The Channel Islands as Curse and Salvation

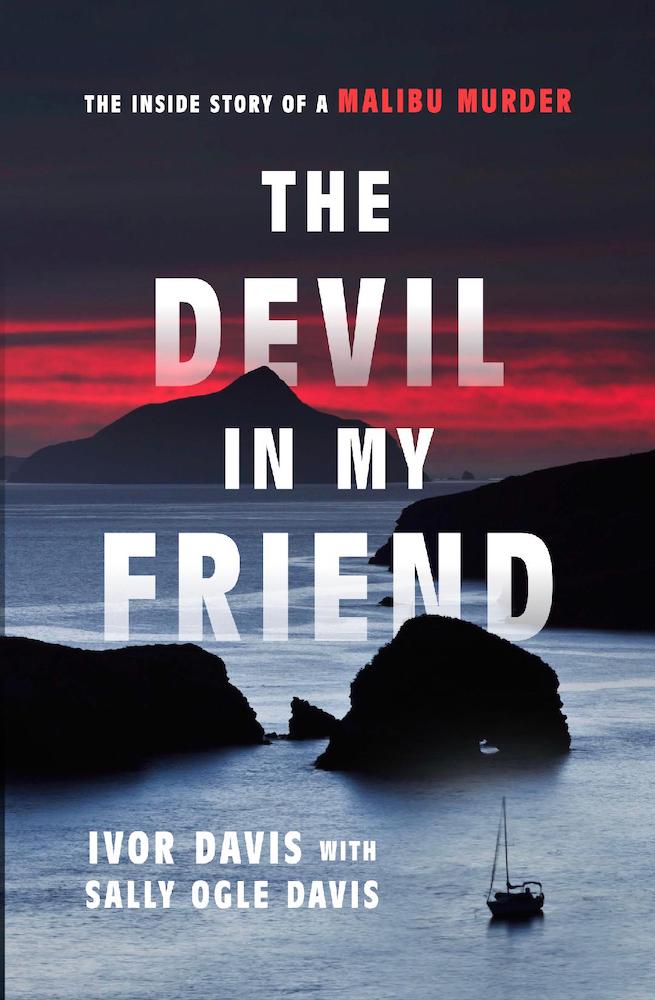

‘The Devil in My Friend’ by Ivor Davis

Malibu has been called a colony, an enclave, and several other things along an overwrought continuum that can stray into bad poetry. The very idea of Malibu can be so frankly dazzling it beggars reliable description, this macabre strip of trillion-dollar stilted waterfront huts peopled by reclusive skulking titans. Fitzgerald famously said, “the rich are different,” and it’s arguable they are nowhere more different than in Malibu. Wikimedia smugly tries to bring it down to size by calling the place “…a beach city in the Santa Monica Mountains region of Los Angeles County.” Nice try, Wiki. Kind of like calling Neil Armstrong a onetime pilot and failed husband. Malibu is storied in a way that only a self-referent American locus can be storied. It is a town, yes. But more significantly Malibu is symbol of a largesse unique to our founding economic prayer here in the States, where striving is both means and end. Summiting is the gold-plated American raison d’être, but some of the shortcuts from base camp are paved with sorrow.

Ivor Davis’ relentless The Devil in My Friend is a tightly-written, meticulously reported chronicle of, yes, a Malibu Murder – that place name and noun announced in hemoglobin red on the book’s cover. This true crime story’s hook may be its proximity to magical Malibu (the crime itself took place on the water near the Channel Islands), but Ivor Davis’ chronicle, written with Sally Ogle Davis, ultimately succeeds on the fastidiously mesmerizing nuts and bolts of its reporting, and on its calibrated willingness to color the reportage with just a hint of writerly come hither.

If you’re averse to true crime books that make you a seven-hour hostage, avoid this one. The book’s compulsively readable verve is given angular momentum by the author’s relationship with the murderer, and Davis’ initial outrage at the suspect’s arrest for what plainly looked like an accident at sea. It seems the convicted killer was the author’s friend and Malibu neighbor; a twice-married, twice widowed (widowered?) life insurance enthusiast named Fred Roehler. We may never wholly know what evil lurks in the hearts of men, but we do know that it is very often bank-account adjacent. What some people are capable of in pursuit of liquidity never ceases to amaze.

The details of the crime itself are hypnotically sloppy in a way that makes a trial attorney’s pulse quicken. The captured reader is walked inexorably to a courtroom drama absolutely rife with granular forensics, victims’ viscera being woefully intermingled in post-mortem buckets (literally), and a witness producing a skull from a grocery bag. Never mind the large orange dory propped on sawhorses a few feet from the jury. This review can’t begin to document the deep evidentiary filigree that defined the case, but it is Davis’ mastery at bringing all the byzantine detail into focus that makes this book both addictive and – in the manner of the very best true crime documents – actually edifying.

At this writing there is still a public campaign to free Fred Roehler, so arguably dense and divisive is the whirlpool of evidence related to the case. Roehler has been in jail for 42 years. These true stories of determined mayhem are almost uniformly unlikely. Just off Santa Cruz Island one afternoon, something terrible happened at the sun-drenched intersection of fiduciary desire and a dog jumping out of a rowboat. From such beige bric-a-brac can tragic malfeasance blossom like a corpse flower.

