Arroyo Hondo Preserve, a Historical Touchstone

Above the riparian corridor of Arroyo Hondo, a bleak Daliesque landscape reveals the aftermath of October’s Alisal Fire. Chaparral that hadn’t burned in too many years fed the wind-driven fire into the canyon from the east. Despite the grazing program of sheep and cattle on the hills flanking both sides of the lower canyon, the inferno advanced, spewing embers into sycamore, live oaks, and manzanita to threaten the historic Ortega adobe and the barn. Aggressive bulldozing by the fire department saved the structures but destroyed 12 years of restoration work.

Rains came, but gently, causing only minimal slides and mudflows, and sparking the rebirth of grasses and yucca. Nevertheless, the danger of a significant debris flow remains, for the upper canyon has been completely denuded, and water and debris must pass through a culvert in the highway. A recipe for potential disaster.

Arroyo Hondo Preserve is one of Santa Barbara’s most significant treasures. The physical presence of historical and natural places in our community provides us with insight as well as spiritual and emotional understanding of our place in time. They foster a sense of belonging to the pageant of all that came before. Arroyo Hondo, whose parade of yesteryears began with the land and indigenous peoples, has progressed to the role of historical touchstone, thanks to meticulous preservation by the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County, which owns and operates the Preserve.

Early Years

Arroyo Hondo’s human story begins with the Chumash, whose presence in various villages and camps along the Gaviota Coast was documented by Spanish explorers beginning in 1512, and whose presence is believed to reach back at least 5,000 years. When Spain began to colonize Alta California in 1769, José Francisco Ortega served as a scout for the Portola Expedition. He later became the first comandante of the Santa Barbara Presidio and grantee of a Spanish land grant named Nuestra Señora del Refugio. The grant gave him permission to graze stock but did not confer ownership of the land, which, according to Spanish law at the time, was being held for the indigenous peoples and belonged to them.

The Ortega family thrived on their enormous rancho partially because it became a center for the illegal trade with foreign nations and, later, to evade taxes and tariffs. The Ortega family was prospering in 1821 when Mexico achieved its independence.

With independence came a program of secularization that seized the vast mission lands and granted them to Mexican citizens. The Ortega family, which had been petitioning to make Nuestra Señora del Refugio a permanent grant for years, received one of the first Mexican Land grants in Santa Barbara County in 1834.

