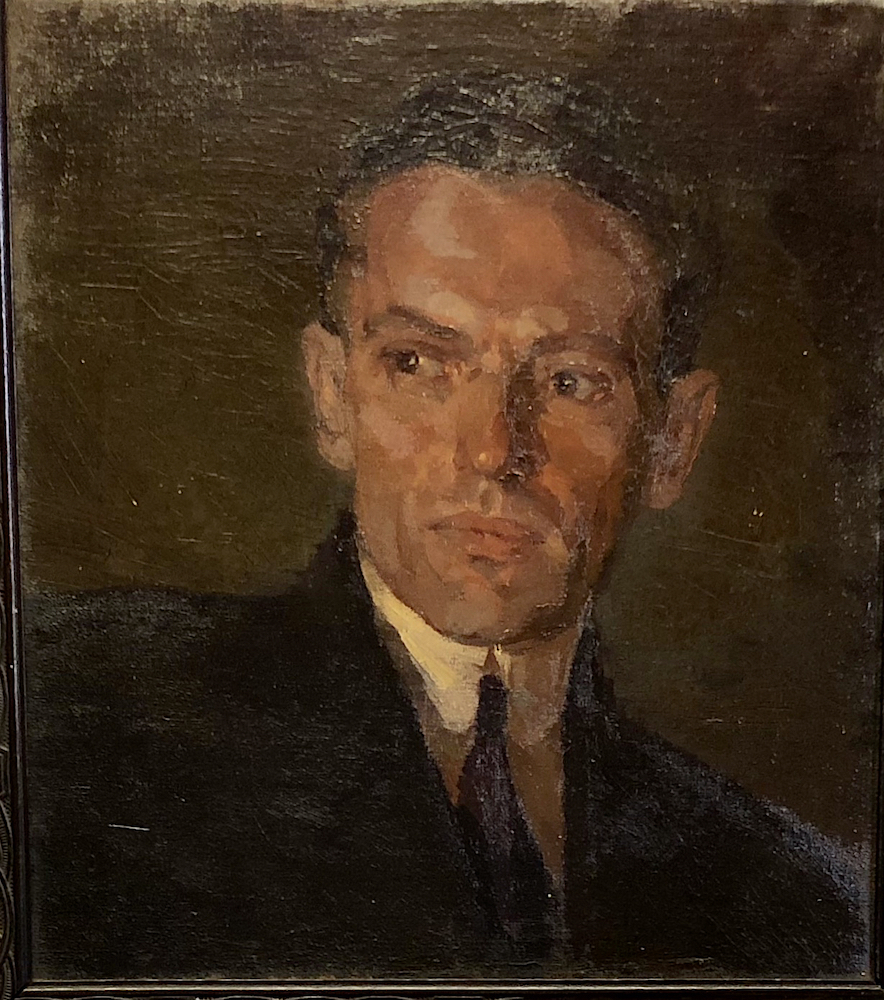

Dudley Saltonstall Carpenter: A Life in Art

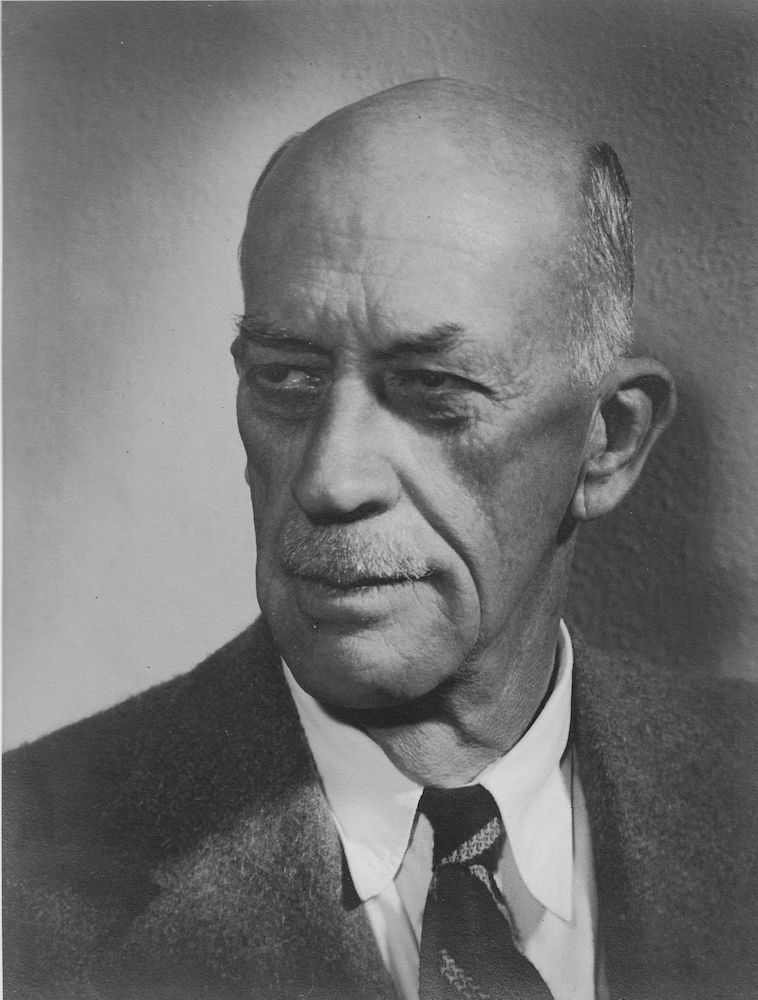

Upon the death of beloved local artist Dudley Saltonstall Carpenter in 1955, the newspaper expressed the esteem in which he was held and commented that he had continued to paint to the end of his full and creative life. And what a life that was. Born into a military family in 1870 in Nashville, Tennessee, he and his siblings were shifted from post to post during the final settlement of the West. Those posts included Fort Laramie, Wyoming; Fort Hartsuff, Nebraska; Fort Douglas, Utah; and Fort Vancouver, Washington.

Eschewing the stars and stripes of a military career and the stethoscope of a doctor, Dudley professed an inclination toward art and enrolled in the Art Students League in New York. In 1892, his parents sent him to Paris to continue his studies at the Académie Julian. Touched by his parents’ largesse, he wrote his mother saying, “It is hard to write what I wish to say. That I always thank God for such a good mother and father. And I Pray I may be a good son to them.”

Despite his enthusiasm for art, Dudley’s letters home reveal he did not find instant success in Paris. When his drawings were reviewed and no notice was taken except to say they were ridiculous, he wrote home saying, “It is rather discouraging but I shall keep on with art a little longer.”

Truly an innocent abroad, Dudley related an incident that left him bemused. One afternoon a woman had knocked on the door of his Paris flat to beg for money, and when he finally understood what she wanted, he offered her two sous just to be rid of her. “She was insulted,” he wrote to his sister, “and immediately said she couldn’t accept so insignificant a sum. As she had just told me she had been sick and had nothing to eat, I didn’t expect her to refuse anything. She handed me back the copper and walked out with her head held very high.”

