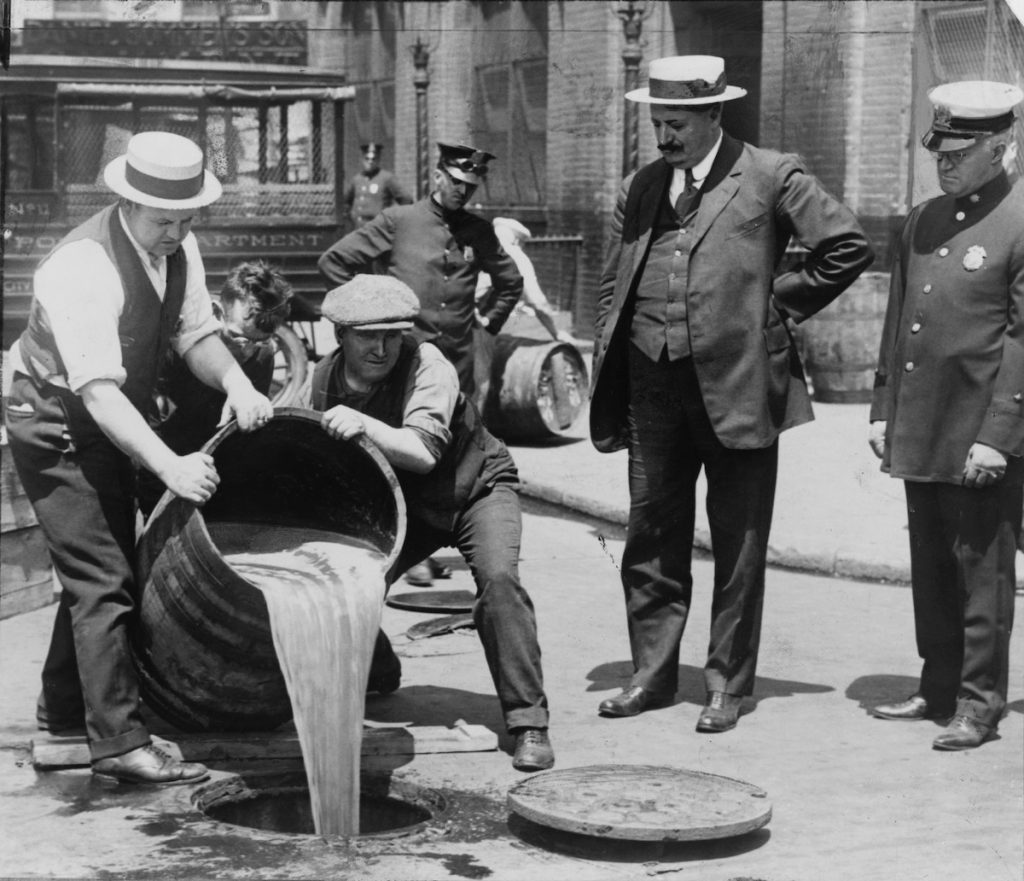

Tottering into Another Teetotaling New Year

Officers of the law were out in force on New Year’s Eve and both Sheriff Ross and Police Chief Desgrandchamp warned the public that they would not be looking the other way if hip flasks were brandished. When the Law received word that 50 cases of whiskey had been unloaded in Santa Barbara from a northern rum runner’s cache, they went on an exhaustive search for the hooch but came up empty handed.

One scofflaw, Ora L. “Speed” Landreth, however, did not escape the long arm of the Law when he was picked up on State Street with, according to the police report, “a pint of whisky on his hip and another on his breath.” As officers led him to the jail house, he broke out in song, singing in a rich baritone that “it ain’t gonna to rain no moh, no moh!” Once incarcerated, Landreth pretended his cell door was an upright bass and plucked out imaginary tunes on the bars while he treated an unappreciative audience to his complete repertoire of jazz melodies.

The police had enjoyed better luck earlier in the day when they raided the home of E. Harrington at 934 Alphonso Avenue. There they found five bootlegged cases of bonded Scotch whiskey, a barrel of corn whiskey and several bottles of white mule (aka moonshine) all ordered for several local New Year’s patrons. Bootlegger Harrington pleaded guilty, paid a fine of $300, and announced defiantly, “I’ve drank whiskey all my life, and I’m going to continue to drink it. You’ve got this booze, but I’m going up north to get some more!”

