Please Attract Me

Much of this system called Nature is apparently based on attraction and repulsion. The repulsion serves to protect – and to keep at least certain members of a species intact – until they have time to reproduce. The attraction is also part of that reproduction process. Most plants can’t physically get together, so some have developed methods of using insects to carry pollen between them.

But first they have to attract the insects – which accounts for the bright colors, elegant structure, and sexy scents characteristic of many different flowers (in case you thought it was all just to please us).

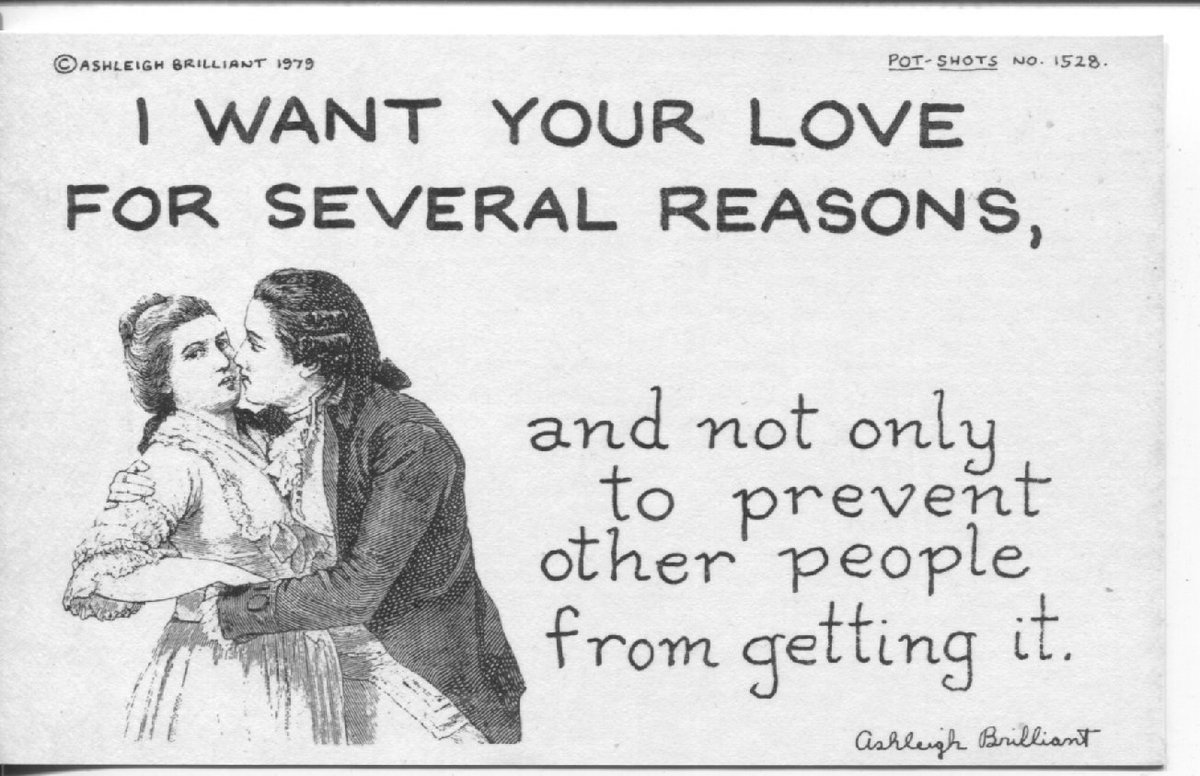

And that brings us to people, who are also subject to this strange law. In terms of repulsion, all we have left us by evolution are some not very menacing teeth and nails, plus whatever vocal and physical – mainly facial – expressions we can make to appear threatening. To attract potential mates, so little remains of our original shapes and smells that civilization, culture, and fashion have to keep coming up with new and different ways of bringing about the same old crude coupling, which basically never changes.

But attraction extends all around us, in the forms of what we call magnetism and gravity. Some invisible force pulls some things towards some other things. And, to make it all even more confusing, there are also invisible forces of repulsion (as if bad smells, poisonous surfaces, thorns and prickles, weren’t enough). And hunters still have to use deceptive devices to attract their prey, so that they can kill it.

Among people, however, there is also an amazing variety of preferences as to what is attractive. In some places fatness is a measure of beauty, while in other places, as you well know, it usually just means being overweight. Similar standards also apply to hairiness and body odor. And, when it comes specifically to sexual features, males and females have their own differing prejudices with regard to what does or does not attract potential mates. And it is not only a matter of visible, or even tangible, characteristics, but can extend into such realms as how a person talks or moves. Indeed, thanks to modern technology, what we used to call courtship can now take place purely by voice and camera image over great distances. One advance, which I have long hoped to live to see, if not personally to take advantage of, will be the development of “tele-touching,” by which all kinds of physical feelings, from hugs to orgasms, will be transmissible electronically.

Meanwhile, we can marvel at the way a moth is attracted to a flame – or, for that matter, the way many different insects are attracted to many different kinds of lights. If this is somehow part of a benevolent universal plan, it really doesn’t make much sense. Neither the moth nor the flame derives any benefit from their relationship. The only ones who get anything out of it are the predators who specialize in hunting their prey in brightly lit areas. In the case of the moths, their navigation systems are based on light from the Sun or the Moon, so that other lights, such as a candle, are simply confusing.

And what attracts bears to honey? Actually, it has nothing to do with what attracts us, which is, of course, the sweetness. It’s the bees themselves that bears are interested in eating, together with other contents of their hives, especially the larvae, i.e. the baby bees.

But we know better. And we know that people in general are so fond of sugar that whole economies have been based on it, and wars fought over it. Companies based on sweetness, like C&H (California and Hawaii) in America, and Tate & Lyle in Britain have made their stockholders rich and powerful. This, of course, is not a recent phenomenon. Not many centuries ago. Molasses was as important an element in international commerce as the slave trade. Various colonies in the Caribbean were known as the “Sugar Islands” and, on that account, were considered more important than other islands available for settlement. One sugar island was Nevis, the original home of one of America’s founding fathers, Alexander Hamilton.

But attraction of the sexual kind can only too often lead to tragedy, as depicted so compellingly in Shakespeare’s drama of Romeo and Juliet. Still, we should perhaps be glad not to belong to a species in which the courtship process regularly involves one partner eating the other’s head.