Something to Crow About

During the California Gold Rush, eggs cost a whopping $3 dollars each, which translates as $120 per egg today. The high price of eggs, however, did not lead to a thriving poultry business. Chickens couldn’t be herded across the plains and were difficult and expensive to transport in great numbers around the Horn. Besides, wild fowl existed in abundance and were there for the taking. Also, cuts of beef and other meats were much more affordable and easier to produce.

Though the gold petered out, the population of California increased during the next 30 years, and chickens were raised mainly in backyards where they could subsist on kitchen scraps and garden pests in return for tilling the soil with their scratching and supplying the household with eggs. Older hens became stew meat and cockerels provided the occasional fricassee.

Backyard chicken – in fact, all chickens – need grit to help them digest their food since they don’t have teeth. They pick grit up as they forage. In 1883, a Santa Ynez woman killed a fat chicken for dinner. In cleaning it, she found a small lump of pure gold in its gizzard. Reportedly, the people of Santa Ynez began enjoying chicken dinners nightly in the hope of discovering the new El Dorado.

Back then, the cost of chicken feed necessary for large production wasn’t “chicken feed.” It was very expensive. In the late 1870s, however, two inventions spurred a change – the temperature-controlled incubator and the California slipshod method. The latter was an open range system which required mobile coops moved several times a month onto fields planted with barley or corn.

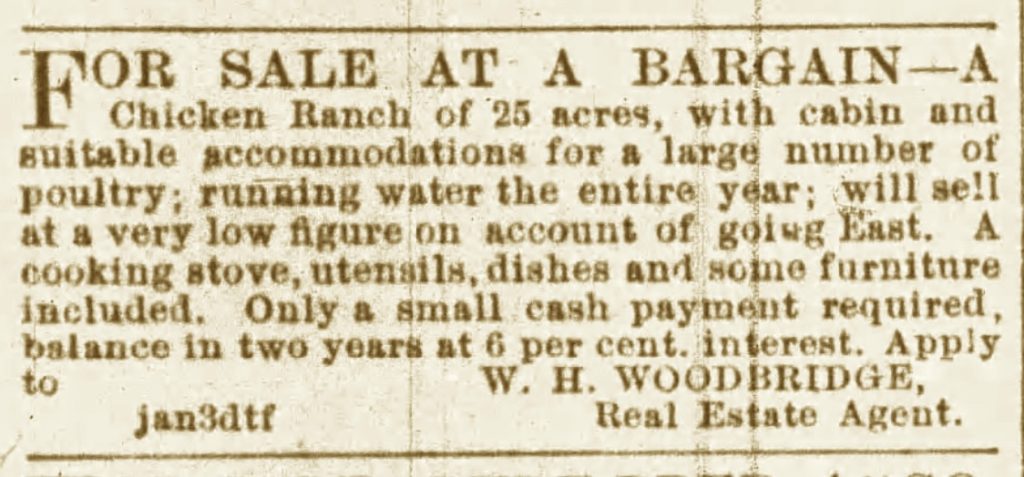

In 1877, the Santa Barbara Weekly Press published an article claiming that chicken raising was good business.” The author asserted that one could make a comfortable living from it with 5-10 acres. Several enterprising ranchers took up the call and sought to stock their land with chickens, not always legitimately.

During the spring months of 1878, over 1,000 chickens were stolen out of Santa Barbara backyards. A well-organized gang of chicken thieves was cherry picking the best stock and selling or taking them to area chicken ranches. The police ended up with egg on their faces as the rash of thefts continued, leaving area residents with ruffled feathers.