Subsequent letters home show increasing approval of his work. In April 1895 the Brooklyn Daily Citizen was able to announce that Carpenter had a painting hanging in the Champs de Mars Salon in Paris along with those of Albert and Adele Herter, who were already quite famous. He had “arrived,” so to speak, and spent the next 16 years painting, exhibiting, and teaching in New York and the states of the Eastern Seaboard.

Margaret Van Wagenen Carpenter

While studying in Paris circa 1909, Dudley met Margaret Van Wagenen. Margaret was a protégée of Anne Evans, who was a noted art patron in Denver. Evans had made it possible for Margaret to attend the Chicago Art Institute and the Art Students League in New York.

In 1906, Margaret had returned to Denver and rented #24 Brinton Terrace, a once elegant, upscale row house constructed in 1882. Van Wagenen’s vision was to assemble local artists under one roof where they could unite in a common cause and inspire one another. Writing in 1947, Edgar C. McMechen said of Margaret, “The blithe and shining spirit of this Denver girl has kept her memory verdant among Denver artists to this date.”

In 1909, Margaret returned from New York with a beau in tow, Dudley Carpenter. The two married in January 1910, and he joined her in her stained-glass work and taught art and painted landscapes, portraits, and public murals. To this day, his Pied Piper of Hamelin and King Arthur Recovering the Magic Sword Excalibur grace the walls of the Decker Branch of the Denver Library.

