Kenneth Rexroth: A Poet of Montecito

If I had to pick a favorite park in the world, it would have to be the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. Not just for its rolling green lawns, ornamental fountains, and sycamore-lined promenades, but for its marvelous statues and busts. Instead of honoring the typical senators and soldiers, the Jardin du Luxembourg also features memorials to French poets – Verlaine, Baudelaire, Murger. If Montecito were to follow the lead of the Parisians and memorialize a poet, it should be Kenneth Rexroth.

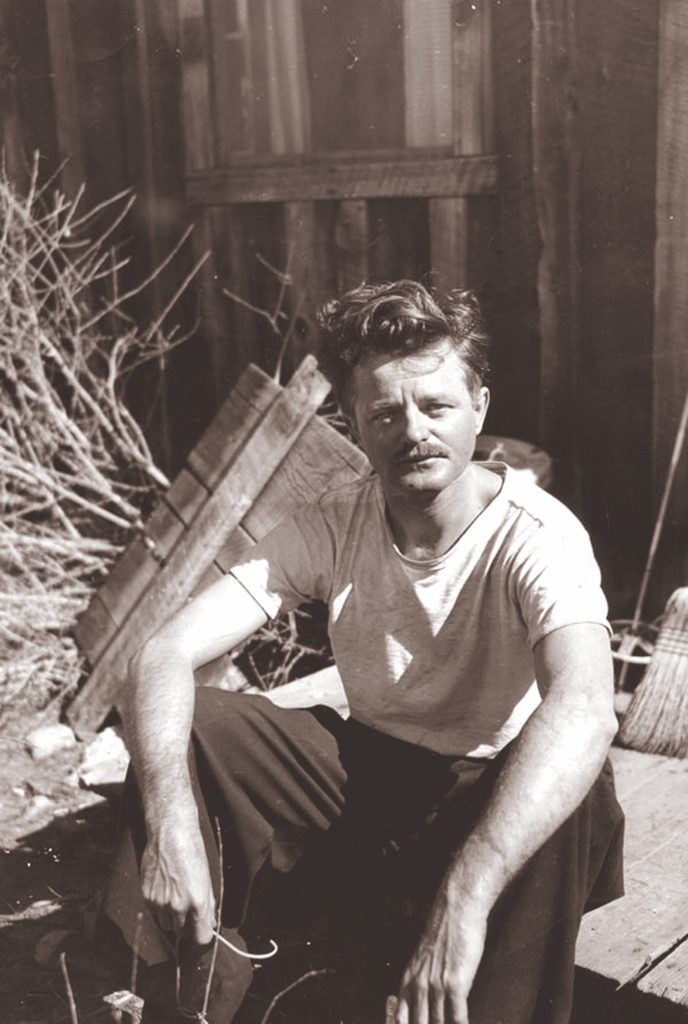

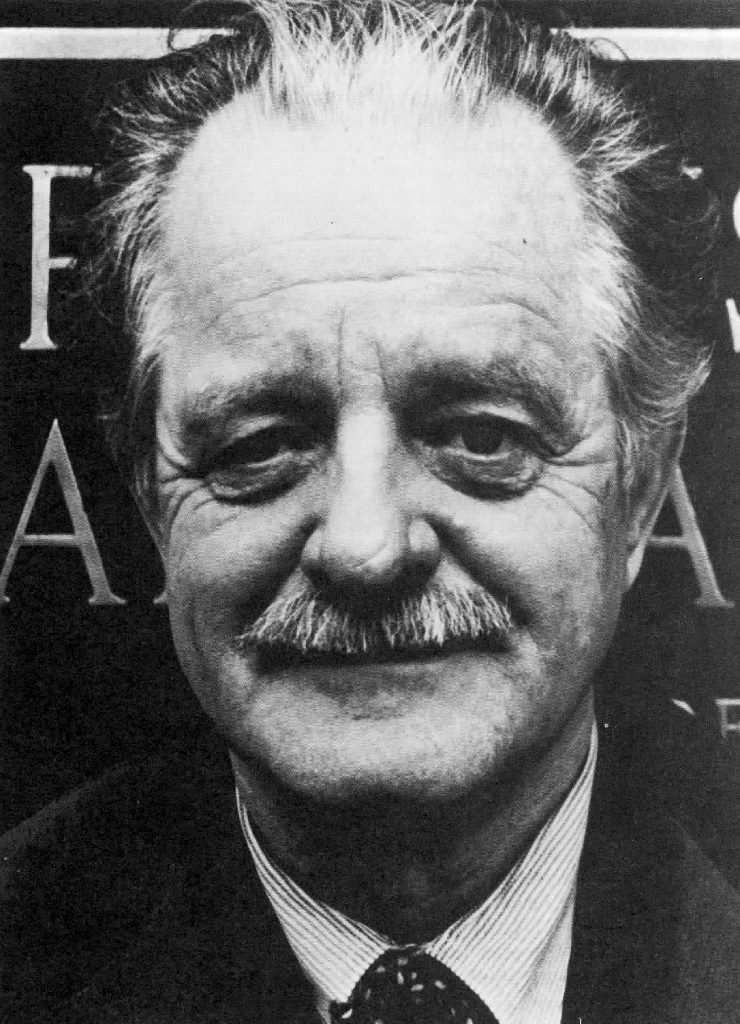

While Rexroth is more generally associated with San Francisco, he lived in Montecito for the last 14 years of his life – more than enough time for Montecito to lay some claim to him. And it would be a claim well worth making, as Rexroth was a seminal figure in 20th-century American arts and letters. A true Renaissance man, Rexroth not only was an innovative and influential poet but a talented painter, editor, translator of Japanese and Chinese poetry, educator, social critic, outdoorsman, and raconteur, as well as a notorious lover of wine and women (he married four times).

Although Rexroth’s body of work stands solidly on its own, he is perhaps best known today as a mentor to several younger writers who would go on to play significant roles in some of the most important West Coast literary and cultural movements of the last century. While living in San Francisco in the 1940s, having already established himself as a highly regarded poet, Rexroth presided over lively bohemian soirées in his Potrero Hill flat. At such events, a swirl of young writers, artists, and intellectuals would hotly debate literature and politics, passionately recite their poetry, drink wine, and dance through the night. Such an important number of poets and intellectuals emerged from this Rexroth-inspired milieu of the late 1940s that this cultural moment is now referred to as the “San Francisco Renaissance.”

