The Venerable Covarrubias Adobe

In July 1909, much to the alarm of the Santa Barbara populace, the Morning Press announced that the venerable Covarrubias Adobe was to be razed and replaced by a modern apartment building. Without notice, Nicolas Covarrubias had sold it out from under his aging siblings, Camillo and Amelia. The first they heard of the sale of their childhood home was when they were handed an order of eviction from the new owner, Thomas Adams, a Santa Maria banker.

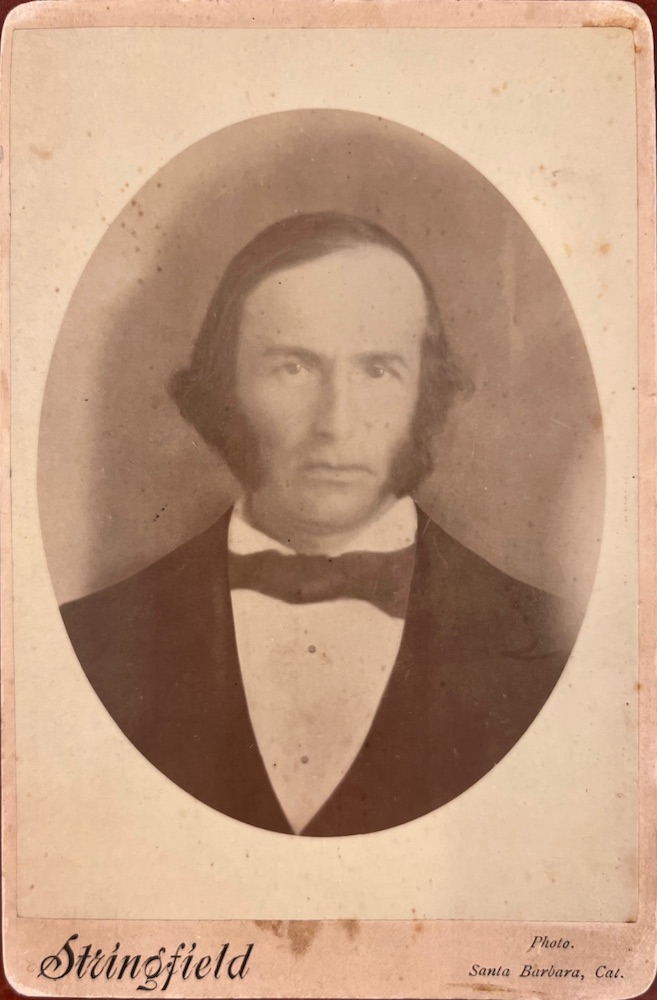

The adobe had been built in 1817 by their grandfather, Domingo Antonio Carrillo, for his wife, María Concepción Pico, whose brother Pío would become the last Mexican governor of California from 1845-46. In 1838, their daughter married José María Covarrubias, a Spanish native of France who became private secretary to Pío Pico, and also served as alcade (mayor) of Santa Barbara, as well as county judge, delegate to the State Constitutional Convention, and State Assemblyman. Nick himself served as County Supervisor, County Sheriff, and U.S. Marshall. The adobe was rife with history that stood poised to be demolished.

Saving the Adobes

By some miracle, ten years later the adobe still stood. After a succession of residential lessees and periods of vacancy, in June 1919, the newspaper reported, “Another of Santa Barbara’s old historic adobes has been reclaimed to lend itself to the artistic needs of the present day.”

J. H. McDonald, who was associated with Flying A Studios and the Portola Theater, saw possibilities in the romantic old adobe and adapted it as studios. “In ‘The Covarrubias,’ he said, “artists and their kin may gather in a congenial atmosphere of informality to sketch from life and to exchange views and exhibit their art.”

In August, he branched out to include the dramatic arts by presenting local author H. Fenner’s one-act tragedy, “The Death Penalty,” with a cast of amateur thespians. The review said, “The old house with its ancient, blackened timbers made a wonderful setting.” Artist and antique dealer Robert Wilson Hyde had lent items for the set, just as he would for the Community Arts Players who formed the following year.

