Marcus Samuelsson’s The Rise Takes Foodies on a Black American Food Adventure

A few months ago, my bestie, Lynn, a librarian and bibliophile, gave me a vintage copy of How to Talk with Practically Anybody About Practically Anything (Doubleday & Co., 1970), a guidebook to the art of conversation, written by none other than the godmother of celebrity interviews, Barbara Walters. Among her subjects: tycoons, royalty, politicians, clergymen, and military.

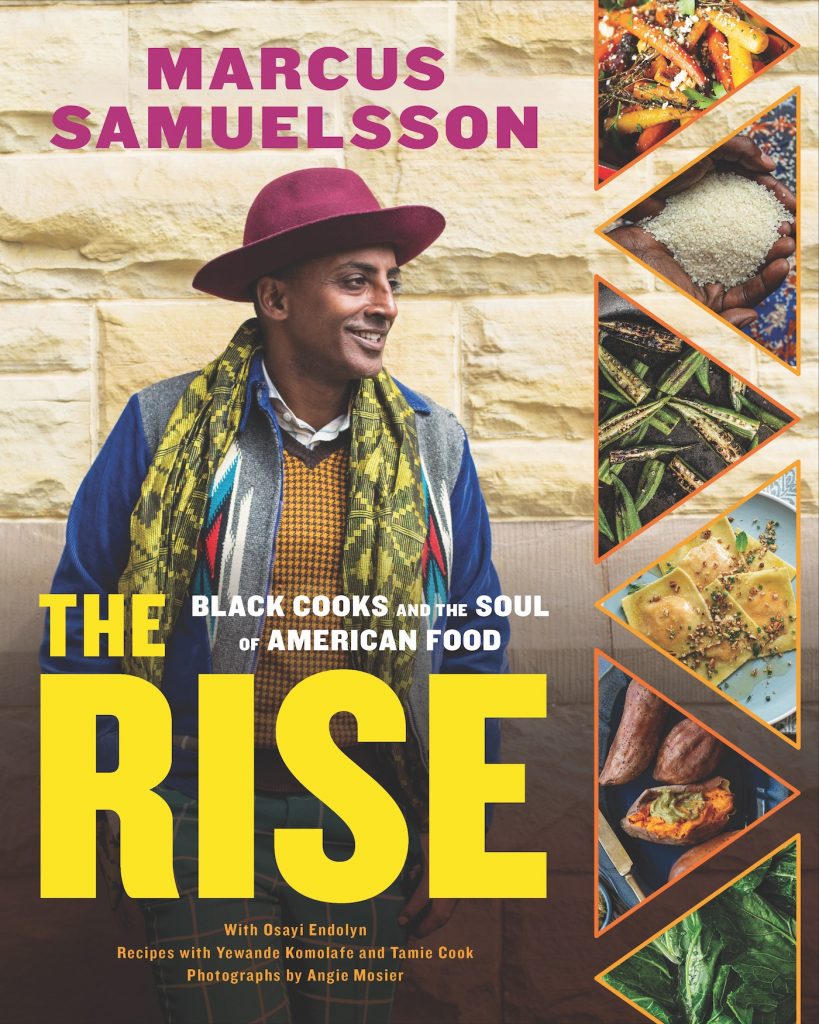

Notably missing was a section on how to speak with famous chefs, althoughthe first chapter, “How to Talk with the Celebrity (Who May Be Nervous Too),” was a great opener. I kept this chapter in mind when I recently reached out to James Beard award-winning Ethiopian/Swedish chef and author Marcus Samuelsson, whose cookbook, The Rise: Black Cooks and the Soul of American Food (Little, Brown, 2020), celebrates the history of Black American food and a new generation of cooks.

The Harlem chef and restaurateur shares his own astonishing journey alongside the stories and dishes from Black chefs and writers across the country. (A few weeks ago, Samuelsson and Santa Barbara’s Petit Valentien chef and co-owner Serkaddis Alemu were featured on Food52’s Counter Jam with Peter Kim to discuss the art of making injera.) The book’s deeply rooted and delicious plates include baked sweet potatoes with garlic-fermented shrimp butter; pork griot with roasted pineapple and pikliz; Haitian black rice and mushrooms; tomato and peach salad with okra, radishes, and benne seed dressing; crab curry with yams and mustard greens; coconut fried chicken with sweet hot sauce and platanos; oxtail pepper pot with dumplings; and citrus cured shrimp with injera handrolls and awaze, a spicy sauce.

