Getting Settled

One piece of advice I’ve given myself (after some unhappy experiences) is this: “Try to avoid situations in which all you have is a good legal case.” Of course, it’s desirable to have the Law on your side – but it’s even better to be able to negotiate an “out of court settlement,” sometimes through the process called Arbitration, which doesn’t need lawyers, courts, or judges. This usually requires some flexibility from all parties. But the fact that it’s invariably faster and cheaper is a powerful inducement.

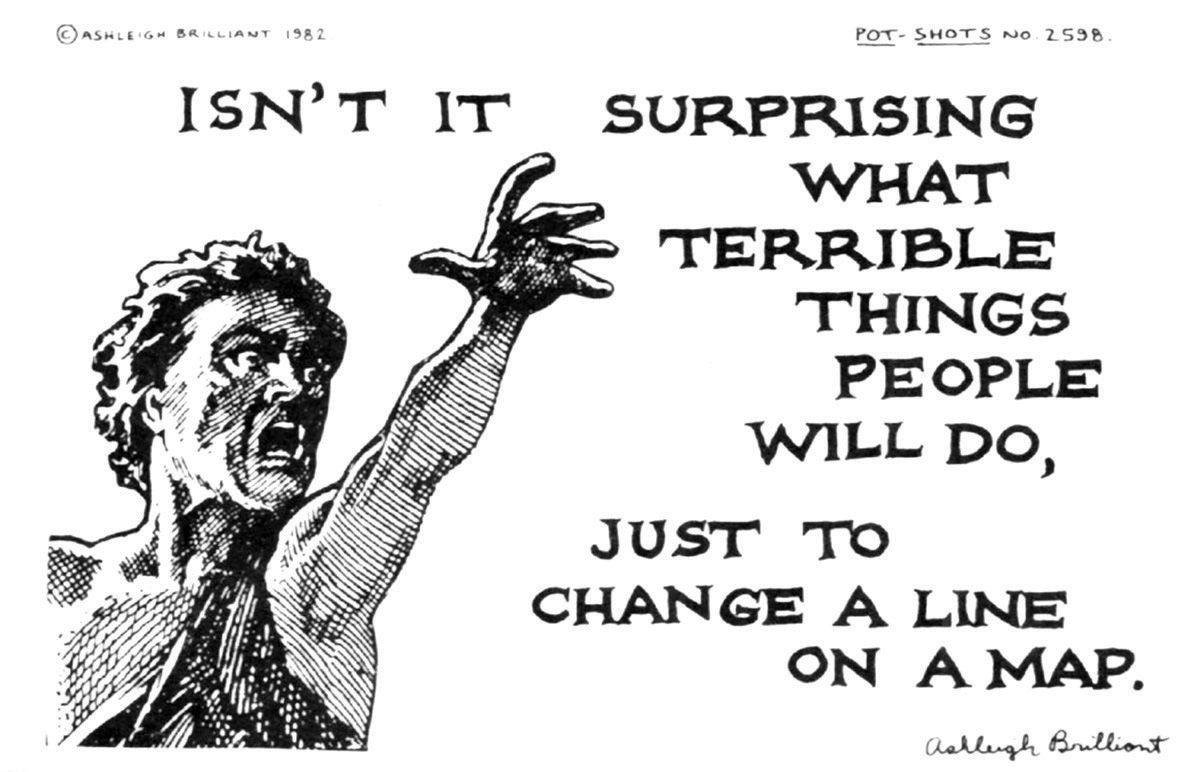

Nevertheless, throughout human history, there have been disputes which could only be resolved either by physical conflict or by resort to some kind of judicial proceeding. No doubt the earliest of such needs had to do with the ownership of land. And this brings us to the other central idea of settling, which is, of course, to stop moving, and remain in one fixed locality. A frontier ceases to exist when everybody moving towards it has become a settler and established a home.

America spread westward from the East Coast where, at first, there was only a thin string of mostly English settlements. A key historical moment came in 1890, when the U.S. Census Bureau announced that it could no longer draw a clear line between settled and unsettled areas. In effect, there was no more frontier. This prompted a historian named Frederick Jackson Turner to begin theorizing about “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” He espoused some controversial ideas about how the existence of a frontier had fostered democracy and been instrumental in establishing a distinctive American character.

One remarkable element in that whole process was the concept of what was called “homesteading.” This was a somewhat rare instance in which the Federal Government acted as a benevolent landowner, distributing acreage to private citizens. Of course, there were conditions. You had to be a Citizen and head of a family. You must live on the land, and “improve” it, which usually meant farming it. This all started, officially, with the Homestead Act of 1862, signed by President Lincoln – and was considered to be one way of strengthening the Union during the Civil War. But, together with subsequent Acts, it remained in force long after that War was over.

One person who took advantage of that Act was a doctor named Brewster M. Higley, who moved from Indiana to western Kansas in 1871 in order to take up a homestead. It was he who wrote the piece of verse which, set to music, became a celebration of this entire westward movement. The song’s first title was “My Western Home,” but we know it today as “Home on The Range.” And the people of Kansas are so fond of it that in 1947 they made it their official State Song.

During the “Hippie Era,” in San Francisco, I wrote my own version, which includes:

Home, home in the trees,

Where all people can do as they please,

Where seldom is heard a Middle-class word – and Reality’s just a disease.

Another aspect of settling has to do with crowd control, or even with classroom control from a teacher’s perspective, especially among younger students. As we all know, when no regular teacher is present to keep order – as I personally learned from experience on both sides of the front desk – and a substitute teacher appears in the regular teacher’s stead, a class can become very disorderly. What begins as a hubbub may develop into an uproar. The problem then is just to have things get quiet. I can remember some of my own teachers saying things like “Now stop talking, and settle down!”

Sometimes we talk about settling up, which usually connotes paying a debt. Since our whole economy is based on credit, I have always thought it remarkable that one of the first prayers children are taught – and sometimes the only one – specifically asks God to “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.” But Shakespeare in Hamlet has wise old Polonius advising his son (who is about to depart for foreign lands) that he should “Neither a borrower nor a lender be.”

In my own life, settling has mostly involved going somewhere with someone else who wanted to live there. Indeed, the only place of residence I can recall which I myself chose was a town which I celebrated in one of my epigrams:

There may be no Heaven anywhere –

But somewhere there is a San Francisco.