The Mystery of Lobero’s Eagle

by Hercule Beresford

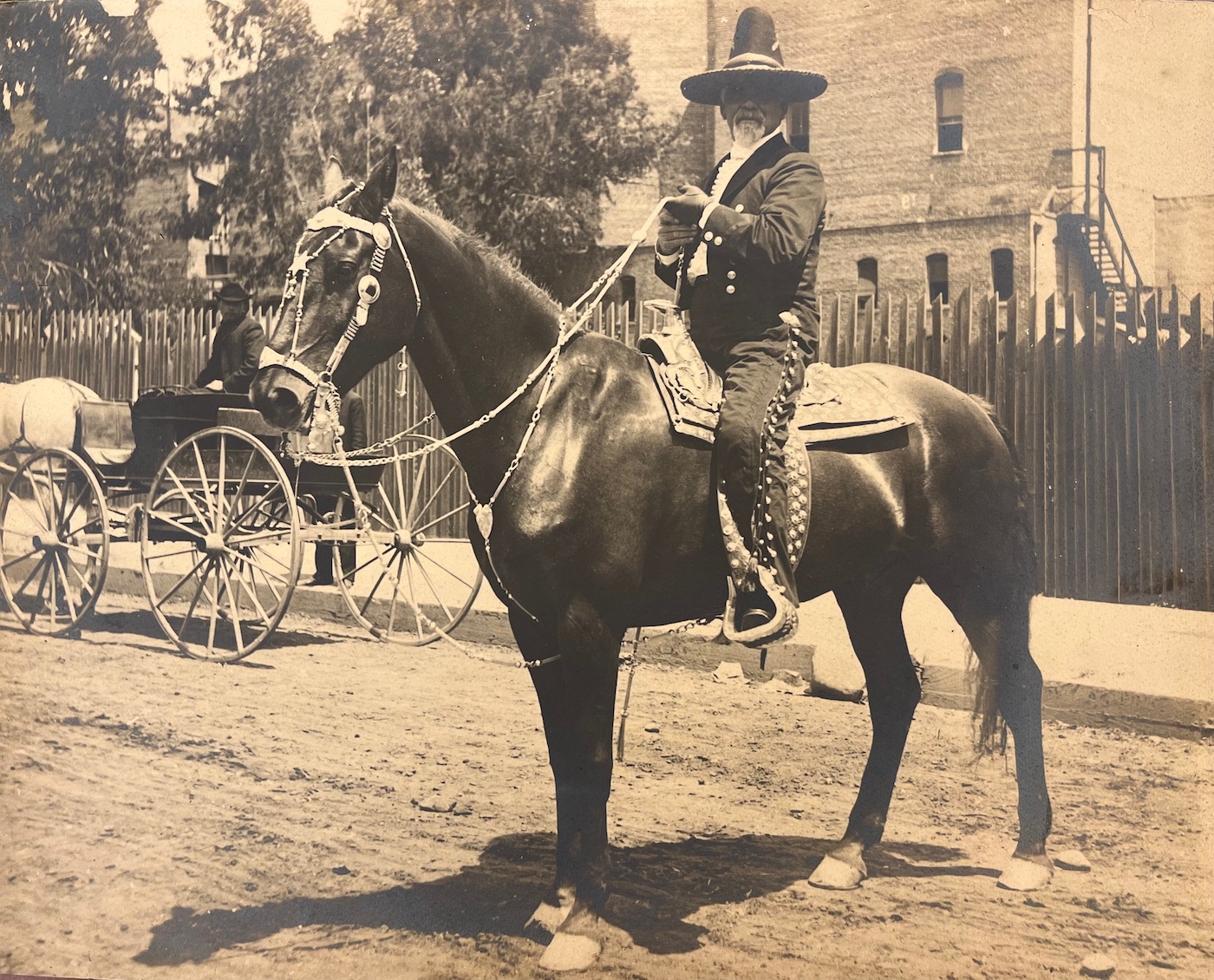

Italian-born Giuseppe (José) Lobero loved his adopted country so much that he opened his opera house, the first theater in Santa Barbara, on February 22, George Washington’s birthday. With such deep patriotic sentiment, it seems likely that it was he who hung a symbol of our nation above the proscenium arch of the new theater.

The large and majestic gilded eagle, representing the strength, boldness, and determination of the American nation, mirrored the immigrant musician and saloonkeeper’s own strength, boldness, and determination in bringing a theater to Santa Barbara. A newspaper article in 1871 commented on his ambitious plans but prophesized that it was unlikely he would get a return on his investment.

