Old-Time Brewers in Santa Barbara

In Colonial Jamestown, having survived the starving time and learned how to work thanks to Captain John Smith’s edict of “no work, no food,” the male colonists wanted women. Not just for the delights of the fairer sex, but to share the work. Among her housewifery chores, a woman in Colonial America spun the wool, sewed the clothes, churned the butter, baked the bread, made the cheese, increased the population, and, perhaps most importantly, brewed the beer.

Brewing and distilling were extremely important in the 17th and 18th centuries in both the Old World and the New, because in most populated areas the water was foul and polluted. The brewing process killed the bacteria and infused the drink with nutrition. At the time, there was nothing more dangerous than a beaker of plain water.

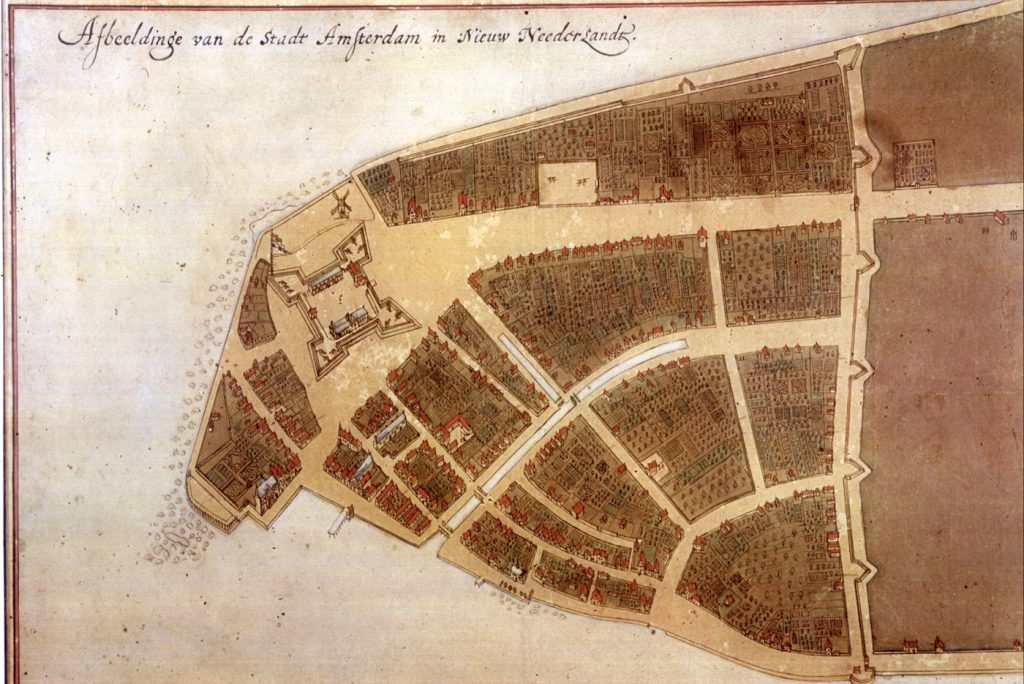

In the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, founded on Manhattan Island in 1625, brewing soon became a business managed by men. In 1660, New Amsterdam’s population of 2,000 could boast 23 breweries and taverns. Often these breweries would give or sell the byproduct of their product, the yeast needed to make bread, to the housewives.

As the American colonial population increased, it began to move west, and home brewing and town breweries went west as well. In Spanish and Mexican Santa Barbara, wine from local vineyards as well as aguardiente, which was fermented and distilled from a variety of sources, had been the norm. With the coming of the Americans, beer became increasingly popular.

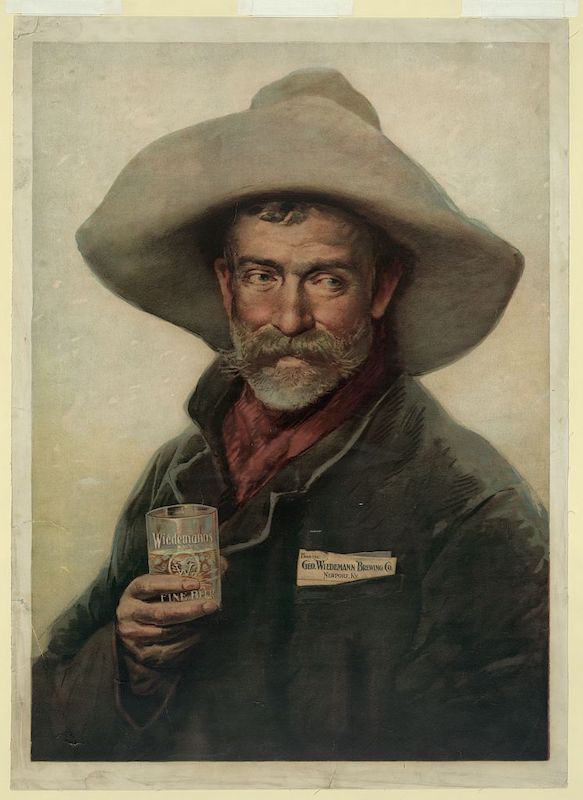

In 1867, there were 3,700 breweries in operation in America producing 6 million barrels of beer. In 1869, the 150,000 residents of San Francisco had a choice of beer from nine major and 14 smaller breweries spread out over the hills of the city by the bay. Some had a distinct British bill of fare as they proffered porter, stout, and ales, but German immigration to the United States over the previous 30 years had revolutionized the beer industry. Lagers and Weiss increased in popularity and were much lighter in color, alcohol, and flavor.