In December 1919, Cadillac tycoon and local arts supporter Clarence A. Black purchased the adobe for $5,000 with the intention of using it as artists’ studios and an art school, which was being promoted by several noted community patrons. When Berkeley theater director Samuel Hume and actor Irving Pichel were hired by the Community Arts Association to produce an extravaganza-style version of The Quest, many of the costumes were made at the Covarrubias Art School. Soon, however, the name and venue for the school changed to the Santa Barbara School of the Arts, which was located in the Dominguez Adobe on the corner of Carrillo and Santa Barbara streets.

The Southworth Era

With the art school established elsewhere, Black sold the Covarrubias Adobe to John R. Southworth, a writer and historian who had lived in Mexico for 34 years before moving to Santa Barbara where he opened an antique and curio store in the Oreña Studios. Southworth remodeled the Covarrubias by cladding the interior with asbestos wallboard and redwood in a Gothic style. Outside, he constructed a wall of cement around and underneath the old walls, making a cradle to insure its survival for another hundred years. The roof of the adobe had lost its original Mission tiles back in 1886 when they were sold to a Montecito resident. Wood panels now covered the willow canes limed with a heavy plaster of mud in which the original tiles had been set.

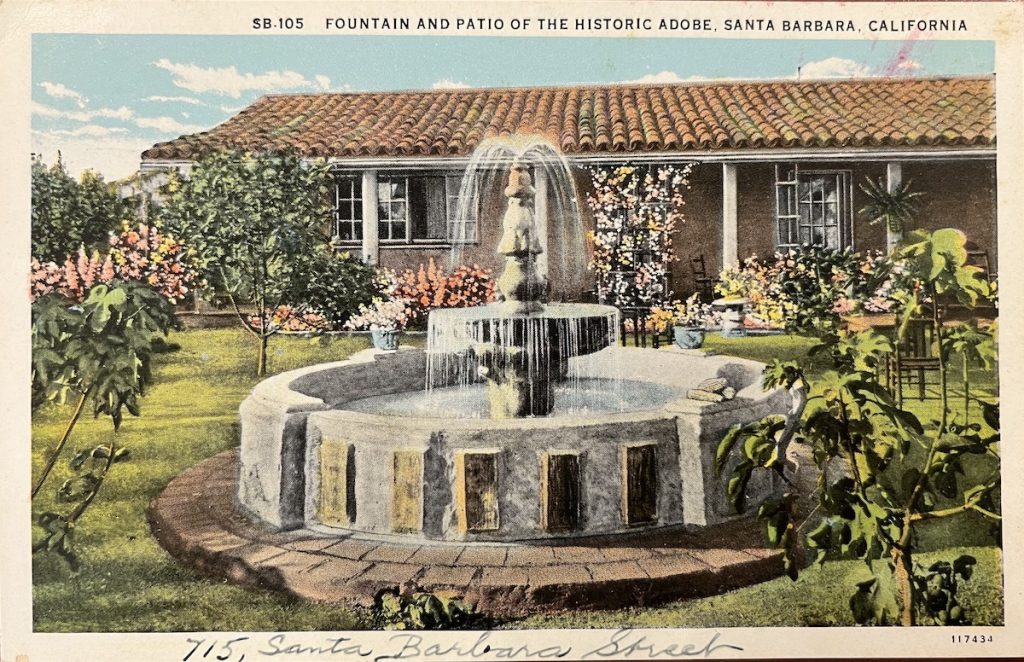

Also in 1920, the Natural History Museum was under pressure to vacate its premises at 930 Anacapa Street so a women’s hotel, the Margaret Baylor Inn, could be built. They announced the sale of their adobe building and hundreds of old “Indian-made” roof tiles. No buyer stepped forward, and the Native Daughters and the Native Sons of the Golden West advocated demolishing the old adobe, which they felt had no historic significance. John Southworth came to the rescue, purchased the 1836 Malo Adobe, and laid plans to move it next to the Covarrubias. “It will be the first adobe in California to be moved without melting away,” he said. By 1924, its resurrection was complete, and it rested across from the Covarrubias, leaving a charming patio between.