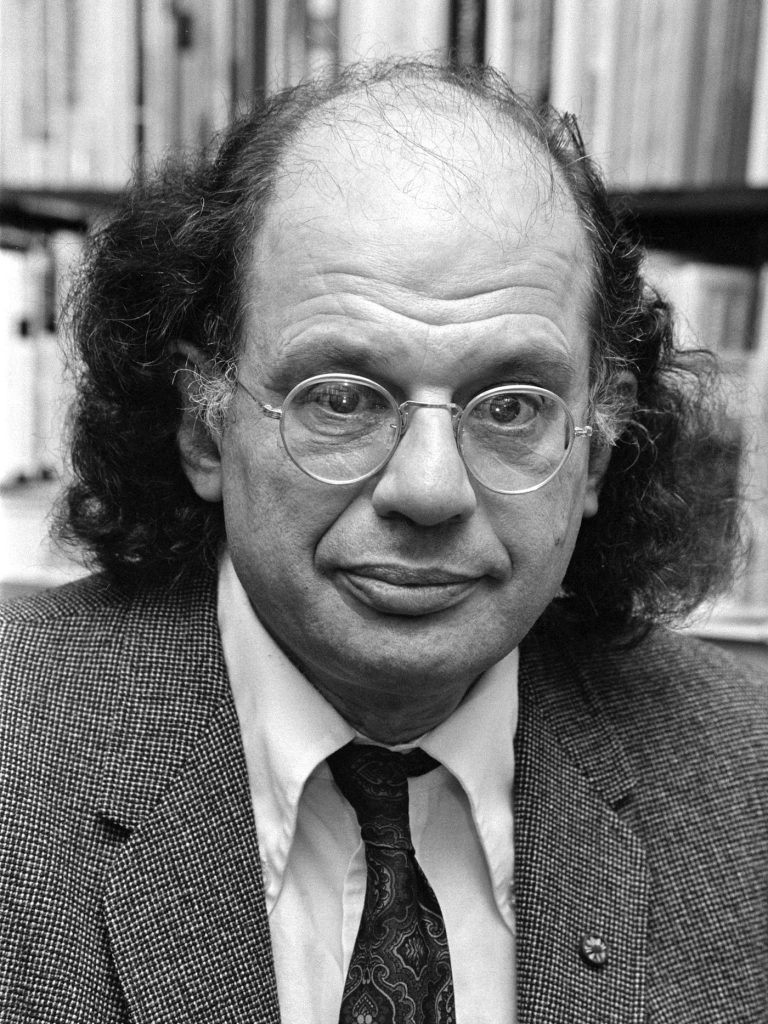

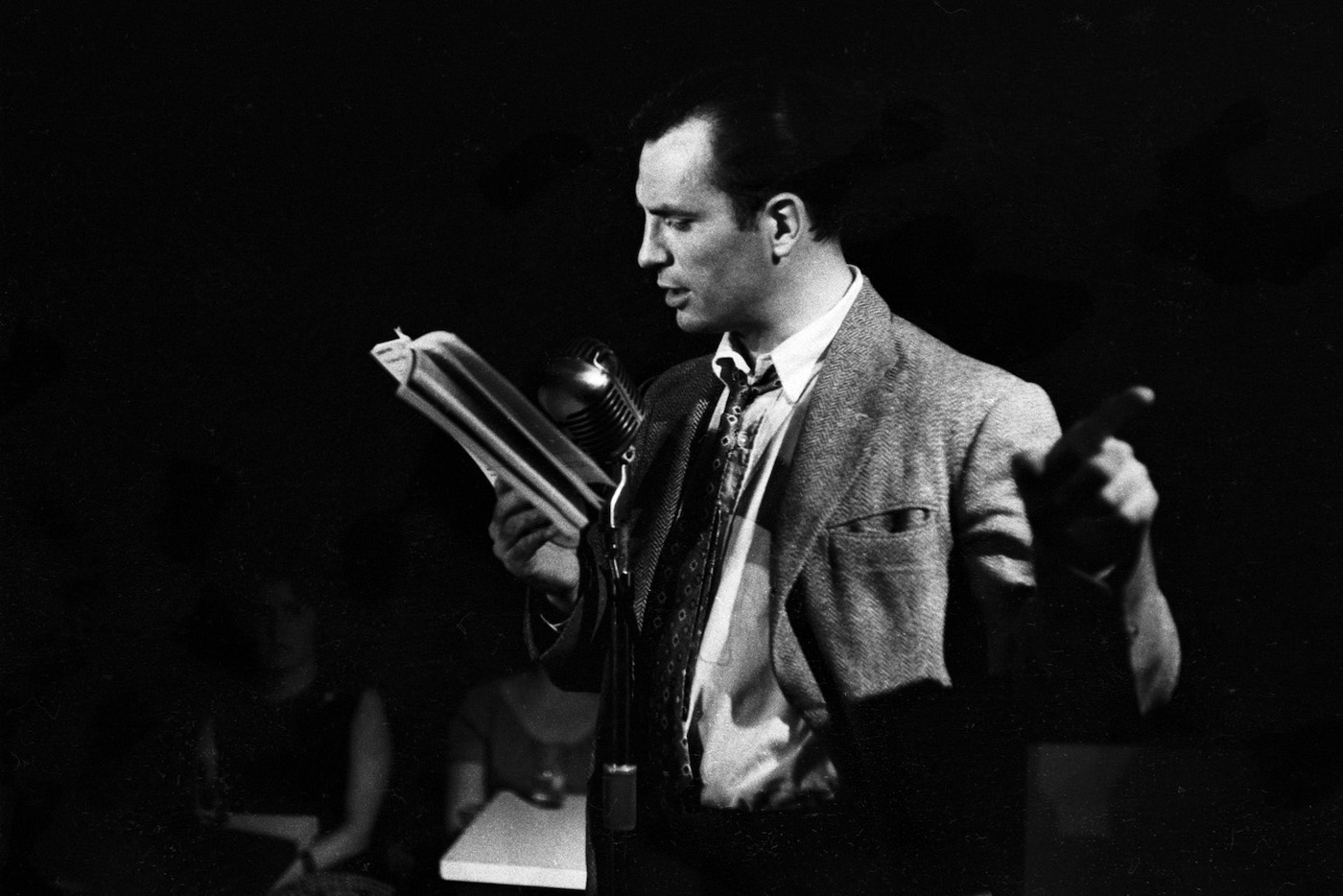

Lightning struck again in the mid-’50s when a group of wildly irreverent young writers from around the country trekked to San Francisco to be part of its creative environment. They included Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gary Snyder. The then middle-aged Rexroth took these rowdy iconoclasts under his wing. He was one of the first recognized writers and critics to support and promote what became known as the Beat Generation. Yanking poetry out of the staid halls of academia, Rexroth and his Beat cohorts often performed in dimly lit Tenderloin jazz cellars, passionately reciting their poetry on stage as shades-wearing jazzmen improvised floating sax lines in the background. TIME magazine anointed Rexroth as “Father of the Beats.”

Rexroth’s seminal influence continued into the 1960s, as he was one of the first important American writers to integrate into his works themes of Buddhism, pacifism, love of nature, and liberated sexuality. All were themes that would inspire and shape the hippie culture then beginning to blossom in Haight-Ashbury. However, by 1967 Rexroth, then 61, looked to new horizons. He felt the outlandishly extroverted, psychedelic hippie scene in San Francisco, which he admittedly had helped inspire, had become more limiting than liberating for him. After an inspiring trip to the serene Buddhist garden temples of Kyoto, Japan, Rexroth sought a new, quieter environment in which to pursue his interests in Eastern religion, contemplation, and nature. He took a meditation retreat to a Benedictine monastery – Mount Calvary – then high up on Gibraltar Road in Santa Barbara. Rexroth found new inspiration in the serenity of that quiet retreat, with its sweeping views of the Pacific below. While there he wrote A Song at the Winepresses. Pursuing themes of nature, East-West integration, and the inward journey, the poem blends scenes of Kyoto, Japan, with images of the arid Santa Ynez Mountains “looking out over fogbound Santa Barbara.”

Newly inspired by this retreat, Rexroth decided to leave the overheated urban scene of San Francisco and move to Santa Barbara. However, he did not relocate here to slip into quiet retirement. In addition to pursuing new themes in his writing, Rexroth wanted to pass on the benefit of his considerable erudition and unique insights in other ways than writing. Ed Loomis, then chairman of the English department at UC Santa Barbara, was a great admirer of Rexroth and gave him a teaching position at UCSB for the 1968-1969 academic year.

