A Seat at the Table

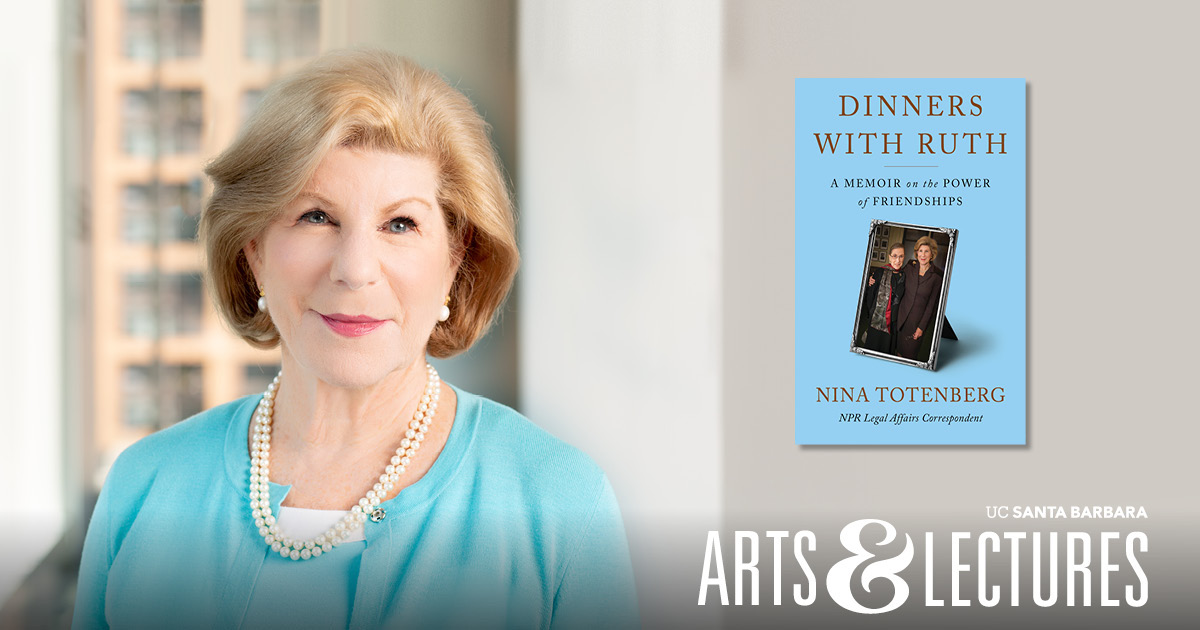

Anita Hill never wanted to testify before the Senate Judiciary committee. In fact, despite a stellar academic record, you probably would not know the name Anita Hill if not for veteran NPR Legal Affairs Correspondent Nina Totenberg. The same way you wouldn’t know the Watergate Hotel, if not for Woodward and Bernstein. How it came to be that Hill overcame her reluctance to testify is just one of the many eye-opening anecdotes in Totenberg’s recently released New York Times best-selling book, Dinners with Ruth.

Known by many in D.C. circles for her legendary scoops, Totenberg, whose reporting has focused primarily on the activities and politics of the Supreme Court over five decades, is perhaps most famous for breaking the story and conducting the interview that resulted in Hill, the law professor who accused Justice Clarence Thomas of sexually harassing her, in testifying at Thomas’s confirmation hearing.

But Totenberg is not just an “ordinary” tenacious, crusading reporter. In her book, she recounts how even after jumping through flaming hoops to obtain Hill’s FBI affidavit – a prerequisite for Hill agreeing to an interview with Totenberg – Totenberg sat on the Hill interview until she was convinced that both she and Hill understood the enormity of how this would likely resonate in both of their lives. Which it did.

If it hadn’t been for Totenberg’s landmark interview with Hill, the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by then Senator Joe Biden, would have succeeded in burying the FBI-obtained evidence of Justice Thomas’s behavior. Apparently, Biden, at that time (and the committee as a whole), never got that sexual harassment was a serious charge. And according to Totenberg, Thomas’s supporters were good with that. “One of Orrin Hatch’s top aides told me, ‘We think Biden did just fine,’” Totenberg writes.