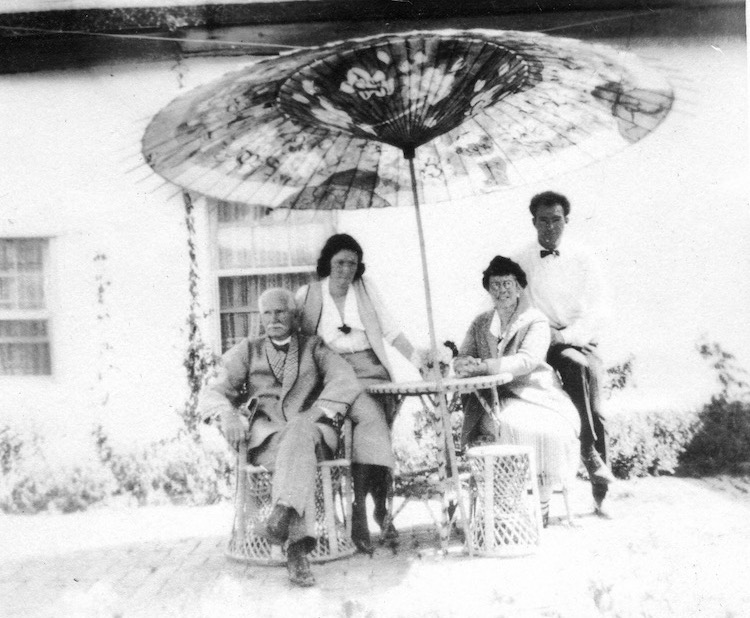

For the next 18 years, the Covarrubias and the Historic Adobe were alternately leased in whole or part by Southworth who periodically lived there and ran his antique business. Lessees included residents who ran a tearoom, antique dealers, a photographic studio, an interior decorating business, shops, and art gallery. In 1932, Mebane Beasley opened a vocal studio at the Covarrubias. After a recital, the reviewer remarked, “The charm of the large room where the recital was held is felt in its lighting of candles and everywhere are to be seen delightful old paintings and furniture while the Steinway piano, in its most original casing, is a work of art.” In keeping with the music theme, in 1935, Roger Clerbois, a founder of the Community Arts Association Orchestra, leased the Covarrubias for his Mozart Society.

Covarrubias Ghost Plagued Businesses

There seemed to be a dizzying turnover rate for businesses at the two ancient adobes, perhaps because of the strange and uncanny noises attributed to the Covarrubias ghost; “The White Lady,” whose baby had died in infancy in 1819. A sister of Nick Covarrubias related that at the midnight hour, the bereaved ghostly mother of the deceased child would move silently through the salon, pulling away the blankets of her spectral bed as she vainly sought her lost child. A chilling sight, indeed!

Stories of ghosts, however, didn’t prevent various groups in town from using the historic setting of the adobes for their events. In 1927, the Strollers, an amateur drama and music group, held its annual Fiesta dinner in the garden of the Covarrubias. Comprised of charming patios with fruit trees growing against the old adobe walls, the garden also had a grapevine which draped itself on a low ramada and festooned across doorways and deep-set windows.

In 1936, Southworth tried to rid himself of both adobes and put them up for auction. The Morning Press report was a bit wistful as it stated, “The buildings, though privately owned, have been among the principal show places of Santa Barbara for years and have been regarded almost in the light of community possessions.” Back in 1931, the California State Chamber of Commerce had marked them as one of 18 points of historic interest in Santa Barbara County.

