Grass is Greener (Than Previously Reported) on Both Sides

In 1936 they released the notorious Reefer Madness, a social horror movie lightly dressed up as a PSA. Reefer Madness lives up to its nominal hypothesis, portraying the effects of cannabis in a terrifying Jekyll-and-Hyde framework that sees gee-whiz youngsters turned into shifty-eyed, maniacally giggling creeps after a single puff. Marijuana was the sinister trojan horse that would bring society low. Fast forward 90 years and the most frightening thing about cannabis is how awful it smells. And that’s without striking a match.

A great civil skirmish has been afoot in our beloved Carpinteria – one of the few coastal California towns to retain its 24 karat Golden State charm. The cause of the fallout? The ungodly stink of cultivated dope. The warring armies – on the one side, odor producers CARP Growers (Cannabis Association for Responsible Growers) and on the other side, odor plaintiff Santa Barbara Coalition for Responsible Cannabis – both self-identify as Responsible; and in fact, the relationship has indeed evolved despite recent reports to the contrary. The whole dustup began somewhat confusingly.

Jules Nau is VP of the Santa Barbara Coalition for Responsible Cannabis. “I moved to Carpinteria and I’d just remodeled my home. Suddenly one morning I smelled skunk all over the house, like something died in the basement.” There was no basement, which was troubling. Nau started chasing the critter anyway. “The gentleman came over and installed a trap, and we waited, and waited. Nothing. At one point he said ‘…listen, what time of day are you smelling this stuff?’ I’m like, ‘Man, it’s only in the morning and I cannot get rid of it. That skunk is persistent!’ And he says, ‘You don’t have a skunk problem. You have a skunk problem.’”

To Envinity and Beyond

Legalized cannabis had arrived like a white knight to rescue Carpinteria Valley’s flower growers from years of increasing fiduciary anemia brought on by offshore competition. The cannabis news was so good for the embattled generational farming families in the area, there almost had to be a caveat. No one guessed it would be a free-floating, jaw-clamping stench.

Once the noxious event was identified, all heck broke loose. Litigation sprouted like a field of Hairy Bittercress. The community drew battle lines. Right around then a Dutch outfit called Envinity entered the picture. Their patented CFS-3000 Scrubber – an ingenious amalgam of cleanroom-quality microfilters, carbon, UV, pathogen-killing ionization, and diagnostic data-streaming – would measurably rid the air of 84% of the cannabis whuff. Envinity just needed a partner willing to double down with them and see the exhaustive vetting process through. “That was Philip Greene and Ever-Bloom,” says Simon van der Burg, Envinity’s co-founder and managing director. Greene would ultimately buy and install about $2 million worth of Envinity’s scrubbers, warehousing extras to later gently foist on his reluctant colleagues. Envinity’s solution was determined to be the solution to the odor calamity and much more. It didn’t come easy.

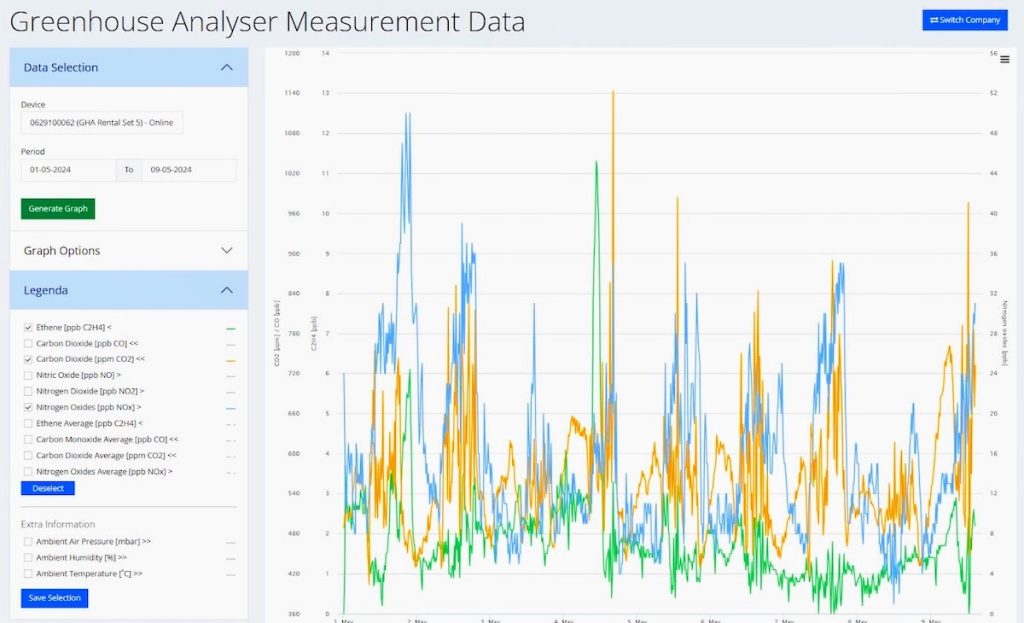

The testing and reporting and collating, van der Burg’s repeat visits to Carpinteria, the bi-weekly scrums, the start-again stop-again data-parsing; it was a harrowing, laborious, and expensive process they were determined to get right. Environmental Monitoring Systems workers would be flown in from Holland and boarded at Envinity’s expense to validate and collate the output, and U.S. environmental consulting and contracting firm SCS would exactingly interpret the data.