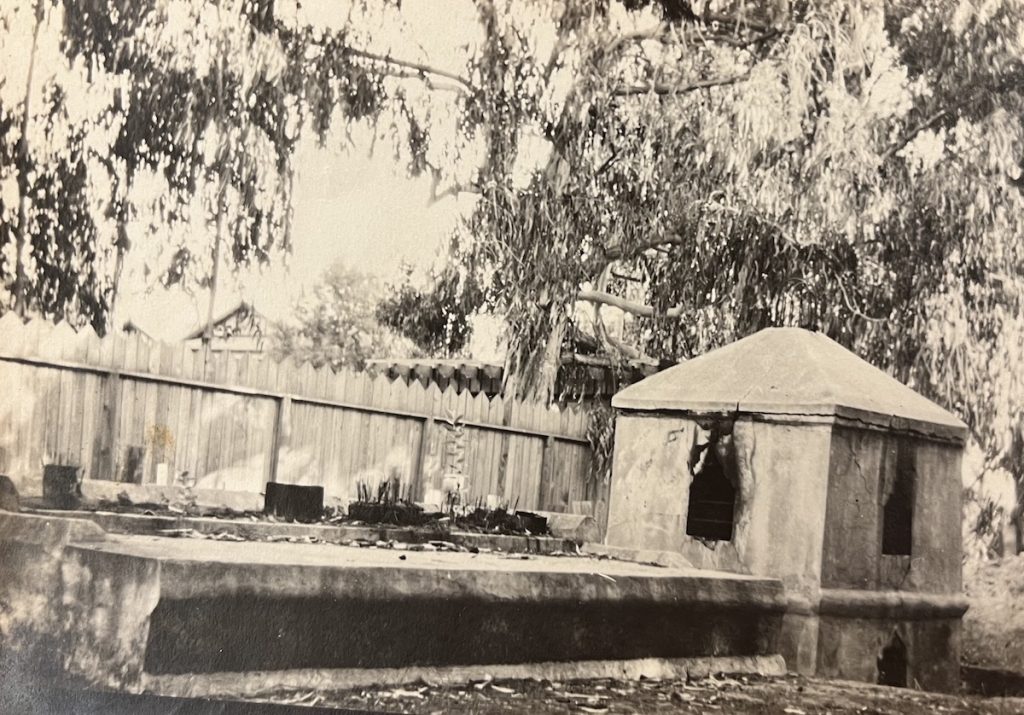

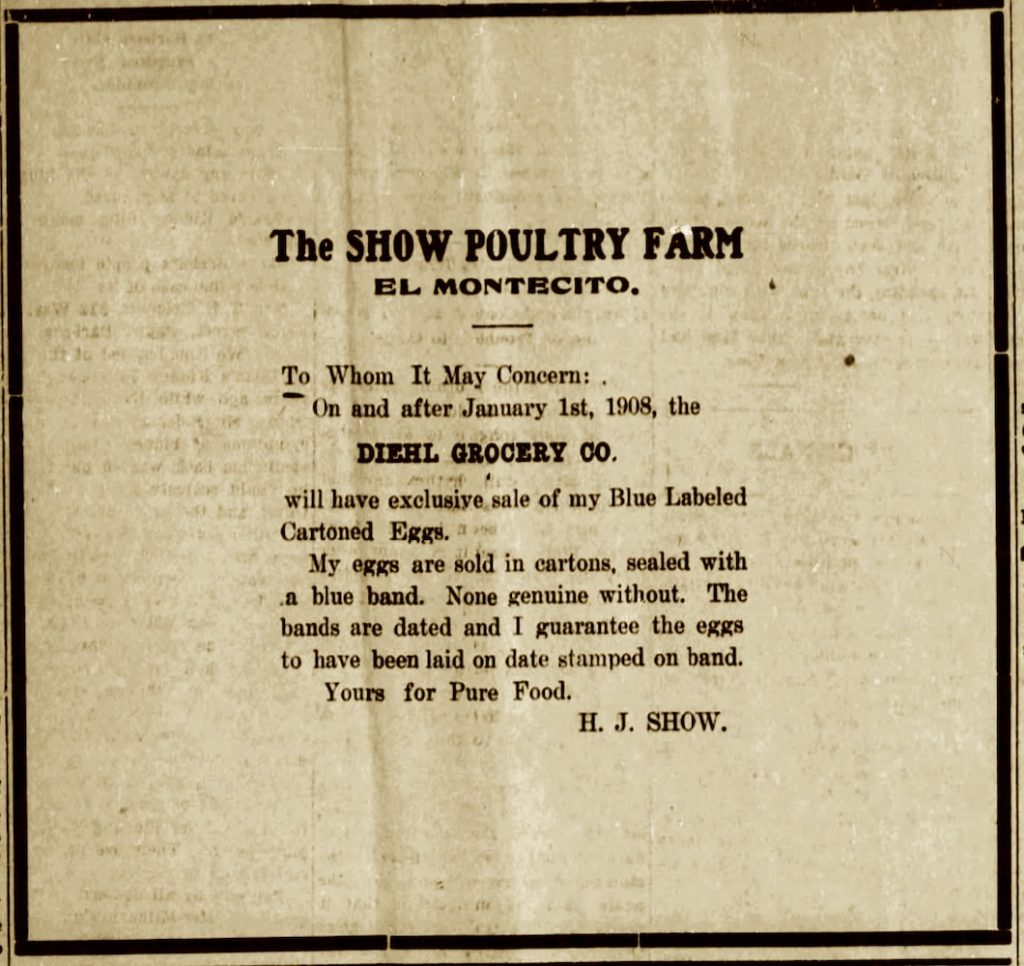

By 1905, Santa Barbara had a few successful local chicken ranches. One was Captain Mitchell’s model chicken ranch in Sycamore Canyon called Arequipa Ranch. Another local ranch was that of H. J. Show, brother to W. C. Show of the then-famous Show and Hunt grocery store. His ranch was in Montecito south of San Leandro Lane.

Chicken Lore

Chickens have had a role in the world’s religious and cultural traditions for millennia. In Egyptian temples, eggs were hung to insure a bountiful river flood. In West Africa they had a role in origin tales and ritual sacrifice. Romans used them for fortune telling before battles, and in Zoroastrianism, the crowing rooster signified the struggle between the metaphorical Light and Dark. In Christianity, the rooster was associated with Saint Peter who denied Christ three times before the cock crowed.

In 1886 in Santa Barbara, chickens had a role in a court case for the prosecution of three Chinese men accused of robbery. The counsel for the defense had asked that the witnesses be sworn in according to the custom of their home country. In the interest of ascertaining the truth, Judge Canfield granted the motion.

To do so, the entire court had to adjourn to a holy place, which ended up being the cemetery. There, the defendants were to sign an oath and cut off a chicken’s head. The counsel for the defense agreed to furnish the chickens. When they arrived at the cemetery, however, an argument arose because although the witnesses for the prosecution had chickens on the altar, none had been provided for the witnesses for the defense. They, apparently, could lie with aplomb.

Back to the courthouse the group retreated. The following day, they met again at the cemetery and each witness was given a chicken by the opposing side, along with a piece of money. Each witness then cut off a chicken’s head and, reputedly, told the truth. According to the news reporter, who had struggled mightily to understand it all, the belief in this custom was so strong that the statements made by the witnesses were often accepted for judgment by the opposing side.