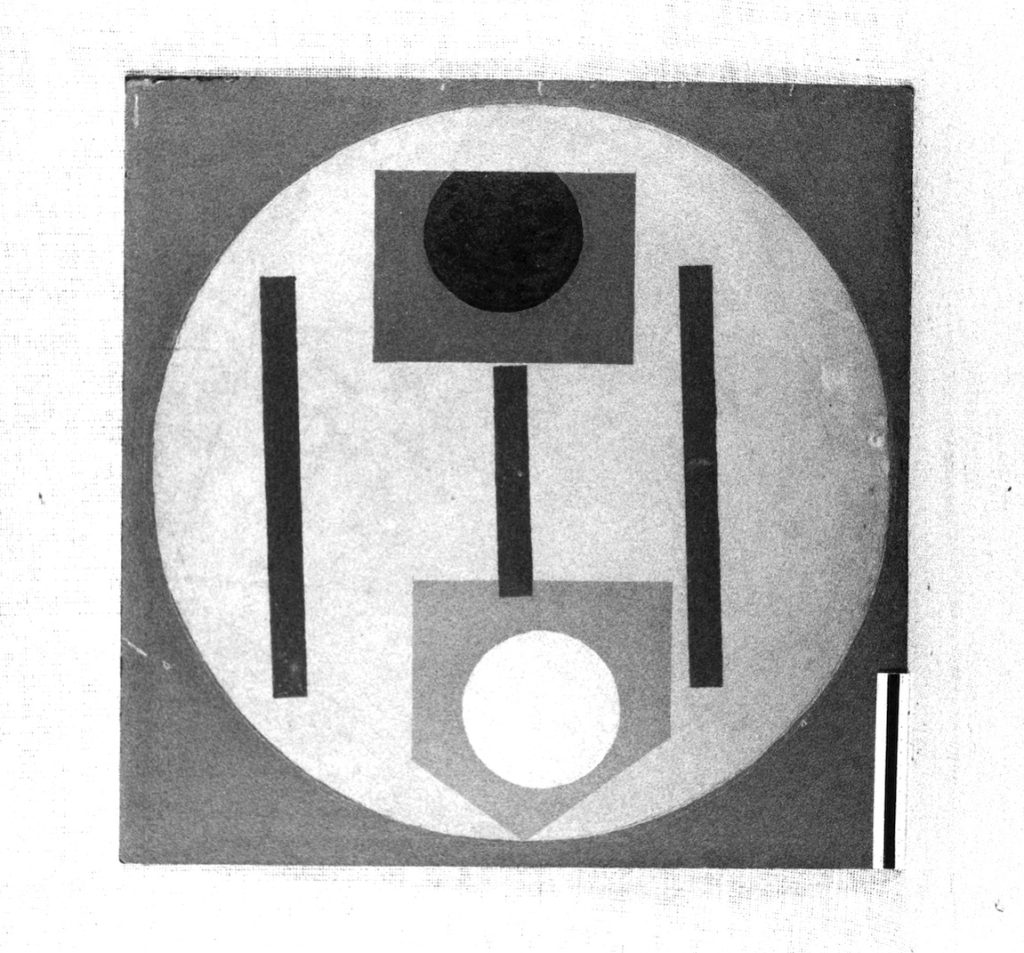

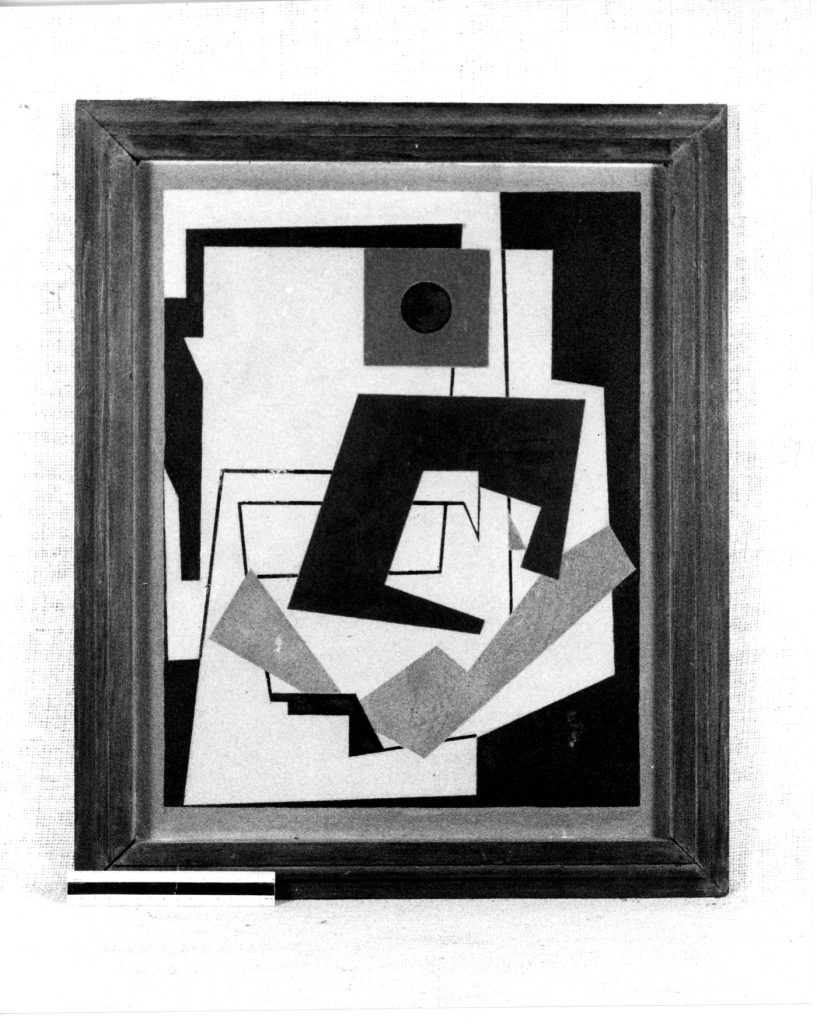

Rexroth moved into a house on Pimiento Lane in Montecito near Manning Park. His initial impressions of Santa Barbara life were not entirely positive, as he felt that other than among the college students, the then-prevailing social environment was less than completely friendly to his left-leaning politics. However, Rexroth eventually settled in, and in 1969 moved to another house nearby that ended up being where he would spend the rest of his life. Dower House on East Pepper Lane had been the servants’ quarters of a large estate that now faces Schoolhouse Road. No one had lived there for more than 40 years. With an 1895 house and separate cabin that Rexroth converted into a study, Rexroth transformed Dower House into not only a comfortable living space but a true cultural center. Rexroth installed in the house much of his library of more than 15,000 books, covered its walls with Edward Weston prints and Juan Gris paintings (as well as Rexroth’s own art), and filled its shelves and ledges with Tibetan statues and other exotica.

As befitted the free-spirited Rexroth, and the ’60s, his teaching methods at UCSB were unconventional, to say the least. Formally listed as Poetry and Song, his class was better known among UCSB students as Rexroth’s Night Club. Rather than just giving lectures and having his students regurgitate them back in tests, Rexroth’s class was interactive. Students were encouraged to make presentations of their “art,” which could be to recite a poem, play a flute, or perform a skit. Rexroth would comment on each presentation and then expound on some aspect of music, literature, philosophy, or