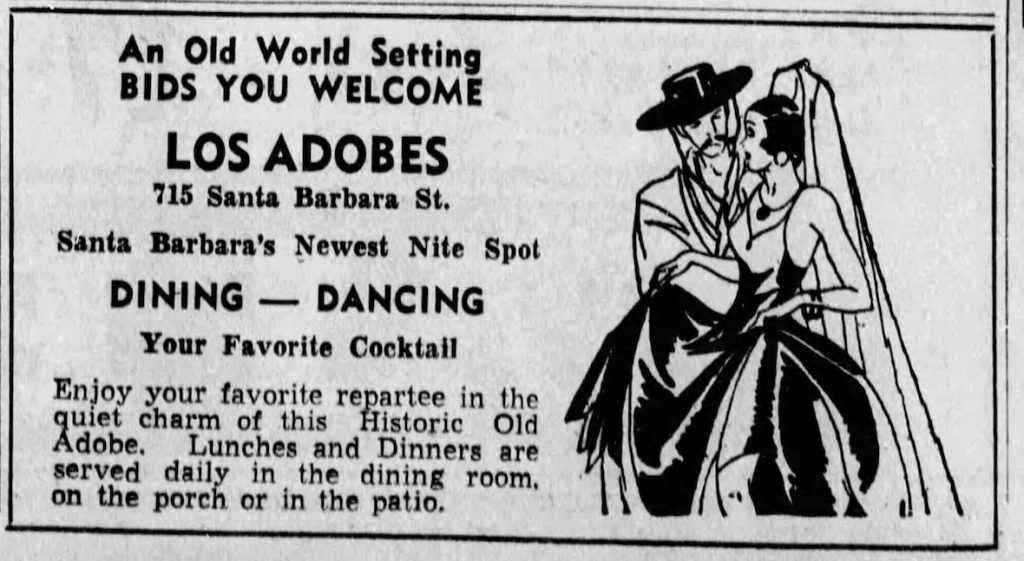

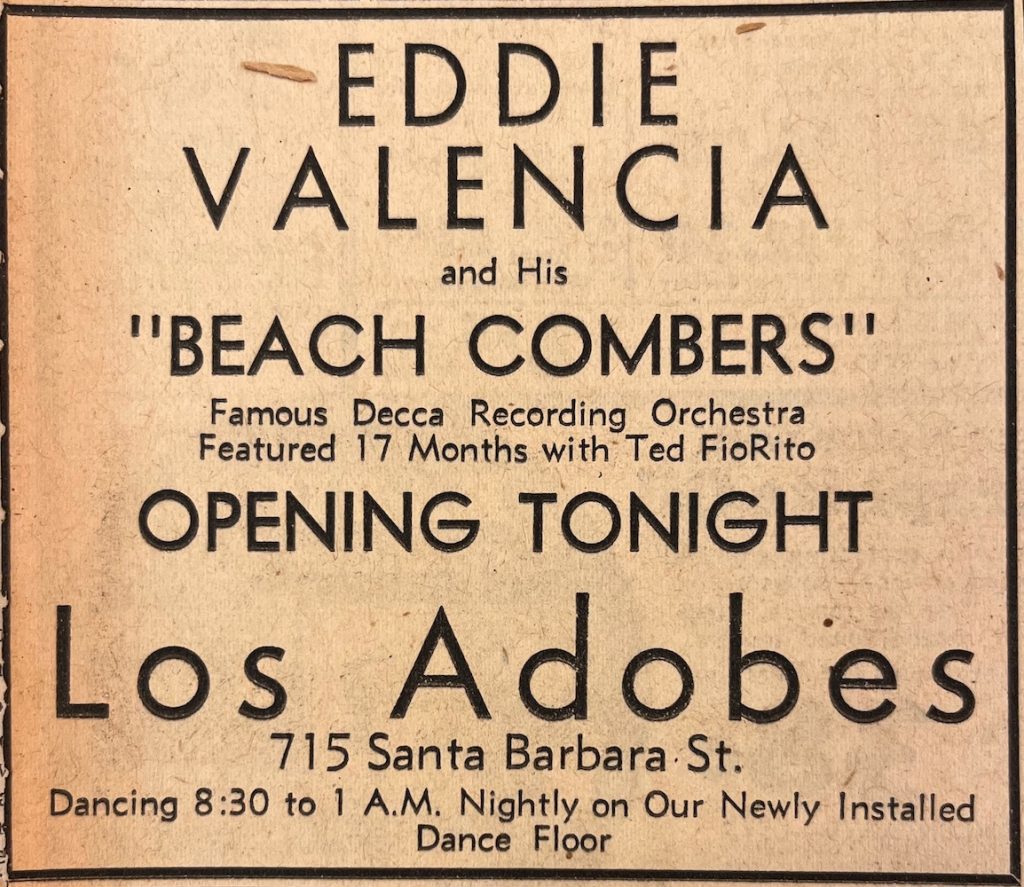

There were no takers at the auction, however, and they were leased out again. Santa Barbarans must have been pleased when the new business, “Los Adobes,” advertised they had opened a night club with dining, dancing, and cocktails. That August, Eddie Valencia and his Beach Combers entertained with their signature Big Band sound tinged with a Hawaiian twang. Dancing began at 8:30 pm on a newly installed dance floor.