Recalling his time in Denver in 1951, Carpenter still chuckled at the time passersby noticed him sketching en plein air on a road near town. “There’s an artist,” said one, “I’ve seen them in the movies. They are very immoral.”

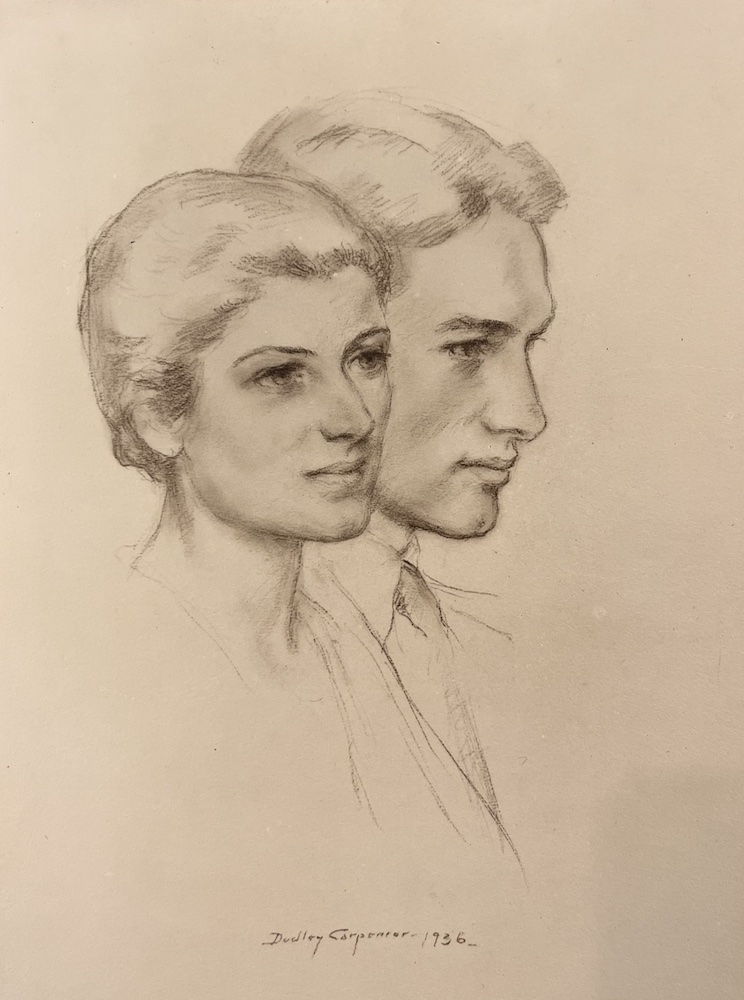

The Carpenters’ sons, Gilbert and Theodore, were born in 1912 and 1914 respectively. In 1917, Dudley exhibited a drawing at the Montclair Museum in New Jersey. The reviewer wrote, “Perhaps none has attracted more attention than Dudley S. Carpenter’s An Afternoon Stroll. It is a portrait of a mother and her two sons. Admirably drawn and beautiful in composition and color, the handling of the figures becomes of interest with the subject. And the Subject is fascinating. One cannot help wondering what life has in store for two such beautiful boys.”

The drawing, of course, was of Margaret and her sons, and life had plenty in store for the young family, not all of it good.