Cultural Entertainment

At the end of 1924, Santa Barbara could boast two new performing arts theaters (the Lobero and the Granada), as well as several movie houses. The Community Arts Association sponsored both a drama and music branch, and it supported the School of the Arts. The Civic Music Committee brought top notch orchestras and other professional music groups to town. Local booking agents, like Mrs. Clara E. Herbert, a leading spirit in the musical world in Santa Barbara, had developed the Philharmonic Course and Artists Series for the Potter Theatre.

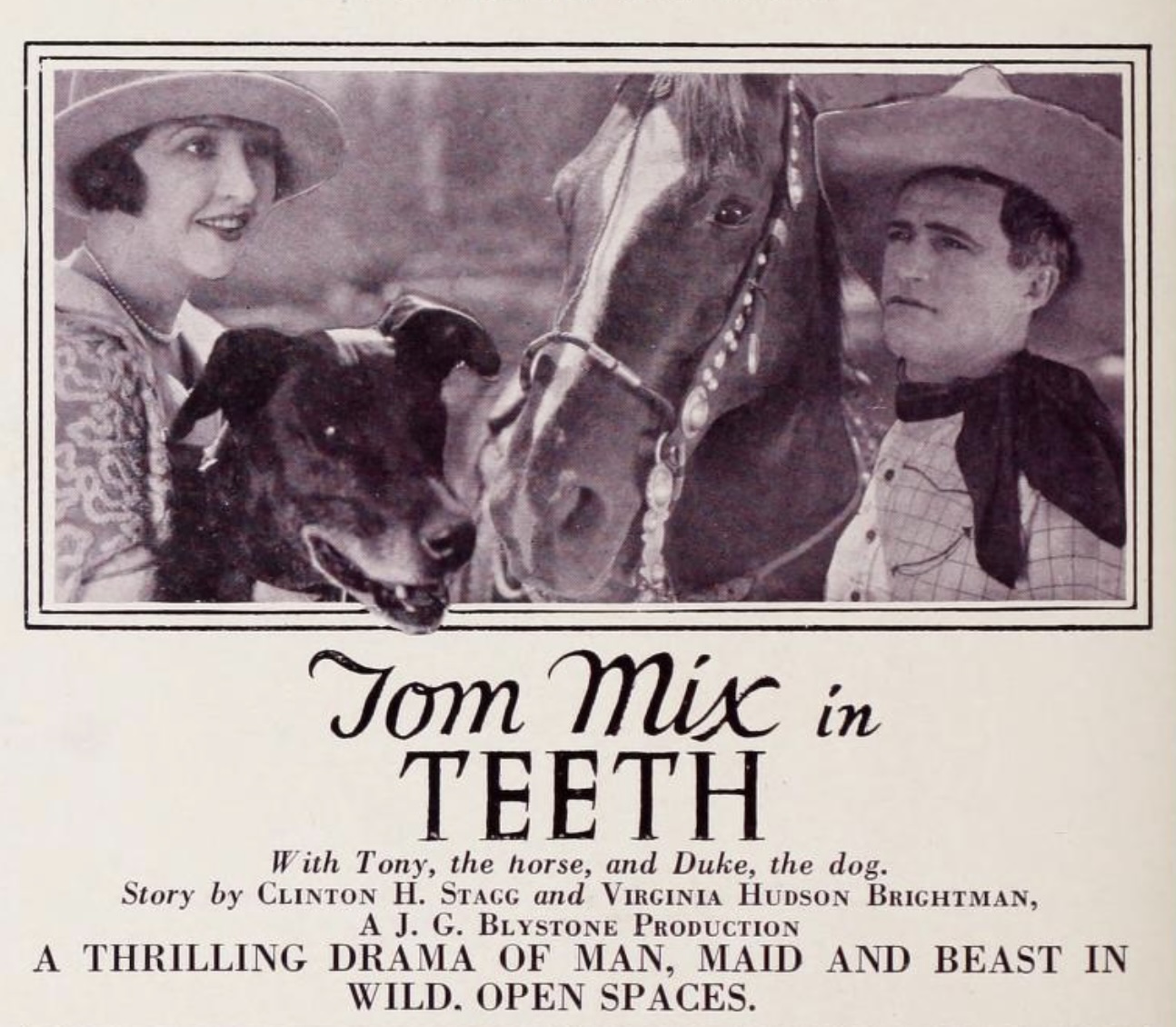

For January 1925, the Civic Music Committee brought the Philharmonic Orchestra of Los Angeles (LA Phil) to the Granada Theatre. British musical phenom, Arthur Bliss, who had resided in Santa Barbara for a few years past and become involved in all aspects of Santa Barbara music, gave a free preconcert lecture for the Granada concert at the Lobero Theatre. Showing its versatility, the Granada followed up the next day by presenting two days of Vaudeville movies with Dolly Dumplin & Co “in a remarkable juvenile comedy,” The Little Runaway, as well as “Tootsie Wootsie.” At the California movie house, Tom Mix together with Tony the Horse and Duke the Dog thrilled moviegoers with Teeth.

The Potter Theatre started the new year with a concert by the Chamber Music Society of San Francisco. Headed by violinist Louis Persinger, the principals of the organization would spend two seasons (1926-27, and 1927-28) in Santa Barbara as the Persinger Quartet, where they were sponsored by the Community Arts Association. Persinger had appeared as a soloist with the Community Arts Orchestra in 1922 and performed throughout that year for the Sunday Evening Musicale Committee which brought the entire Chamber Musical Society to various Montecito homes.

