A Brief History of the Development of Montecito

Erroneously translated as “little mountain,” the name El Montecito is an archaic use of the Spanish word meaning woodland or countryside. It was being used to designate the eastern part of the Pueblo Lands of Santa Barbara as early as the 1780s. Considered a wilderness, it only became populated when retiring soldiers of the Presidio, in lieu of pensions, were given land in this hinterland far from the center of town. By then, the small Indian village by the sea, called Salaguas by the native Chumash and Rancheria de San Bernardino by the Spanish, had ceased to exist.

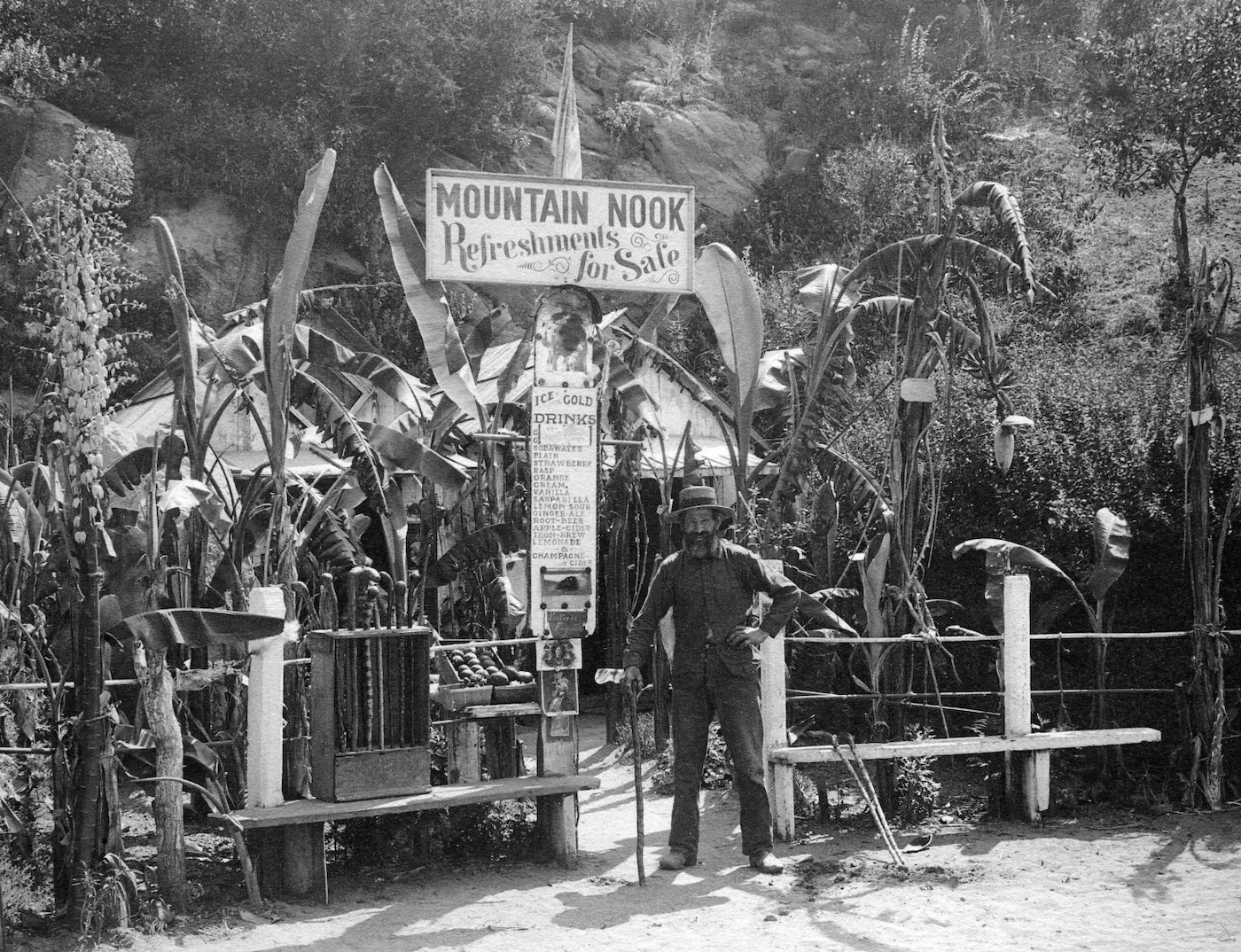

As the Spanish population increased, clusters of dwellings grew, and a small aldea became established along today’s East Valley Road near Montecito Creek. Complete with rooming houses, an inn, grocery stores, dance halls, and saloons, the village served the needs of residents.