Santa Barbara

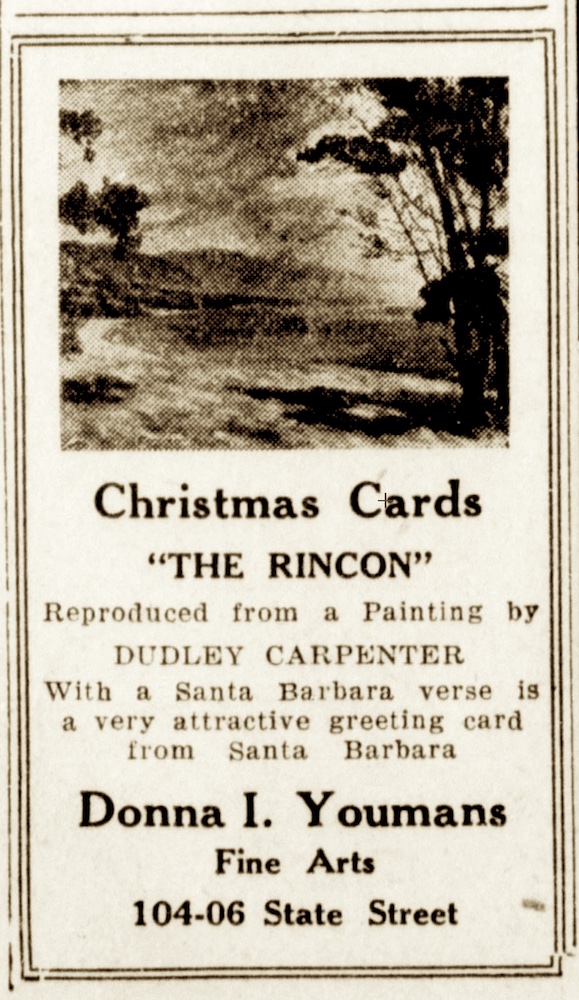

In 1920, the family moved to Santa Barbara where they leased a house in Mission Canyon. Dudley planned to work as a decorator and was willing to take on any sort of “bread and butter” work, like selling an image of his landscape The Rincon for Christmas cards. He found that portraiture, however, was more lucrative. He also joined Fernand Lungren, Albert Herter, and DeWitt Parshall at the newly opened Santa Barbara School of the Arts where he and Oscar Borg taught outdoor sketching classes.

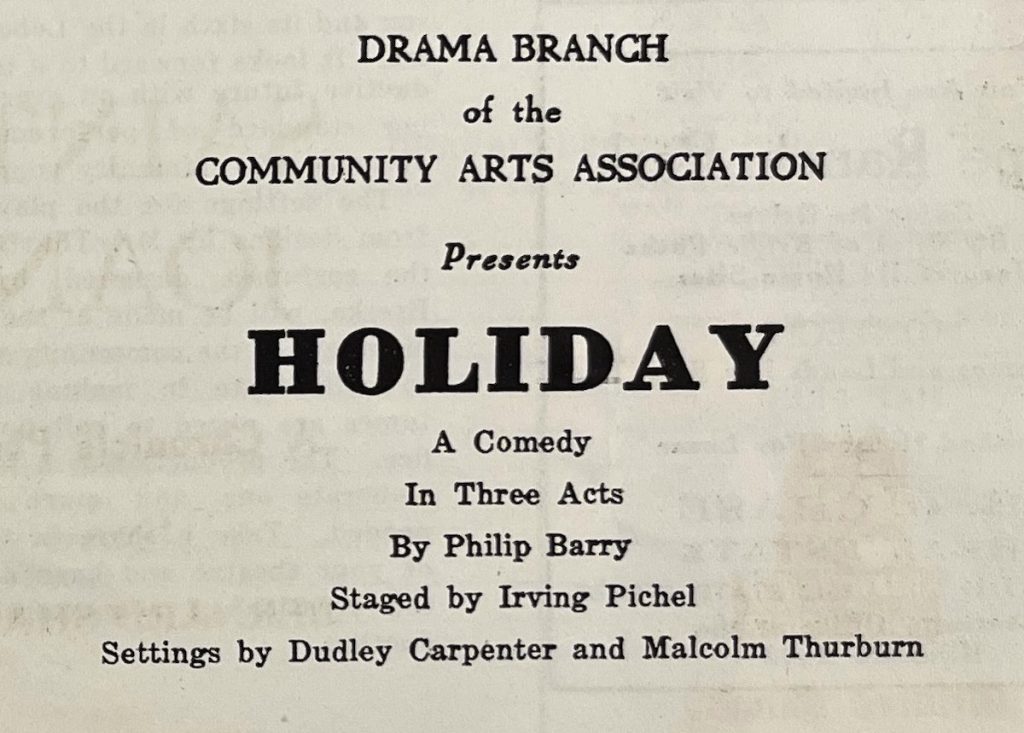

Dudley had arrived in Santa Barbara at the naissance of a cultural renaissance which began with a Community Chorus and Community pageant before organizing very quickly into the Community Arts Association with a theater and a school for the arts. Dudley involved himself in all of it and occasionally acted in the Community Arts plays and constructed and painted sets for several productions.