In Dinners with Ruth, Totenberg weaves a story that is equal parts a personal and professional memoir, and tracks a nearly-50-year friendship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, which began decades before Ginsburg ascended to the Supreme Court and grew deeper as each supported the other through the most extreme experiences of their lives. The book explores the rise of two women who began their careers decades before the #MeToo movement, and which exposed the gauntlet of misogynistic landmines women have had to navigate in order to climb the professional ladder in… well… anything. It’s a story of two courageous and indefatigable women whose friendship grew as each pried open doors for themselves; and for the women who would follow in their paths.

The book also explores Totenberg’s insights into the Supreme Court itself, its game and its players, over those same five decades.

But Dinners with Ruth is fundamentally a story about the life-sustaining power of friendship. Totenberg manages to penetrate worlds that are notoriously impassable, like the personal lives of Supreme Court Justices and members of Congress. And she does so, in part, through an institution that today in D.C. amongst political adversaries, verges on extinction – namely, friendship.

But even as the consummate insider, Totenberg remains unrelentingly discreet, not just about her insights into Justice Ginsburg, but about other Supreme Court Justices with whom she built deep friendships, high-ranking politicians, her longtime NPR colleagues, and her own family.

What struck me most about the book was Totenberg’s generosity and fair-mindedness, even towards those of whom she clearly did not think highly; or, more notably, did not think highly of her. A good example being her once tempestuous relationship with Senator Alan Simpson (R., WY) that played out on national television in 1991 in a heated clash on Nightline, and then continued outside ABC News headquarters in a row over Totenberg’s interview with Anita Hill, with Simpson assailing Totenberg’s methods and ethics and accusing the dogged NPR reporter of having “ruined Anita Hill’s life.” Today, Totenberg and Simpson are friends.

I had the opportunity to speak with Nina Totenberg about her must-read tell-just-enough book – part personal memoir, part historical non-fiction – in which Totenberg offers us a seat at the table with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her supportive, jovial husband Marty, Supreme Court Justices Antonin Scalia and William Brennan, Lewis Powell, NPR’s Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer, and a whole host of other legendary judicial and political figures with whom Totenberg regularly dined; but on whom she never dined out.

On Tuesday, February 7 at 7:30 pm, Nina Totenberg will speak at the Granada Theatre as part of UCSB Arts & Lectures Series’ Thematic Learning Initiative.

Do yourself a favor: read the book. And attend.

Gwyn Lurie (GL): Why did you write this book? Which by the way, I loved.

Nina Totenberg (NT): Well, it wasn’t my idea is the truth. Simon & Schuster and other publishers approached me about writing a book after Ruth died. And I said no to everybody, including Simon & Schuster. I didn’t keep a journal. I probably forgot more stories than I remembered about our friendship, and I didn’t want to write that book anyway. And this wasn’t the first time I’d been asked to write about almost anything I wanted about the Supreme Court, and I always said no because I have a day job… At one point, I ran a list of all my stories at NPR and it was well over 10,000. So just reading them would take too long.

Eventually I agreed to have a Zoom call with the head of Simon & Schuster. And I said what I’d said to everybody before. I don’t want to write a book. It’s too long, it’s too daunting. I have no idea how I would frame it. Forget about it. And he said, Well, I have an idea for a book you should write. And about this time, my husband wandered in and I said, sit down David. And the publisher at Simon & Schuster said, I think you should write a book obviously about Ruth, but about all of your friendships, your female friendships and some of your male friendships too, because you represent, and the women of your generation represent, people who were not by and large trying to crash through a glass ceiling; you were trying to get a foot in the door. And that’s absolutely true.

And I thought that was a pretty good idea, but I still was not the least bit sold, because I couldn’t see how I would do it. But at least it was a tree you could hang things on, so to speak. And I had a whole bunch of other objections…

But the very last and most important reason I didn’t want to write a book is that my husband didn’t want me to write a book because I worked too hard as it is. He works less hard than he used to, and he didn’t want more time snatched away from us. And I literally had my mouth open to say No, and David says, “I think you should write this book.”

GL: Your book deals a lot with the evolution of women in media, and the workplace generally. And the breaking of glass ceilings and the prices paid. We’ve come some distance since F. Lee Bailey called a bench conference and complained to the judge about your attire and how it was distracting the jury.

NT: Really, I think he was teasing me. I think he was just trying to break things up or something because I really didn’t take it then that he meant it seriously.

GL: But you couldn’t even get away with such a joke today.