Lobero’s resolve must have wavered, however, because in June 1872, when the county considered buying the theater for a new county courthouse, he offered to sell it for $11,000. Nothing came of the plan, and Lobero persevered, training the local population in instrumental music and song for the grand opening on February 22, 1873. The local press, now on board, attempted to build support for the theater by writing, “Let us all turn out and give Signor such a rousing house as will thrill his heart with joy and fill his purse with coin.”

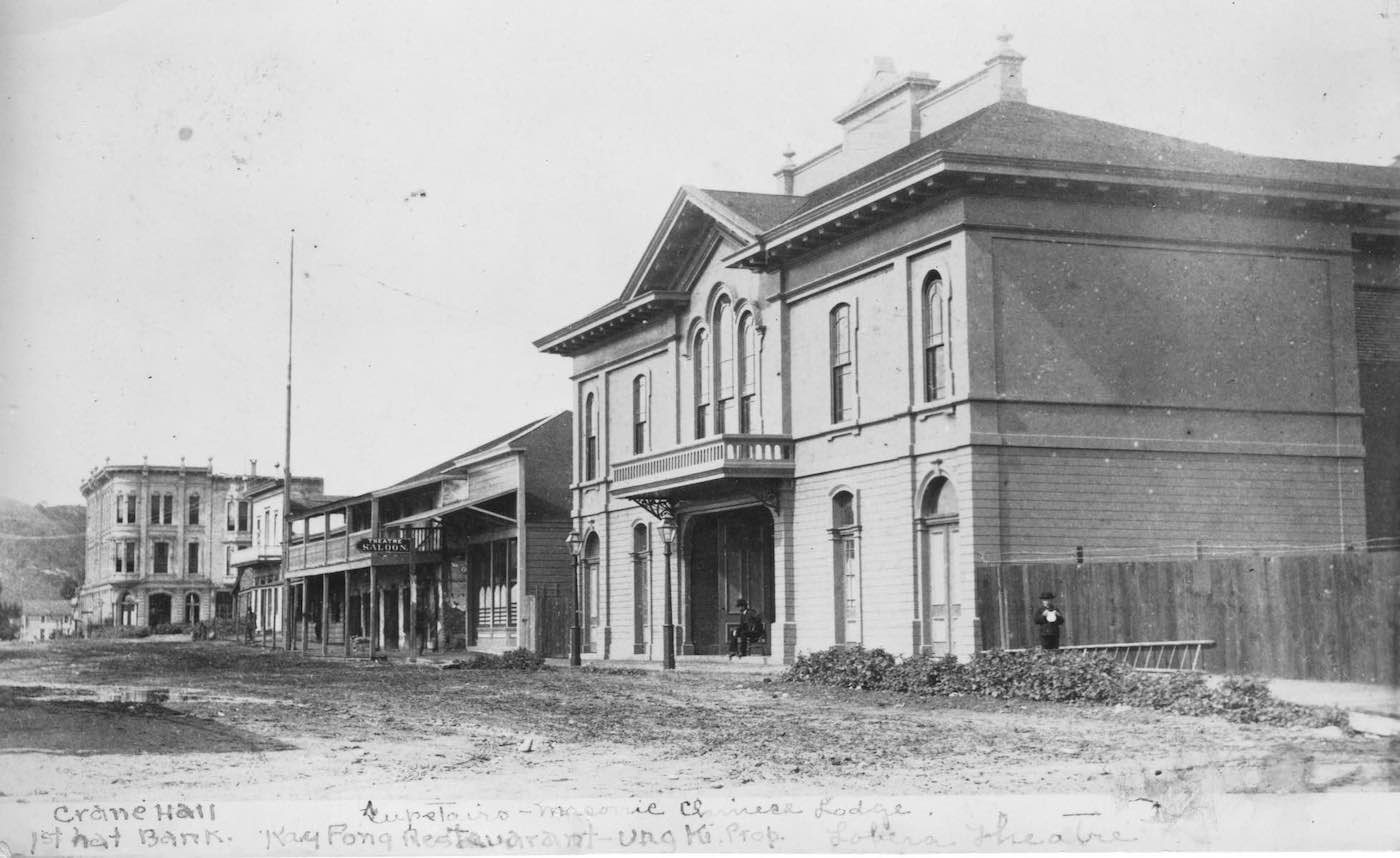

Unfortunately, the original reporter’s financial assessment was correct, and Lobero lost control of his theater after only a few years. Others took over and tried to make a go of it, and it was successful for a long time despite its location in Chinatown, which many considered unsavory, and others found charmingly exotic.