religion. Although the class was unstructured, Rexroth was not without his standards. In a letter to a friend, he wrote that his initial impression of UCSB students was that they are “all stoned and they’re all illiterate.” But Rexroth and his students eventually warmed up to each other and he became quite a hit.

During the following academic year, rioting UCSB students looted and set fire to the local Bank of America, which stood on the site of today’s Embarcadero Hall. Unfazed by the campus disruption, Rexroth moved Poetry and Song to St. Mark’s Catholic Church in Isla Vista. Ed Loomis would later comment that he had found Rexroth’s time at UCSB to be a delight but acknowledged that it was regarded with “rage and shame” by the more conservative members of the English department.

In the meantime, Rexroth’s Dower House on Montecito’s East Pepper Lane – like Potrero Hill before it – had become the scene of lively cultural gatherings. A San Francisco friend bemoaned Rexroth’s move to Montecito: “You never know whom you might meet in his living room: LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Gary Snyder, Ken Kesey, or maybe [poets] Kazuko Shiraishi or Nanao Sakaki from Japan. When Kenneth moved to Santa Barbara and took a teaching position at the university, it was as if San Francisco had lost not just Kenneth, but the vital, dazzling world that belonged to him.” In addition to famous poets and artists, young aspiring writers, students, and random hippies began making pilgrimages to the now-sacred grounds of Pepper Lane. They would show up uninvited at Rexroth’s door hoping to be asked in, and often were, just so they could sit in the presence of the sage.