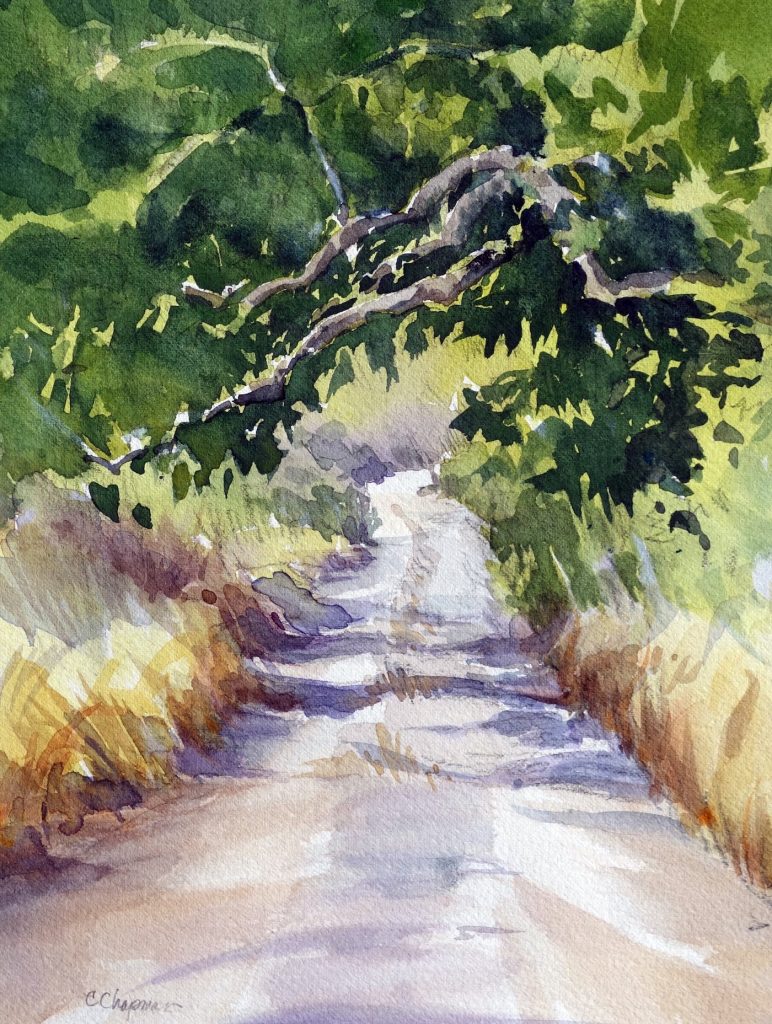

View of the road leading into the canyon after the fire shows the scorched sycamore trees and charred undergrowth. This venerable tree, depicted also in Chapman’s painting, will be evaluated for safety. (Photo by Hattie Beresford)

Chris Chapman’s watercolor of the road leading into the canyon (Courtesy Chris Chapman)

Over the years, Capitan José Francisco Ortega’s children and grandchildren began to occupy the various canyons of the family’s land grant. In 1842, brothers Pedro Regaldo and José Manuel Ortega, his great grandsons, built an adobe in Arroyo Hondo Canyon. Assisting them was Silverio Konoyo, a Chumash fisherman and member of the Brotherhood of the Tomol. Konoyo lived in a traditional brush hut between the Ortegas’ adobe and the beach.

In 1848, California was ceded to the United States after war with Mexico. The peace treaty promised to honor the property deeds of the Californios, but conflicting claims, fraudulent claims, boundary disputes, and “Midnight” land grants by Governor Pico in 1846 caused the courts to get involved. In Santa Barbara County, 42 claims of vast acreage were confirmed. Seven, all but one of relatively small acreage, were either unclaimed or denied. Not the huge land grab most of us have been taught. Nevertheless, the legal costs of getting the grants confirmed caused financial hardships for the landowners, who were “land rich and cash poor.”

The Ortegas of Arroyo Hondo

In addition to the two adobes in the canyon, the Ortegas built a grist mill by the creek and the upper meadow. Here mules turned the wheel that ground corn and wheat grown on the rancho. (The ruins of this mill are protected and were miraculously saved from the Alisal Fire.) As the Ortega clan at Arroyo Hondo grew, a schoolhouse was built in the 1850s. It operated until the mid 1890s, at which time it became a tool shed. Later, chickens came to roost on the abandoned desks.

During the lawless days of Santa Barbara’s early American period, Arroyo Hondo became a favorite hideout for bandits, who used its steep canyon and rough mountains to escape the law. (Today, the “Outlaw Trail” is completely burned over, and banditos would be hard pressed to find a place to hide.) During the 1860s, plagued by drought and taxes, the Ortega family began selling off their land until only two small pieces remained, Tajiguas and Arroyo Hondo.

At Arroyo Hondo, Pedro kept the ranchero custom of hospitality alive. When P.J. Black of Huasna travelled to Santa Barbara during the 1860s, Don Pedro Ortega would offer him a meal and a bed for the night. Pedro also contributed supplies of food for the impoverished Don José, whose annual visit on a fine horse was accompanied by an old pack mule with capacious alforcas.