For those who preferred the culture of sports, the morning was given over to donning Irish green or Cardinal red before hieing to the Daily News Building at De la Guerra Plaza. There, leather-lunged “Hippo” Espinosa would narrate the rousing details of the gridiron battle between the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame and the Stanford Cardinals. The Daily News announced that play by play would be relayed instantly over a special wire by the Associated Press and passed along via megaphone to the audience. Residents were invited to “thrill to the smashing gallop of the four horsemen and the answering surge of the sturdy Cardinals in the game to secure the National Championship.” One hundred years too late for a spoiler alert, Knute Rockne’s famous four horsemen brought on a “typhoon of speed” and swamped Stanford with a 27 to 10 score.

In another legendary game, U.C. Berkeley prevailed over Pennsylvania, 14-0, to win the East West championship. The AP article announced, “There was a Quaker meeting here this afternoon and the congregation, numbering some 50,000, was confirmed in the belief that football is a great sport.”

The Architectural Landscape

By 1925, Santa Barbara had been inching away from the Victorian Age and its architectural style for several years. Moving through Craftsman and Mission motifs, many Santa Barbarans settled on Mediterranean and Spanish Colonial styles of architecture after the 1915 Panama California Exposition in San Diego had popularized the style. The Plans and Planting branch of the Community Arts Association, under the direction of Irene and Bernhard Hoffmann and Pearl Chase, promoted the Spanish style for a uniform architectural landscape appropriate to Santa Barbara.