Nearly every small town, up and down the state (and for that matter the nation), had at least one brewery. Locally, Guadalupe, Nipomo, San Luis Obispo, Carpinteria, Ventura, and Santa Maria boasted at least one brewery each. In the 1870s, Santa Barbara, with a population of 2,000 thirsty souls, could boast at least two breweries, as well as nearly 25 saloons, many of which imported liquor and beer from San Francisco.

Breweries of Santa Barbara

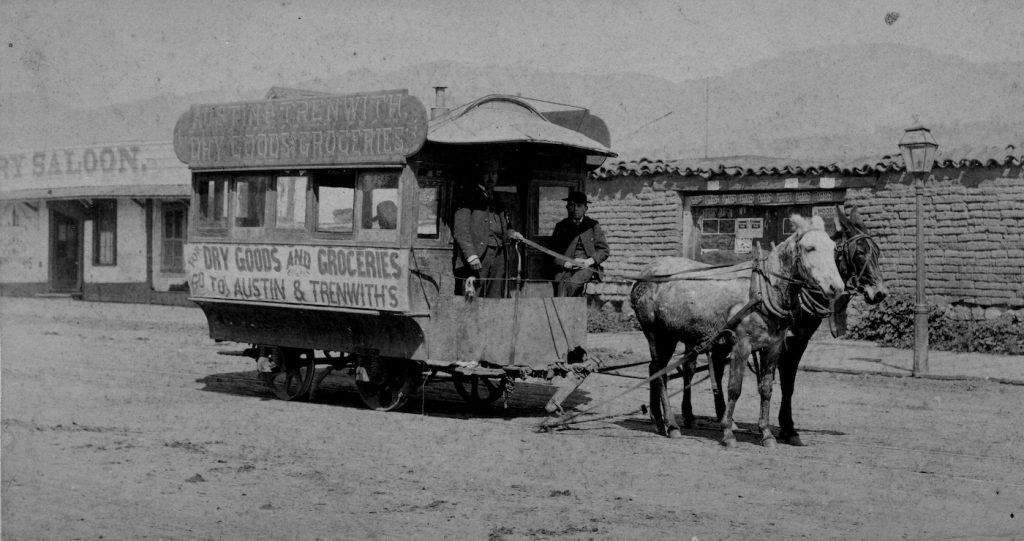

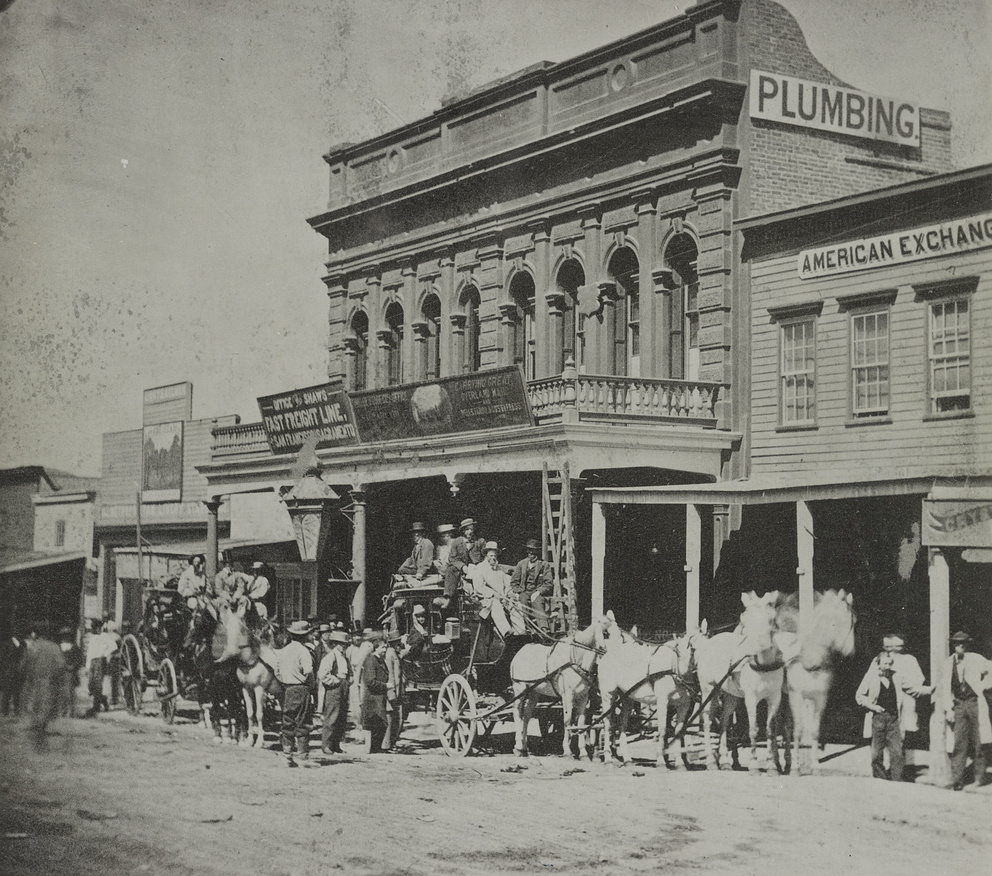

By 1869, Jose Lobero had purchased or opened the Brewery Saloon (to the left, behind the mule tram) which occupied a part of the Leyva Adobe on the corner of State and Canon Perdido streets. He soon had trouble with one of the Carrillos, possibly a former owner of the business, over indebtedness and the ownership of two pitchers. Carrillo tried to walk off with the pitchers, a scuffle ensued, and Carrillo stabbed the bartender, puncturing his lung. (It’s not clear whether the Brewery Saloon was actually a brewery or just sold imported brewery beer.)

The following year, a French brewer made his appearance in Santa Barbara. Named Michael Wurch, he opened a brewery on the corner of Cota and Anacapa streets. By 1874, he was doing such a brisk business that it attracted the likes of Charles Stuart, who robbed the till and was later caught. That same year, two of his patrons were convicted and fined $5 each for being drunk and disorderly.