NT: Right. And that’s one of my problems with the #MeToo Movement is that it really does have no sense of humor, none. And I agree, the line is a very difficult one to set, but it is there, and you don’t want to be in a humorless world where everybody has to be afraid of what they’re going to say all the time. And that’s, I think, where we are a lot today, and it’s too bad. I suppose it’s a place we needed to get to, but I hope at some point we get beyond it.

GL: It’s sort of a double-edged sword. I agree that we’ve lost some of our humor; and when men and women work together, they’re going to have different kinds of relationships than when women work together or when men work together. But where do you think we are today in terms of this non-linear journey of women being empowered in the workplace, and not fearing that moment, as you described, when your boss asks you out and you have that sinking feeling that either I say yes and betray myself, or I say no and offend my boss?

NT: Right. So, I think we’re well beyond that, but I do think that the best of men, not the worst of them, are often afraid of having serious professional relationships with us because they don’t want to be misunderstood, and I think that’s a terrible loss. Obviously, women walk the ladder upward, upward, upward, so they run huge enterprises, certainly in the media world. But for young women, I think they do have to suck it up a little bit. And the workplace is not meant to be your mother. It’s a workplace and you have to treat it that way and work hard and show up. I mean, people ask me all the time – how did you make all these friends? – whether it’s Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer or Ted Olson and Justice Powell. I met them through work. And if you stay home in your hovel, you will never meet people and make friends with them.

GL: You once asked Justice Ginsburg if she’d ever been harassed?

NT: Yes. I asked her and it was at Sundance when the movie RBG was premiering, and I did this interview of her on stage, and we were introduced by Robert Redford. And because the #MeToo Movement had just burst onto the scenes, and I told her I was going to ask her. Because it worked better than springing it on her, in which case she just didn’t answer very well.

So I said, have you ever been sexually harassed? And she said, Well, Nina, nobody of your age or mine has not been sexually harassed, let’s get real here. And I said, can you give us an example? She said, Well, when I was at Cornell, I had to take, I don’t remember whether it was chemistry or biology – let’s just say biology for the sake of argument, and she had a full scholarship – and she said, I was very worried about it because it was unlike all my other courses. I had difficulty with it. And so, I went to see the professor to see if there was anything I could do to be sure that I did well on the exam. And he said that he would give me a practice exam. So he gives her this practice exam, and two days later she goes to take the exam and it’s the same exam. And she said, I knew what he wanted.

So I’m sitting there thinking, what would I have done? I probably would’ve run away and never seen him again. I said, So what did you do? She’s 17 years old at the time. She said, I went to see him. And I said, “How dare you? How dare you?”

[Totenberg shakes her fist to reflect Ginsburg’s indignation.]

GL: In your book you refer to “the Old Girls Club at NPR,” and you write a lot about your friendship with Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer. And I love the example of you going to bat for Mara Liasson to get her job. Why do you think that women so often get a bad rap on supporting each other? Do you think it’s justified?

NT: No, I don’t think it’s justified at all. I think that in the years when there were very few women, at least in the workforce, other than the blue collar and pink collar workforce, if you’re talking about professional life, whether it’s lawyers, doctors, physicists, journalists, whatever, there were so few of us. I mean, we were as scarce as hen’s teeth. I think that some women did basically feel there were two versions of this. That’s in every minority group, although we are, I always point out, a majority group, we were just an acute minority.

So that’s one thing. And then, I do think that sometimes women felt that they had to act like they were one of the boys instead of one of the girls. And I think once there got to be a decent number of women in the workforce, that changed. When I came to NPR, every place I ever worked, I was either the only woman or there was one other woman. And when I came to NPR, suddenly there were all these women. Linda [Wertheimer] was there, we then got Cokie [Roberts] hired, Susan Stamberg was there already. I mean, most of the reporters were women for the simple reason they paid so little, no man would’ve worked for that money, but it meant that we had the Old Girls’ Network. We had a coterie of friends and fellow professionals who were experiencing the same things we were, whether it was a husband being impossible, or a child who’s on the phone yelling that she wants to go to Janie’s house. Or you would be dealing with a boss, who was not really sexually harassing any of us because they didn’t dare, I don’t think. Because we were a network, we were the Old Girls’ Network, and you weren’t just going to be taking on me or Cokie or Linda or Susan. You’d be taking all of us on if you did something that stupid.