At the end of December, Margaret, who had developed cancer, died at their home in Mission Canyon. The boys, aged 8 and 6, were eventually sent to Montclair, New Jersey, to be raised by Dudley’s sisters. He stayed behind and endeavored to find his way and make a living through art in Santa Barbara.

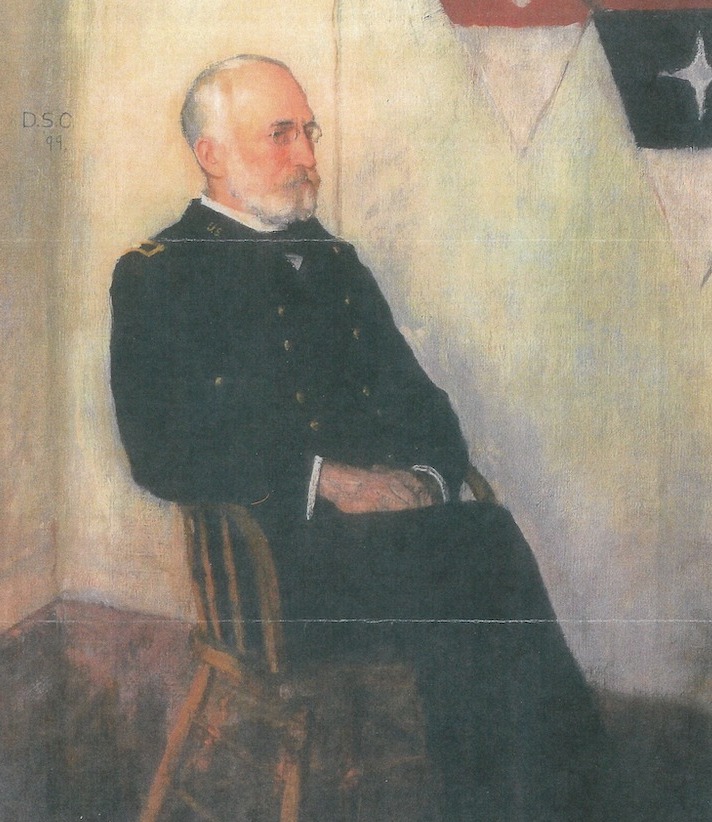

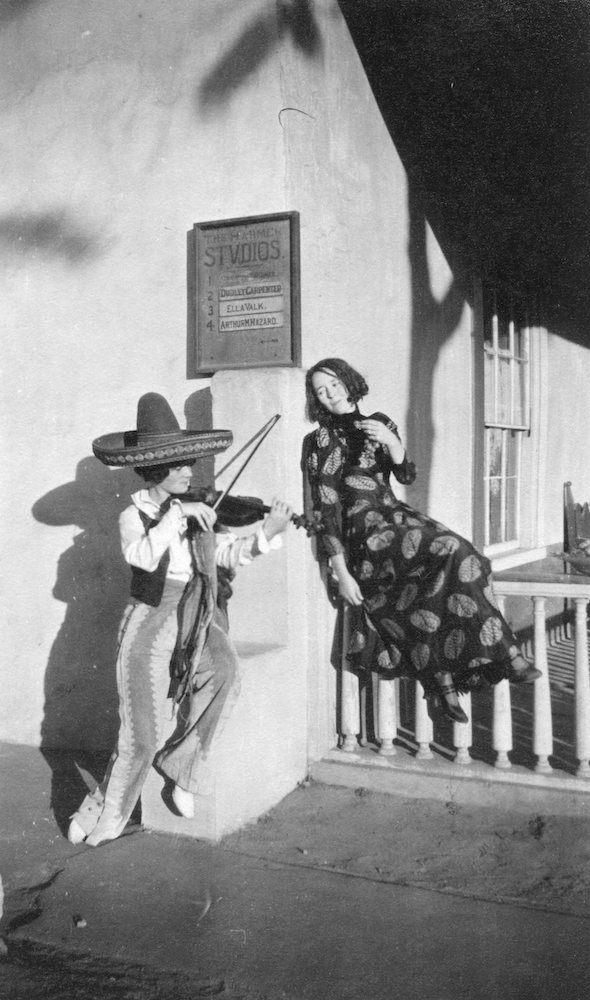

In February 1921, Dudley opened a studio in The Patio, a lunch and tearoom that had recently opened in the old Oreña adobe on East De la Guerra Street. In September he moved to a studio at the Harmer Studios, which were attached to the old Yorba/Abadie Adobe. Alexander Harmer, an artist himself, had become famous for memorializing the old Spanish lifestyle through his colorful and evocative brush.