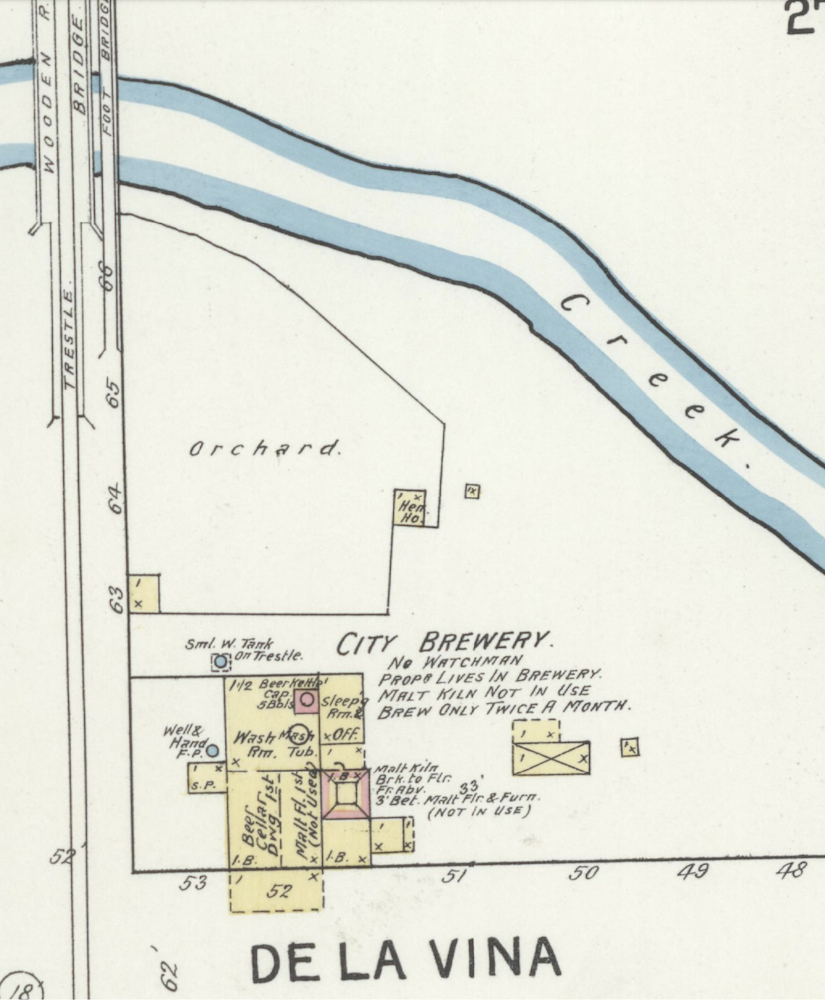

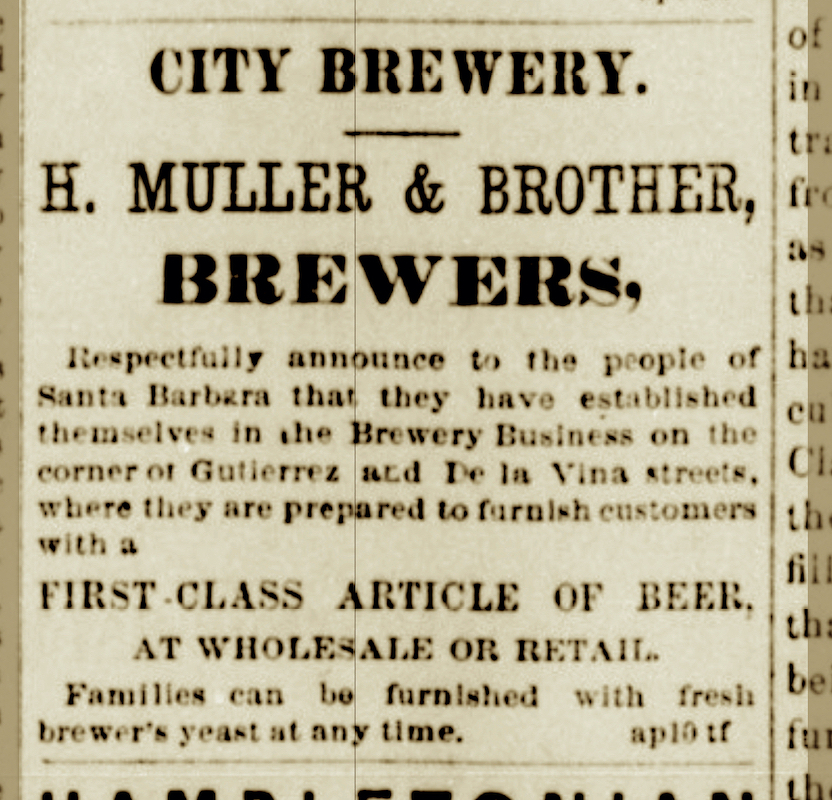

In 1875, Wurch found he had competition from German-born Henry R. Muller, who opened the City Brewery on the corner of Gutierrez and De la Vina streets. Wurch would soon go out of business when a mortgage foreclosure forced a sheriff’s sale for debts. The new Muller company promised a first-class article of beer and offered fresh brewer’s yeast to families who wanted it. Muller knew a thing or two about advertising and sent the Morning Press a sample of his manufacture. The newspaper announced that its beer drinkers declared it to be of good quality.