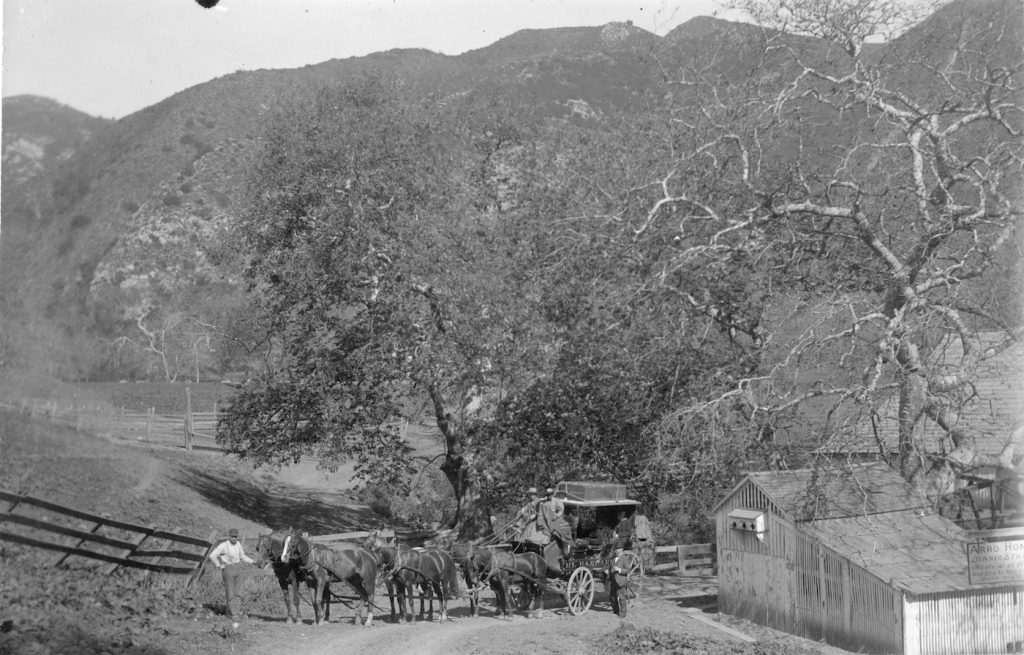

In 1861, the first stage line from San Francisco passed by Arroyo Hondo, and by 1863 the Ortega Adobe was serving as a stage stop and restaurant. As late as 1896, the newspaper was able to say, “The stage ride between Santa Barbara and Los Olivos is very pleasant and travel good. Good eating arrangements at Arroyo Hondo and Lompoc are found.”

In January 1889, Pedro Ortega sold Arroyo Hondo to Estanislaus S. Cordero, though he and other Ortegas remained on the ranch. Pedro died in 1892 and his son Hermógenes came to live in the main adobe to manage the property.

The Gaviota Coast is riddled with canyons draining the mountain waters into the sea. Stage and wagon traffic, and later automobile traffic, had to descend, cross creeks, and ascend the headlands time after time. To construct a rail line along the coast, the Southern Pacific Railroad had to build a series of trestles. During this time over a thousand men worked on the rail line, and Arroyo Hondo became a railroad camp, complete with saloon. When the 541-foot steel trestle at Arroyo Hondo was finished on December 30, 1900, the line was complete.

Hollisters

In 1908, Jennie Hollister Chamberlain Hale purchased the ranch from the Cordero family for a country getaway. Jennie was the daughter of William Wells Hollister, whose name is associated with many ranches throughout Santa Barbara County and beyond. She often took friends and family to the ranch in three touring cars, one of which was loaded with all the proper accoutrements for a fine picnic, complete with food, linen, china, silver, and servants to prepare it all. Of the other two autos, one was for her friends and the other for her dogs.

The same year that the coast route was completed, the first automobile made its appearance in Santa Barbara, and soon a movement for good roads in California led to the construction of the second state highway, Route 2, today’s Highway 101. By 1919, an arched concrete bridge spanned the width of the canyon, and the old automobile road through Arroyo Hondo was defunct. In 1949, the mouth of the canyon was shut off by an enormous earthen berm that carried the highway. It was equipped with a large culvert, and legend has it that Jack (John James Hollister, Jr.) demanded it be large enough for him to herd his cattle to other pasturages along the coast, all the while riding his horse and wearing his Stetson.

