It Could Be Verse

There are two famous poems which have one thing in common. What they have in common, however, might be considered by some critics a shortcoming. It is the literary practice of anthropomorphism. In case you need an explanation, that word describes any poetic attempt to endow non-human objects or creatures with human characteristics. For example, if you were writing about a candle and lamenting how quickly its brief life could be snuffed out, you would be making that object seem like a living person.

The first guilty poem on my short list is by Robert Burns, (1759-1796) who is generally considered to be the greatest poet Scotland ever produced. Even today, all over the world, people of Scottish descent are so proud of him that they gather in clubs called “Burns Societies,” and always have a big meeting on his birthday.

Most of us, Scottish or not, celebrate the coming of a New Year with Burns’ verse about “Auld Acquaintance” and “Auld Lang Syne” (which means “Old Long Since”); the poem joined to an older Scottish folk melody to form the song we sing today.

You can find the particular Burns poem I want to bring to your attention in both the Scottish dialect in which it was originally written or – if that is too cumbersome for you – in “translated” versions in modern English. It’s called “To a Mouse.” This particular creature is a field mouse, whom the author had disturbed in its nest while he was plowing one of his fields. But the piece is written as sympathetically as if it were about some human being cruelly evicted from his or her habitation. You probably know its most quoted line, about “the best-laid plans of mice and men” (which gave John Steinbeck a title for one of his novels) often going awry. And that is the essential message – that we are all potential victims of uncontrollable circumstance.

The poem is written as if speaking directly to the mouse. It is partly an apology for having caused its present plight, but also a lament for what man and mouse have in common. The poem is “thy poor earth-born companion, and fellow-mortal.” And, in the end, it’s the man who is even more to be pitied – because we humans, unlike you other creatures, not only have to contend with a possibly painful present, but may also be afflicted with unhappy memories of the past, and with fears of an unknown future.

The second poem is called “Trees.” It is by Joyce Kilmer – a man who died at the battlefront in World War I. It talks about a tree as if it were a woman, lifting “her leafy arms to pray” and having “a nest of robins in her hair.” And there are several references to breasts and bosoms. The particular type of tree is not even specified.

I need hardly tell you that mice and trees are not people. But they are not the only types of objects which our culture has delighted in humanizing. One example has to do with furniture. In Victorian times, the fact that chairs and tables had legs seemed to call for some action in the name of Decency. Strange as it may seem to us today, people who considered themselves sensitive to such issues actually put special little skirts on those exposed limbs.

More recently, the classic instance of humanizing objects was with the early automobiles. Horses had often been called Elizabeth, or some variation of that name. It was only natural, therefore, for that practice to be transferred to cars. The Ford Model T, of which an incredible Fifteen Million were produced from 1908 before the appearance, in 1927, of its successor, the Model A, inherited the equine name, and was (usually fondly) known as the “Tin Lizzie.” One popular song of the time was called “Henry’s Made a Lady out of Lizzie.”

People talked to their cars – and, considering how much time they spend together, many probably still do.

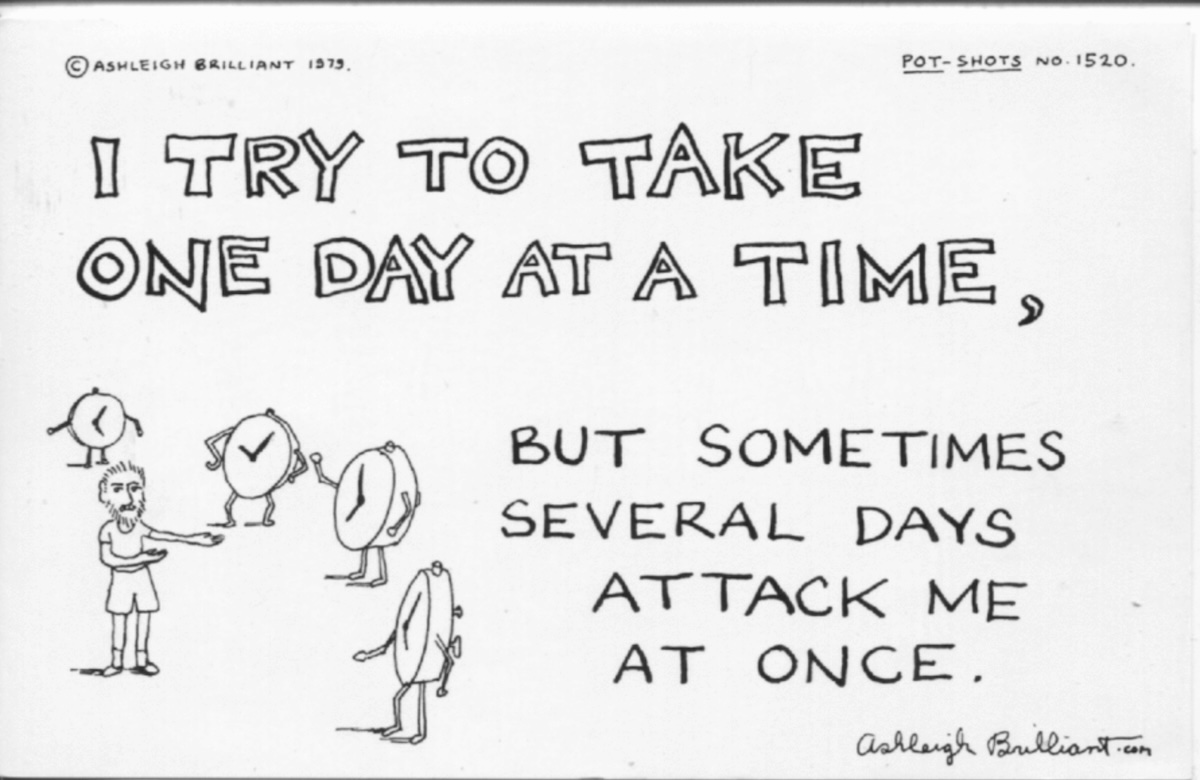

To a limited extent, the same combination of affection and frustration has materialized in connection with home computers. My own business of marketing short expressions has jumped aboard this Band Wagon with anguished utterances like these:

“My worst personal problem is that my computer doesn’t understand me.”

“My computer has no feelings – but I have more than enough for the two of us.”

“The purpose of computers is to teach us humility, patience, and obedience.”

Finally, let’s not forget nursery rhymes, such as the one that describes that scandalous affair in which the Dish ran away with the Spoon.