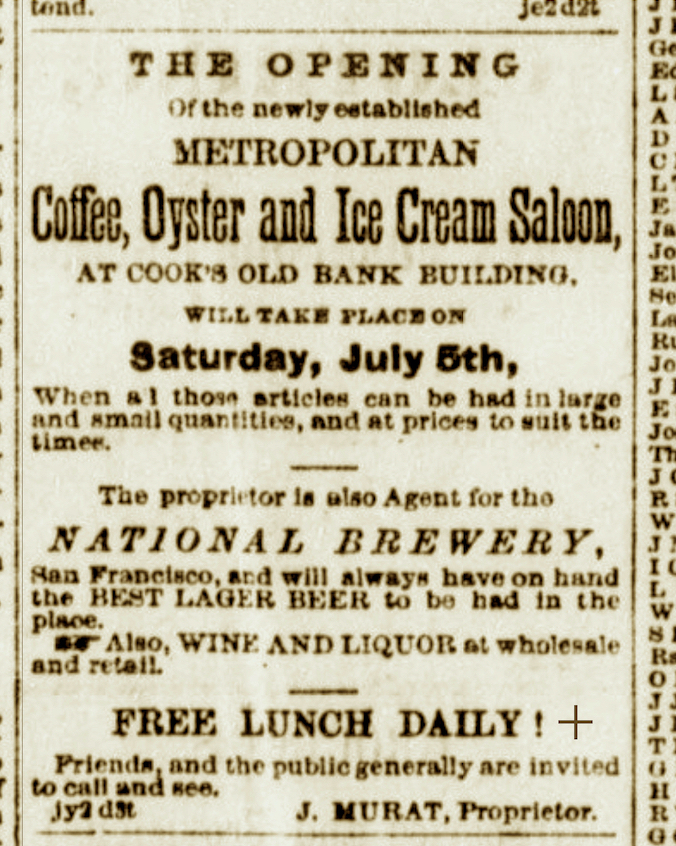

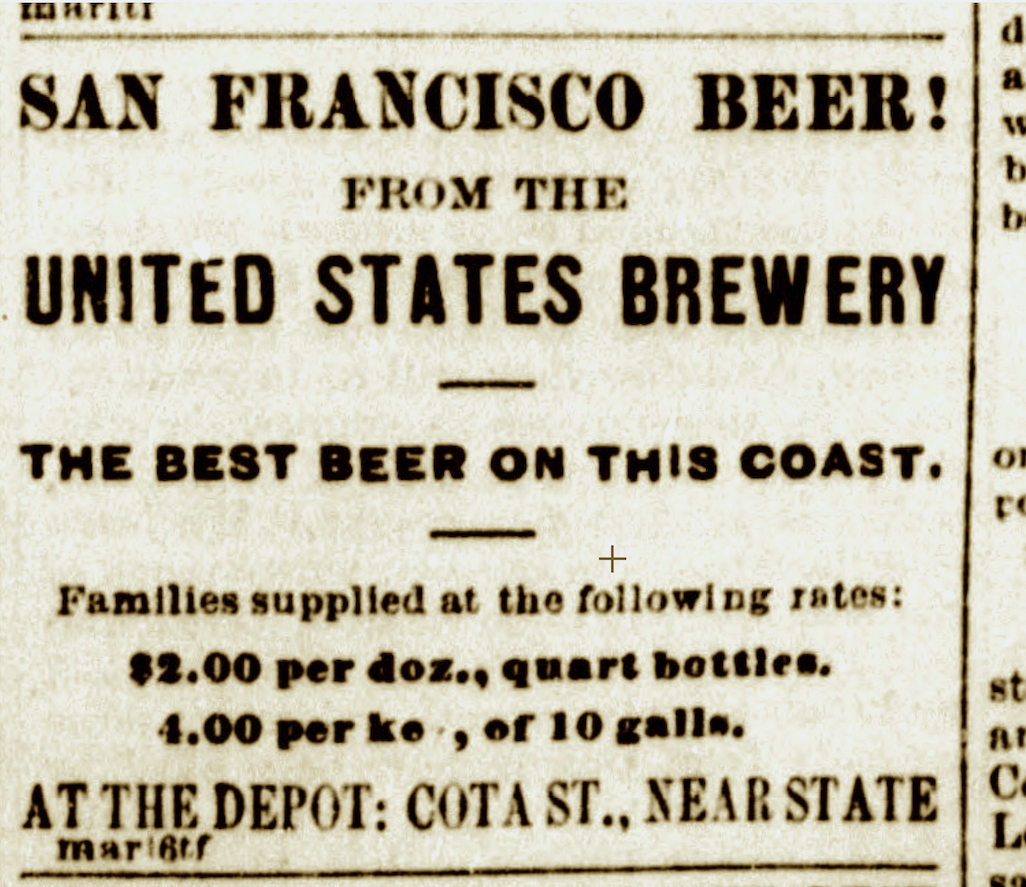

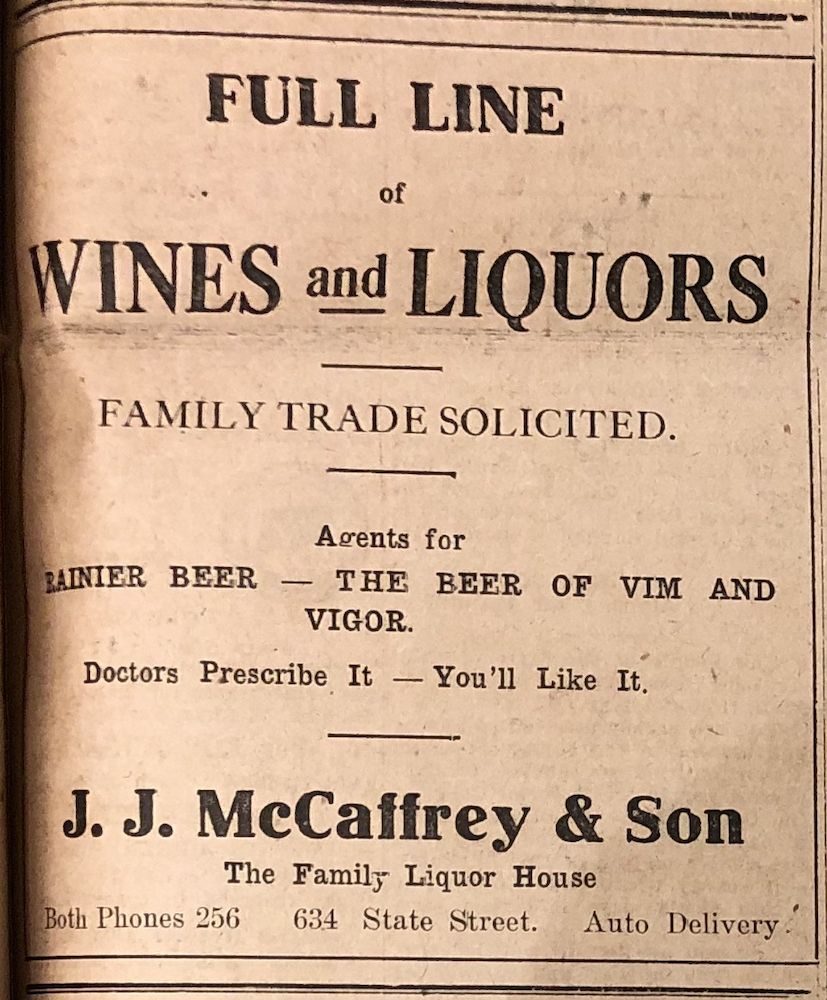

Nevertheless, Santa Barbara’s 25 saloons of the 1870s tended to import their beer from San Francisco. The Fashion Saloon on State Street, for instance, preferred the lager beer from San Francisco’s Humbolt Brewery. A satellite or franchise of San Francisco’s United States Brewery brought their beer to a depot on Cota Street near State. They then shipped empty kegs back to be refilled. It, too, was attractive to burglars, who broke in and stole 200 cigars and more than a dozen bottles of beer one night.

Brewer Herrmann Rudolph Muller

The Muller enterprise continued operating into the early years of the 20th century. A determined and adventurous man, Herrmann Rudolph Muller had immigrated to the United States in 1850 at age 25. Two years later, gold fever drew him to Hangtown (Placerville), but by then the “easy pickins” had disappeared. In 1853, therefore, he opened a tannery between the mining towns of Volcano and Jackson. Selling it four years later, he established a wholesale liquor and brewery business.

When word of the 1859 Comstock silver strike reached him, he pulled up stakes and headed for Virginia City, Nevada, where instead of mining, he put his money into yet another brewery. Mining, after all, was thirsty work. With the profits from the brewery, he purchased a hotel and other property in the area.

The end of the Civil War also saw the end of the nation’s dependence upon Virginia City silver. Muller, having little understanding of the peculiarities of Utah’s liquor laws, loaded up three wagons with liquor and headed for Salt Lake City. Needless to say, he was turned away, so he headed for the mining towns of Montana and prospected for gold. He was not terribly successful, so he returned to Virginia City to continue searching for a new vein of gold or silver. In 1867, he hit a bonanza and located a gold and silver mine in Pioche, Nevada, which he later sold for $30,000 and, restless as ever, moved his family to San Francisco. Herrmann’s final move came in 1875, when he came to Santa Barbara and bought the property on which to establish Santa Barbara’s City Brewery.

Prohibition and the Breweries

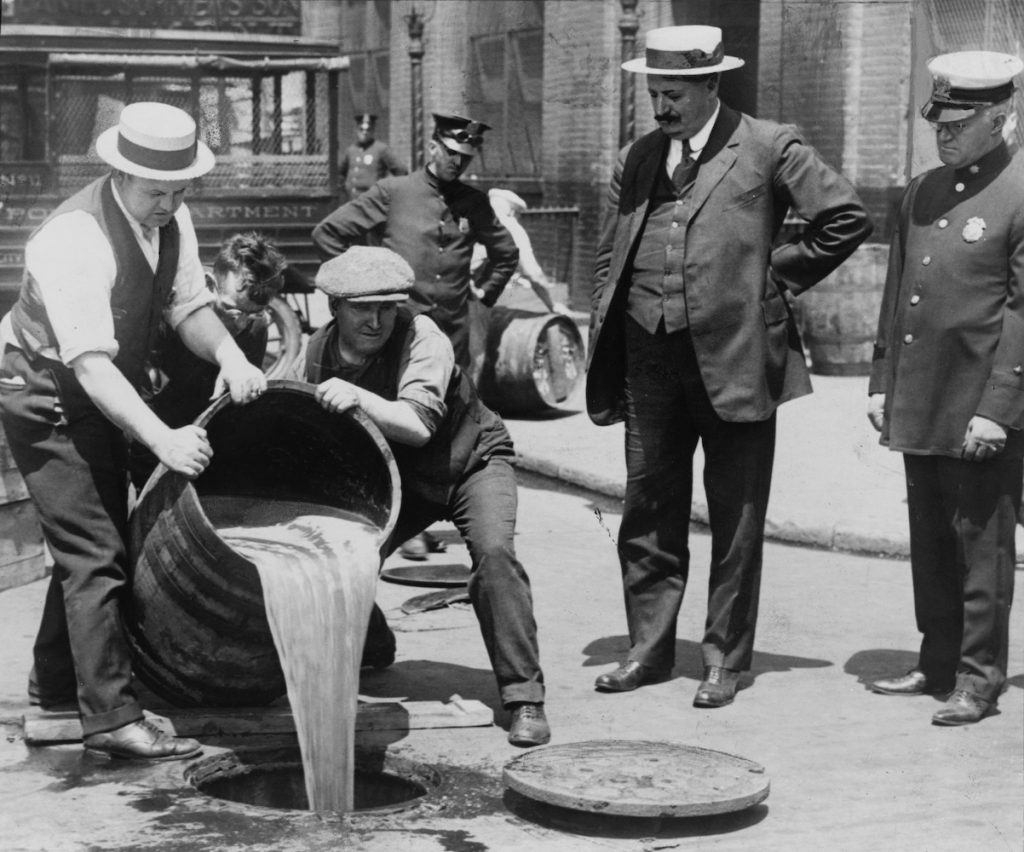

The forces of prohibition were at work long before the Volstead Act made the sale and consumption of all alcohol illegal in 1920. Local option laws, Sunday closings, the work of Santa Barbara’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, limited hours, licensing, and sundry other measures preceded the total ban. Since most of the violence and incarcerations in Santa Barbara were alcohol-related, there was obvious cause for concern.