Spain yielded to Mexico in 1821, and Mexico yielded to the United States in 1848. A trickle of American farmers looking for inexpensive arable land joined a trickle of land speculators to take up grants offered by the Common Council of Santa Barbara for a few dollars an acre. Many of the Spanish families living in El Montecito added to their holdings at this time.

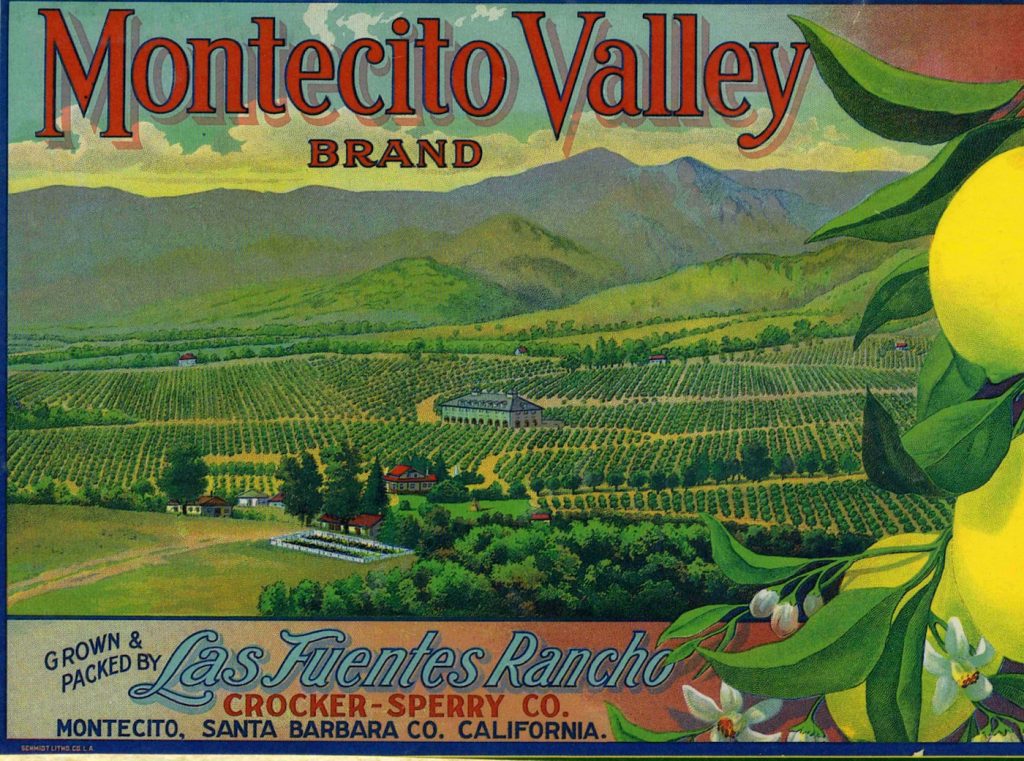

Probably the first American farmer in Montecito was Newton M. Coates. His farm would later become a ranch named Las Fuentes (the springs) owned by William H. Crocker. William was the son of Charles Crocker, one member of the partnership known as the Big Four, the group that built the western end of the first transcontinental railroad. William’s partner was his mother-in-law, Caroline Sperry, matriarch of a flour empire in Stockton. Crocker planned to develop the ranch as 33 ranchette home sites, but when the real estate boom of 1885-86 went spectacularly bust in 1887, he shifted gears and established a citrus ranch. It would be more than 80 years before the property became a gated residential community and golf club named Birnamwood.

