Santa Barbara Finally Getting Some Traction with Its Homeless Population

Amid a 120-day cleanup of homeless encampments, the question becomes: What happens on Day 121?

You might not have noticed Joe — or maybe you did but kept your eyes on the road in front of you.

Joe, a senior citizen, would panhandle at numerous off-ramps around Santa Barbara, spending 16 years sleeping on the streets, looking for aid while managing severe pain.

Official help? He had a hard time trusting it. Hope? “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.”

Yet, City Net didn’t relent.

A City Net case manager visited with Joe 14 times on the streets, all in an attempt to overcome his distrust of service providers, as well as police presence.

The organization prides itself on street-level outreach, going to where the help is needed, not expecting that people will come to them.

It was finally Joe’s turn to relent.

The consistency of visits managed to establish some semblance of trust, allowing him to be outfitted with the necessary paperwork and receive the medical attention he needed in order to get on a path to be rehoused — with Joe’s case manager submitting the needed info for Joe to access housing resources through Santa Barbara County’s Continuum of Care.

In total, it took 13 months to land Joe in a senior living facility, with bridge housing offered in the interim. It took 14 agencies to collaborate on Joe’s journey to permanent housing — an effort that included more than 168 interactions with Joe.

The result? An 83.3% decrease in his need for emergency room visits, as well as a 99.8% dip in number of contacts with police, dropping from 951 since 2014 to two after being housed.

“This is where the disconnect is when it comes to the community understanding what it takes to house those in need,” said Mike Jordan, the District 2 representative on Santa Barbara City Council.

“You can’t just put people in a home. There is trust to be earned on both ends.”

Jordan’s district was the impetus to a current 120-day clean-up project impacting the homeless, with encampments around the city being cleared out, with a room at the Rose Garden Inn being offered. The invitation is inclusive of any treatment — mental or physical — that might be needed.

It came on the heels of May’s Loma Fire, where the damage on TV Hill was limited to nine acres — with officials indicating that it could have been much worse if the wind had shifted directions.

“We had to look at everything, what we could do to prevent fires like that from happening again,” Jordan said. “The clean-up was necessary, and it also gave us a chance to start the re-housing process with dozens of willing folks.”

At a cost of $1.6 million, the clean-up raised eyebrows and a chorus of complaints from the community.

“I hear that people want the homeless gone all the time, but when we do something about it, we are asked why we are spending that type of money on homelessness,” said Meagan Harmon, the District 6 representative on Santa Barbara City Council. “To create change, it costs money.”

Jordan went a step further — this moment isn’t defined by a dollar figure, but instead in the investment in a process expected to produce significant progress.

“They predict we’re going to see 10s of percentages of a gain in success of people staying, not walking away, and moving on to the next step (of attaining permanent housing),” Jordan said.

Yet, there is a simple but complex question still to be answered:

What happens on Day 121?

Quick Fix vs. Sustainability

With an estimated 1,300 homeless people in Santa Barbara County, renting rooms at one hotel for just under four months isn’t the “silver bullet,” as Harmon calls it.

But the initial response to the opportunity has given both local politicians and outreach agencies some much-needed hope. Nearly 20 people took the city up on the offer on the first day, while 39 have taken advantage since the program kicked off.

“Having a safe door to live behind, with your own bathroom, that’s a big deal,” said Jeff Shaffer, the director of initiatives at the Santa Barbara Alliance for Community Transformation (SBACT), an organization that is receiving praise for its “middle-man” role in organizing outreach groups to create a unified effort.

“The relationships that were already developed with people from those encampments created a chemistry that is allowing this pilot to be successful. That rapport they’ve established that helped these people choose a hotel room over the streets, I cannot over highlight how difficult it is to do that kind of outreach. It’s quite a heavy lift.”

So, now the question is: How does the county or city of Santa Barbara replicate this success? What does sustainability look like?

Shaffer, Jordan, and Harmon all pointed to a county-led project set to break ground on Garden Street that is a showcase for what permanency can look like — in Santa Barbara and elsewhere.

