La Madrugada de Fiesta

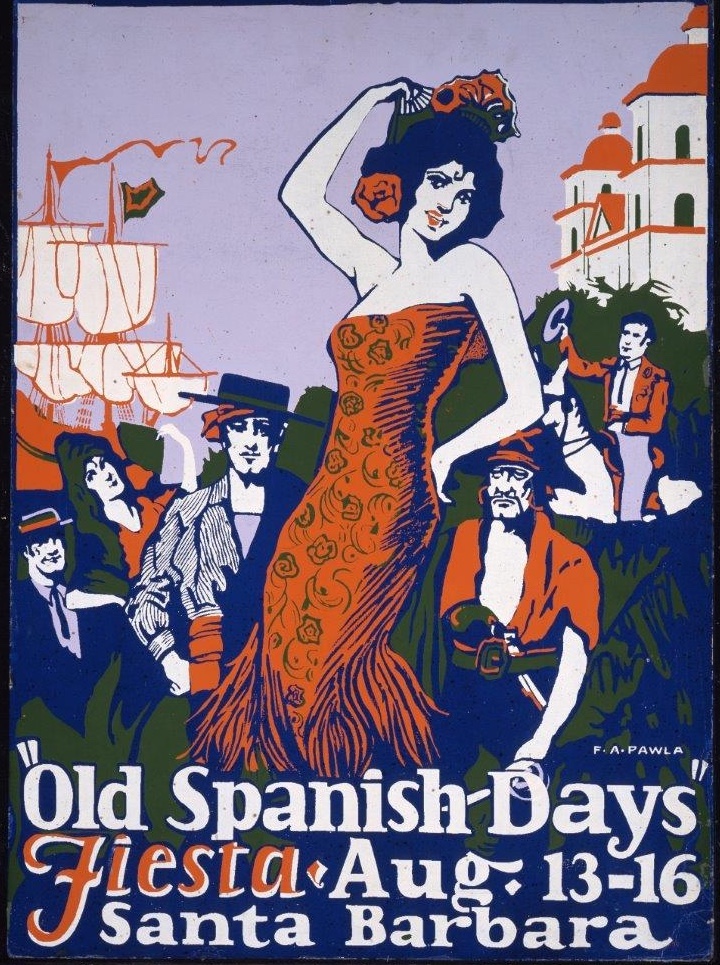

Celebrating the 99th anniversary of its founding this year, Santa Barbara’s Old Spanish Days Fiesta was established in August 1924. Civic celebrations commemorating Santa Barbara’s old Spanish days, however, date back to the December 1886 fiesta celebrating the 100th anniversary of the founding of Mission Santa Barbara. The purpose of that four-day celebration was to raise funds for a new roof for the “Queen of the Missions.”

For the Centennial, State Street merchants and businessmen had put up bunting comingling the American red, white, and blue with the Spanish yellow and red. Residents assumed Spanish costume and a cavalcade of colorfully dressed riders took to the street along with flower bedecked carts and carriages. Brass bands, Chumash Indians, pack trains, and members of the local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) marched along the route. The final vehicle in the parade was a donkey cart driven by Santa Claus, who was accompanied by two little girls on a burro.

After several days of sporting events, horse races, a bazaar, dances, and a rodeo, the festival ended with the Grand Centennial Ball at Lobero’s Theatre. Spanish dancers in full regalia performed historic classics like “La Jota,” and Chumash dancers in costumes of feather and paint danced “El Coyote.” The finale featured both the descendants of the old Spanish families and members of the new Anglo population dancing “La Contradanza.”

The New Lobero Theatre and Fiesta

Ever since the 1886 Centennial celebration, Santa Barbara had been trying to create an annual festival that would bring in visitors and fill the coffers of Santa Barbara’s businesses. Few of those attempts survived more than a few years. In 1924, the latest attempt, La Primavera, was struggling to survive. Its spectacular 1920 inaugural event had proved to be a spectacular financial failure, but the organization continued to operate in a less ambitious form.