Despite the steady stream of visitors, Rexroth continued to produce new poetry while in Montecito, further developing his shift toward Eastern philosophy and aesthetic form that would characterize his later work. In the mid-’70s he wrote an extended poem, The Silver Swan, in which he intermixed Asian themes with images of coyotes in the hills above Montecito as he walked naked in the moonlight through his garden at Dower House.

Rexroth suffered a severe heart attack in late 1980, followed by a stroke in early 1981. But the then 76-year-old Rexroth continued to rage against the dying of the light. Later in 1981, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art mounted a major retrospective of Rexroth’s modernist paintings curated by Beatrice Farwell – “Kenneth Rexroth: Life at the Cultural Frontier.” In commenting on why Rexroth, who painted throughout his adult life, was not more widely recognized as a painter, Farwell’s gallery notes said Rexroth “has not sought to make a living by the art of painting. He has kept a large number of his paintings and pastels with him, the best of them on the walls of his home – presences manifesting the life of feeling at many periods in his history, and mementoes dedicated to a life of art.” Despite his ill health, Rexroth not only attended the museum exhibit’s opening, but also a celebration dinner that followed at one of his favorite local restaurants, Suishin, a sushi restaurant then on State Street.

Rexroth suffered another heart attack in June 1982, and this time did not survive. While he had not abandoned his long-held Buddhist beliefs, Rexroth had converted to Catholicism late in life. His funeral was held at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Catholic Church in Montecito. In a fittingly universalist ceremony, a Catholic priest delivered a eulogy, nuns from the Hindu-influenced Vedanta Temple in Montecito chanted in Sanskrit, a former student played music, and a friend recited from Rexroth’s poetry. Memorial services were also held in both Tokyo and Kyoto, where Rexroth was both well-known and highly respected.

While little remains of Rexroth’s presence in Montecito today, that was not his intent. Rexroth wanted the art-filled Dower House and its massive library to become a research center in his memory, a small-scale Huntington Library if you will. Unfortunately, it was not to be. Rexroth ended up bequeathing the house, library, and paintings to an order of Jesuit Catholic priests, who were to set up and administer the proposed center. However, the Jesuits decided that the project was more than they wanted to handle. In a cultural tragedy for Montecito, the house, art, and furniture were sold. Rexroth’s grand library was sold to a Japanese university, and today the “Rexroth East-West Collection” can be viewed at Kanda University of International Studies outside Tokyo, instead of at Pepper Lane.

The Mount Calvary monastery that first attracted Rexroth to Santa Barbara is also sadly no longer with us. It was engulfed in the 2008 Tea Fire, and the property was subsequently sold by the Benedictine monks. There remains, however, one small memorial to Rexroth in Montecito: his gravesite in the Santa Barbara Cemetery on Channel Drive (Sunset section, Block C, Grave 18). His grave is in a beautiful location overlooking the water and is well worth visiting on a sunny day. While all the surrounding gravestones face inward toward the approaching driveway, the gravestone of Rexroth – ever the iconoclast – faces out to sea.

Another well-known writer with a Santa Barbara connection, Pico Iyer, has said of Rexroth that he “is one of the lyrical and lucid inspirations of the past century, and also, ever more, one of the tragically overlooked figures in the ongoing project to bring America into contact with the larger world, through history and across the globe. He remains a national – and international – treasure, and the more people know him, the richer our world will be.” Perhaps one day Montecito will take inspiration from the Parisians’ Jardin du Luxembourg and place a memorial in Manning Park to Kenneth Rexroth.

You must be logged in to post a comment.