Barbara and J.J. Hollister at the 2009 Arroyo Hondo en Plein Air fundraiser, initiated by Chris Chapman and John Iwerks. Invited artists donated 50% of sales to support the work of the Arroyo Hondo Preserve. (Photo by Hattie Beresford)

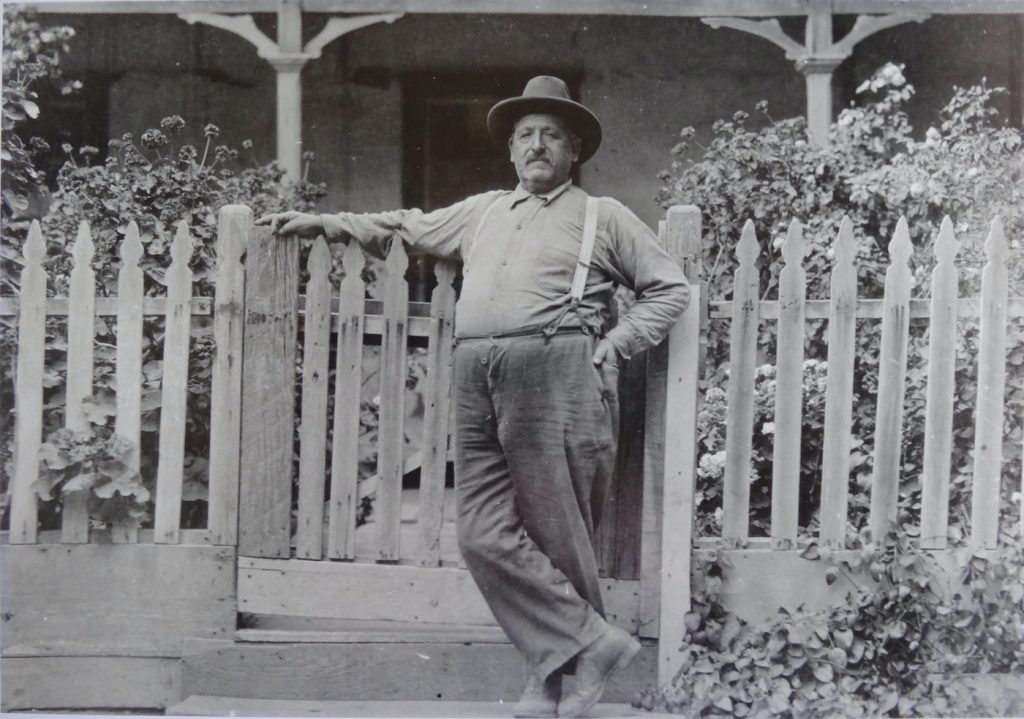

Vicente Ortega, seen here in the meadow in 1969, was the last Ortega to live on the rancho, which he managed for the Hollister family. When he died, his ashes were scattered in the meadow, thereby returning him to the home he had loved so much. (Courtesy Chris Chapman)

Through a variety of Hollister and Chamberlain owners, Ortegas continued to live at Arroyo Hondo. The last Ortega, Pedro’s nephew Vicente, continued living there until 1978.

Jack’s son, J.J. Hollister III, and his wife, Barbara, moved into the adobe in 1991, at which point a marvelous thing happened — J.J. persuaded the other owners of the ranch to sell to the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County in 2001. By doing so, they preserved a living touchstone to our history, a legacy beyond price, a gift to future generations.

Under the auspices of the Land Trust of Santa Barbara County, Arroyo Hondo became a nature and history preserve that is open to the public, at no cost. They brought back the steelhead trout that had long disappeared due to the earthen highway berm. They worked to restore native habitat, created educational programs, hosted school children for nature walks, recruited a talented and dedicated group of volunteers and docents, and they built trails and picnic areas for all to enjoy. They filled the Ortega Adobe with works of art and historic documents and items. And then in March 2020, after the United States finally woke to the seriousness of COVID-19, Arroyo Hondo closed.

COVID and the Canyon and the Fire

As a frightened nation learned more about the disease, and protocols were put in place, Arroyo Hondo made the decision to provide a safe respite from “cabin fever” and social isolation. It reopened with clear COVID guidelines in place. Formerly reserved for docent-led school groups, Mondays and Wednesdays were now open to the public. Though reservations were required, they were free, and, best of all, the more than 800 acres of preserve were open to a maximum of 30 people at a time. Talk about safe “social distancing.” Even then, people were required to wear masks if they were with non-household members. People came from all over the state to find relief in nature at Arroyo Hondo. (It was glorious, and my husband and I took full advantage of the opportunity, signing up several times and always giving a much-needed donation.)