By June of 1924, a community theater was approaching completion on the site of José Lobero’s original 1872 theater. Initially slated for renovation, the old theatre was so structurally compromised and outdated that the architect, George Washington Smith, was asked to design a new theater in a stripped-down Spanish style. It would provide a home for the Community Arts Association Players, whose 1920 founding had been inspired by La Primavera Masque.

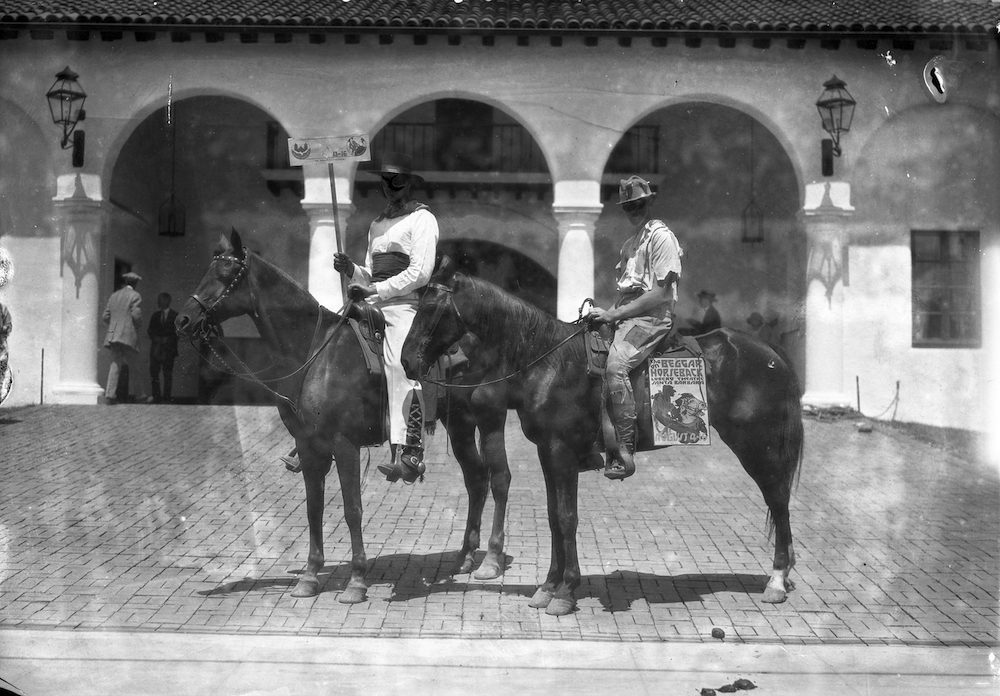

The Broadway hit Beggar on Horseback was chosen as the inaugural play for the new Lobero Theatre. A young actor, who had strut his stuff upon the Potter Theatre’s stage for the Community Arts Players in years past, had a part in Beggar on Horseback in New York. He agreed to abandon the role and come to Santa Barbara to take charge of activities for the opening of the theatre. He became executive director of both the Community Arts Association and the Lobero Theatre. His name was Hamilton MacFadden, and he would go on to become a renowned theater and movie producer and director.

Preparations for Old Spanish Days Fiesta

Planning for a celebration for the opening of the new theater began in earnest in June. MacFadden arranged with the hotels and the Southern Pacific Railroad to give special discounted rates for celebration visitors before inviting the business community to meet at the School of the Arts. Charles Pressley, owner of a women’s clothing store on State Street, became the chairman of the committee to plan a carnival. It would be a life-altering endeavor for Pressley; he became the executive director of Old Spanish Days and served for nearly 25 years.