GL: You broke the Anita Hill story on NPR, which caused you and Professor Hill problems for a long time. But you also changed history in that this was one of the first times discussed how a public figure comported himself privately, became a public discussion as an indication of their professional fitness. But unfortunately, as you write in the book, the truth-seeking role was lost in the shuffle of that process. Given that no one ever questioned the veracity of your story about Hill being harassed by Thomas, why do you think these charges were never resurrected again in any serious way?

NT: Well, I always thought that my story was not just that she alleged that Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her when she worked for him, but that the Judiciary Committee actually knew that, and never really did anything about it and didn’t follow up in any serious way. It got the FBI to interview her and sign an affidavit, and that was the end… Which we saw replicated in the Kavanaugh hearings.

GL: How did you feel watching the Kavanaugh hearings and Professor Ford’s testimony?

NT: I felt like a seer; and the day that Christine Blasey Ford testified, everybody said, Oh, it’s over. And I said on the air, no, it’s not. That’s what people thought in the Thomas hearings, and you haven’t heard his side yet and you haven’t seen what politicians are willing to do in a fight like this. And so, we saw it replicated, and I think it’s been very harmful for Justice Kavanaugh, who I like and generally respect personally.

But because there was no proper investigation and now there’s a documentary that brings forth new evidence and because the Democrats mishandled the allegation to begin with, it could never be explored privately behind closed doors. I mean, if I were God and I were running a judiciary committee hearing and somebody made a really important nasty personal allegation about a nominee, I would have my own investigators, not just the FBI, go out and check up on it. And I would not have a huge hearing. I would want to find out and I would want the other party to be in on the investigation so that you could actually figure out what happened, or to the best of your ability, figure out what happened.

GL: Do you think Kavanaugh should not have been confirmed?

NT: I’ve never said that. I don’t plan to say that.

GL: You just think it should have been fully investigated and looked at honestly.

NT: Yes. And I thought the same thing with the Thomas nomination. There were other witnesses that were not heard, in part because the Democrats didn’t want to prolong it, and in part because I think some of them thought that those witnesses were not fully credible. But if that’s the case, then let’s know that. Let’s not just try to cover it over and have a big fight over it.

GL: Well, politics have never been a gentle sport.

NT: No.

GL: But things feel different now. And you talk about how it’s hard to believe now that there was a time that senators would cross party lines over judicial nominations when they thought a nominee was somehow unqualified to serve. This doesn’t happen today. What are your thoughts on the current confirmation process and what impact do you think it’s having on the court?

NT: It’s totally broken as a process, the confirmation process. The Democrats are now engaging in what Donald Trump perfected, which is to ram through lower court judgeships as quickly as you can, and I actually can’t think of one Biden nominee who’s actually had to withdraw. There were a couple of Trump nominees who became so embarrassing that they had to withdraw. But it’s not good. I mean, I’m a valid person in the mushy middle, and I think there’s a great deal to be said for being in the mushy middle. I’m fine with having people on the extreme right and the extreme left sometimes, but not all the time. And it really is, I think, very damaging to a society to not encourage people to be respectful and somewhat more balanced in their views and not just always assume they’re right.

GL: Historically, a number of Justices have been political surprises, either more or less conservative than expected. Justice Blackmun and Justice Souter are two more recent examples. Is this still possible in today’s more polarized environment?

NT: I think it’s very unlikely, because if you are our president and the opposite party is in control of the Senate, Mitch McConnell has made it so that you have a very hard time getting anybody confirmed to a seat on the Supreme Court, period. I mean, in the case of Merrick Garland, who Republicans for years said would’ve been their choice as a democratic nominee, I think they stalled for 10 months, and he never got a hearing… You have the real possibility, if you’re a Republican president with a Democratic Senate, or vice versa, of getting nobody through. And then if you do have control of the Senate, you get what the outer edge of your party prefers as the nominee. And it is possible that people change over time, really change their views, but I think the Federalist Society has perfected the idea of celebrating people who are more and more and more conservative, and I expect similar things to happen on the left.

GL: So what’s happened is what Justice Ginsburg and you agreed would happen if the court was packed, which is that it’s become too politicized – the process, and the court itself. Would you agree with that?