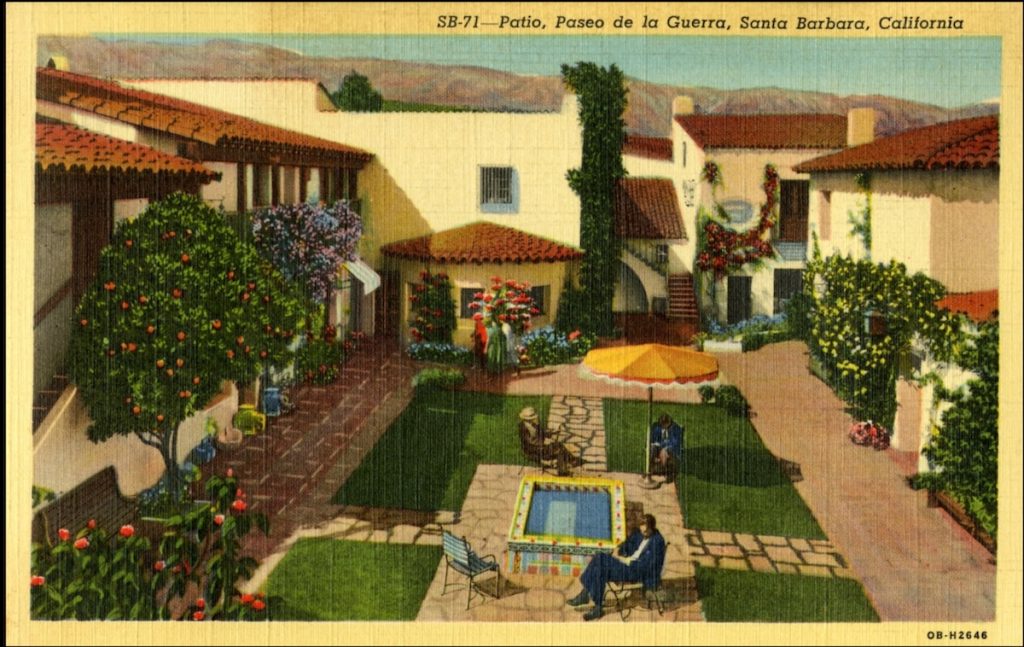

In the January 1925 edition of California Southland, Santa Barbara was featured in several articles. In addition to articles on the School of the Arts, the Community Arts Players, and Santa Barbara gardens, the Lobero was shown as an example of the new architecture. The magazine also sported ads for the businesses in Hoffmann’s new El Paseo complex, built to resemble a small Mexican village.

By 1925, several residences in Montecito and Santa Barbara, as well as downtown businesses, had been built or renovated in the new style. George Washington Smith had designed a Spanish Colonial home for the Little Town Club on the corner of Anacapa and Carrillo streets, and the venerable Carrillo Adobe had seen its first restoration. Roland Sauter and Keith Lockard had designed the new City Hall to supposedly blend in with the De la Guerra Adobe, and the Daily Press Building had followed suit.

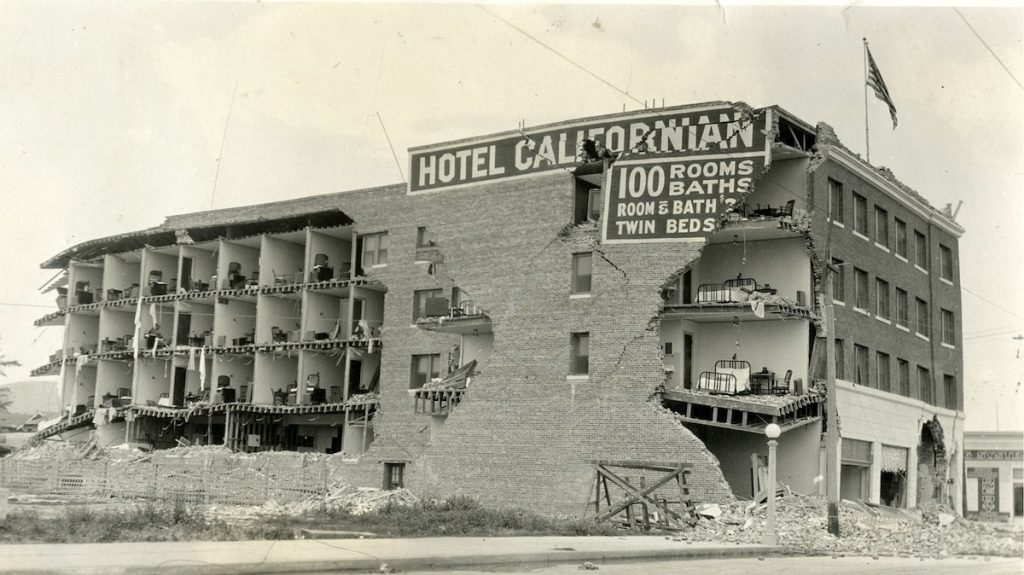

The majority of the residences in town, however, continued to look like Victorian dowagers with steep gabled roofs and elaborate wooden detailing, while the red brick business district resembled Main Street, U.S.A. On June 29, Spanish Colonial style was to get an unexpected boost when a 6.7 earthquake roared through the town and heavily damaged State Street businesses. In the aftermath, the Community Arts Plans and Planting Committee took steps to advocate and facilitate the renovation of Santa Barbara in the Spanish style.

Sources: contemporary news articles; California Southland, January 1925. For more information on the KKK in Santa Barbara, see “The Mystic Knights of the Invisible Empire,” by Hattie Beresford in the Montecito Journal, 2009; “Elias Hecht and the Chamber Music Society of San Francisco: Pioneers of West Coast Chamber Music” by Katherine Isbill Emeneth, 2013.

You must be logged in to post a comment.