History in a Bottle “Ranchos de Ontiveros” is Nine Generations in the Making

“The wine bottle – it’s the only time machine that works!”

Just one of the many colorful one-liners delivered by wine whiz Wes Hagen, as a small group of wine buffs gathers around the table inside the rustic The Maker’s Son eatery in downtown Los Alamos last month. An authority on all things Santa Barbara County winemaking, Hagen had gathered us for an introduction to his newest grape adventure. After many years at the helm of the now-retired Clos Pepe label in the Sta. Rita Hills, and then representing the myriad wine projects by Santa Barbara’s Miller Family, including labels like J. Wilkes and Bien Nacido, Hagen is now telling the story of Ranchos de Ontiveros – a story nine generations in the making.

Aging wine in bottle over many years is done by design at Ranchos de Ontiveros, which maintains a large inventory of its old vintages, most of which are available for purchase by curious consumers. “We’ve done the cellaring for them!” says Wes. It’s a deliberate effort to track the potential of the sites where the grapes are grown and to trace how the wines change over time.

Several of those bottles have made themselves to our table, and as we sip, the history of Ranchos de Ontiveros unfolds.

The California story of the Ontiveros Family stretches back to 1781, when Josef Ontiveros, a descendant of Spaniards who’d settled in Mexico, journeyed north. Generations of Alta California ranchers and farmers followed, including Juan Pacifico Ontiveros, who, in 1855, would purchase Rancho Tepusquet in the heart of the Santa Maria Valley, a historic land grant, from his father-in-law. The adobe home he and his wife, Doña Martina, built a year later still stands today.

Fast-forward to 1997, when James, a ninth-generation Ontiveros, sets off to study viticulture at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and, simultaneously, plants pinot noir on his family’s historic property, establishing Rancho Ontiveros Vineyard. After a brief stint managing vineyards in Sonoma, and after a seminal trip to Burgundy, James and fellow Cal Poly alum, winemaker Paul Wilkins, launch a wine label to showcase his family’s fruit. They call it Native 9, a viticultural homage to James’ lineage.

James joins us a few sips into our tasting. “I see a lot of noise in the wine business these days – a lot of B.S.,” he says. “The only point of doing this for me is not really motivated by trends and scores. And it’s not pride. It’s seeking high quality in wine that transcends varietal, that has something to say and that impresses with a sense of place.”

And that may be the most significant calling card of Ranchos de Ontiveros: the wines all come from land that were once part of historic land grants. Their soils are unique, and the climate in this part of the Santa Maria Valley favors long growing seasons each vintage, making it uniquely suited to allow wine grapes to reach physiological maturity. “Hang time is everything,” adds Wes.

Today, the Ranchos de Ontiveros wines are made by winemaker phenom Justin Willett, whose own Tyler label consistently garners acclaim. Wes and James use the word “chisel” several times when describing his winemaking approach, which pulls back from the focus on whole cluster fermentation and stem inclusion that defined earlier releases. However, a longstanding focus on terroir, perfume, and “a sense of restraint,” as James put it, remain.

Adds Wes, “In a world of heavy metal wines, we want to be jazz.”

Three varieties make up the Ranchos de Ontiveros brand. Pinot noir is under the Native 9 label. Fruit is sourced from Rancho Ontiveros Vineyard, which is planted on eight acres of grapes, and to as many different clones of pinot noir. We tasted five vintages: the 2020 is savory, gritty, and easy-drinking; the 2018 is nuanced and sexy, with a seductive bit of funk on the nose; I loved the 2017, which is structured and concentrated, but splashy, too; and the 2016 is intense yet bright, with a meaty nose. The highlight for me was the oldest in our group, the 2013 – for a pinot that’s nearly a decade old, it’s super fresh, earthy, and fruit-driven.