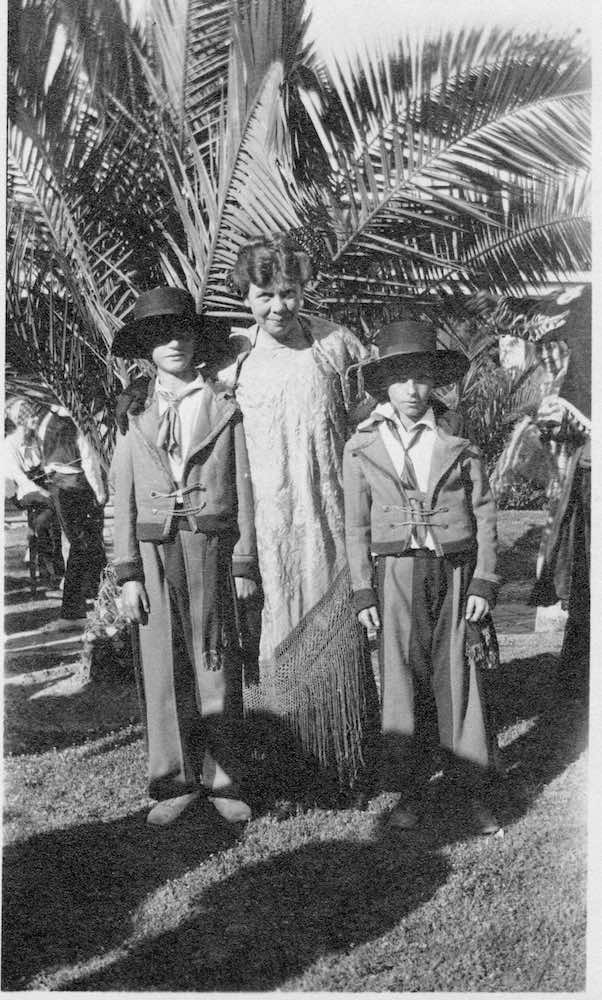

The committee wanted to highlight all aspects of Santa Barbara life including sports, music, and entertainment with a special emphasis on its historic Spanish past. All clubs and organizations from the Aero Club to the Rotary Club were asked to participate with floats for the parade or dances and other entertainments. All citizens were encouraged to start dressing in Spanish garb immediately, and examples of such attire were displayed in store windows.

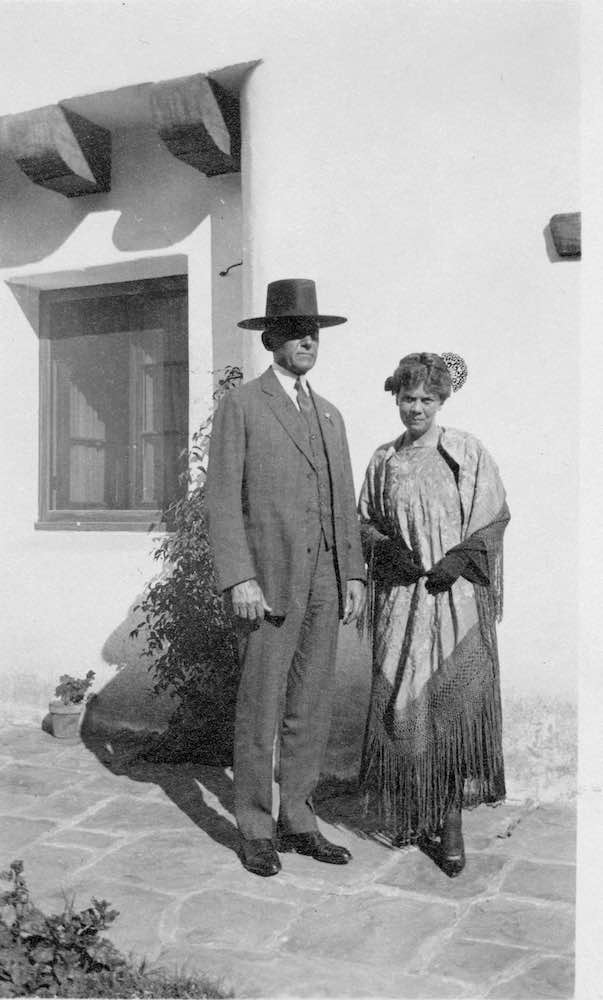

The public responded enthusiastically. Montecitan Frederick Forrest Peabody and wife, Kathleen Burke Peabody, recruited their French bulldog to participate. Christopher Columbus Cabot began appearing in public, reported the press, “all dolled up in a bright burnt orange surcingle and sash. He evidently knows he has a Spanish name because he conducted himself like a little Don.”