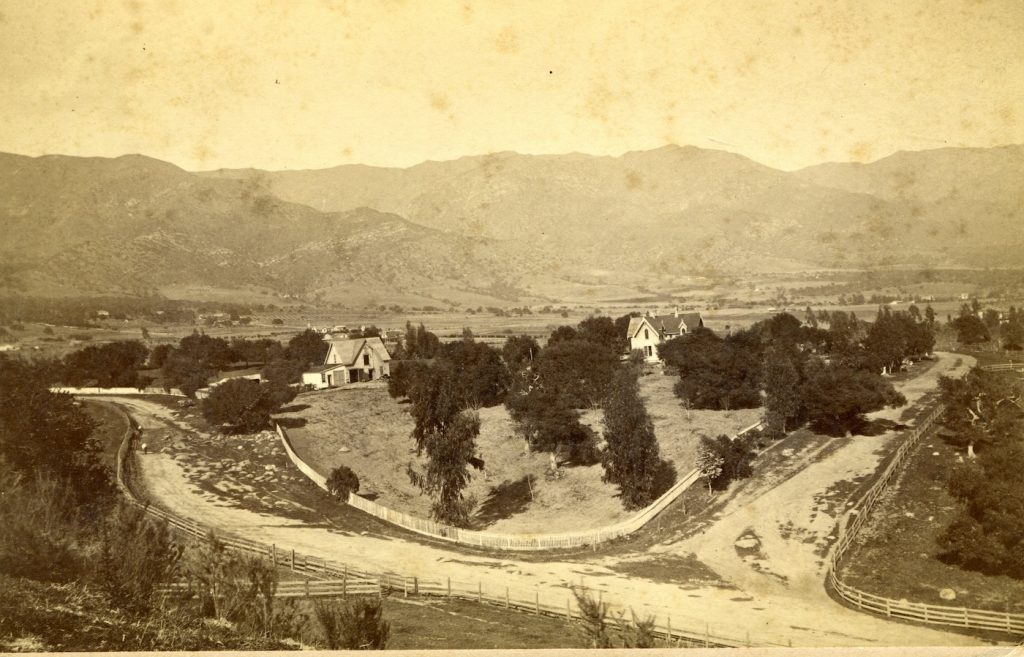

By 1890, Montecito had been discovered by well-to-do Easterners who built elegant Victorian-style homes and estates, mainly as winter residences. The old Spanish families and American farmers found themselves sharing the land with an increasing number of these part-time residents. Over the years, however, many of them would eventually make El Montecito their permanent address.

Land speculation and subdivision increased, and by 1920, a second wave of newcomers had succumbed to the charms of the area. They favored a new style of architecture, Mediterranean and Spanish Revival, which came to dominate the architectural landscape. The old adobe homes of the Spanish settlers and the Victorians and wooden farmhouses of the previous wave of Americans began to disappear.

Increased population led to increased infrastructure needs. Prone to drought, fire, and flood, Montecito has a history of struggling to find a reliable water supply. Early on wells were dug, creeks tapped, and water adits drilled, until finally a tunnel through the mountain brought water from a dam on the Santa Ynez River in the 1930s. The water problem, they believed at the time, was solved. The Montecito Water District, which built the system, had organized in 1920 to unify and serve the water needs of the area. Solving the water problem encouraged new growth; new growth required additional water, and the water problem arose again.

A Case Study: Mira Vista

The story of Mira Vista exemplifies the development of Montecito. In 1891, between Sycamore Canyon and Ashley roads lay a large parcel of farmland with a two-story farmhouse. Though the soil was rich, the market for farm products was slim, and the farmer had sold out to a land speculator, Frank M. Gallaher. That year, 20-year-old Isaac G. Waterman, sole heir of his wealthy Philadelphia family’s estate, purchased the property for $75,000.

A frail and sensitive lad, he had been brought to the reputed health resort of Santa Barbara in the mid-1880s by his grandmother. At that time, he threw himself into the musical life of the community, taking flute and piano lessons from Professor W.J. McCoy and playing the concerts given by the Amateur Musical Club. There he met his future wife, Jean Alexander, who was 10 years his senior. His friends had misgivings about the liaison, in fact, upon hearing the news Mrs. Robert Bage (Marie) Canfield was heard to utter, “Mon Dieu, c’est une catastrophe!”