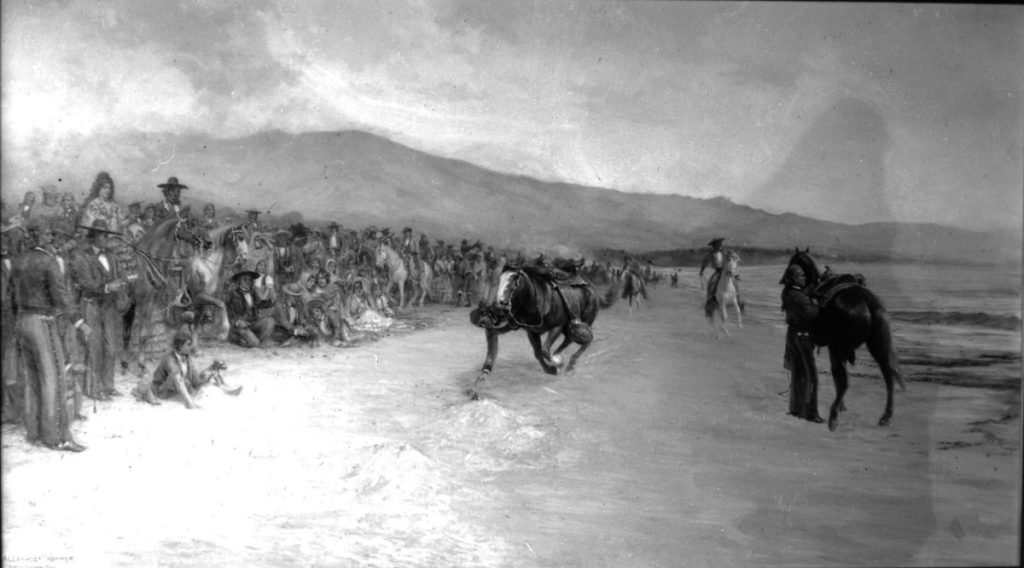

The Spanish also brought a chicken custom to Santa Barbara, that of the Rooster Pull. The Corrida del Gallo came to the New World from Spain and is believed to have originated there in the Middle Ages. For it, a rooster was buried up to its neck in the ground. Caballeros on horseback raced to grab it from the dirt, swinging it around and striking others before presenting the bloody dead bird to the women of their families. The custom became part of Native American culture in New Mexico in the late 1600s partially because the blood of the rooster became identified with bringing water and fertility to a parched landscape. Santa Barbara artist Alexander Harmer, who resurrected the Spanish past through his talented brush, painted such a contest in Santa Barbara.