The Morning Press announced Carpenter’s studio opening. “Locally he has painted many portraits of Santa Barbarans,” wrote the reporter, “but he also has virile powers in the treatment of landscape and his studio shows a number of these. A handsome little canvas portrays the grand live oaks of El Arbolado on the Riviera and a fine marine has for its subject the cliffs of La Jolla, rising out of the blue Pacific.”

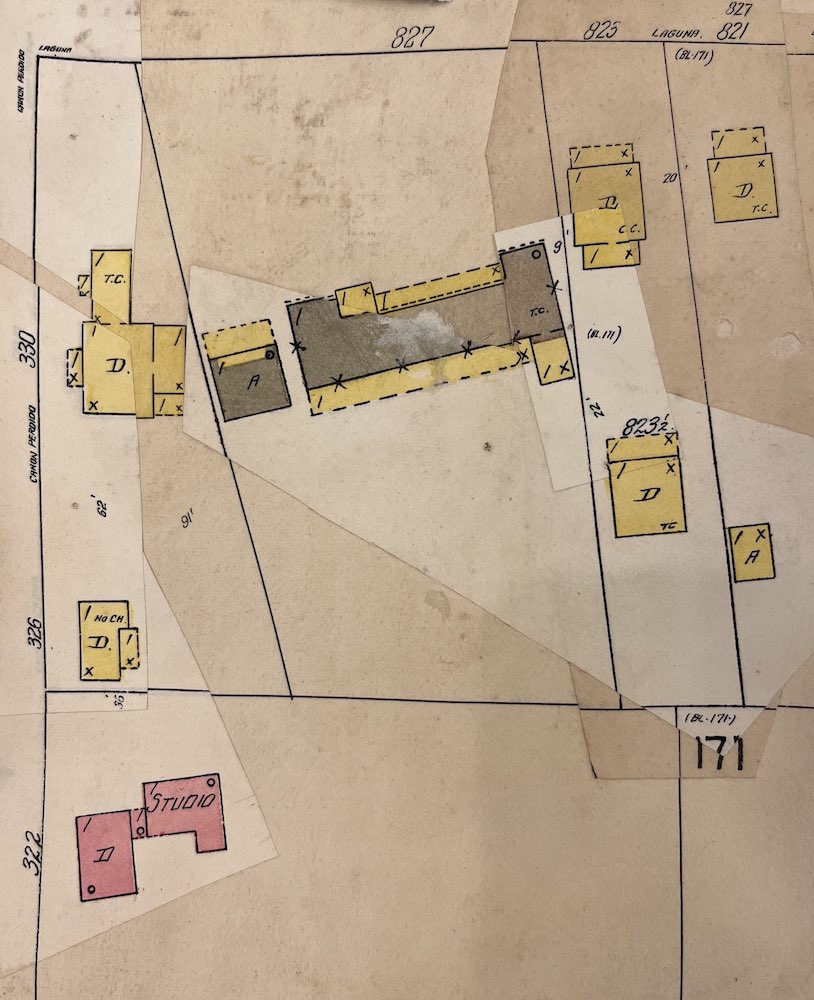

Dudley had found a home among the artists of the Santa Barbara Art Colony. He painted portraits of the Carringtons, influential cultural advocates, and Louise Vhay, who had designed and owned El Arbolado. He threw himself into the exciting and optimistic time of Santa Barbara’s artistic explosion and involved himself in all aspects of it. After the 1925 earthquake, he established a studio and home at 322 East De la Guerra Street.