In 1889, there was talk of building a grand new theater with modern improvements, but an opinion in the local paper recommended improving the Lobero instead and said, “Two things about it we should be grieved to see superseded. One is the glorious eagle which hovers over the proscenium arch and the other is the historical curtain…” Eventually, with competition from the 1907 Potter Theater on lower State Street and the advent of movie theaters, the Lobero Theater lost favor. Soon Lobero’s eagle perched in darkness.

In 1921, the Lobero Theatre Company was formed with the goal of restoring the old theater for a community theater. When restoration proved unfeasible, the plan changed, and the old theater was razed so a new modern theater could be constructed. At some point prior to this, the eagle had been released from her lonely aerie above the old proscenium.

When the new Lobero opened in August of 1924, old-timers hoped to once again see the eagle looking down from her lofty perch, but it was not to be. When a frequent visitor to Santa Barbara, Mrs. Marian Parks Partridge, a historian from Pasadena, attended a performance at the new Lobero in 1939, she asked about the missing Haliaeetus. She was told that it hadn’t been seen in 20 years and was probably being used as a decoration in some private home. An appeal was broadcast for its return, to no avail.

At this point, two mysteries presented themselves: From whence had the gilded eagle come and to what new aerie did she go?

Conflicting Provenance

In 1915, a gigantic, gilded eagle with outstretched wings surmounting the shield of the United States was displayed in the window of Ruiz’s Pharmacy on State Street. An article about the exhibit credits Colonel William Welles Hollister with having secured the eagle from the hull of the wrecked ship Fama owned by Captain Alpheus Basil Thompson (a Santa Barbara pioneer who arrived in 1834) and placing it in the Lobero Theatre.

Colonel Hollister had loaned José Lobero the funds to build his theater, and the Hollister Estate owned the theater after Lobero lost it. After its removal from the Lobero, Hollister, according to the article, gave the eagle to Charles A. Thompson, son of Captain A.B. Thompson, who had it newly gilded and painted.

It all sounds reasonable until one takes a second look. In 1846, the year the Fama sank, California still belonged to Mexico. Colonel Hollister didn’t make his appearance in California until 1852, and he didn’t settle in Santa Barbara until 1868. So, what eagle was this?

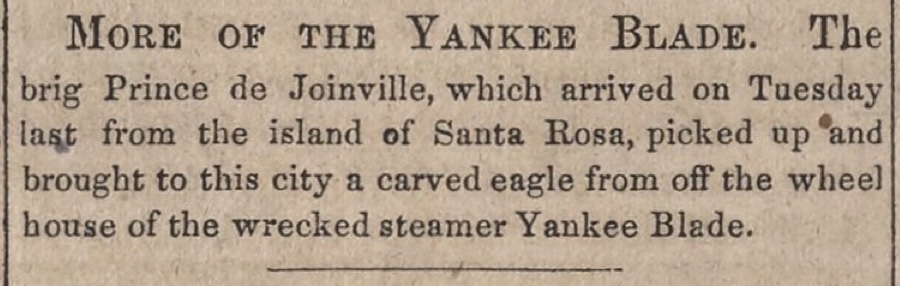

Others say Lobero’s eagle came from the wheelhouse of the steamer Yankee Blade, which was wrecked off Penderales Point near Point Arguello on September 29, 1854. A terrible tale of reckless endangerment, loss of life, depraved thievery of the dead, robbery of the living, and sunken gold kept the story in the newspapers for years to come.

Writing in the 1960s, historian Walker Tompkins said that the Santa Barbara Gazette of Spring 1855 says a wooden eagle off the pilot house of the Yankee Blade was picked up at sea off Santa Rosa Island by a Chinese fisherman, who brought the relic back to Santa Barbara. He traded the eagle to José Lobero for a bottle of whiskey, and Lobero mounted it over the bar of his saloon on the southeast corner of State and Canon Perdido streets where it was a conversation piece for many years before being placed in the Lobero Theatre.