Beyond Southworth

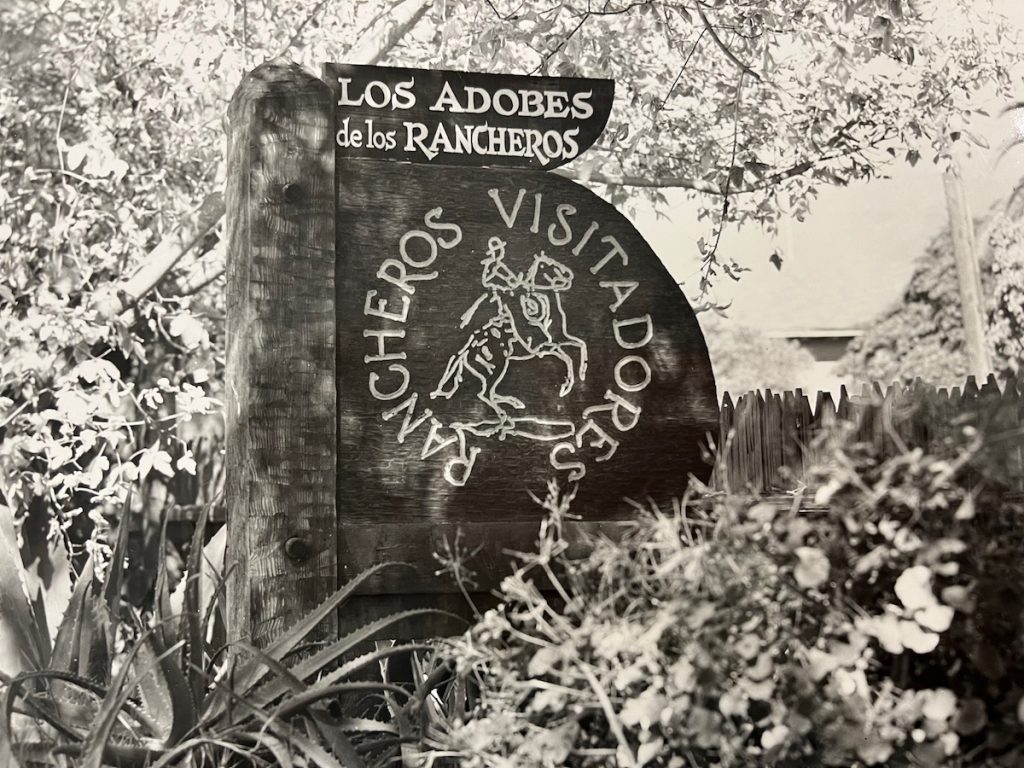

In 1938, Southworth was finally able to sell the adobes. Los Rancheros Visitadores planned to restore and preserve them as a club center, complete with museum and art gallery. Leo Carrillo, direct descendent of the pioneer Carrillo family, became head of the building committee and was assisted by architect Joseph Plunkett. They replaced the shingle roof with tile, restored the adobe walls while adding buttressing, and restored the fountain in the courtyard.

They named the complex “Los Adobes de Rancheros” and invited the public to visit. Donations of art and other California relics provided décor, as did a unique set of paintings of the California Missions by California artist Will Sparks. Fiestas at Los Adobes saw dozens of temporary stalls for horses, collections of stagecoaches, carriages and silver mounted saddles, and lots of festive parties.