Two lengthy reports would be issued, rife with the eyebrow-furrowing graphs, charts, and hieroglyphs that make professional data junkies leap into the air and high-five in slow motion. Conclusions? Given adequate spatial density as demonstrated by this study, the CFS-3000 scrubbers are capable of reducing odor emissions to a level that would result in no perceivable cannabis odors downwind from the subject facility.

Despite the glowing reports, most of the growers took a half-step back. Envinity’s CFS-3000 Scrubbers cost $22,000 each and the flow technology requires 10 of them per acre to reach odor abatement compliance. Van der Burg smiles wearily. “The growers are now saying, ‘We have no money.’”

Envinity’s managing director is not unsympathetic. Van der Burg knows farms, farmers, the economies of ag – and business investment. Tiny Holland, population 18 million, is smaller than West Virginia – and the world’s second largest exporter of agricultural products after the United States. The CFS-3000 is more than an odor-eater. It performs a litany of milieu-polishing functions that better the growing environment and sharpen productivity over time. Buy the result of Envinity’s $800,000 R&D, and you’re buying Dutch ingenuity, contractual support, and granular analysis of your greenhouse’s data as it streams through their sensors. Holland, remember? The CFS-3000 is an agriculture optimizer. Van der Burg expects the growers will come around. But when?

“With these scrubbers you make the community happy and you have a return on your investment within two years. In the Netherlands the ROI on tomatoes is five or six years, but those crops are buying the scrubbers anyway. That tells you something.”

Lion, Lamb, and Litigation

The two guys in this room are clearly pals. CARP Growers and the Santa Barbara Coalition for Responsible Cannabis have reached a good-faith rapprochement of the sort that attorneys call a “bummer.” Philip Greene of Ever-Bloom is all smiles. “The initial filing made it clear the Coalition were not out for monetary gain or to be ‘made whole.’ The goal was, and remains, to drive improvement on odor control. And about two months before the lawsuit was filed, we actually were in conversation with the manufacturer. That ended up being Envinity.” He nods genially at Jules Nau across the conference table. “The coalition sometimes likes to say that the lawsuits jump-started all this. But we’d already come up with the plan before the litigation. The timing was nice.”

Greene, a Tom Hanks lookalike, had invited me up to Ever-Bloom’s operation on Foothill Road to see for myself the Lion lying down with the Lamb. Still, scattered reports suggest agreements, informal and otherwise, have “broken down.” Coalition VP Jules Nau waves the idea away.

“On behalf of the coalition, nothing has broken down. We talk to each other on a regular basis – on the progress of odor control and being good stewards of this wonderful place.” Nau leans forward and seems to be winding up. “The main reason the coalition exists at all is because there was a failure at the county supervisory level. If they’d done right by Carpinteria and her residents from the outset, from licensing to taxation to odor control, none of this would have happened.”

“2021 was much more profitable than it is now,” Greene says of the growers’ can-kicking that is now coming into play. “So I think it was easier for a lot of growers to say, ‘Yeah, whatever comes up, we can afford it.’ Today it’s a harder business decision, but it’s still a business decision.” When the litigation came down, things were a bit more copacetic than has been reported. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh God, what do we do? We’re getting sued!’ The coalition,” Greene says, “was like, ‘Okay, let’s see how this bears out.’ Just keep us updated.” At this writing, the parties are looking for a way to take the results of the studies and move forward. “The litigation went on hold until we could get through testing, prove that our solution worked,” Greene says. “It does.” For his part, Nau wants to correct the notion that the coalition is simply anti-cannabis.

“We’re not about shutting down cannabis or making business impossible,” Nau says. His next line is delivered like an amiable shrug. “We’re just about them taking responsibility for their grows, making the right decisions for the community. We both love it here.” Nau starts talking about some foolhardy county spending and Ever-Bloom’s financial guru, Whitney, gently but sardonically corrects him. Nau grins and there is congenial laughter. The kumbaya momentarily stills the room. Greene breaks the spell.

“You wanna see a scrubber?”

We walk across an expanse of forklift and concrete to an enormous, verdant space, science-fictional. Cannabis stretches away in orderly rows for what looks like miles. There is no smell whatsoever, which I don’t even realize till Nau points it out. Envinity scrubbers are neatly bolted at intervals to the greenhouse framework in businesslike symmetry. Cheech and Chong would not like this.

“We used to have Gerber daisies, so cut flowers,” Greene says, looking across the expanse. “They’re an annual. They stayed in the pots and we would just cut the stems and they would regrow. So cannabis is a little more labor intensive.” I look over at Nau and he’s staring out at all the chlorophyll, then meets my eye and grins like a neighbor. Greene is watching a guy in the middle-distance maneuver a wheelbarrow. “Most of the workforce that you see out here, they’ve been here for 40 years. Their kids have grown up with the person who built this greenhouse. It’s farming. It’s generational.” He looks at Jules and me. “I grew up in a super small town in Washington,” Greene says. “It’s the same every day. Getting up and doing the things you need to do to make it.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.