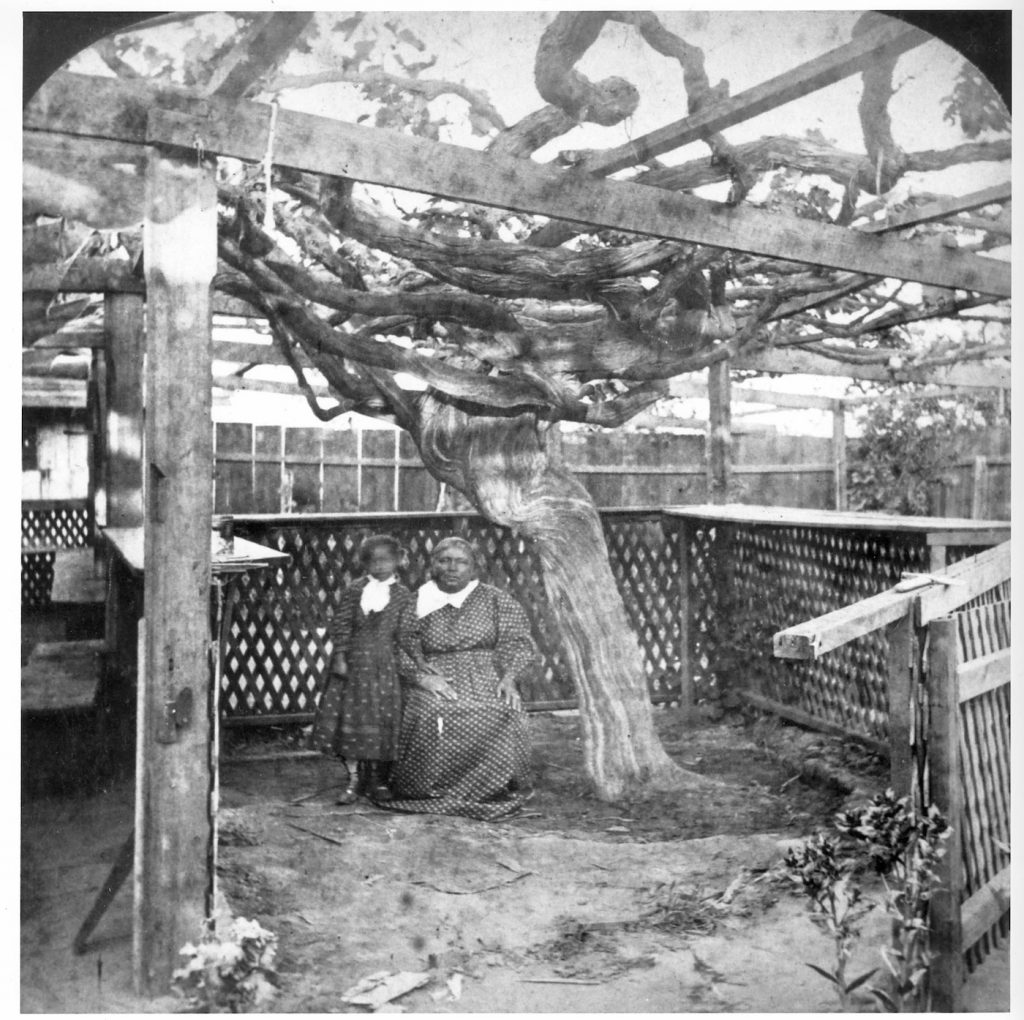

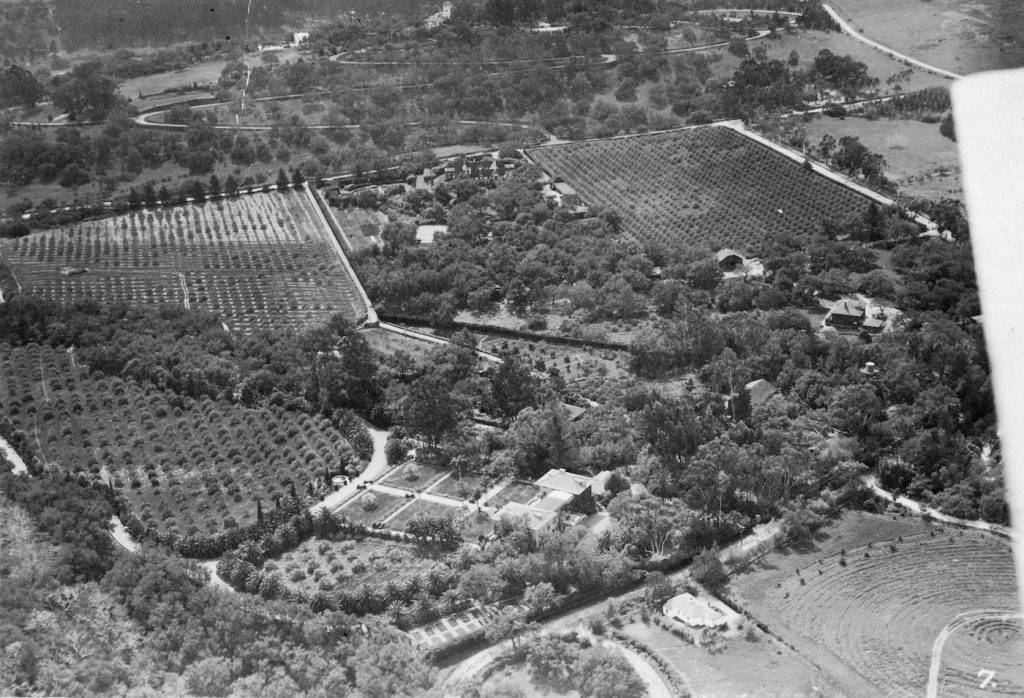

In 1894, the Watermans added a two-story sandstone addition to the house described in the newspaper as “a large and picturesque stone castle in the old Spanish style with a court and fountain in the center.” The interior woodwork was made from redwood and every room had an open fireplace. Electricity lit the rooms and a gas plant was placed on the property. Eventually, a blacksmith’s shop and stable built of stone were added. The lemon orchards produced 800 to 1,000 boxes of lemons a month. The formal terraces and landscaping, designed by Elizabeth Eaton Burton, cost $25,000 and Waterman spent over $200,000 improving the place over the years.

In 1896, the Watermans summered in Philadelphia, and in 1897 Mme. Canfield’s prediction of catastrophe came to pass. Jean took her two girls, moved into her parents’ home in Santa Barbara, and filed for divorce. Waterman became increasingly solitary, reneged on his debts, and rented the house out for several seasons until he finally sold it. Nevertheless, it was at Mira Vista that Theodore Roosevelt and cortège stopped to take in the famous view of the channel, the islands, and the mountains during his 1903 visit to Santa Barbara. Unfortunately, the views were deeply enshrouded by “May Gray,” and the party quickly moved on.

In 1905, Howard Ashton Richardson of New York and Montreal paid $85,000 and owned the home for two years. For the short time they were here, the Richardsons threw themselves into Santa Barbara society. The most famous party the Richardsons gave was a barbeque for the admiral and officers of the Pacific Fleet who visited in December 1906.

Long before Santa Maria barbecue became legendary, Richardson arranged for Spanish costumed waiters to roast two whole beeves and a bull’s head over an open fire in his eucalyptus grove. Long tables, set up on the terraces under sheltering oaks, sported pots of red and yellow chrysanthemums, and red and yellow ribbons festooned the chairs. After the exhibition of bronco busting and a bullfight, a troupe of dancers and musicians from Mexico provided entertainment. In 1907, the Richardsons sold Mira Vista to Alexander Russell, who leased it out when not occupying it.