Chicken Dinners

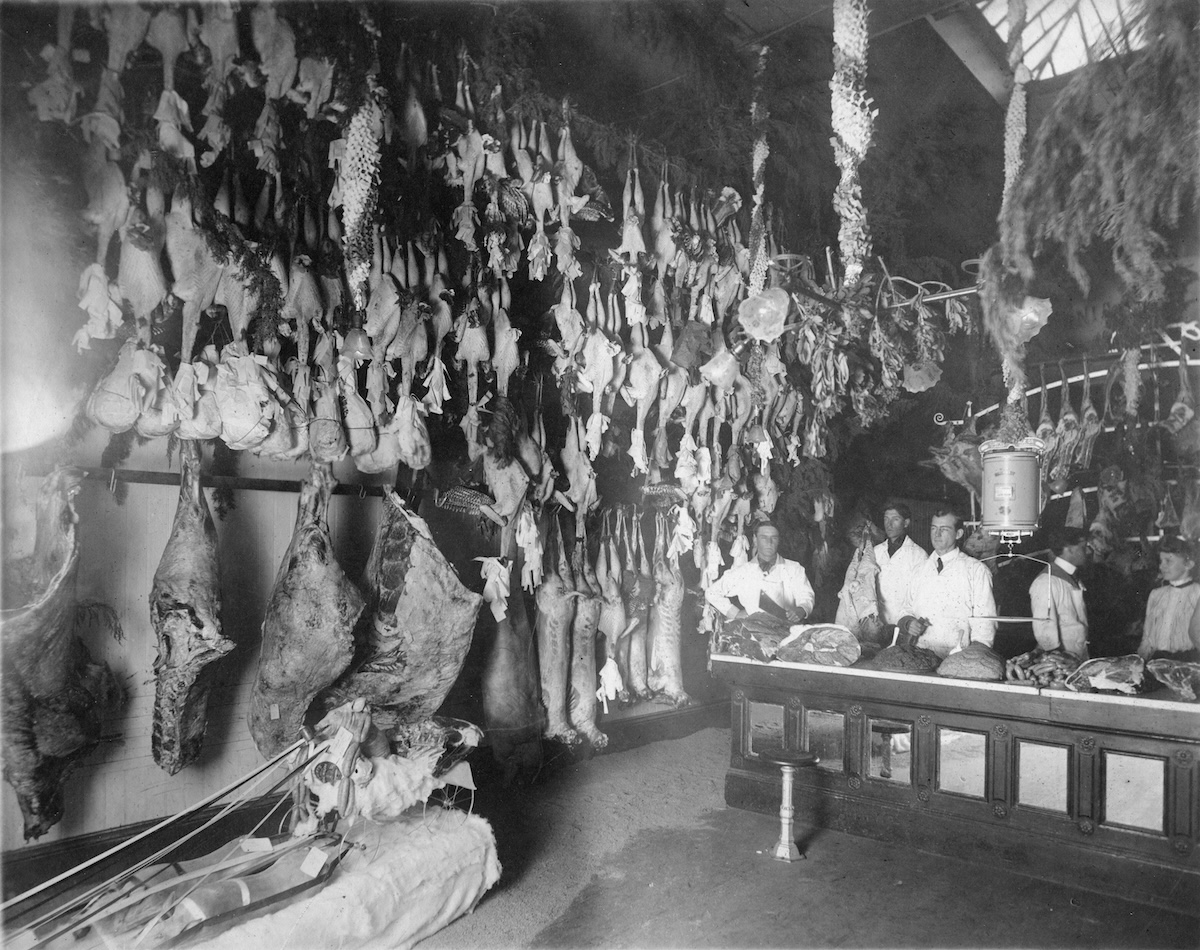

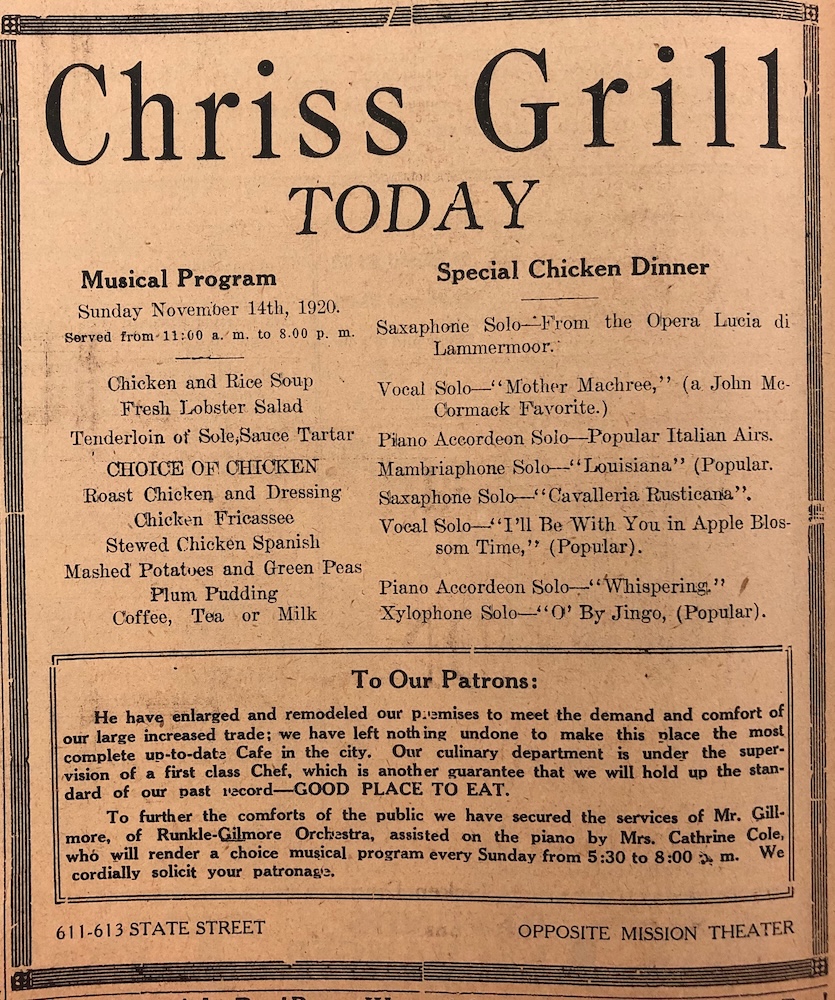

It wasn’t until the mid-1880s that chicken dinners became the star of restaurant, home, and church events. In 1888, the Western Hotel advertised Sunday chicken dinners for 25 cents, and the Home Restaurant offered a chicken dinner with mince pie. The local churches began holding chicken dinner fundraisers after the Congregational Church advertised one for 25 cents in 1890 with great results. The Salvation Army got into the act in 1898 when they turned their yard into a chicken slaughterhouse to prepare for the “great chicken dinner” to take place at GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) Hall. Three men were employed in the killing while several of the sisters dressed and eviscerated them for roasting, frying, and fricasseeing.