NT: There’s been quite a discussion about this among court members in their public speeches, with the Trump appointees saying, “We’re not hacks.” Amy Coney Barrett famously said that “We’re not hacks.” But because there is no center left on the court and there is a six to three ultra conservative majority, it means that at least half – and often more – of the country doesn’t believe that that six to three majority is doing anything other than reflecting a political view. Now, I think in some cases that is really not true, but it’s very hard to persuade people of that when the court is systematically dismantling a lot of precedents, the most prominent, of course, being Roe v. Wade, but there are others.

GL: And that goes to the whole question of public trust, right?

NT: Right. I think the Chief Justice to some extent does clearly understand that and is trying to sort of keep the court from going off the cliff and losing its credibility, but they don’t need his vote and they are acting without him in some of the most controversial cases, although he joins them in most of them.

GL: Do you think Justice Ginsburg regretted not stepping down when President Obama had hinted that she should consider doing so?

NT: I don’t actually know. I think that she really believed that she could tough it out. I don’t think she ever believed that Donald Trump would become president. That was clear. And I think that once he was, she felt it was her duty to tough it out and not give him another vacancy. And she came very close. She came within weeks of doing that, but she didn’t make it. She rolled the dice and she lost, and there’s just no question about that. And it is, I think, probably the most serious mark on her otherwise completely stellar service, that she didn’t realize what Obama realized, which is that she couldn’t… She did say to me at one point, quite near the end of her life, she said, “You know I can’t live forever.” But that was in a discussion about what if Trump were reelected? And she said, “I probably can’t live forever.” But Supreme Court Justices have political views, as we see quite clearly, but they really don’t know much about politics. And she thought she knew better than the president knew, and she was wrong.

GL: Do you still enjoy your work given the state of the media and politics today?

NT: I completely enjoy my work. What a great story. The court is tearing up the turf. It’s losing its credibility by doing that in some respects. It’s gratifying the right, and I have a beat that often was not all that interesting to many people, except occasionally. That’s not true anymore. It’s a great story. I’m a reporter and this is a great story. What’s not to like?

GL: On a more personal level, you and Justice Ginsburg shared a lot. You shared great senses of humor, you shared an appreciation for each other’s journeys, but you also shared a Jewish heritage. In a way, you’re the child of a Holocaust survivor. I mean, your father got out of Europe in 1935 because of his art, but you still have lost many relatives. Has that impacted your worldview?

(Totenberg’s father, Roman Totenberg, was a virtuoso violinist and teacher who made his debut as a soloist with the Warsaw Philharmonic at age 11 and performed and taught until his death in his mid 90s.)

NT: Well, I think it has. I know a lot about the history of World War II and I’ve read deeply about it. And I think I had always thought that it couldn’t happen here, and I don’t think that anymore. I am alarmed by the rise of anti-Semitism, along with other kinds of racism and white nationalism. I grew up feeling the Holocaust very personally, and until I was well into my 20s, I would have a recurring nightmare in which the Gestapo came to get me and that I hid. It was always the same. I think I must have started having this dream in college; I ran to the laundry room, and I hid in a washing machine. And in the dream, these soldiers come down and they start opening, bang, bang, bang! And then something happens where their commander says, Come on, we’ve got to go. And they’re about to get to me and I wake up.

So, I’m not a particularly religious person, but this is not something that is antiseptic in any way to me. It is very personal. And it’s not just the massacres at synagogues, it’s the kind of casual anti-Semitic things that are written on overpasses. I never used to see that, and it alarms me. I’m with Joe Biden on this. It’s not the country we are or should want to be.

GL: You’ve become close with many Supreme Court Justices including Powell, Brennan, Scalia, and of course, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. And while, as you write, getting to know the Justices pierced a veil of secrecy that pervades the place, do you think that these close friendships ever impaired your ability to report objectively or fairly?

NT: No, I don’t think it ever impaired my ability to report fairly, or as objectively as I could anyway, as one is reasonably able to do. And the reason is that I didn’t find out from them secrets from behind the scenes of what was going on in a given case. No Justice would ever tell me that. And if I had asked, that Justice would not have been my friend. But what I did learn from them is who they were, how they got to the beliefs that they had, and what sort of a person they were. Both the background stories and what makes them tick and how and why they got an idea.