The press also reported that the City Attorney might set a risqué new style for the event. When asked what he was going to wear during Fiesta, he responded, “Why, I don’t know that I shall wear anything!”

City Manager Herbert Nunn, however, had always wanted to be a bold, bad pirate and sail the bounding main. “When Don Cabrillo’s caravel comes scudding into Santa Barbara on August 13, look for the toughest, fiercest, longest mustachioed hombre on the afterdeck and you’ll find me.” Clearly Fiesta was going to indulge the fantasies of Anglo Santa Barbarans entranced with the romanticized Spanish past.

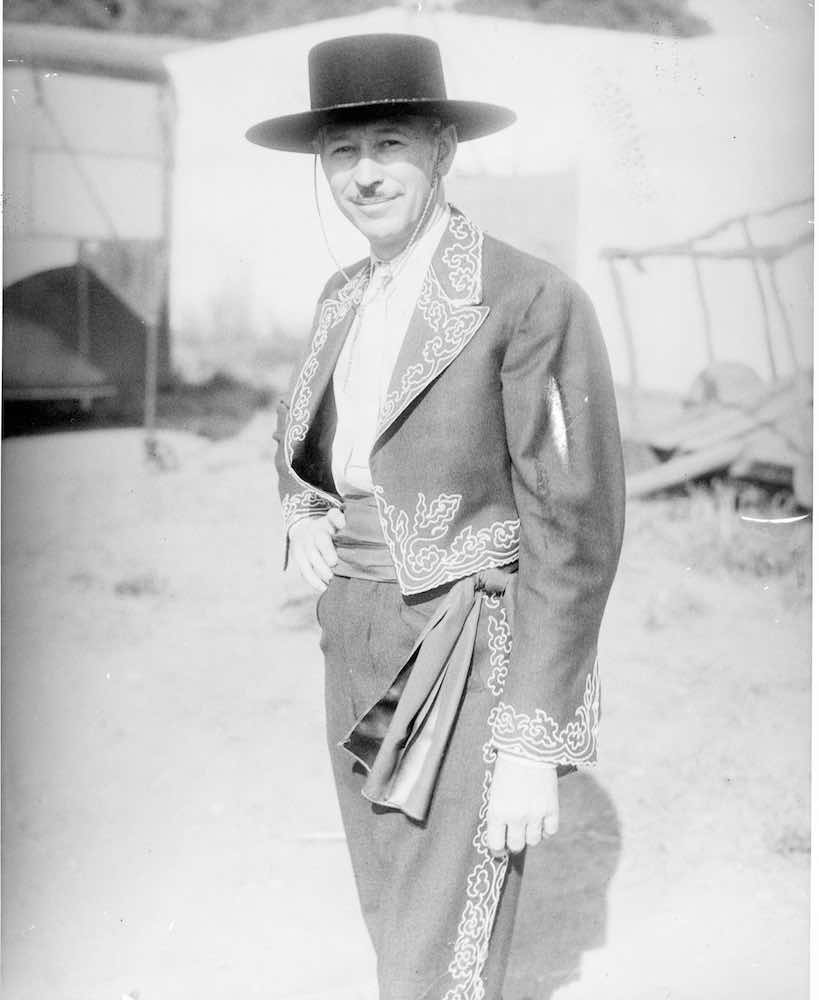

As far as costumes, City Assayer W.W. Smith was not to be outdone by the manager. He was determined to become a toreador. “I’ve grown accustomed to wearing ‘shorts’ as scoutmaster of Santa Barbara’s crack Boy Scout troop,” he said, “hence I feel quite at home in the gold-embroidered ‘shorts’ of a redoubtable toreador. And I like the idea of the little tri-cornered hat, too.”

Others got into the Fiesta spirit in another way. In the “Who’s Who in Police Court” column by “Jove,” the reporter writes, “P. Mario, aged 31 was making ready for ‘Old Spanish Days’ to be celebrated and had 75 gallons of wine all put up in two barrels… The police got smell to the liquor last night, raided Mario’s place, seized the booze, arrested Pietro and spoiled his whole celebration.”