Samuelsson’s acclaimed Red Rooster eatery is a hub for culinary innovation, a place that celebrates Harlem’s past and (gentrified) present with cooking classes, music, and local art. This summer, Samuelsson is busy with a new restaurant, Marcus at Baha Mar Fish + Chop House in the Bahamas, as well as a collaboration with Bombay Sapphire that includes a series of virtual culinary classes by the chef and three other renowned Black chefs, culminating into an outdoor art exhibit by Harlem-based graffiti and contemporary artists. The Montecito Journal recently caught up with Samuelsson to discuss his culinary influences and the inspiration behind The Rise.

Q: You were born in Ethiopia and raised in Sweden. How did you learn to cook Ethiopian cuisine and how important was it in the process of identifying with your cultural heritage?

A. I deeply admire Ethiopian culture, food, and spices and am continually inspired by it. Since I grew up in Sweden, I didn’t start cooking Ethiopian food until I was already a professional chef. I learned during my travels in Ethiopia and of course through cooking with my wife and extended family. My wife can definitely show me up when cooking Ethiopian food in our household.

What are some examples of how you have combined Scandinavian culinary influences with Ethiopian cuisine or vice versa?

Since I was about six, I was always in the kitchen with my grandmother, Helga, or out fishing with my father and uncles. This is where I learned so much about seasonal food and fresh ingredients. I pull from certain Swedish staples such as pickled vegetables and an emphasis on seafood. Whereas I use a lot of Berbere, an Ethiopian spice, as well as several different Ethiopian grains in my cooking. Both remind me of home and are a guide for how I create in the kitchen.

Your book explores the artistry and ingenuity of black chefs, and how centuries-old recipes have evolved into new and exciting cuisine with a variety of cultural influences. Can you elaborate a little bit about this evolution?

A lot of the journey of this book, and in my own cooking, is to rectify and honor Black stories. So many of our foods were taken from us or renamed when removed from the African continent. These ingredients seem common today but hold such a deep history and are a key to sharing the stories of Black cooking. Chefs are always evolving traditional culinary dishes which is one of the most creatively satisfying aspects of being a chef. In my own cooking, I love fusing both old and new culinary traditions.

How did you select the chefs featured in The Rise?

As soon as we started talking about this project, Osayi Endolyn and I focused on how to create an accurate, expansive portrait of Black cuisine in America today. I knew there was a great disconnect between the rich history of Black cuisine in America and the public’s larger understanding about Black food. It’s not monolithic, so we wanted to include recipes and people who could show that. From restaurateurs to chefs to historians and authors, every member of the Black culinary tradition made this book possible. We wanted to confirm that this isn’t happening in one city or coast, but that Black food is entrenched in American identity and continuing to evolve.

The Rise was published around the same time as the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. Why is The Rise particularly relevant now and how does social change intersect with your work as a chef?

Racism has unfortunately been plaguing our country since its very founding and it’s such a prevalent and ongoing issue. I’d say that social change has always intersected with my work as a chef in one way or the other. I recently created Black Businesses Matter Matching Fund with [online platform] Sage Plus as a way to build back the small, Black-owned businesses that were disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Black food stems from the domestic, and because of that it hasn’t changed for a long time. Black people, and specifically Black women, have laid down the foundation for success for every single Black person that came after them. Often these changes were linked to food and home and that sense of belonging. I think the work done in The Rise is particularly relevant now because these conversations are so important to discuss, and food can make difficult topics easier to digest.

At the onset of coronavirus, Red Rooster in Harlem was transformed into a community kitchen in which your staff became frontline workers, serving chicken, gumbo, and chili con carne to up to 500 people a day. What inspired you to take on this enormous undertaking and how did it align with your vision of community and multiculturalism?

There was never a question to me that Red Rooster would continue to do what it has always done best: feed the community. Along with my friend, Chef José Andrés, and World Central Kitchen, we were able to immediately start feeding those in need within Harlem, Newark, and Overtown in Miami. In the 230,000 meals we served during the pandemic, our regulars were at times people experiencing homelessness, former inmates, teachers, or construction workers. I was inspired to do this work because I felt obligated to give back to the communities that have given me so much over the years.

How does The Rise seek to break cultural barriers with food? What would you like readers to take away from it?

When food can be made in the comfort of one’s home, you welcome the flavors and traditions of a different culture into your dining room. By creating a cookbook with recipes of Black food that can be made in home kitchens, one can become familiar with the wonderful flavors that make up what Black cuisine is. I hope readers can gain a better understanding of Black food in the United States, the history and importance of this food, and then use their newfound knowledge to have delicious meals and insightful conversations with others.

You must be logged in to post a comment.