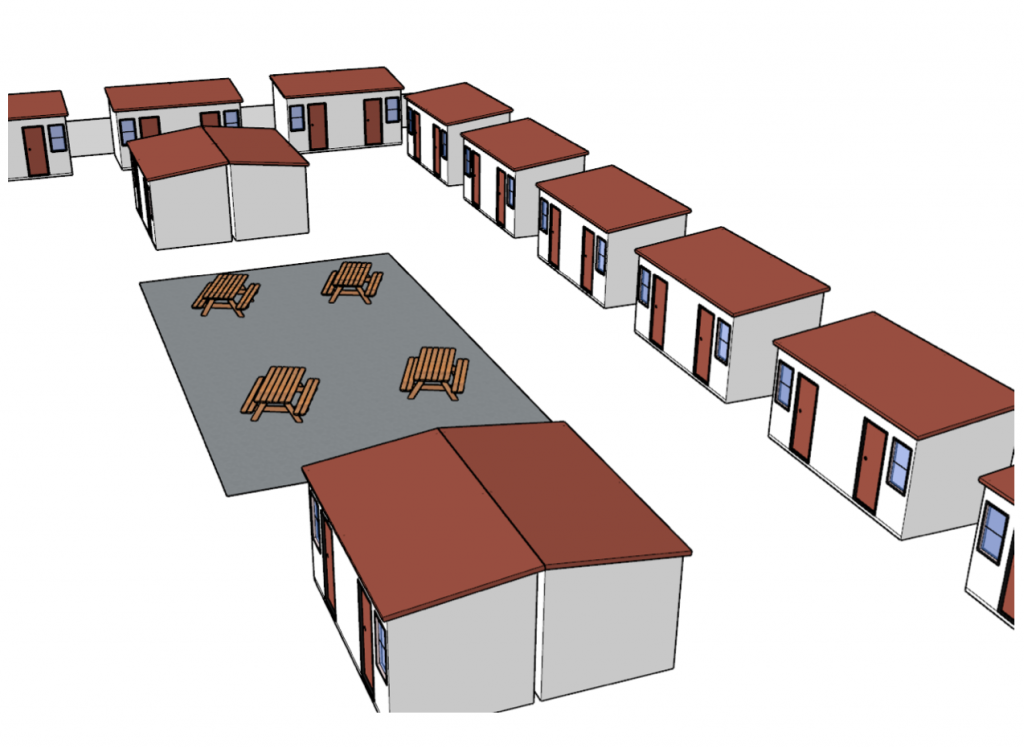

Dignity Moves, a private nonprofit that believes “our streets cannot be the waiting room” to interim supportive housing, will be building a homeless village of up to 35 tiny, prefabricated housing units on government-owned property, which will be ready for use as early as this fall.

Don’t worry — the aesthetics will fit right in to Santa Barbara’s architectural motif.

With the prefabrication, the village will come at a fraction of the cost of normal construction.

“If they’re successful, that means there’s going to be a lot more people in bridge housing being prepared for housing — as we develop more housing opportunities,” Shaffer said. “That’s a win-win for everyone.”

For Das Williams, Santa Barbara County’s First District Supervisor, long-term solutions such as the Dignity Project are paramount, as he has been outspoken about the need for permanent supportive housing, taking temporary fixes and making them long-standing — even if the price tag looks at first a bit higher than expected.

“All I need is parking lots and communities that are willing to have these facilities,” Williams said. “We’ve done a lot of permanent solutions at the county, but we need to do more. We’ll pay going rates for those lots, we just need people to be willing to let us use them.

“We’ve had a hard time finding people ready to take our money.”

Williams isn’t alone in the idea of buying property to aid the homeless, as Jordan says that the success that the current 120-day project is seeing has him wondering if the city shouldn’t also be looking at property to purchase — something they’ve explored in the past.

“It’s definitely on my list, I’m really pushing people hard right now for what happens on Day 121,” Jordan said. “We don’t want folks right back out on the street.”

What’s Already Working?

As short- and long-term options are debated and brought to life, there are also more than a dozen successful local outreach programs which have been aiding the homeless for years.

The New Beginnings Counseling Center services largely center around two main programs: the Safe Parking Program and Supportive Services for Veteran Families Program (SSVF).

“That [SSVF] is a VA-funded and foundation-funded initiative that works to prevent veterans from becoming homeless and/or to help them transition into housing,” said Kristine Schwarz, the organization’s executive director.

New Beginnings operates the program countywide, with about 60% of their clients coming from North County and the remainder being served in Mid and South County. The SSVF program began in 2016 and assists between 250 and 300 veterans each year. New Beginnings served higher than average numbers this past fiscal year, with the SSVF assisting 372 individuals, with 87 of them housed and graduated from the program. Of those served, 151 fell under what is called “light touch case management,” requiring only minimal assistance, with the others being provided more long-term support.

The SPP has expanded over the past couple of years, with HUD indicating that people who are the most vulnerable should be prioritized. This allowed the organization to focus on overnight shelter for those who live in their vehicle, something it has done in both the South County and soon in Lompoc.

“We also work during the day to provide case management, housing navigation, and housing retention case management to help people find housing and to remain in their housing,” Schwarz explained.

The program currently offers 156 parking spots spread between 26 parking lots. In the last year, the Safe Parking Program has served 464 people and helped house 85. The program has been incredibly successful with it being studied and replicated by other organizations and cities. Between the two programs, New Beginnings has contributed nearly $1.25 million in direct financial support this last year.

The transition into permanent housing takes a concerted and multi-pronged effort.

“There are multiple components. Community agencies not only have to work with each other, but we need to work with landlords and property managers to transition people in the house,” Schwarz said.

New Beginnings coordinates with these different members to ensure that not just the tenant but everyone involved has a good understanding of expectations.

“There are many people who have lost their housing for many different reasons and are working with property managers and landlords to forgive a history of insufficient income, or maybe an eviction or bad debt, especially due to COVID and job loss,” Schwarz said.