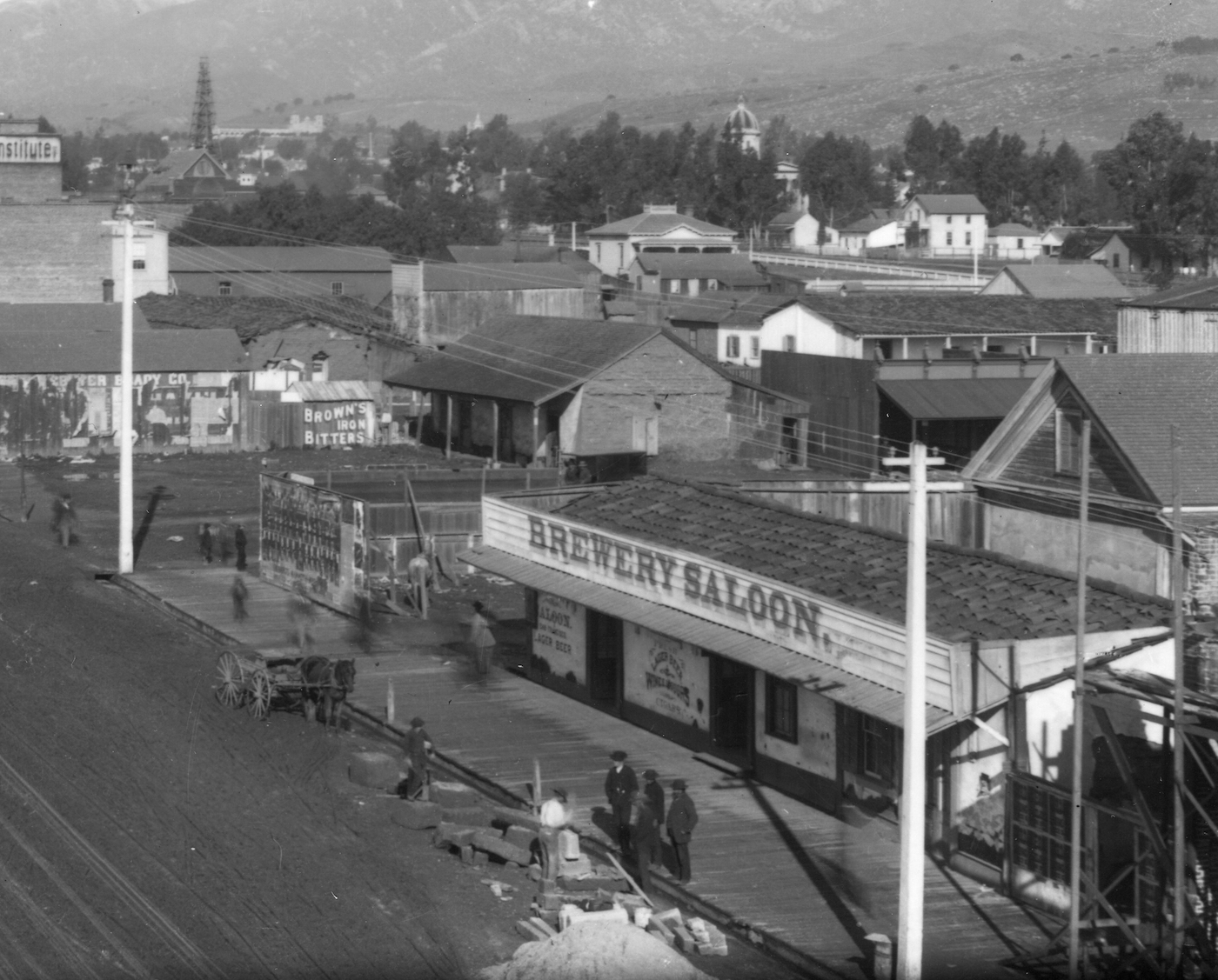

What a fabulous story! Problem is, the evidence doesn’t support it. l searched and read and looked again at the spring editions of the Santa Barbara Gazette (which ran its first edition ever in May of 1855). There is no mention of this Chinese fisherman’s thirst for whiskey nor of his payment to Lobero in eagle feathers. In fact, Lobero did not come to Santa Barbara until 1857 or 1859 (depending on sources) and is first mentioned in the newspapers as the owner of the Brewery Saloon in 1860. With today’s new online archive of the Gazette, my search turned up no Lobero and no saloon and no eagle and no Chinese fisherman.

Ferreting Out the Truth

In August 1855, the Santa Barbara Gazette did report, “More of the Yankee Blade. The brig Prince de Joinville, which arrived on Tuesday last from the island of Santa Rosa, picked up and brought to this city a carved eagle off the wheelhouse of the wrecked steamer, Yankee Blade.”

Years later, in 1881, a judge from Sacramento was visiting at the Arlington Hotel, which was owned by Colonel Hollister and managed by Dixie W. Thompson, nephew to Captain Alpheus B. Thompson. Perusing some books kept on a table in the office, he discovered he knew the man who had written his name inside. The judge asked Thompson about the book, and Thompson said he’d found it and others in a box after the 1854 wreck of the Yankee Blade while he was working for his uncle on Santa Rosa Island. Immediately, efforts were made to return the books to the good doctor who had been a passenger on that ill-fated ship and survived the wreck.