In 1902, the ladies of the Presbyterian church gave a chicken dinner to raise funds for a pipe organ. They were proud to present soup, chicken pie with giblet sauce, mashed potatoes, baked beans, cabbage salad, spiced oranges, and cake for 35 cents.

Not to be outdone, in 1906, the ladies of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (today’s St. Paul’s AME) gave an old-fashioned Southern chicken dinner which included chicken gumbo, baked chicken pie, ham and cabbage, sweet potato and squash pies, barbecued pork, baked sweet potatoes, and salad – all for 25 cents. The money raised would help them finish building and furnishing the new AME church on Haley Street. They hoped to entice the entire Santa Barbara community with their fine cooking.

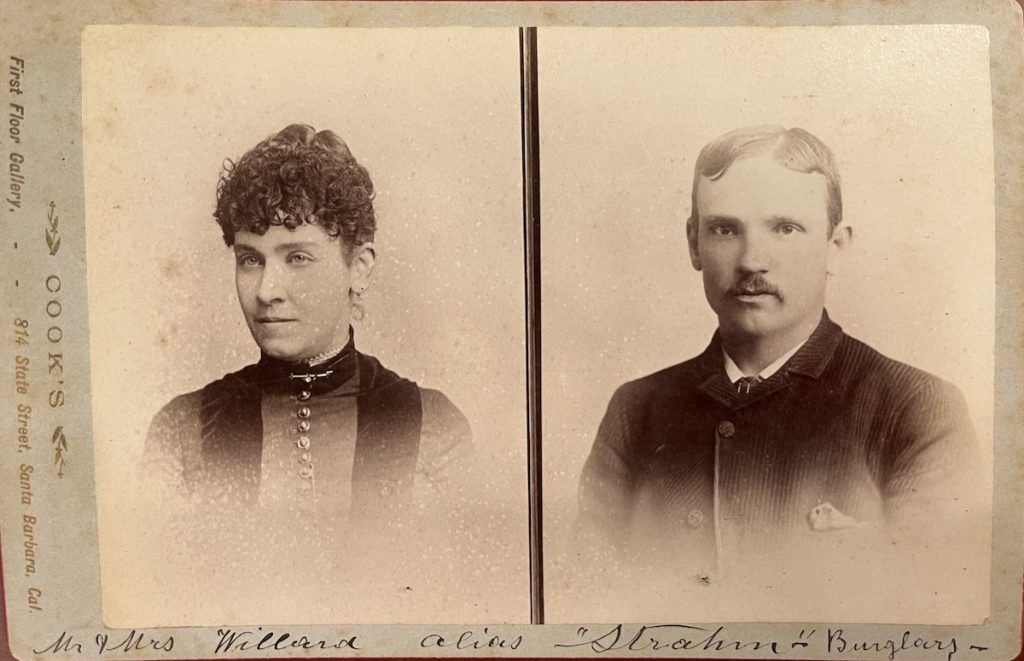

The luxury and importance of a chicken dinner cannot be underestimated. In 1889, Frank Willard, former proprietor of the Retreat Saloon (which had burned to the ground under suspicious circumstances) was arrested for being the head of a burglary ring which had been operating in Santa Barbara for months. He was known, apparently, as a maque (pimp), gambler, loafer, and opium fiend, and was caught red handed with two crates and several boxes of other people’s belongings plus a complete set of burglar’s skeleton keys. He was subsequently convicted and sentenced to 25 years in Folsom prison. Upon the eve of his departure from Santa Barbara, he and his wife May, also an opium addict who was rumored to have worked in a house of “ill fame,” were allowed to be together for a last chicken supper.