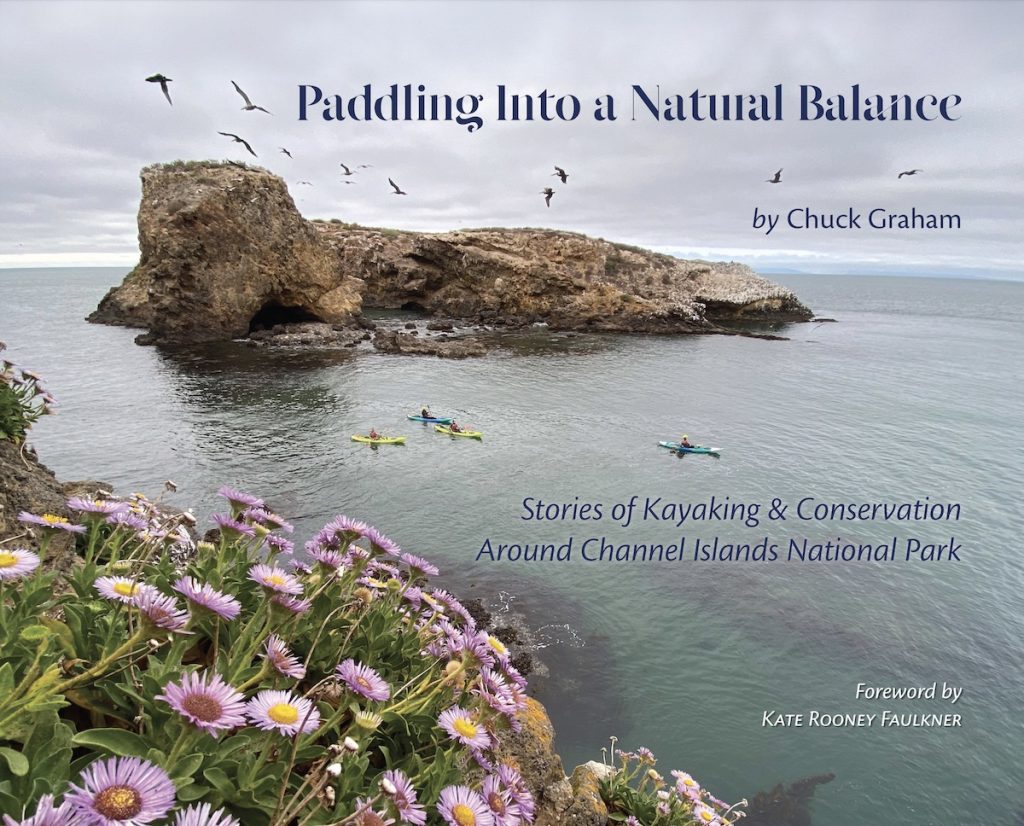

Channeling Earth: ‘Paddling Into a Natural Balance’ by Chuck Graham

Down here on the ground, the planet Mars is familiar as a bright orange dot in the morning sky before dawn. “Hey, see that? It’s Mars.” “Huh. Cool.” Then you get a look at the images sent back by the plucky Mars rover (the suitably named Perseverance), and there are mountain ranges and canyons and plains and craters. The dot unfolds into a world and the crazy juxtaposition fascinates. So it is with our Channel Islands, the neighborly archipelago parked off our coast like a familiar old pal. It rarely occurs to the casual observer that one can go ashore and walk around these things. When a skilled, impassioned, and lovesick artist (and MJ contributor) like Chuck Graham does exactly that on our behalf, the conveyed sense of amazement is very nearly Martian. Honestly.

“‘I’ve been a surfer for nearly 50 years, a beach lifeguard for 32 years. I’ve kayaked the islands for 28 years, 22 of those as a guide,” Graham tells us in the forward of his magisterial Paddling into a Natural Balance – a dizzying cornucopia of hypnotic photojournalism that surrounds and completely captures the reader. Graham is as organic a creature of his beloved Channel Islands as are the Brandt’s cormorants that nest and make their lives there, and his ease and natural sympathy with the islands’ rhythms bring you right into the magic. The author’s unadorned but loving prose wraps around a collection of proffered photos you have to see to believe.

Graham puts you right there on the largely unimaginable islands – part of the national park system since 1980 – where you find yourself a goggle-eyed wanderer. Were the scenery not contained in this moveable feast of a book, you would be in some danger of waking off a cliff with an idiot grin plastered onto your yap. Whatever your feelings about “nature photography” you haven’t seen it done the Chuck Graham way. These are stupendous visuals, stupendously captured. His images have the effect of somehow compounding the mystery of the islands, so crazy is the glory out there.

There is a photo on page 36 of Graham’s book, taken on the “North Side of Point Bennett,” that will renew your faith in… well, you name it. Graham’s images are startling in their beauty, and in the wordless storytelling laid bare in their composition. By his own description, he takes painstaking care – often in the truest “hours of stillness” tradition of our most celebrated nature photographers – to capture and present us those moments that speak indescribable volumes.

Graham’s accompanying text throughout is a plainspoken first-person narrative that charms in the author’s tenor of frank astonishment at what he sees and records – an astonishment undiminished by his decades of island visitation as guide, explorer, and monastic pilgrim. This book is part walking tour of an island chain as varied and extraordinary as any in the world, part engrossing conservation record, and part unguarded love story. Yeah, you’re going to fall in love with the islands. In this context Graham is the Cyrano whose expressionist art seals the deal. The whole project is offered in a spirit of variously playful and prayerful reverence, by a guy whose own lifelong mission remains singular; to lift the veil on natural wonder itself.

Chuck Graham simply and movingly dedicates Paddling Into a Natural Balance to his father, quietly introducing the whole stunning project with a telling grace note. Here is a parent who saw what his child was destined to be and held the door for him. Graham Sr.’s blessing is a gift to us all.

You must be logged in to post a comment.