“It is essential to that one component where we all work together, right?”

Over the past 18 months or so of the pandemic, New Beginnings and many of the organizations had to adapt their programs and experiment with new techniques, such as the motel room rentals. The ability to place program participants in motel rooms allowed them a temporary spot where New Beginnings could further assist them.

This period also provided some important lessons for the organization.

“Well, I think we learned what community resources we need to shore up, in terms of how to respond to any future similar issues,” Schwarz said.

Schwarz sees the issue of homelessness as not just something to be solved by the individual it affects, but rather as part of a larger communal conversation.

“The collective health and safety of our community is at issue here. Everybody has had a really difficult time in the last year and half in a different way,” Schwarz concludes. “One of the consequences of COVID is that homelessness has increased, and mental illness has been exacerbated, and people’s coping mechanisms have been diminished. So, either we all work together to muddle our way through this — or we’re not going to see positive outcomes for any of us.”

Finding a PATH

People Assisting The Homeless, or PATH, has been around the proverbial block, established in the 1980s and having a front-row seat to witness plan after plan from the area’s government bodies either fail or be pushed aside over time.

As one of the largest nonprofit organizations in California helping individuals, veterans, and families obtain permanent housing, PATH has found its own, well, path.

“We work on the housing-first model that most of the agencies work on. That basically, if you don’t have a solid ground, then how can you make these life-changing decisions and get into your own home?” said John Bowlin, PATH’s director of philanthropy and community affairs.

“There’s many tiers to how to solve homelessness, but I think the biggest one is more services. So that means more funding, whether it is public or private funding, so we can help serve more individuals that are experiencing homelessness.”

And while fiscal funding is always ideal, Bowlin also admits that donations can come in many different forms, even down to household items such as hygiene kits — allowing PATH to spruce up a home as it helps an individual or family move into a new house.

The organization is much more than just finding housing, as it also operates the PATH Cooks Program, which makes about 300 meals per day.

The volunteers that help this program function also get a first-hand look at how case workers aid the families in need.

“Our volunteers always learn while they’re here that there is not just one solution to getting someone into permanent supportive housing,” Bowlin said. “It takes our case management sometimes a lot of different tries and a lot of different methods [in order to get] someone housed.”

Bowlin also cautions volunteers about making assumptions about why someone might be homeless and cautions that conclusions can quite often be wrong.

“There’s many layers to why someone might be experiencing homelessness. It is not just one thing. Individuals are either working through some trauma, or something that has led them to being homeless,” Bowlin said. “We hope that this is just a blip on the screen to them. When you put a label on someone, that kind of puts them in a box.”

PATH is also active with the city’s 120-day cleanup, with its Step Up Program aiding in tackling excess trash in a specific neighborhood every third Saturday from 9 am to noon.

“We’re just trying to build that program more and more because we think it’s very important to really get out there and make sure that we help be a part of the solution to some of the trash that we’ve been seeing in our neighborhood lately,” Bowlin said.

A Matter of Community Will

Both Das Williams and Mike Jordan pointed to the concept of a trio of “wills” that need to align for Santa Barbara to move forward with any plan, much less one as polarizing as strategies for dealing with homelessness.

Those “wills” come in the form of financial, political, and community.

As the self-admitted “man on the fence” with most issues, Jordan says that his cup has turned from half-empty to half-full when it comes to combating homelessness, mostly due to the work of both the city staff and organizations such as SBACT.

“I’ve watched this for forever it seems, where everybody was just kind of doing what they wanted to, no one was herding the cats and giving us focus and direction,” Jordan said. “And that has significantly changed recently. I have hope.”

And while Santa Barbara City Council has plenty of distractions nowadays, both Jordan and Meagan Harmon believe that the political alignment on how to move forward is on solid ground.

“I have to believe that we can find solutions,” Harmon said. “And I feel like we are.”

Williams even extended his hand across the aisle, offering kudos to city council as it braves criticism for putting forth a plan.

“Santa Barbara should feel very lucky to have a solutions-oriented council,” Williams said. “Other places, sometimes we have to create solutions over the objection of a city council. Here, they are creating solutions in partnership with others.”

Williams says it is also a fiscally responsible time to set up solutions that keep the South Coast ahead of the curve when it comes to serving the unhoused, pointing to both the city and county making significant investments in infrastructure.

“The money is there, more than ever before,” said Williams, who also pointed to the county utilizing hotels over the past 15 months to aid the homeless during the pandemic.

But it’s the community will that continues to be an obstacle, with neighborhoods wanting solutions, but not wanting them to impact their portion of the community, according to all three politicians.

And, in that, the political alignment and excess funds can ultimately mean very little. In many ways, it’s an all-or-nothing situation.

“A lot of the people who are complaining the most about homelessness are also complaining loudly about the solutions,” Williams said. “I don’t know how the city’s supposed to win on that.”

Joe might have provided that blueprint: time, patience, and, most importantly, trust.

You must be logged in to post a comment.