Chicken Theft

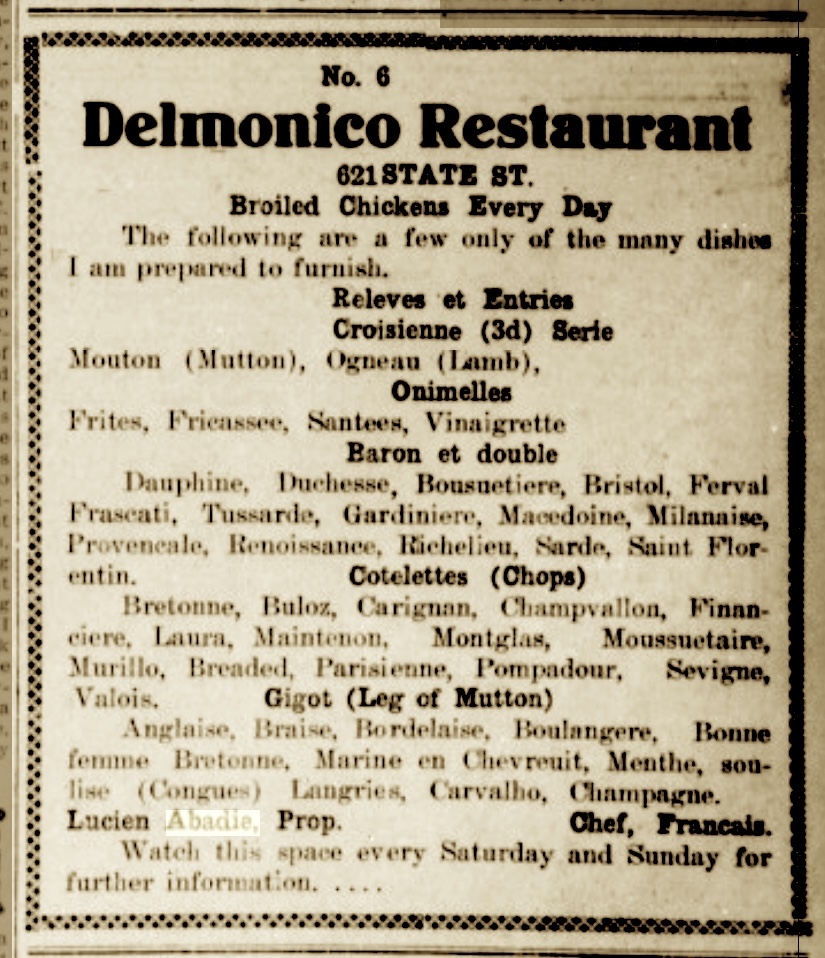

As Sunday chicken dinners grew in popularity, chickens became a hot commodity. In 1909, Lucien Abadie, chef first Grand Prix Culinary Art, Paris Exposition 1900, arrived in Santa Barbara and opened a restaurant at 621 State Street, which he named Delmonico’s. Lucien had high aspirations for his restaurant, and advertised a menu that would make a gourmand’s mouth water. Unfortunately, gourmands were few and far between in Santa Barbara. To make matters worse, he was the victim of a crime soon after he opened.

In November, Gin Buck, who had been working at the restaurant for several weeks, offered to sell Abadie a dozen chickens. They looked plump and well cared for and with Sunday’s fricassee of chicken coming up, Abadie paid Gin the very reasonable asking price. When he later looked at the chickens more closely, however, he was stuck by how similar they looked to the chickens he had at his residence on West Haley Street.

With grave suspicion in his mind, Abadie rushed home to count his chickens and, sure enough, a dozen were missing. Not only had Lucien purchased stolen chickens, but they had been stolen from him! Gin, meanwhile, had flown the coop on the 6:35 train to San Luis Obispo. It was months before he was caught at a fan tan game at Guadalupe.

Chicken thievery continued to be a popular profession, and in 1915 a Hope Ranch poultry farmer awoke to find the heads of nearly 100 chickens near his hen house. Apparently, there had been many reports of similar transgressions, and Sheriff Stewart was on the hunt. His investigation found that a peddler named Jim McGraw, who’d been in the area for about five weeks, was, according to the press, “responsible for the greater part of the chicken theft epidemic that was raging in the region since the advent of this wideawake dealer in feathered meat.”