In 1874, one woman became alarmed about the proximity of Wurch’s Brewery, which stood within 150 yards of the schoolhouse, from where children were exposed to vile language and witnessed violent and degrading behavior. Writing to the Morning Press, she exclaimed, “How can a Christian community rest while these things are carried on!? Intoxicating drink in all its forms of poison causes more misery, poverty, tax, and crime in our country than continued war.”

Events published in the paper that year and subsequent years seemed to support her cause for concern. When the State of California passed a local option law regarding saloons, both Santa Barbara and Montecito voted to go dry. Luckily (or unluckily), for the tippling population, the State Supreme Court struck down the local option law, and the saloon doors swung open again.

By 1875, the Morning Press, which was usually on the side of the “Wets” was compelled to write, “The United States Brewery [on Cota Street] seems to be the rendezvous of the entire fighting element of Santa Barbara, and lately this establishment has not only been having things pretty hot in its own spacious halls but has made times lively at the police court. It would be a good idea for the proper officers to consider this institution as a matter of profit and loss to the city, and, if the thing falls on the debit side, squelch it.”

In 1882, the press reported, “Henry Muller, an old pioneer, proprietor of the City Brewery, was stabbed by a disorderly character up from L.A. who had been travelling with a circus. He was drunk. Muller refused to serve him as he’d had enough, and ordered Murillo to leave and threw him out, at which point Murillo stabbed him near the heart, and Muller is in danger of dying.”

Nevertheless, the saloons remained open, and problems persisted. In 1883, the press reported that collective defective memory had saved one man the payment of a fine. The man had “made things very lively and interesting at the brewery [City Brewery] last night, breaking beer glasses and otherwise breaking the peaceful serenity of the place. When arraigned before the police judge this morning, some of the witnesses were unable to testify under oath what had occurred. They had taken in too much beer.”

In 1893, the Morning Press wrote, “The brewery, corner De la Vina and Gutierrez streets [City Brewery], of late has been a rendezvous for men of drinking proclivities, and those who reside in the vicinity complain, justly too, of the frequent brawls emanating from individuals who patronize the place. It was only the day before yesterday that a disreputable crowd of sheep shearers terrorized the whole neighborhood by their riotous conduct. This iniquitous inn should be closed, as it is a disgrace to our fair city.”

By 1907, many people had had enough. That year, the No-Saloon League came to town and gathered support for a campaign to close the saloons. Opponents claimed saloon closure would ruin business, be impossible to enforce, reduce tax revenues, violate individual liberty, and depopulate the city. Again, the citizens of Santa Barbara were asked to vote on the issue. Nevertheless, this time the “Drys” lost by 325 votes.