Kangaroo Courts

In the hands of vigilantes, kangaroo courts violate allprinciples of law and justice. In the hands of fundraisers, kangaroocourts are lighthearted, humorous events. The first kangaroo court for Fiesta convened in the exact center of De La Guerra Plaza. The “Honorable” Hamilton MacFadden was the judge. His deputies were ordered to “fare forth” in search of vicious criminals, particularly scofflaws, who were in violation of the ordinances of the day.

These ordinances included a prohibition against gum chewing in public at a gait exceeding 20 chews per minute. Fines were one thin dime for each chew exceeding the limit. If the offense was committed on the sunny side of the street, the fine doubled. Another law stipulated that only Spanish hats could be worn on State Street. Violators were arrested and not freed until a fine of 50 cents was paid. Also, all smoking in Santa Barbara, except by the judge, jury, deputies, and newspapermen, was prohibited.

Ordinance Number 110 said no citizen could comment on the heat, cold, drought, 50-percent window lighting, or the Southern California Edison Company in general. The company had to figure out how to save power and make more money. (A conundrum they still face in 2023!)

Roger Clerbois, a founder and director of the Community Arts Orchestra, was “pinched” for walking the streets in daytime. The court held that he was a night owl and had no business abroad in daytime. Max Fleischmann, famous polo player and wealthy yeast impresario, was taken into custody because he happened to be passing by. The entire Frederick Forrest Peabody family – including doggie Christopher – was brought before the judge because they lived in Montecito. Christopher was also charged for venturing abroad without his toreador costume. Chris tried to avenge himself by amputating the court’s left leg, before paying his 99-cent fine.

And on it went. Best perhaps was that the Chief of Police, Lester Desgrandchamps, was arrested for impersonating an officer. He pled not guilty, which made it worse! The courts were convened several times during the weeks before Fiesta.

Civic Participation

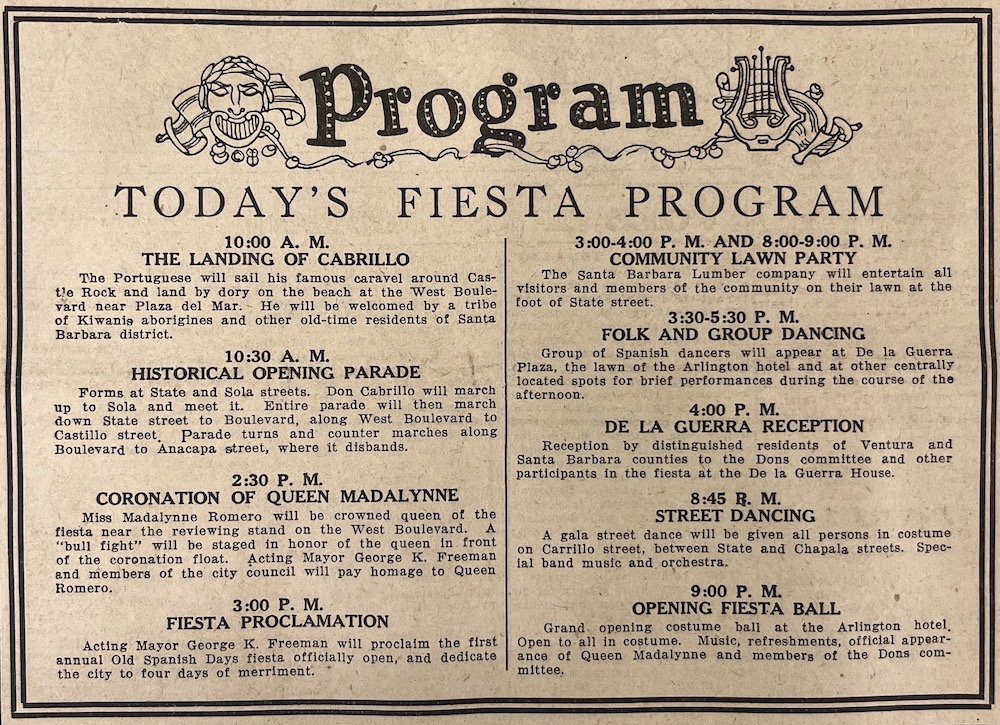

The Executive Committee for Old Spanish Days asked Santa Barbara’s business and civic organizations to participate in the carnival. The Kiwanis agreed to take charge of the landing of Cabrillo after the yacht club defaulted when most of its members said they were going to a regatta in San Diego that week. They arranged for a replica of a Spanish Galleon to carry out the ahistorical landing of Cabrillo. (The explorer never set foot on Santa Barbara soil, though he did die on one of the Channel Islands, several of which seem to vie for the honor.) The Exchange Club was to provide the ‘49ers, the Rotarians represented Fremont’s army, the Elks provided a band, and members dressed in monks’ robes.