I tell a story in the book that I learned from Justice Powell after he’d retired; I would go to lunch with him once every month or two. And I asked him one day why he was such a staunch defender of abortion rights, because it seemed to me kind of contradictory that a man born and raised in the early part of the 20th century and who lived in Richmond, Virginia, would come to what many viewed as a fairly radical view, other than the fact that he had daughters.

And he told me that the story, which I relay in the book, is that when he was a relatively young lawyer, probably in his 30s or early 40s, he had a messenger, a boy, he called him. And he was a boy, he was 18. And he called him one day at home and he said, Mr. Powell, I’m in trouble. Would you come? And so Powell drove over to what was then the Black section of Richmond and found that his messenger was there with the woman that he lived with who was “an older woman.” She was probably in her early 20s, and she had aborted herself and bled to death. And he ultimately persuaded the local prosecutor not to bring charges against his messenger because, as he put it, the woman made her choice, she did the abortion, and it was a coat hanger abortion. And she was an older woman, and he was under her influence. And then he looked at me and he said, “After that, Nina, I always thought, this is not the business of the government.”

Some would say it’s an almost Libertarian view that this is not the business of the government; but for people who are very strongly opposed to abortion, it didn’t consider the life of the child. But he thought that the damage done was so much more important, and I think it’s fair to say he did not think a fetus was a child yet.

GL: In the epilogue of your book, you say that if Ruth were alive, she would be white-faced with fury at Justice Alito’s attempt to enlist her nuanced legal writing in a New York University Law Review article 30 years ago to support his argument in the Dobbs decision. Do you think he would’ve dared to do that if she had been alive?

NT: No, and the reason is she would’ve taken his skin off. And I actually thought that reference would be dropped. I ran into one of her former clerks after the Dobbs leak in an airport, and I said, Did you see he’s enlisting your former boss? And he said, Oh, that’ll be gone by the time it comes out. And under normal circumstances, it probably would’ve been, because the liberal members of the court would take such umbrage at it and maybe even Kavanaugh would’ve. But I think it’s fairly clear not who leaked this document but what kind of a person and why, and I think it was somebody who wanted to freeze the status quo at the court and make sure that the Chief Justice did not succeed in getting Kavanaugh to join him in a more modest opinion that would’ve upheld the Mississippi law banning abortions after 15 weeks but left the right to abortion in place, at least for the time being.

GL: Do you have any theories of who the leaker was?

NT: No, I have no idea who it was. I just think it was somebody on the conservative side, and I think that’s the general consensus of those of us who cover the court, that that was the purpose, and it succeeded. I’ve been through many Justice’s papers in the Library of Congress, and you see the progression of an opinion as it goes through the editing process and the collegial process of other members of the court putting their stamp on it. And almost always, the most objectionable things are dropped in order to keep as many people under one tent as they can. But in this case, virtually nothing changed from the February draft to the release of the opinion in June, and that says to me a great deal. The leaker succeeded in freezing the status quo and the normal process of softening the edges a bit just never happened.

GL: You write that you agreed with Justice Ginsburg’s criticism of the ‘72 Roe decision, that it wasn’t necessarily the best case to use to establish abortion rights. And it was a view for which she took a lot of heat, right? Can you explain that?

NT: Yes. Well, Ruth thought that rather than just a right to privacy, it would be better to have been based on the notion of women being guaranteed equal protection of the law, and that they would not be treated differently from men under the 14th Amendment when it comes to making decisions about whether to bear a child, whether to have a child. And I think she felt very strongly that those decisions are very important to women in terms of how they manage their lives.

She had a case at the Supreme Court the same year as Roe, and it was a classic Ruthian approach to a problem – which was, Ginsburg represented a captain of the Air Force who became pregnant, and at the time, the rule was that if a woman became pregnant while serving in the military, she either had to have an abortion and she could have one at a military base, usually overseas, or she would be essentially drummed out of the service. And Ruth’s client loved her life in the military. She had made arrangements to have her child adopted, but she wanted to have the child. She did not want to have an abortion. She felt very strongly about that. And under the rules, she was going to lose her military status. So, Ruth took the case to the Supreme Court, they agreed to hear the case, and the government, I think, this was 1972/3, looked at this and said we’re going to lose this case, and politically it’s going to be terrible too because we’re going to have to say that yes, we give women abortions. So, they offered to allow her to stay in the military, and they took steps to change the policy. So, there was no more case. And Ruth always felt, and I do think she was right about this, that if Roe had been decided at the same time as the other case, you would’ve seen the two sides of the coin. On one side were women who wanted to have an abortion so that they could continue their lives in the way they wished, and on the other side was a woman who wanted to bear a child and keep her job so that she could carry out her life in the way that she wished, including her values of not having an abortion.

