Cut It Out

One of the most famous of all historical events was the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. The killers were a group of men whom Caesar had considered his friends and supporters. The leader of this conspiracy, whose name was Brutus, is said to have been the last to deliver the fatal blow. And we are told that Caesar, recognizing him, uttered as his final shocked words, “Et tu, Brute” (“You too, Brutus!”) This event has been further immortalized by Shakespeare’s drama, Julius Caesar, of which probably the best remembered scene – apart from the murder itself – is that which depicts Marc Antony, a friend of Caesar who had not been part of the conspiracy, speaking at his funeral in the Roman Forum. One of the best-known lines in that speech comes when Antony displays Caesar’s bloody toga and points to the hole supposedly made by the knife of Brutus – and comments: “This was the most unkindest cut of all.”

The questionable grammar of that statement is something we have to let Shakespeare get away with – for several reasons: (1) Grammatical rules do often change over time. (2) In this case, the change made the words conform to the rhythmic pattern called “iambic pentameter. (3) “most unkindest” is a poetic way of emphasizing the extreme treachery of Brutus’ betrayal (4) and, after all, this was Shakespeare.

Happily, there are today many instances of flesh-cutting which are more kind than unkind. There is, of course, legitimate surgery, whose applications may range from removing the infected tissue of a small wound all the way up (or down) to the amputation of an entire limb. This sort of medical treatment probably began on or near battlefields. In such settings, there came to be in attendance men known as “surgeons,” who regularly carried small sharp instruments, and who doubled (between battles) as “barbers” (from the Latin word for “beard.”) And that is why, even today, many barbershops proclaim their presence with some kind of red-and-white striped pole, the stripes originally representing blood and bandages.

Unhappily, the cutting of living flesh usually involves much pain – the development of anesthesia thus generally considered to be one of the greatest advances in the history of Medicine. But it did not happen all at once. The most significant modern chapter began with the discovery, in 1845, that the gas technically called Nitrous Oxide, but commonly known as “Laughing Gas,” could, under controlled conditions, be used by doctors and dentists to render the patient insensitive to pain for long enough to permit performance of what would otherwise be a painful procedure. The credit for this boon to mankind properly belongs to an American dentist, of Hartford, Connecticut, named Horace Wells.

We still sometimes refer to being operated on as going “under the knife” although the cutting instrument most commonly used is more likely to be what is called a “scalpel.” But these too have changed greatly, and the scalpel today is usually some kind of handle with a small disposable blade. All this is to say nothing of new techniques, such as Lasers, which, instead of any kind of tangible tools, employ concentrated beams of light to do the cutting.

Of course, some of the world’s most important cuts have been not through flesh, but through land. The Panama Canal saved sailing all the way around South America; and the Suez Canal did the same for Africa. (I have done both trips by both routes and, if you enjoy having a variety of weathers, I can recommend each of these travel experiences.)

One of the most famous “cutting” stories explains what was originally meant by “cutting the Gordian knot” – an expression we now use to mean “solving the problem with a swift and perhaps unorthodox action.” Going back two millennia, this stems from a legend concerning Alexander the Great, who is said to have been confronted by a knot associated with a king called Gordius. The knot was so complex that, in a then-hallowed tradition, whoever untied it would become the ruler of all Asia. Instead of trying to unravel it, Alexander simply took his sharp sword and cut through it. – And he did indeed, in his few remaining years, conquer and rule most of what was then known as Asia.

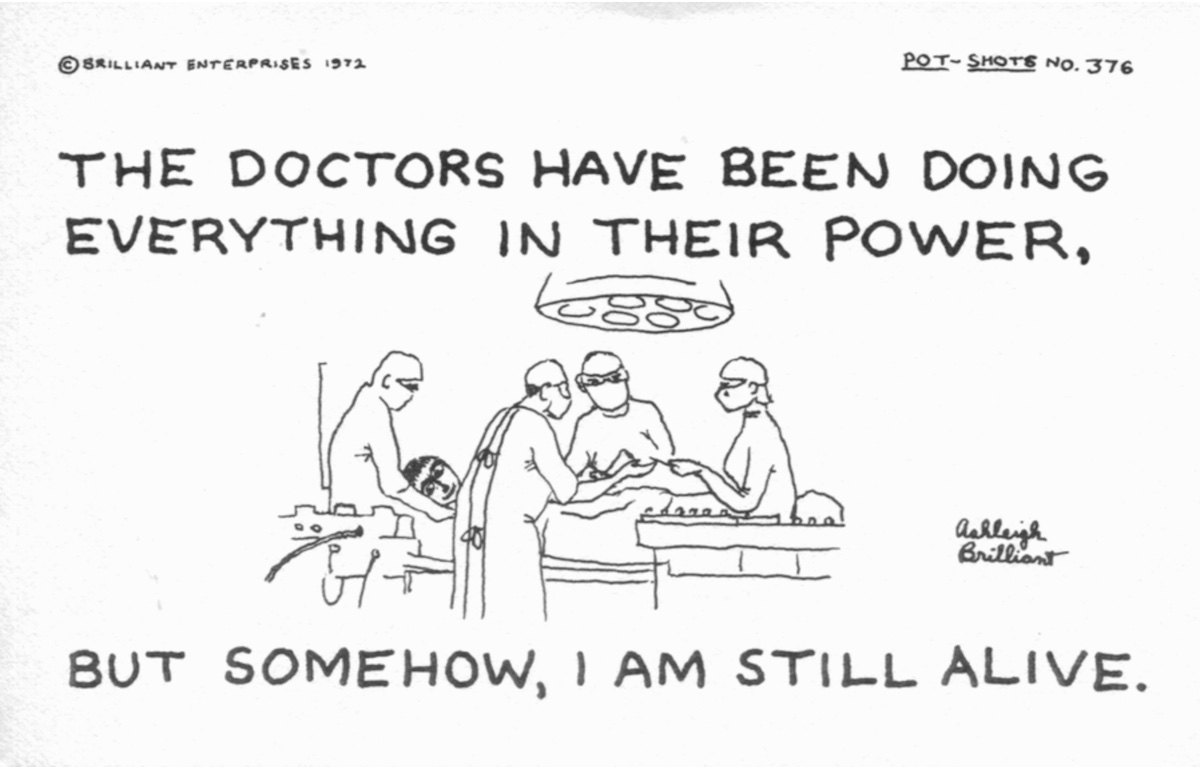

Finally, if I may follow Alexander with one of my own Great Thoughts on this subject:

“My dream is to cut all ties

with Civilization,

but still be on the Internet.”