In a letter to Dr. Simmons, Thompson describes his finding the items from the wreck, though he couldn’t remember if he personally took them to his uncle in Santa Barbara or sent them. He wrote, “Dear Sir: … At the time of the wreck of the Yankee Blade I was living on the island of Santa Rosa, in the employ of my uncle. A.B. Thompson. One day while riding on the northwest end of the island, I found a number of pieces of cabin furniture, also cases of lard, and saw many pieces far out in the kelp…. The most valuable woodwork of the Yankee Blade that we picked up was a carved eagle, which came off the paddle-box. This relic is now an ornament in the theater here.”

So, part of the conundrum is solved, but when and who put the eagle in the Lobero is still shrouded in mystery. If she were brought to Santa Barbara in 1855, where was she until the Lobero Theatre opened in 1873? Dixie’s letter, however, implies it was given to his uncle, Alpheus B. Thompson, but after that – who knows.

Escape From the Lobero

While the eagle clearly had flown the coop before the completion of the new theater in 1924, where it landed is still in debate. It’s possible that the eagle placed on display in 1915 came from the Lobero, but the reporter, relying on faulty memory or bad intelligence, had the wrong ship. The Lobero Theatre was certainly mostly defunct by 1915. Then again, a 1920 article on the history of the Lobero Theatre says the eagle was still in residence, though sequestered in the property room. Perhaps she returned periodically to her old abode?

In 1948, local historian Walker Tompkins became fascinated with the mystery of the errant eagle. For the next 12 years, he made her discovery a noble quest. At some point it was given to the Santa Barbara Historical Society which had rooms in the basement of the old courthouse. After the earthquake of 1925, the eagle disappeared again.

In 1960, Ike Bonilla, scion of an old pioneer family and history buff who had joined Tompkins in his lengthy quest, had a strange dream. He visioned an eagle soaring up on San Marcos Pass, which mysteriously turned into a turkey. Upon his awakening, a flash of insight reminded him of an old turkey ranch up on the pass. He decided to check it out and, sure enough, he found a wooden eagle perched on top of the rustic gate at the entrance to the ranch. He then informed Tompkins.

Tompkins raced to the top of the pass to find a wooden eagle covered in barn paint and with an arrowhead piercing her breast, shot, perhaps ironically, with an arrow fletched with eagle feathers.

The property of the turkey ranch had been a stage station belonging to the Kinevan family. Emmett Kinevan told Tompkins that his sister Mary had obtained the eagle in 1929 from Sam Stanwood, who had auctioned off some of the items stored in his Victoria Street Stable after the earthquake destroyed the old courthouse. In 1940, a new owner of the Kinevan property, Leo Olsen, placed the eagle over the gateway to his turkey ranch. Benjamin Franklin would have been pleased. He much preferred the humble turkey for the national emblem and considered the eagle “a bird of bad moral character.”

But was this really the eagle that had flown in the old Lobero Theatre? Bonilla and Tompkins went in search of confirmation. Ike’s uncle Mike, age 86, had been José Lobero’s saloon custodian and played in the orchestra at the old theater. When he was shown a photo of the San Marcos eagle, he confirmed it was the shipwrecked eagle gazing at the audience above Lobero’s proscenium. Other pioneers from Theo Arellanes to Elmer Awl to James J. Hollister, Jr., also

identified her.

After a display at the public library, she was given, or re-given, to the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, where she has perched, stripped of her gilded feathers, permanently wounded but found at last.

The Eagle Today

And then, two years ago, she was adopted by a benefactor by the name of Brett Hodges, an ardent supporter of both the Lobero Theatre and the Santa Barbara Historical Museum. Brett became fascinated by tales of the eagle and has made its preservation and telling of its story of paramount importance. He produced a video chronicling her story, and together with Natalie Hodges and Sharon and David Bradford sponsored her regilding.

This coming First Thursday only, February 2, the public will have an opportunity to view the freshly gilded eagle and the video that tells her story at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum open house. Later in February, the eagle will return to the site of her long-lamented perch in a new aerie in the lobby of the “new” 99-year-old Lobero Theatre. On long-term loan from the Museum, she will overlook the festivities commemorating the 150th anniversary of Santa Barbara’s first theater, José Lobero’s opera house.

Thus concludes the Mystery of the Eagle. Bonsoir.

(Sources: Contemporary articles; articles by Walker Tompkins; article by Ike Bonilla; with many thanks to Brett Hodges for sharing his research.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.