After renting the property for two seasons, William G. Henshaw, an entrepreneur from Piedmont, California, and his wife, Mehitabel (Hetty), purchased the estate in 1913 for $130,000. The Henshaws completed major renovations, adding a story to the west wing of the house and changing the entry door and long arch, creating three arches instead. They replaced the old wood frame portion of the house with a three-story stone structure that matched the new west wing. They also added a red tile roof and a gatehouse.

The house now had 15 bedrooms and 10 baths. A separate garage could hold 12 automobiles. They added a lake fed by a natural spring and placed a small island in it. The Henshaws became a vital part of Santa Barbara society and their estate was used as a set for the unreleased 1940s film, Brazil.

In 1945, the Devereux Foundation, a boarding facility and school for children with developmental disabilities, bought the property for $50,000 and planned to use it for its younger students. Deciding to use the Campbell Ranch property that they had purchased in Goleta instead, they sold Mira Vista to Westmont College for $85,000 in 1946.

Westmont called it Emerson Hall and used it as a girls’ dormitory until 1969 when it served as a men’s residence hall for one year. Westmont enclosed the rooftop loggia and turned the space into dorm rooms. They later sold it to a woman who turned it into a boarding house. The property became rundown and dilapidated, the once grand landscaping replaced by junked cars and refuse. So many complaints were filed that the Montecito Protective Association got into the act, trying to find a solution to “the hippy problem” at 760 Ashley Road.

Eventually, the upper portion of the old Mira Vista estate was parceled into four lots. A plan to divide the lower bulk of the estate into 30 parcels in 1978 came to naught, but Mr. and Mrs. Masin, who had purchased the entire lower acreage, built a Spanish hacienda-style home and were able to split the property into six lots.

In 1993-94, the Gale family purchased the old Mira Vista estate house. Unlike so many new owners of antique estates gone to seed, Mrs. Gale decided to preserve the aged dowager and return her to former glory rather than bring in the undertakers. She removed the unsightly dorm rooms, brought back the rooftop loggia, and completely and meticulously restored the grand old house and its terraces to their former charm and beauty, thereby preserving an incredible piece of Montecito history.

(Sources: Myrick, David. Montecito and Santa Barbara; files of the Montecito Association History Committee, the late Maria Herold, and my previous research from too many sources to list)

You must be logged in to post a comment.