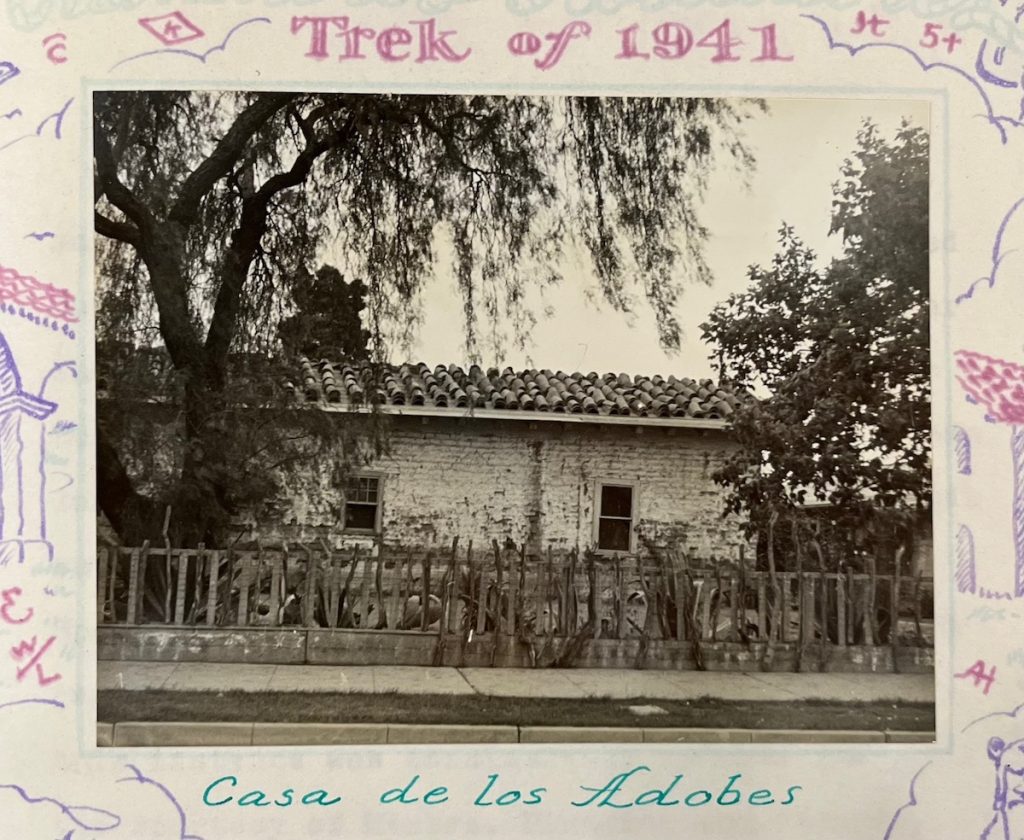

In 1941, the Santa Barbara Chamber of Commerce moved into the adobes. They wanted to have quarters that were more in keeping with the spirit of Santa Barbara, and to move another step forward in preserving its precious landmarks.

During WWII, the Covarrubias was used by various groups working on relief efforts. Afterwards it became the United Nations House which promoted international relief and understanding. There were many affiliates such as Russian Relief, the English-Speaking Union, and the Holland and Scandinavian groups.

In 1947, the County was told they could buy the Covarrubias. They declined.

In 1959, Leo Carrillo unveiled a plaque marking the Covarrubias as a State Historic Landmark. (It is also a Santa Barbara Landmark and on the National Register of Historic Places.) Then, in 1963, the Santa Barbara Historical Society broke ground on the site of the former gas plant on the corner of De la Guerra and Santa Barbara streets for their new adobe brick museum. The following year they purchased the adjoining property with the Covarrubias and historic adobes.

Now over 200 years old, the adobe walls of the Los Adobes have seen and hosted two centuries of Santa Barbara’s history. Besides being a popular place for weddings and community and private events, it has kept Santa Barbara’s history alive by providing a venue for lectures, talks, films, and demonstrations.

Maintenance on Los Adobes has been continuous ever since the Santa Barbara Historical Museum took over stewardship of the adobe relics. The latest costly restoration and preservation effort was made after the heavy rains of 2022-23 caused significant damage.

Sources: Stamps.org. “The Portola Festival” by Harry K. Charles, Jr. at https://stamps.org/Portals/0/ArticlesDistinction/Portola-Festival.pdf, accessed 26 December 2024; contemporary newspaper articles; Trek Book 1941 of the Rancheros Visitadores, City Directories, U.S. Censuses, Obits.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.