Prohibition and then…

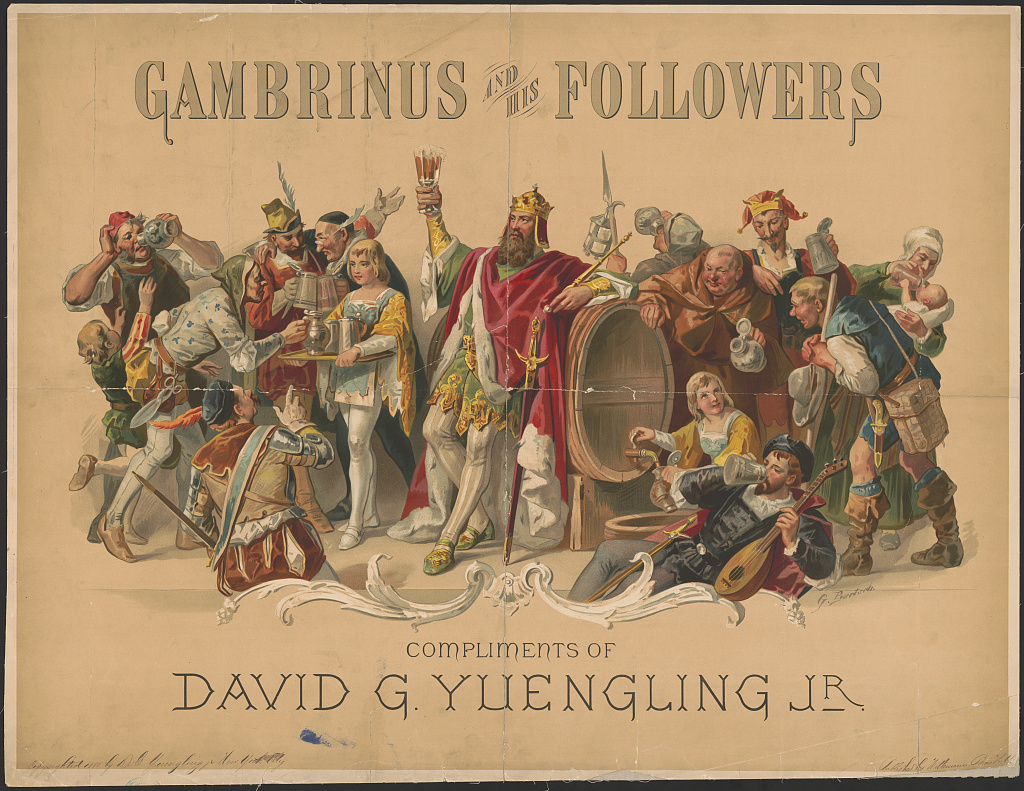

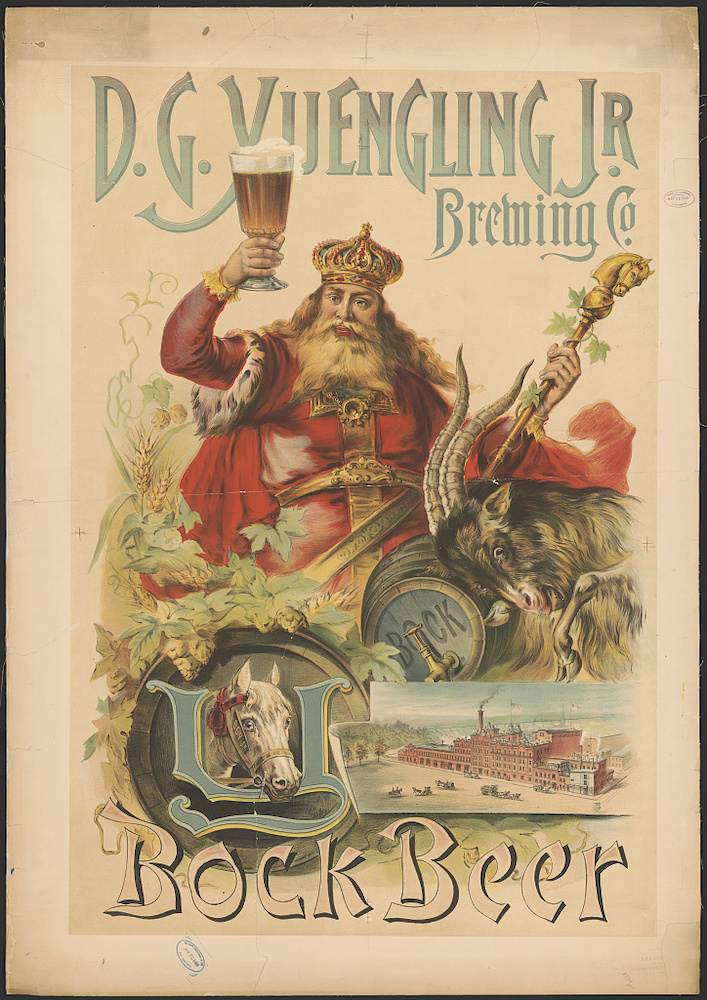

Santa Barbara had 13 more years of enjoying, what a Morning Press editor in 1878 had deemed “the innocent and refreshing beverage fabled to have been first brewed by that far-famed old Teuton, Gambrinus.” Nevertheless, in 1919, the Volstead Act not only closed the saloons, but made it illegal to make, sell, or drink all liquor, including beer.

When it was all over in December 1933, only those breweries that had been able to adapt their manufacturing during the dry years were still in business. Of those, the Yuengling family’s Eagle Brewery of Pittsburg, Penn., had survived by producing near beers and opening a dairy that produced ice cream. To celebrate their reopening as a brewery, they delivered a truckload of beer to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Established in 1829, Yuengling is the oldest continuously operating brewery in the United States.

Small, individual breweries, however, had pretty much disappeared, though many of the large manufacturers resurfaced and prospered. Then, in the late 1970s, the first microbreweries were established, leading to today’s brewpub and craft brewing industry which appeals to a decidedly different clientele than the brawling, alcoholic rowdies of the terrible “good old days.”

Sources

Contemporary Morning Press articles; newspapers.com; ancestry.com; beerhistory.com; Martin H. Stack, “A Concise History of America’s Brewing Industry”; Historical and Biographical Record of Southern California: Containing a History of Southern California from Its Earliest Settlement to the Opening Year of the Twentieth Century by James Miller Guinn, 1902; Yuengling.com; Santa Barbara City Directories; Stephanie Castellano, “The Brides ‘Imported’ to Colonial America for Their Brewing Skills,” 2021.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.