Supporting the Arts

In June 1924, Dudley was one of 16 artists who met at the new El Paseo de la Guerra, the complex built by Bernhard and Irene Hoffmann, who were great supporters of renovating Santa Barbara’s architecture into a Spanish style. That evening, the artists formed the Santa Barbara Art Club. Dudley served on the house committee of the club, which was later called the Santa Barbara Art League.

In 1926, Dudley created ceiling murals depicting stories of St. Francis for the anteroom of the El Paseo Restaurant. The Daily News declared them genius and called for more public art to enrich the appearance of the town. In 1939, a new entrance to El Paseo from Anacapa Street brought Dudley back to mural work, this time using the prehistoric pictographs of the bulls of the Altamira Caves in the Pyrenees for inspiration. Portraits were still his main genre, however, and Santa Barbara notables such as Community Arts Orchestra founder Mrs. Frederic Saltonstall Gould; eminent music scholar, pianist, and composer Sir Donald Francis Tovey; and Community Arts Players director Nina Moise were immortalized in red chalk portraits.

Dudley was teaching at the School of the Arts in 1929/30 when Channing Peake and Campbell Grant enrolled. He soon became a mentor to them and to an increasing number of young art students hampered by the Depression. His own son, Ted, returned to Santa Barbara in 1937 and joined the group of younger artist friends that also included Bobby Hyde, Jack Hamilton, Gordon Grant, Polly Forsyth, and Katie Schott. His studio at 322 East Canon Perdido Street became a gathering place for “the gang.”

Dudley’s yard abutted that of artist and architect Louise Vhay, who had renovated the Gonzalez-Ramirez Adobe and later created the art colony of El Caserio Lane. Every year Vhay and Carpenter hosted an annual Fiesta party in their adjoining gardens in August. Like all artistic things in Santa Barbara, Dudley had taken to Fiesta from its inception in 1924. Back then, he had taken a dress suit he’d purchased in New York in 1895 and had it “Hispanicized” with a stripe running down the trousers. He also had the tails cut off and the reverse of the coat faced with color. Instant caballero!

For the Vhay/Carpenter party in 1939, Katie (Schott) Peake updated Dudley’s outfit with a new sash. The party spilled over into Dudley’s studio where an unfinished chessboard, a present for Jack Hamilton, hung on the wall. The dark squares were ornamented by Ted and Dudley and their artist friends, including Louise Vhay, Channing Peake, Campbell Grant, and Rico Lebrun.

As the Depression deepened, Dudley found that commissions for his portraits had dwindled, so he took up sculpture. He sculpted Hollister and Peake family members, staying at their ranches for weeks at a time. A reviewer in 1938 said, “Mr. Carpenter has been known for years as a painter, and it may surprise many to see him now as a sculptor. The remarkable thing is he seems to be more at home in this medium than in paint.”

The Depression rang the death knell for the School of the Arts in 1938, but Dudley was determined to form a new school. In November 1939, thanks to the patronage of Mrs. Max Schott, a new art center was opened on the renovated and remodeled site of the old School of the Arts. It was dubbed the Alhecama Art Center, but it didn’t survive WWII.

Throughout the 1940s Dudley continued mentoring new artists in town and employing his various mediums of expression. In 1948, he had a one-man show at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. The exhibit consisted of a variety of still-life arrangements, landscapes, and figure compositions. The reviewer said, “Whether Carpenter is painting shells, flowers, or ceramics, he always places some emphasis upon the poetic values of mood and tonal charm.”

In 1955, when he fell ill, the many friends he had helped in their youth visited with him in his home. Though his name today has faded from note, the impact of this gracious and imaginative man on the artists he mentored and the institutions he fostered lives on.

Sources: ancestry.com resources; Letters 1892-1894, courtesy Dudley Carpenter (grandson); contemporary newspapers; The Colorado Magazine, May 1947, “Brinton Terrace” by Edgar C. McMechen, https://www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2018/ColoradoMagazine_v24n3_May1947.pdf; city directories; Sanborn maps; Facebook Page and communications with grandson Dudley Carpenter; letter from Gilbert Carpenter dated February 1978

You must be logged in to post a comment.