How Conflicts Get Resolved

What’s remarkable about human conflicts – even very nasty ones – is that they usually do get settled, one way or another. Here are some ways this can happen:

By overwhelming force (war).

By negotiation and compromise.

By some kind of payment or reparations.

By legal process, i.e., “going to court.”

By persuasion.

By agreed-upon arbitration.

By intervention on the part of others not involved.

By something bigger, such as a natural disaster, becoming more important than the dispute.

By time – and the disputants simply dying off, or outliving the issue.

And what about “Love,” as taught by many great religious leaders?

Unfortunately some of the longest, most bitter conflicts have been between close neighbors. Between 1870 and 1940, France and Germany, who are mostly separated only by the Rhine River, fought three devastating wars. Somehow, it took all those “lessons” to teach these two largest powers of Western Europe to organize, with all the others, economically and militarily, to prevent any more fighting of each other, and protect them all from what are seen as outside dangers.

But these wars can leave lasting bitterness. As one illustration, after the 1870 conflict, the City of Strasbourg which had been a municipality of France, became officially part of Germany. At that time, there had for years been in Paris a monument representing Strasbourg as part of Eastern France. After the great defeat and loss, that monument was not removed, but was kept permanently draped in black – until 1919, when Strasbourg went back to France after Germany’s defeat in World War I. This was part of the so-called Versailles settlement which, however, was so unfavorable to the Germans that it became one of their grievances which Hitler exploited, and led to the rise of the Nazis.

In my own lifetime I have seen enemies becoming close friends. As a child growing up in World War II, I was taught only hatred towards the Germans and Japanese. But we, the victors, did not deal harshly with the vanquished. Apart from prosecuting a few “war criminals,” we mainly tried to help them recover. This also induced them to copy our own democratic institutions.

Although there have continued to be relatively small-scale conflicts in various parts of the world, confined to small areas, there has not since 1945 been anything like a Third World War. One factor in this situation is the way the last one ended – with the use of a new weapon so terrible and uncontrollable in its consequences that even potential users have shrunk back in horror.

This brought about a new term for a new type of conflict-avoidance, aptly referred to by the acronym “M.A.D.” standing for “Mutually Assured Destruction.” Under this contemplated scenario, any use by one side of the “Ultimate Weapon” would automatically trigger use of the same weapon by the other side. Being automatic meant that a point might be reached at which, even if the leaders realized that a mistake had been made, neither side could bring back, or even disarm, the missile(s) it had launched.

One might hardly expect such a situation to be appropriate material for comedy, but a movie appeared in 1964 which might be called hilariously frightening. The title was Dr. Strangelove. And central to the plot is the idea that someone with power to launch “The Bomb” might go insane.

Only two years earlier, the actual “Cuban Missile Crisis” had occurred, in which the two nuclear-armed super-powers, the U.S. and the Soviet Union, came close to a confrontation over the installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba. That genuine conflict was settled by one side (U.S. President Kennedy) taking a strong threatening stand, and the other side (Russian leader Khrushchev) backing down.

In recent centuries, various attempts have been made, as in the 1907 Hague Convention, to bring warfare under some kind of legal framework. And even today we hear the term “Laws of War,” although that whole concept hardly takes account of what we call “terrorism.” But there are well-intentioned groups dedicated to making peace. One is called “Earthstewards,” which I myself joined on a journey to the Middle East, in an attempt to ease tensions between Israelis and Palestinians – speaking with people on both sides, and actually visiting and staying in their homes. A worthy effort, but, as you know, hardly successful.

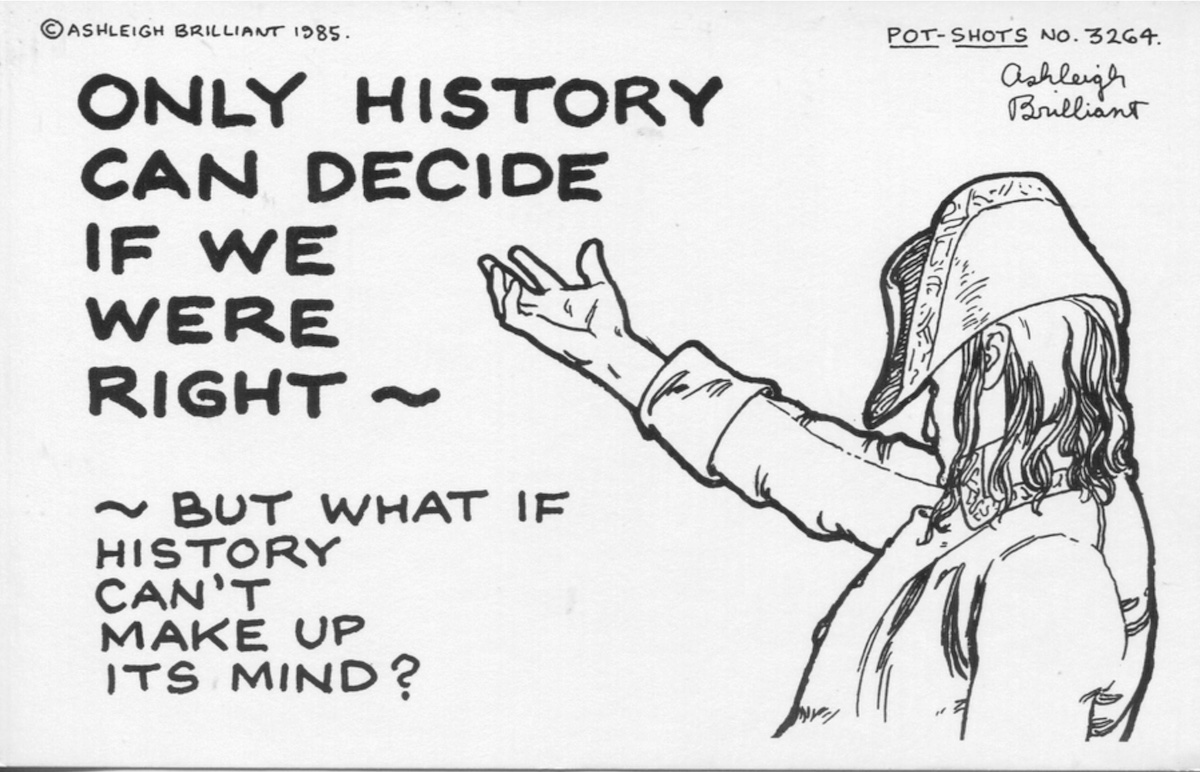

One of my epigrams sums up the problem this way:

“Isn’t there some way we can settle our dispute, without resorting to agreement?”