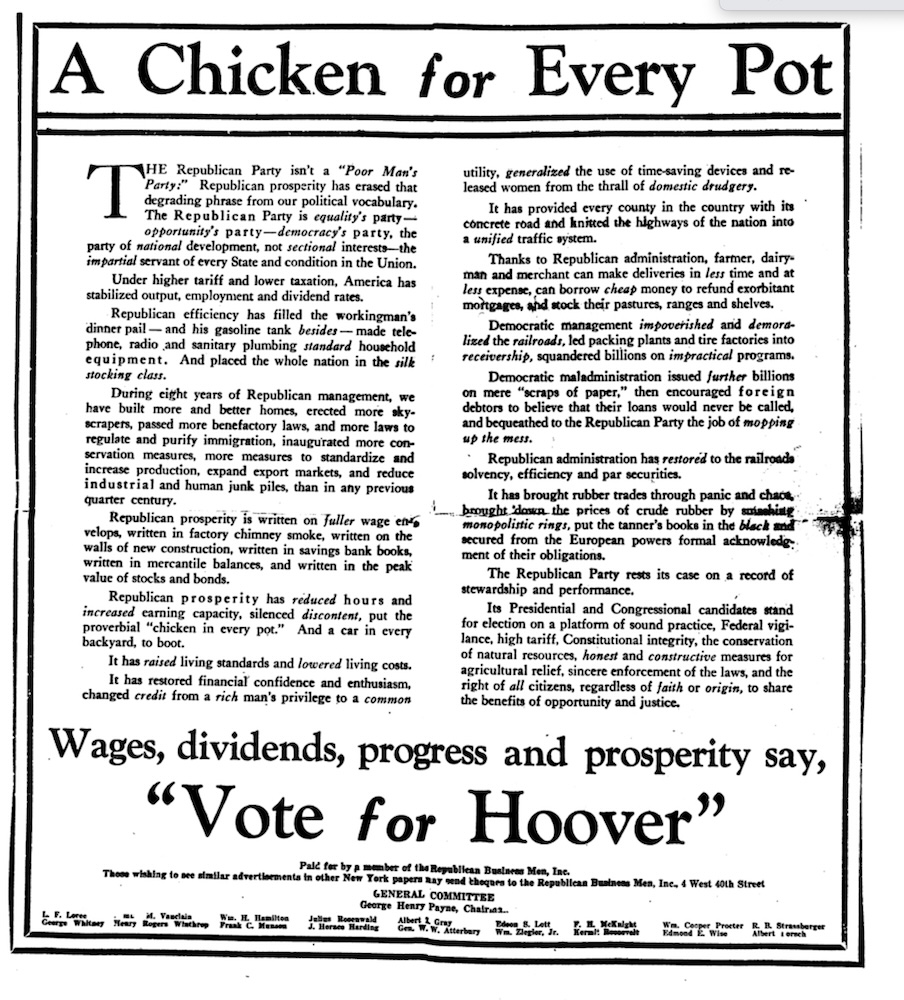

The popularity of eggs has waxed and waned over the years, especially when a 1977 government report declared the “sky was falling,” and labeled them high in cholesterol and to be avoided at all costs. Eggs were officially reprieved in 2013 when the government acknowledged that dietary cholesterol was not a factor in cholesterol health. The popularity of chicken meat, however, has continued to grow and the latest reports say that people eat over 100 pounds of chicken meat per year. Now that’s something to crow about.

Main Sources: Contemporary news reports; Forbes, “How the Chicken Got to America,” by Kristina Killgrove, 1917; Smithsonian, “How the Chicken Conquered the World,” by Jerry Adler and Andrew Louler, 2012; “The Horse, Santiago, and a Ritual Game,” by Jill D. Sweet and Karen E. Larson, undated on Jstor; “The California Slipshod Method: Poultry Farming in 19th Century California, by H.D. Miller at eccenticulinary.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.