School Scars

From the ages 13 to 18, I went to school in Hendon, a London suburb. It was just after World War II, and in the field behind the school were several surface air-raid shelters; recent wartime relics which were now being used for storage. They were not locked. Once, when during a holiday I had been up all night hitchhiking with a friend to a different part of the country, we got back only just in time for school. I was too tired even to attend class, so I went into one of those structures, lay down on a bench, and fell asleep.

What seems remarkable to me, remembering this episode, is how unusual it all was – the hitchhiking, the air-raid shelters – and the school itself.

As to the hitchhiking: this had been my very first trip – of many I made while still in my teens – all over Europe, in the Middle East, and across America. Most people in those days – and probably even more today – considered hitchhiking a risky business. But I’m glad to say that, in all my hundreds of rides, I never once had a bad experience. On the contrary, this seemed to be a good way of meeting good people. And I learned that the best way of thanking them for giving me a ride was to get them talking about their own lives and interests.

But another part of this memory which seems of particular significance were the air-raid shelters which, at that time, were still very common; sometimes even built on the paved roadways.

With my family I had been, for the seven years of war, safely “over here”; first in Canada, then in the U.S. Meanwhile, “over there,” the British people went through a terrible time. Although no invasion ever took place, there were years of raids by bombers and, towards the end of the war, by pilotless “buzz-bombs” (which could sometimes be shot down), and “rocket bombs” against which there was no defense. (They were so fast that the noise of their coming was heard only after they struck.)

While we had been spared all of that, the evidence of it, in the form of ruined buildings, or just gaps where houses and buildings had once been, were everywhere to be seen.

And there were the horrifying first-person accounts, from our relatives and friends, of what it had been like, night after night, when the bombs came down. This was all part of the so-called “Battle of Britain,” in which Hitler, like Napoleon – having conquered the rest of Europe – attempted to eliminate his last Western enemy before turning East, against Russia.

And that memory of the shelter incident, also made me think of the school itself. One unusual thing about it was that it was “co-educational,” in an era when most British schools were still exclusively either for boys or for girls. But separation persisted to some extent. E.g. in Assembly, we stayed on opposite sides of the hall.

Another striking feature was the personality of our Headmaster, Mr. E.W. Maynard Potts. He was tall, with a ringing voice and piercing eyes. He always wore a black academic gown. Most of us were to some extent afraid of him. In those days, “corporal punishment” in schools was still permitted, and it was the “Head” who administered it – once upon me in his office, with a cane, on my buttocks, bending over his desk. That was for having dared to criticize my English teacher’s methods on an examination paper. My parents had to go and beg him not to expel me.

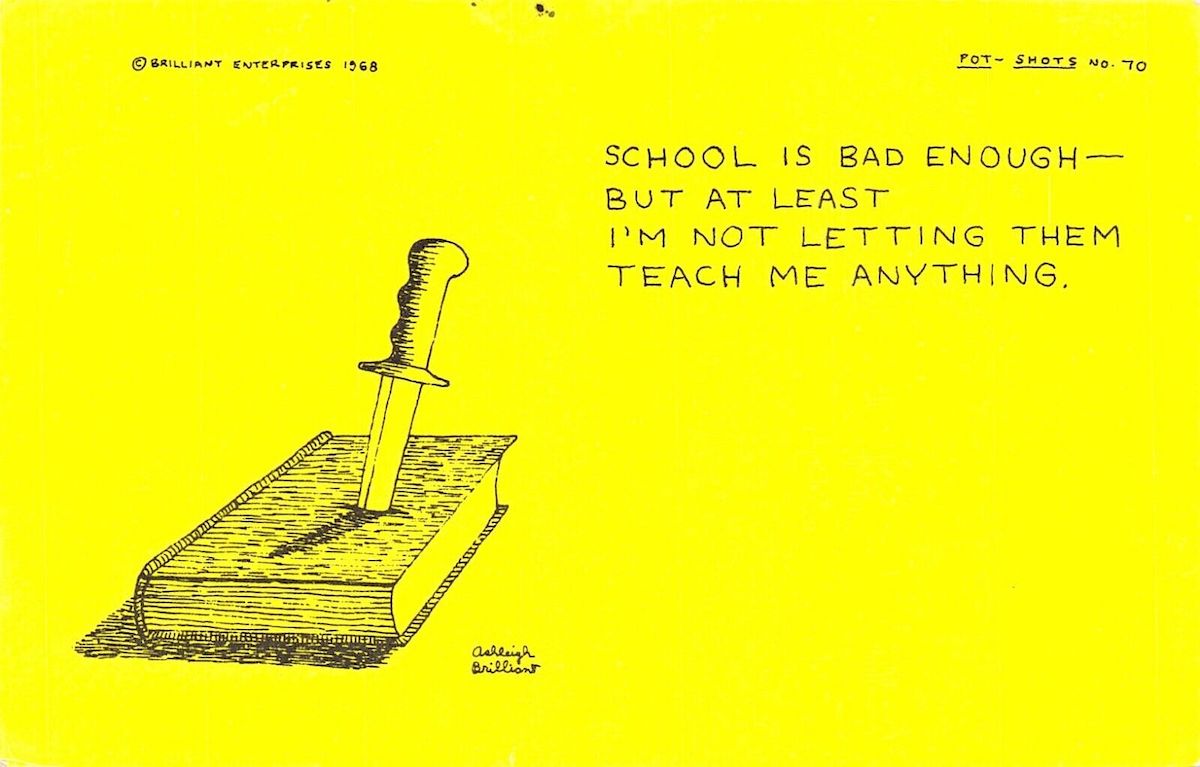

Remarkably, this man kept in touch with me for years after I graduated, writing me sometimes long personal letters. At one point, after I made a commercial success in America of selling my own epigrams, he wanted to become my British business agent!

Another aspect of the school, during my time there, was that about one third of the students were Jewish. This reflected a fairly recent change in the nearby communities. Since Christian prayers were said in the regular Assembly, we had our own separate “Jewish Assembly,” meeting in a classroom.

One big event of the school year had been an annual Christmas Carol Festival. But with the difference now in the school population, it was decided to cancel this event. This brought a great outcry from all the non-Jewish families. Mr. Potts’ job may have been in jeopardy. At any rate, the cancellation was cancelled.