GL: Did RBG want the Equal Rights Amendment to be passed?

NT: Oh my God, she was wild about it. She really wanted it to be passed, but she also thought that we couldn’t go back and add on states this late in the game, which is what some of the women’s movement want to do. But she thought it was the only way to really be sure that women would not lose some of the things that they had gained.

GL: For me, your epilogue was the saddest part of the book, because you wrote about how the court has changed with regard to respect for norms and etiquette and most importantly trust. You write that RBG noted that the whole notion of the country’s independent jury hinges on public trust. And yet, you say that she always remained hopeful. Do you?

NT: I think that’s the best you can hope for today, is to be hopeful that we can return to some sense of civility and comity in our personal lives, among the people we work with, as well as in our institutions. I think the Supreme Court is the last place I thought we would lose that kind of civility, and we clearly did with that leak. And you can see it to this day; they put on a fairly good show, but their impatience with each other is palpable at times.

GL: And Clarence Thomas has said as much, right?

NT: Yeah, he said he didn’t trust anyone anymore. I think it was at the Eleventh Circuit, he said he didn’t trust anyone on the court anymore and that he loved and trusted, even though he disagreed with, Justice Ginsburg and Justice O’Connor, for instance. He didn’t mention any of the current Justices, and he said that he trusted Chief Justice Rehnquist, but he didn’t mention Chief Justice Roberts, who’s been chief for 17 years now and who he served with during all of that time. And I think that tells you a lot about the state of relations at the court.

GL: At the end of chapter nine, you ask, in our current climate, could a Ruth and a Nina, a Nina and a Nino, or a Nina and a Ted, happen today? Could those friendships ever take root and thrive? And what does the answer to that question mean for all of us? So how would you answer that, and what does it mean for all of us?

NT: I think you have to work at it if you’re going to make it happen. I think that in my case or in our cases, it was fairly natural to happen. It wasn’t all that difficult. But I think you have to be willing to put aside preconceptions about people and see if they have a heart and a mind that you will, this sounds a little bit corny, learn to love, even if you disagree with them very heatedly about some things. I mean, I didn’t just love Ruth. I loved Nino. He was a wonderful human being, and he was always incredibly generous to me, and he was hilariously funny. And I sometimes occasionally took him on, and he could take it up to a point, and then I’d back off.

GL: Is there anything you want to say about this book or your journey that you want people to know?

NT: The one thing I would say about sticking to your own kind, is that you will never expand your brain that way. Never. And somebody who can get you to think differently is important to you as a person, to me as a person… What I think is really important is that we all are very confident sometimes in our own views. And we may be right, but on the other hand, you really do have to have a more varied fabric of thinking than just your little pod.

There’s a story which I actually have no idea if I told in this book or not, but Justice Brennan, I was doing a profile of him, which is how I learned this. So at the time, he must have been in his 50s. It was 1956, something like that. It was after Brown v. the Board, and I think it was in Little Rock. The teachers had refused to go to work if they were going to be in mixed-race schools. And the case is called Cooper v. Aaron, and it went to the Supreme Court and he wrote it. And his neighbor was somebody I knew, and Brennan was sitting on his front porch working, and his neighbor was a reporter who’d been in the South covering civil rights stuff. And he went up and he was standing there just shooting the bull with Brennan, and he said it’s very interesting because schools really hate the word desegregated because it’s pejorative. And Brennan thought about it, and so he changed, throughout his opinion, took it out and he put in the word integrated instead.

And I thought it was just such a small but significant thing that he understood that his audience was not just people who agreed, but people who probably very seriously disagreed.

Nina Totenberg will speak at the Granada Theatre on Tuesday, February 7, at 7:30 pm as part of the UCSB Arts & Lectures Series. Free copies of Dinners with Ruth are available now at the UCSB Arts & Lectures Box Office, and at both the Main Branch Santa Barbara Public Library (40 E. Anapamu St.) and the Goleta Valley Library. (500 N. Fairview Ave.) Visit https://artsandlectures.ucsb.edu for tickets and more information.

You must be logged in to post a comment.