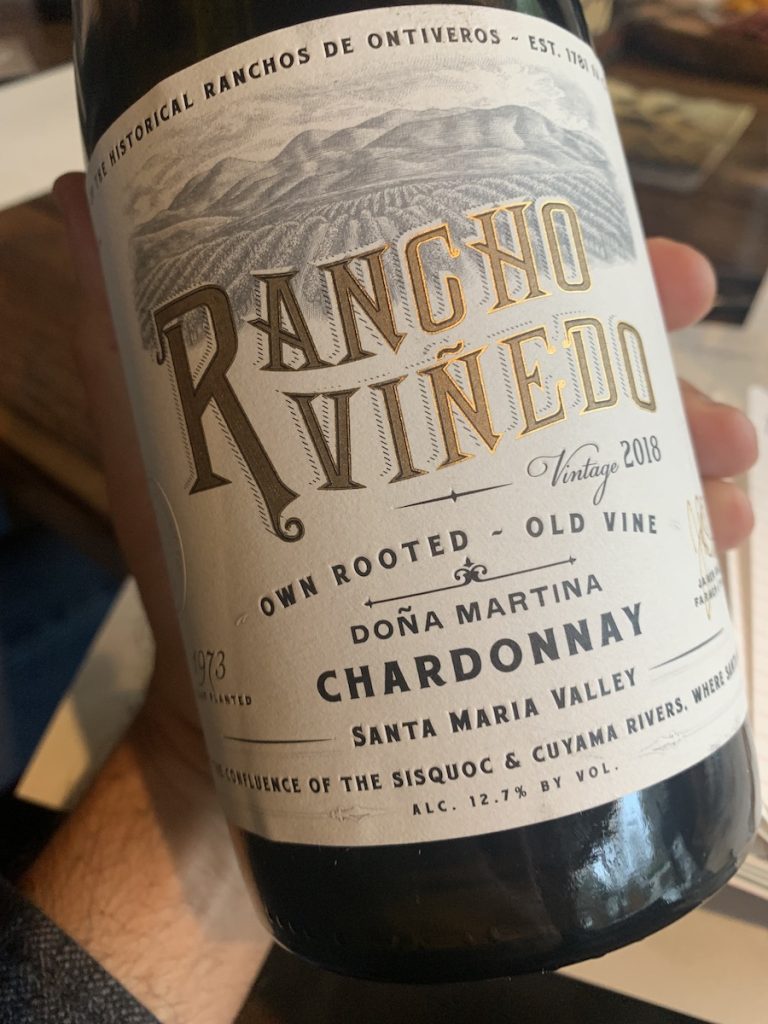

The chardonnays are under the Rancho Viñedo label and, as another ancestral tribute, feature the name “Doña Martina” on the label. Grapes are plucked from a vineyard about two miles north of Rancho Ontiveros, on the other side of the Sisquoc River. James leases this property from the Woods Family and harvests fruit from the same vines that Robert N. Woods planted in 1973.

“Chardonnay is the best grape we grow in Santa Barbara County,” asserts Wes. “It’s a commodity these days, so it gets marginalized. But these wines bust that.” Indeed, the 2019 exudes minerality and freshness, with bright notes and a lovely structure, while the 2018 is a bouncy citrus bomb – zingy and refreshing.

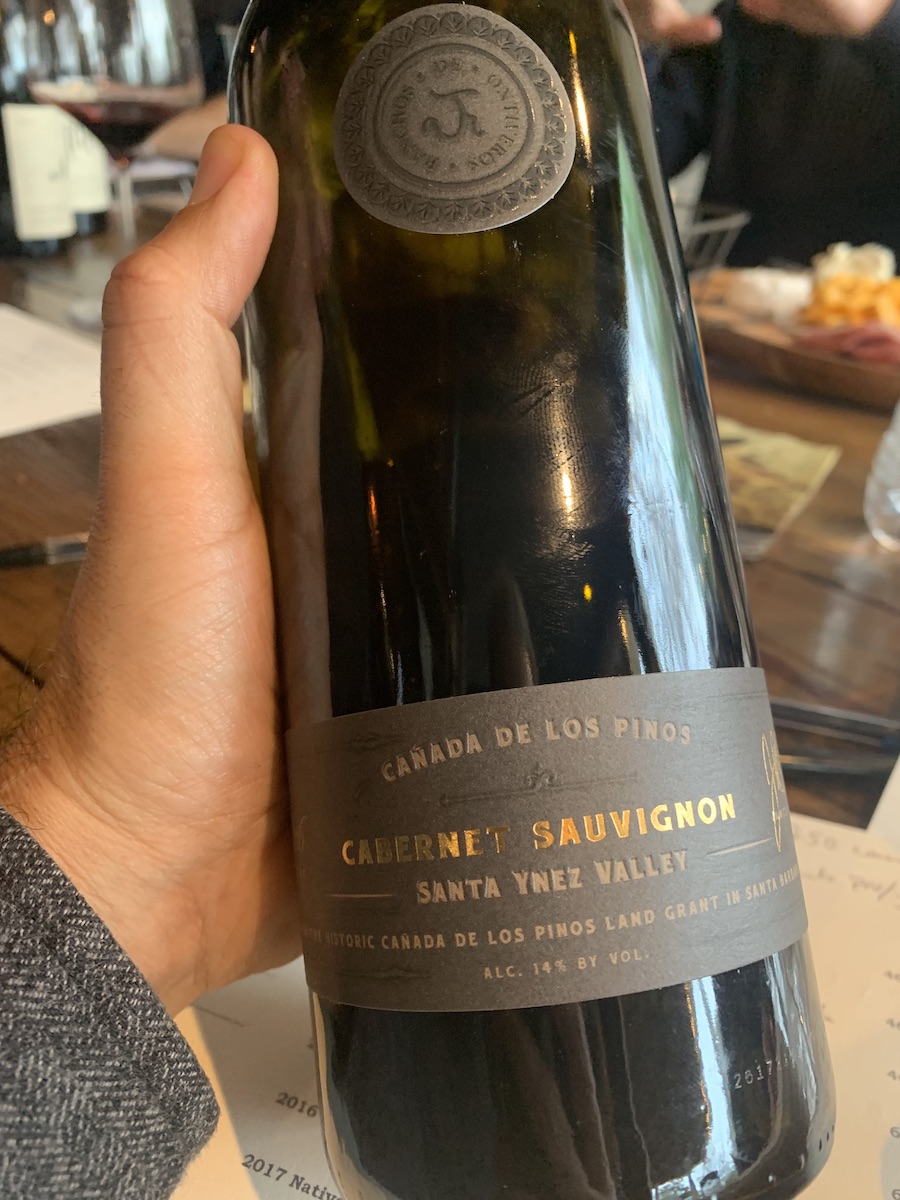

There’s cabernet sauvignon on the menu, too, grown on a vineyard near Happy Canyon in the Santa Ynez Valley that was once part of the Cañada de los Pinos land grant. Aged in mostly new French oak for almost two years, these cabernets are fleshy and chewy. “They’re inspired by the Napa cabs of the 1970s that we grew up on,” says James, and, in a tip-of-the-Stetson to his friends, they’re for “a cowboy palate – big steaks, big wines!” The 2016 vintage we tasted was simply yummy, delivering a complex spice profile and flavors of molasses, chocolate, and cherries.

All the Ranchos de Ontiveros chards retail for $46, and the pinots and cabs sell for $64. The best way to get to know them is to sip alongside Wes, who’s “aiming to give people a curated experience” that includes library tastings and visits to the vineyard. Reach out to him at weswines@gmail.com and find out more at ranchosdeontiveros.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.