As COVID-19 restrictions eased with the advent of vaccines and lower case numbers, the Land Trust proceeded to plan for the Preserve’s 20th birthday. School groups were invited back. It not being possible to have docent-led tours, the docents created a family self-guided tour. Things were looking up until the canyon burned in October.

The self-guided signposts are ash now, as are many of the sites described. Work is underway to create a new tour, one which includes the role of fire in the Arroyo Hondo Preserve and which tracks and celebrates the rebirth and resilience of the natural world. Sally Isaacson, Arroyo Hondo Education and Volunteer Coordinator, is hoping a host of white mariposa lilies will play counterpoint to the charred earth, and she eagerly awaits surprises as native plants regenerate.

John Warner, Arroyo Hondo Preserve manager, sees an opportunity to learn more about the canyon’s response to fire. He hopes to bring in fire ecologists to implement a study using time lapse cameras to record regrowth in habitats and soil types. It is John, along with many volunteers, who works tirelessly to maintain and restore the beloved canyon.

Everyone’s main concern, however, has been for the animals. Melted night vision cameras have been replaced and are being monitored to detect the comings and goings of the denizens of Arroyo Hondo. So far deer, a bear, a ring tail, and tree squirrels have been spotted. Birds of prey seem to have weathered the fire storm, and hawks and peregrine falcons can be found perched in trees near the creek and soaring on the updrafts. In the creek, turtles have poked their heads out of the ash dusted pools.

Much work needs to be done. The Land Trust has hired a tree company to evaluate the safety of trees along the trails and several have been slated to be removed or cut back to a safe level. Damaged trees will be carefully observed for signs of regrowth. Trails need to be rebuilt, repairs must be made to water systems, equipment must be purchased to do the work, and money must be raised to make it all happen.

Historic Fires in the Canyon

This is not the first time the canyon has burned. On September 17, 1889, a fire that broke out in the coastal range was described by a traveler headed for Los Olivos over Refugio Pass. “The drive over the mountain was grand,” he wrote. “On all sides of us were mountain fires that looked like immense volcanoes sending forth streams of flames.”

By September 24, Miquel Burke of Gaviota, who had been fighting the fire and was less enthralled with its awful beauty, reported that all the rangeland on the coast side of the mountain was scorched and miles of fences had turned to ash. The fire had spread so fast that horses, sheep, and cattle were unable to escape.

In September 1955, a fire broke out near the summit of Refugio Pass. Within hours it had consumed the desiccated ceanothus and manzanita and spread to both sides of the mountain between Gaviota and Goleta. The now all too familiar conditions of heavy, dry brush, heat and wind, and steep, inaccessible terrain kept the mountains aflame for 10 days. Sage exploded as temperatures approaching 1000 degrees generated their own winds and currents. Arroyo Hondo burned along with its neighboring canyons and ranches. Somehow, the main adobe survived, but the original barn was destroyed.

Arroyo Hondo recovered from the 1889 fire, and it recovered from the 1955 fire. It will recover from this one. Meredith Hendricks, executive director of the Land Trust says, “With a little time, some gentle rains, and thoughtful stewardship, Arroyo Hondo will come back to life.”

May soft rains bring on a miracle of rebirth, and the preserve add another purpose to its mission, that of educating the public about fire.

Since 1985 the Land Trust has helped conserve nearly 30,000 acres of farm and ranch land, wildlife habitat, and natural areas and places. To contact the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County to get more information on its projects or donate for “Giving Tuesday” go to www.sblandtrust.org. •MJ

Sources: Chris Chapman, who, together with her artist husband John Iwerks, was a preserve manager at Arroyo Hondo for many years, wrote a beautifully illustrated and well-researched history of the canyon rancho entitled Stories of Arroyo Hondo. Much of the history for this story comes from her book. Other sources include Santa Barbara Independent, “Refugio Fire September 6-15, 1955” by Ray Ford, 19 September 2009; Santa Maria Times, 20 February 1892; and interviews with John Warner, Sally Isaacson, and Katie Szabo — thanks for the tour!)

You must be logged in to post a comment.