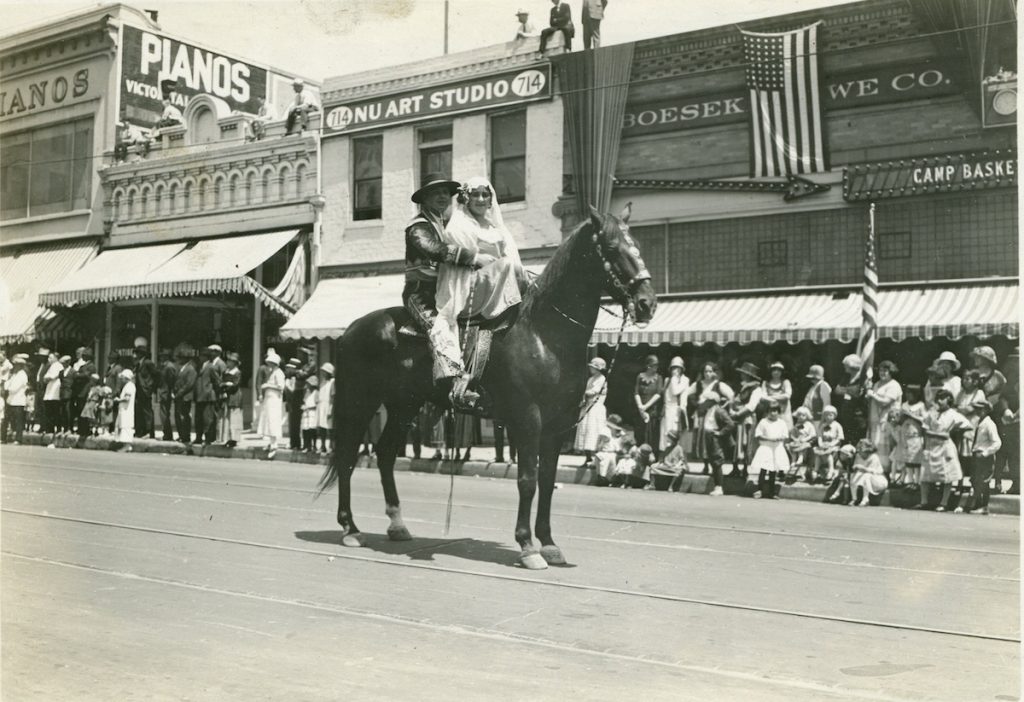

MacFadden called on businesses to provide 200 artistic floats. The sports committee made arrangements for a rodeo, swim races, horseshow throwing, and golf and tennis matches. La Primavera Association donated the Primavera flags to the cause. A very successful fundraising event, the contest for Queen of Fiesta, saw nearly a dozen Santa Barbara belles competing for votes, which cost money. Madalynne Romero beat out all competition on the last day by securing a stupendous lead in votes, all of which translated as funding for Fiesta. Dwight Murphy, Adolfo Camarillo, and Ed Borein arranged for the equestrian portion of the opening parade, which featured descendants of the old Spanish families and the artistry of hidalgo and caballero culture.

On August 13, the festivities began at West Beach when the famous galleon sailed around Castle Rock to land Cabrillo, and the first Old Spanish Days Parade began its march down State Street. Three days later, with all finances in order and running in the black, the city knew it had finally secured its annual festival.

(Sources: Ancestry.com; newspapers.com; Santa Barbara Morning Press and Daily News; Community Arts and theater files at Gledhill Library and UCSB Special Collections)

You must be logged in to post a comment.